To review: A voter in Montana gets 31 times the electoral bang for their presidential vote than a voter in New York. A voter in Wyoming has 70 times the representation in the Senate as a voter in California, while citizens in Puerto Rico or Washington D.C. have none. The Republican Senate majority that recently confirmed Amy Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court, was elected by 14 million fewer votes than the 47 senators who voted against her confirmation.

Yet politicians and pundits regularly pronounce the United States a "democracy," as if that designation is self-evident and incontrovertible. Textbooks and mainstream civics curricula make the same mistake, treating democracy as a fact rather than an enduring struggle -- in which our students can play a critical role.

The standard iteration of "civics" in schools stipulates the brilliance of the framers, the democratic nature of the U.S. system, the infallibility of the Constitution (it was built to be amended!), so that our institutions seem outside of history and beyond politics. As the Koch Brothers-funded Bill of Rights (BRI) Institute states,

The founding documents are the true primary sources of America. Writings such as the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, the Bill of Rights, and others written from 1764 to 1791, showcase the philosophical, traditional, and political foundations on which our nation was built and that continue to shape our free society.

"Our free society." One danger of a curriculum that declares the United States "free" is that it casts all U.S. institutions, by definition, as also free. The district-adopted textbook I was assigned last year in my Portland, Oregon, suburb, America Through the Lens (National Geographic, 2019), says about the 2016 presidential election, "...Trump won a narrow majority of voters in a number of swing states, or states where the election might go to either party. Even though almost 3 million more Americans cast their votes for Clinton, Trump won the electoral vote 306 to 232." Since freedom is assumed, this textbook sees no need to offer any elaboration of a system in which "swing states" are decisive, and in which the person selected by the majority of voters does not win the presidency.

Perhaps the editors of America Through the Lens assume students have read a previous section of the text on the Electoral College? No. Paging back to the chapter on the Constitution, one finds only this anemic paragraph:

But how should the president be chosen? Some delegates thought the president should be directly elected by the voters. Others wanted Congress or the state legislatures to make the choice. The delegates finally arrived at a solution: an electoral college made up of electors from each state would cast official votes for the president and vice president. The number of electors from each state would be the same as the state's number of representatives in Congress, and each state could decide how to choose its electors.

Students deserve an explanation for the origins of the Electoral College. Instead, the textbook offers mere description, dry as dust. We learn that the Electoral College emerged from a disagreement among delegates, but nothing about the actual substance of that disagreement or the interests at stake. Shouldn't the authors explain to students why our founders rejected direct election of the president by the people, the most democratic option? With no sense of the problem, textbook writers assure students that the Electoral College was a "solution" and send them on their merry way.

But for whom was the Electoral College a solution? Many of the 55 White men at the Constitutional Convention worried about giving too much power to the people. Alexander Hamilton said the masses were prone to passion and might use their vote unwisely. Of course, both passion and wisdom are highly subjective terms. James Madison listed the "wicked schemes" inflaming the people to act so unwisely: "A rage for paper money, for an abolition of debts, for an equal division of property. . ." Madison called voters advancing their own economic interests wicked, but referred to his brethren -- insulating their own wealth and power in Philadelphia -- as "enlightened statesmen." The Electoral College was a "solution" to the bankers and plantation owners in 1787 but looked like exclusion if you were a poor indebted veteran in western Massachusetts, an enslaved person in Virginia, or a Hitchiti person fleeing land-thieving White settlers in Georgia.

Soldiers fire on protesters during Shays' Rebellion. Led by Daniel Shays, a group of poor farmers and Revolutionary War veterans attempted to shut down Massachusetts courts in protest against debt collections against veterans and the heavy tax burden borne by the colony's farmers.

Madison expressed another set of concerns about the direct election of the president. He pointed out that a popular vote would deprive the White South of "influence in the election on the score of the Negroes." He was, of course, referring to the 40 percent of the southern U.S. population made up of enslaved people. Since the men at the Constitutional Convention had already adopted the Three-Fifths Compromise, establishing that enslaved people would bolster enslavers' representation in Congress, the Electoral College was a "solution" because it meant the humans they violently exploited would inflate their influence in presidential elections too.

When my textbook matter-of-factly declares that the Electoral College was a "solution," but makes no mention of the elite and white supremacist interests for whom that was true, nor the exploited and disenfranchised peoples for whom it was a disaster, it does not educate students, but lies to them. The very same textbooks that paint the Three-Fifths Compromise as a shameful relic of slavery, treat the Electoral College as an unremarkable feature of our system, as if they were not borne of the same white supremacist original sin.

This feigned neutrality covers up the classist and racist origins of our institutions. It is not only bad history but signals to students in 2020, "Nothing to see here." The mock elections and legislative simulations common in U.S. civics classrooms encourage students to investigate the swirl of issues inside the container of U.S. "democracy," but rarely the container itself. Students are commanded to vote, but not to judge the fundamental questions of governance not on the ballot -- like the legitimacy of an electoral college devised by enslavers. What if our civics invited students not just to become occupants of an already-built U.S. government, but engineers and architects able to redesign, reframe, and rebuild the whole structure? What if our civics repurposed the word "framer" to mean all of us today -- including our students?

One way to cultivate this activist sensibility in our students is to offer them a curriculum rich with an alternative pantheon of "framers" and "founding parents" in the ongoing struggle for democracy. Central to this project is the rejection of the singular, miraculous, and exceptional founding peddled by the Bill of Rights Institute and others. As Eric Foner's newest book, The Second Founding -- about the Reconstruction Amendments that finally made multiracial democracy possible -- suggests, building freedom is a work in progress.

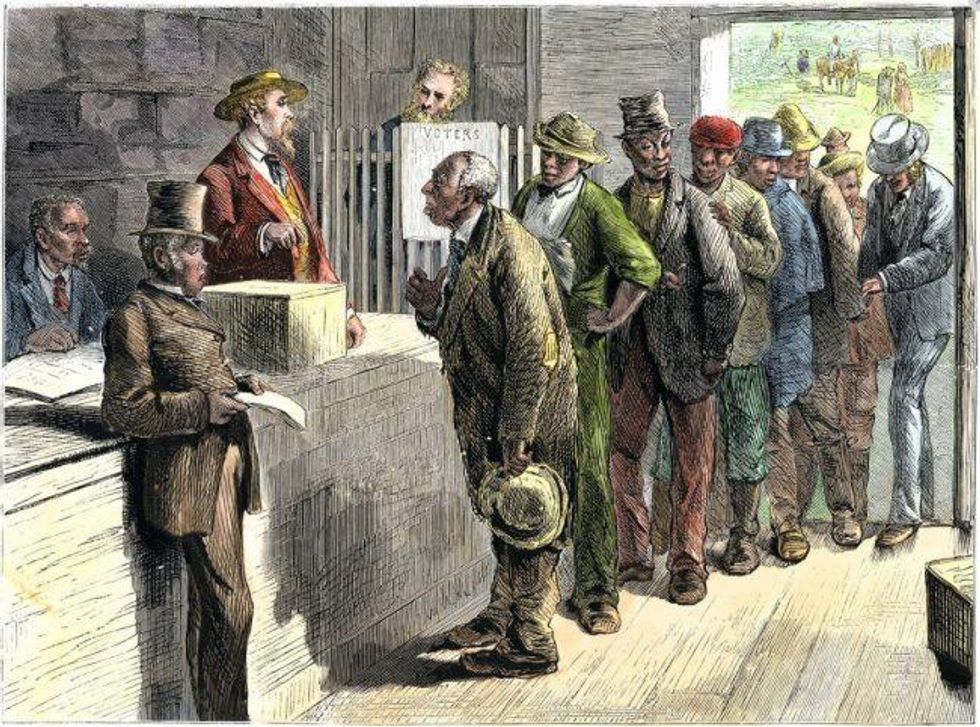

Similarly, many scholars and activists, notably the Rev. William Barber II, have embraced the idea of a multiplicity of Reconstructions: the first Reconstruction, following the Civil War in which freedpeople and their allies reimagined citizenship, social relationships, and politics; the second Reconstruction in the 20th century, when Black activists and their allies dismantled 100 years of Jim Crow, championed and popularized "one person, one vote," and transformed U.S. law and society; and the third Reconstruction, happening now, exemplified by Black Lives Matter, the Dream Defenders, United We Dream, and others to address the ongoing manifestations of systemic racism in everything from housing to immigration, policing to education. In this telling, the United States has been constructed by many framers, not just those White elites in Philadelphia, but also the millions of unsung heroes who have never stopped seeking to transform the United States and the meaning of freedom.

Angela Davis writes that "freedom is a constant struggle." When, for example, we teach students about the fight for the 15th Amendment, alongside the movement 100 years later for the Voting Rights Act, alongside the efforts now to combat voter suppression, we not only provide evidence of Davis's words, but invite students into that struggle. By rejecting both the textbook's boring and evasive approach to our anti-democratic institutions, and BRI's glorification of a U.S. founding that meant -- and continues to mean -- oppression for so many, we affirm our students' reality and provide models of activism through which they might reimagine and revise it.

On November 2, 2020, one day before the general election that would deny him a second term, Donald J. Trump issued an executive order establishing the 1776 Commission. The commission's mandate? A "restoration of American education" to emphasize the "clear historical record of an exceptional Nation dedicated to the ideas and ideals of its founding." President Trump has been defeated, but this commitment to institutionalize the teaching of American exceptionalism has not. We educators must fight for a curriculum that teaches our students facts not fables. The United States has never been a democracy, defined by freedom and equality for all. But nor has there ever been a time when people did not struggle toward a democratic future, dreaming of freedom, risking life and limb to make those dreams manifest, and creating a more just society along the way. Let's teach civics and history that affirms for our students there is nothing sacrosanct in the political and economic status quo, that freedom fighters, past and present, are founders too, and we all have a right to be framers -- to redesign this structurally unsound house to better shelter our lives, safety, comfort, and full humanity.