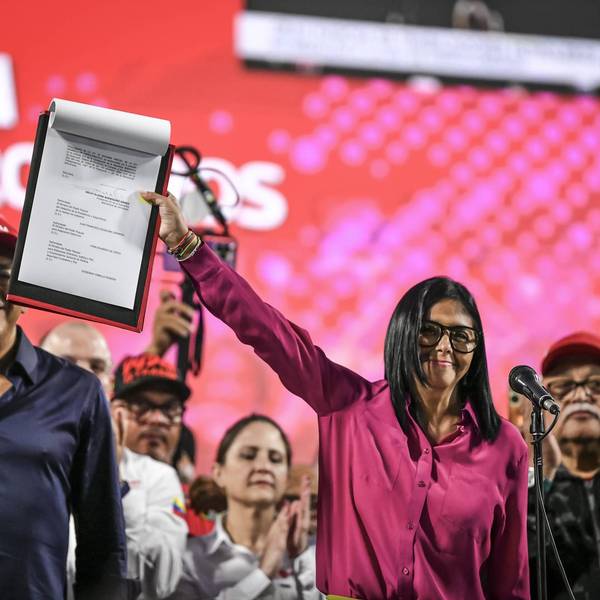

Supporters of Venezuela's President Nicolas Maduro gather in the streets of Caracas on January 3, 2026, after US forces captured him.

Trump Is Just the Latest Strongman to Think He Can Control Venezuela

Again and again, external actors arrive convinced that this time, through capital, force, or expertise, they have finally grasped what Venezuela is and what it needs. The confidence never lasts.

When US forces carried out a large-scale military operation in Caracas on January 3, 2026—capturing President Nicolás Maduro and transporting him to New York to face US indictments—Washington framed the moment as resolution. President Donald Trump declared Venezuela’s long crisis effectively over, announcing that the United States would “run” the country for a period of time and openly discussing the reinstallation of US oil interests. The language was casual, almost improvisational, as if Venezuela were an unruly subsidiary finally brought to heel.

What the operation revealed, however, was not strategic clarity but a familiar blindness. Once again, US power moved decisively while understanding lagged far behind. Leadership was removed, headlines were captured, yet the deeper structures shaping Venezuelan life—its history of extraction, its social networks, its hard-earned skepticism toward imposed authority—remained untouched. The episode fit neatly into a long pattern: Outsiders mistaking control for comprehension.

For more than five centuries, Venezuela has attracted this kind of attention. It has been treated as a resource cache, a geopolitical puzzle, a cautionary tale, or a problem to be solved. Rarely has it been approached as a society with its own internal logic. Again and again, external actors arrive convinced that this time, through capital, force, or expertise, they have finally grasped what Venezuela is and what it needs. The confidence never lasts.

The misreading begins early. When Alonso de Ojeda and Amerigo Vespucci reached the northern coast in 1499 and named it Veneziola, they imposed a European metaphor on a place already dense with meaning. Indigenous societies—the Timoto-Cuica in the Andes, Carib and Arawak peoples along the coast—had built complex agricultural systems, trade routes, and ecological knowledge. Spanish conquest dismantled much of this world, extracting pearls, gold, and cacao while concentrating power in Caracas, a city whose monumental architecture masked the fragility beneath it.

Venezuela has been misread repeatedly. Not because it is unknowable, but because powerful outsiders rarely bother to know it on its own terms.

Colonial Venezuela was never cohesive. Authority flowed downward; legitimacy never followed. The German Welser banking house, granted control of the territory in the 16th century, pursued gold through enslavement and violence. Later, the Guipuzcoan Company monopolized trade, choking local economic life. Periodic uprisings were crushed rather than resolved. The lesson repeated itself quietly but insistently: Wealth could be extracted, order imposed temporarily, but social trust could not be engineered from afar.

Independence did not resolve these tensions. 19th century unfolded through fragmentation, regionalism, and civil war. Simón Bolívar understood Venezuela better than most foreign admirers or critics since, yet even he struggled to translate military success into durable political unity. The Federal War left the country devastated and more unequal, reinforcing a pattern in which power was centralized while social cohesion remained elusive. European creditors and early oil prospectors took note, circling patiently.

Oil altered Venezuela’s position in the world but not its underlying dynamics. In the early 20th century, Juan Vicente Gómez offered foreign companies stability and access in exchange for political backing. Later, Marcos Pérez Jiménez presented a gleaming vision of modernization—highways, towers, civic monuments—that impressed visiting dignitaries. The spectacle worked. Venezuela appeared governable, even exemplary. Yet outside the frame, inequality hardened and participation narrowed. Development was visible; legitimacy was thin.

By the time the bolívar collapsed on Black Friday in 1983, the illusion was difficult to sustain. An economy tethered to oil rents proved dangerously exposed to global shocks, while political institutions remained distant from everyday life. The Caracazo riots of 1989 were not a sudden breakdown but a release, an eruption from a society that had absorbed decades of exclusion. International observers described chaos. Venezuelans recognized continuity.

Hugo Chávez entered this landscape not as a rupture but as a condensation of long-simmering forces. His rise drew on popular frustration with a system that had promised stability and delivered precarity. The brief 2002 coup against him, quietly welcomed in Washington, collapsed almost immediately, undone by mass mobilization. Power changed hands; legitimacy reasserted itself. Chávez’s social programs produced real gains while deepening reliance on oil, leaving unresolved the same vulnerability that had defined Venezuelan political economy for a century.

After Chávez’s death, Nicolás Maduro governed a system already under strain. Falling oil prices, hyperinflation, protest cycles, mass migration, and partial dollarization followed. External pressure mounted, sanctions, recognition battles, diplomatic theater, often treating Venezuela less as a society than as a message. Leadership was personalized; history flattened.

The capture of Maduro followed this script. It was decisive, dramatic, and legible to a US political culture that favors clear villains and clean endings. What it did not do was engage the complexity of Venezuelan life: the informal economies that keep neighborhoods fed, the communal networks that substitute for absent institutions, the cultural memory shaped by centuries of extraction and resistance. These dynamics do not disappear when a president boards a plane.

Venezuelan resilience rarely makes headlines because it lacks spectacle. It is found in Indigenous land stewardship, Afro-Venezuelan cultural traditions, cooperative food systems, remittance networks, and everyday improvisation. Migration, so often framed solely as collapse, has also become a form of continuity, extending social ties across borders rather than severing them.

Oil still looms over everything. The 1970s boom, including Saudi-Venezuelan cooperation, promised autonomy through abundance and delivered deeper dependence instead. Resource wealth invited intervention and centralization while postponing harder questions about participation and governance. The pattern has proven remarkably durable.

Venezuela’s history does not yield easily to slogans or interventions. It resists tidy moral arcs and quick fixes. Again and again, external actors—most recently the Trump administration—have approached the country as if force, markets, or managerial confidence could substitute for understanding. Each time, they discover too late that Venezuela is not an abstraction but a living society shaped by long memory and adaptive survival.

Venezuela has been misread repeatedly. Not because it is unknowable, but because powerful outsiders rarely bother to know it on its own terms. And so the cycle continues: decisive action, confident declarations, and, beneath them all, a society that endures—complex, unfinished, and stubbornly beyond control.An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

When US forces carried out a large-scale military operation in Caracas on January 3, 2026—capturing President Nicolás Maduro and transporting him to New York to face US indictments—Washington framed the moment as resolution. President Donald Trump declared Venezuela’s long crisis effectively over, announcing that the United States would “run” the country for a period of time and openly discussing the reinstallation of US oil interests. The language was casual, almost improvisational, as if Venezuela were an unruly subsidiary finally brought to heel.

What the operation revealed, however, was not strategic clarity but a familiar blindness. Once again, US power moved decisively while understanding lagged far behind. Leadership was removed, headlines were captured, yet the deeper structures shaping Venezuelan life—its history of extraction, its social networks, its hard-earned skepticism toward imposed authority—remained untouched. The episode fit neatly into a long pattern: Outsiders mistaking control for comprehension.

For more than five centuries, Venezuela has attracted this kind of attention. It has been treated as a resource cache, a geopolitical puzzle, a cautionary tale, or a problem to be solved. Rarely has it been approached as a society with its own internal logic. Again and again, external actors arrive convinced that this time, through capital, force, or expertise, they have finally grasped what Venezuela is and what it needs. The confidence never lasts.

The misreading begins early. When Alonso de Ojeda and Amerigo Vespucci reached the northern coast in 1499 and named it Veneziola, they imposed a European metaphor on a place already dense with meaning. Indigenous societies—the Timoto-Cuica in the Andes, Carib and Arawak peoples along the coast—had built complex agricultural systems, trade routes, and ecological knowledge. Spanish conquest dismantled much of this world, extracting pearls, gold, and cacao while concentrating power in Caracas, a city whose monumental architecture masked the fragility beneath it.

Venezuela has been misread repeatedly. Not because it is unknowable, but because powerful outsiders rarely bother to know it on its own terms.

Colonial Venezuela was never cohesive. Authority flowed downward; legitimacy never followed. The German Welser banking house, granted control of the territory in the 16th century, pursued gold through enslavement and violence. Later, the Guipuzcoan Company monopolized trade, choking local economic life. Periodic uprisings were crushed rather than resolved. The lesson repeated itself quietly but insistently: Wealth could be extracted, order imposed temporarily, but social trust could not be engineered from afar.

Independence did not resolve these tensions. 19th century unfolded through fragmentation, regionalism, and civil war. Simón Bolívar understood Venezuela better than most foreign admirers or critics since, yet even he struggled to translate military success into durable political unity. The Federal War left the country devastated and more unequal, reinforcing a pattern in which power was centralized while social cohesion remained elusive. European creditors and early oil prospectors took note, circling patiently.

Oil altered Venezuela’s position in the world but not its underlying dynamics. In the early 20th century, Juan Vicente Gómez offered foreign companies stability and access in exchange for political backing. Later, Marcos Pérez Jiménez presented a gleaming vision of modernization—highways, towers, civic monuments—that impressed visiting dignitaries. The spectacle worked. Venezuela appeared governable, even exemplary. Yet outside the frame, inequality hardened and participation narrowed. Development was visible; legitimacy was thin.

By the time the bolívar collapsed on Black Friday in 1983, the illusion was difficult to sustain. An economy tethered to oil rents proved dangerously exposed to global shocks, while political institutions remained distant from everyday life. The Caracazo riots of 1989 were not a sudden breakdown but a release, an eruption from a society that had absorbed decades of exclusion. International observers described chaos. Venezuelans recognized continuity.

Hugo Chávez entered this landscape not as a rupture but as a condensation of long-simmering forces. His rise drew on popular frustration with a system that had promised stability and delivered precarity. The brief 2002 coup against him, quietly welcomed in Washington, collapsed almost immediately, undone by mass mobilization. Power changed hands; legitimacy reasserted itself. Chávez’s social programs produced real gains while deepening reliance on oil, leaving unresolved the same vulnerability that had defined Venezuelan political economy for a century.

After Chávez’s death, Nicolás Maduro governed a system already under strain. Falling oil prices, hyperinflation, protest cycles, mass migration, and partial dollarization followed. External pressure mounted, sanctions, recognition battles, diplomatic theater, often treating Venezuela less as a society than as a message. Leadership was personalized; history flattened.

The capture of Maduro followed this script. It was decisive, dramatic, and legible to a US political culture that favors clear villains and clean endings. What it did not do was engage the complexity of Venezuelan life: the informal economies that keep neighborhoods fed, the communal networks that substitute for absent institutions, the cultural memory shaped by centuries of extraction and resistance. These dynamics do not disappear when a president boards a plane.

Venezuelan resilience rarely makes headlines because it lacks spectacle. It is found in Indigenous land stewardship, Afro-Venezuelan cultural traditions, cooperative food systems, remittance networks, and everyday improvisation. Migration, so often framed solely as collapse, has also become a form of continuity, extending social ties across borders rather than severing them.

Oil still looms over everything. The 1970s boom, including Saudi-Venezuelan cooperation, promised autonomy through abundance and delivered deeper dependence instead. Resource wealth invited intervention and centralization while postponing harder questions about participation and governance. The pattern has proven remarkably durable.

Venezuela’s history does not yield easily to slogans or interventions. It resists tidy moral arcs and quick fixes. Again and again, external actors—most recently the Trump administration—have approached the country as if force, markets, or managerial confidence could substitute for understanding. Each time, they discover too late that Venezuela is not an abstraction but a living society shaped by long memory and adaptive survival.

Venezuela has been misread repeatedly. Not because it is unknowable, but because powerful outsiders rarely bother to know it on its own terms. And so the cycle continues: decisive action, confident declarations, and, beneath them all, a society that endures—complex, unfinished, and stubbornly beyond control.- After Venezuela Assault, Trump and Rubio Warn Cuba, Mexico, and Colombia Could Be Next ›

- 'We Are Going to Run the Country,' Trump Says of Venezuela After Maduro Abduction ›

- What Is Trump's True Endgame in Venezuela? ›

- Trump Claims Venezuelan Airspace Is Closed in Latest Illegal, 'Dangerous Escalation' ›

- Defying Trump, Venezuela VP Says 'We Will Never Again Be a Colony of Any Empire' ›

- 'The Actions of a Rogue State': US Lawmakers Demand Emergency Vote to Stop Trump War on Venezuela ›

When US forces carried out a large-scale military operation in Caracas on January 3, 2026—capturing President Nicolás Maduro and transporting him to New York to face US indictments—Washington framed the moment as resolution. President Donald Trump declared Venezuela’s long crisis effectively over, announcing that the United States would “run” the country for a period of time and openly discussing the reinstallation of US oil interests. The language was casual, almost improvisational, as if Venezuela were an unruly subsidiary finally brought to heel.

What the operation revealed, however, was not strategic clarity but a familiar blindness. Once again, US power moved decisively while understanding lagged far behind. Leadership was removed, headlines were captured, yet the deeper structures shaping Venezuelan life—its history of extraction, its social networks, its hard-earned skepticism toward imposed authority—remained untouched. The episode fit neatly into a long pattern: Outsiders mistaking control for comprehension.

For more than five centuries, Venezuela has attracted this kind of attention. It has been treated as a resource cache, a geopolitical puzzle, a cautionary tale, or a problem to be solved. Rarely has it been approached as a society with its own internal logic. Again and again, external actors arrive convinced that this time, through capital, force, or expertise, they have finally grasped what Venezuela is and what it needs. The confidence never lasts.

The misreading begins early. When Alonso de Ojeda and Amerigo Vespucci reached the northern coast in 1499 and named it Veneziola, they imposed a European metaphor on a place already dense with meaning. Indigenous societies—the Timoto-Cuica in the Andes, Carib and Arawak peoples along the coast—had built complex agricultural systems, trade routes, and ecological knowledge. Spanish conquest dismantled much of this world, extracting pearls, gold, and cacao while concentrating power in Caracas, a city whose monumental architecture masked the fragility beneath it.

Venezuela has been misread repeatedly. Not because it is unknowable, but because powerful outsiders rarely bother to know it on its own terms.

Colonial Venezuela was never cohesive. Authority flowed downward; legitimacy never followed. The German Welser banking house, granted control of the territory in the 16th century, pursued gold through enslavement and violence. Later, the Guipuzcoan Company monopolized trade, choking local economic life. Periodic uprisings were crushed rather than resolved. The lesson repeated itself quietly but insistently: Wealth could be extracted, order imposed temporarily, but social trust could not be engineered from afar.

Independence did not resolve these tensions. 19th century unfolded through fragmentation, regionalism, and civil war. Simón Bolívar understood Venezuela better than most foreign admirers or critics since, yet even he struggled to translate military success into durable political unity. The Federal War left the country devastated and more unequal, reinforcing a pattern in which power was centralized while social cohesion remained elusive. European creditors and early oil prospectors took note, circling patiently.

Oil altered Venezuela’s position in the world but not its underlying dynamics. In the early 20th century, Juan Vicente Gómez offered foreign companies stability and access in exchange for political backing. Later, Marcos Pérez Jiménez presented a gleaming vision of modernization—highways, towers, civic monuments—that impressed visiting dignitaries. The spectacle worked. Venezuela appeared governable, even exemplary. Yet outside the frame, inequality hardened and participation narrowed. Development was visible; legitimacy was thin.

By the time the bolívar collapsed on Black Friday in 1983, the illusion was difficult to sustain. An economy tethered to oil rents proved dangerously exposed to global shocks, while political institutions remained distant from everyday life. The Caracazo riots of 1989 were not a sudden breakdown but a release, an eruption from a society that had absorbed decades of exclusion. International observers described chaos. Venezuelans recognized continuity.

Hugo Chávez entered this landscape not as a rupture but as a condensation of long-simmering forces. His rise drew on popular frustration with a system that had promised stability and delivered precarity. The brief 2002 coup against him, quietly welcomed in Washington, collapsed almost immediately, undone by mass mobilization. Power changed hands; legitimacy reasserted itself. Chávez’s social programs produced real gains while deepening reliance on oil, leaving unresolved the same vulnerability that had defined Venezuelan political economy for a century.

After Chávez’s death, Nicolás Maduro governed a system already under strain. Falling oil prices, hyperinflation, protest cycles, mass migration, and partial dollarization followed. External pressure mounted, sanctions, recognition battles, diplomatic theater, often treating Venezuela less as a society than as a message. Leadership was personalized; history flattened.

The capture of Maduro followed this script. It was decisive, dramatic, and legible to a US political culture that favors clear villains and clean endings. What it did not do was engage the complexity of Venezuelan life: the informal economies that keep neighborhoods fed, the communal networks that substitute for absent institutions, the cultural memory shaped by centuries of extraction and resistance. These dynamics do not disappear when a president boards a plane.

Venezuelan resilience rarely makes headlines because it lacks spectacle. It is found in Indigenous land stewardship, Afro-Venezuelan cultural traditions, cooperative food systems, remittance networks, and everyday improvisation. Migration, so often framed solely as collapse, has also become a form of continuity, extending social ties across borders rather than severing them.

Oil still looms over everything. The 1970s boom, including Saudi-Venezuelan cooperation, promised autonomy through abundance and delivered deeper dependence instead. Resource wealth invited intervention and centralization while postponing harder questions about participation and governance. The pattern has proven remarkably durable.

Venezuela’s history does not yield easily to slogans or interventions. It resists tidy moral arcs and quick fixes. Again and again, external actors—most recently the Trump administration—have approached the country as if force, markets, or managerial confidence could substitute for understanding. Each time, they discover too late that Venezuela is not an abstraction but a living society shaped by long memory and adaptive survival.

Venezuela has been misread repeatedly. Not because it is unknowable, but because powerful outsiders rarely bother to know it on its own terms. And so the cycle continues: decisive action, confident declarations, and, beneath them all, a society that endures—complex, unfinished, and stubbornly beyond control.- After Venezuela Assault, Trump and Rubio Warn Cuba, Mexico, and Colombia Could Be Next ›

- 'We Are Going to Run the Country,' Trump Says of Venezuela After Maduro Abduction ›

- What Is Trump's True Endgame in Venezuela? ›

- Trump Claims Venezuelan Airspace Is Closed in Latest Illegal, 'Dangerous Escalation' ›

- Defying Trump, Venezuela VP Says 'We Will Never Again Be a Colony of Any Empire' ›

- 'The Actions of a Rogue State': US Lawmakers Demand Emergency Vote to Stop Trump War on Venezuela ›