June, 14 2011, 12:47pm EDT

Forest Service Implements Rules at National Cave Convention in Colorado to Prevent Spread of Bat-killing Disease

Attendees at a national caving convention in Colorado have been granted access to caves in the White River National Forest -- closed since last summer due to the bat-killing epidemic called white-nose syndrome -- but will have to adhere to strict rules to limit the risk of spreading the disease. The U.S. Forest Service is granting an exemption to its ban on cave access in the Rocky Mountain Region and has granted the National Speleological Society a special-use permit that includes strict stipulations on which caves may be visited and what gear used.

GLENWOOD SPRINGS, Colo.

Attendees at a national caving convention in Colorado have been granted access to caves in the White River National Forest -- closed since last summer due to the bat-killing epidemic called white-nose syndrome -- but will have to adhere to strict rules to limit the risk of spreading the disease. The U.S. Forest Service is granting an exemption to its ban on cave access in the Rocky Mountain Region and has granted the National Speleological Society a special-use permit that includes strict stipulations on which caves may be visited and what gear used.

Last summer, the Forest Service issued an emergency cave closure for the region in response to the westward movement of white-nose syndrome, which has already killed more than 1 million bats in North America. Biologists believe that humans, as well as bats, have the ability to spread the fungus associated with the disease.

"White-nose syndrome has already exacted a terrible toll on bats in the eastern United States and put several species at risk of extinction," said Mollie Matteson, conservation advocate at the Center for Biological Diversity. "Stemming the spread of this terrible disease should be a top priority for all government agencies that oversee wildlife or public land that's home to bats. The Forest Service knew cavers would be coming to Colorado for this convention and would want to go into caves, so it has tried to impose the most protective rules possible."

The Forest Service permit allows access to a handful of caves that have very few or no bats. Convention attendees joining cave trips must adhere to strict protocols regarding the gear they use, which must either be decontaminated according to prescribed procedures or have never been previously used for caving. No gear from states or provinces with known white-nose syndrome sites will be allowed at the convention. The Forest Service is requiring post-trip decontamination as well.

"We have been calling for closure of all caves with bats in order to stop the spread of the disease to new regions," said Matteson. "By precluding entry to known bat caves, this rule is close to what we've been asking for and supports the position that bat caves shouldn't be entered. The Bureau of Land Management needs to enact similar measures, and both agencies need to carefully monitor cave entry during the conference to ensure rules are followed."

The caving group has also applied for a permit to visit BLM caves in the Glenwood Springs area. The agency has no cave closures for white-nose syndrome in Colorado, and while it recently issued a proposal for limited, seasonal closures of caves under the jurisdiction of the Colorado River Valley Field Office, there are no requirements currently in place for decontamination or restrictions on gear brought into caves.

In the eastern United States, white-nose syndrome has devastated populations of hibernating bats. Since its discovery in a cave in upstate New York in 2006, the disease has spread to 17 states and four Canadian provinces. The fungus believed to cause white-nose syndrome was also found on bats in Missouri and western Oklahoma in 2010. Scientists believe the epidemic has the potential to affect all two dozen hibernating bat species in the United States, and left unchecked could cause the extinction of one or more species. Earlier this year, a study published in Science estimated that the value of insect-eating bats to agriculture in the United States was $3.7 billion to $53 billion per year.

At the Center for Biological Diversity, we believe that the welfare of human beings is deeply linked to nature — to the existence in our world of a vast diversity of wild animals and plants. Because diversity has intrinsic value, and because its loss impoverishes society, we work to secure a future for all species, great and small, hovering on the brink of extinction. We do so through science, law and creative media, with a focus on protecting the lands, waters and climate that species need to survive.

(520) 623-5252LATEST NEWS

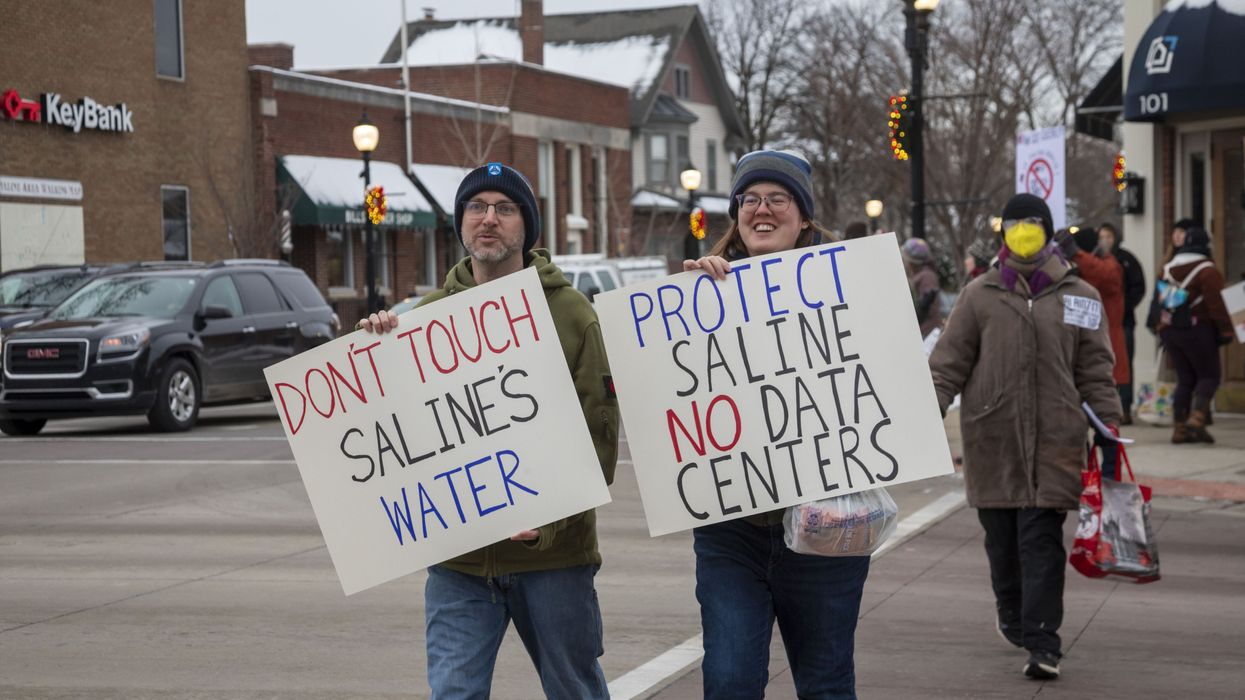

Sanders Champions Those Fighting Back Against Water-Sucking, Energy-Draining, Cost-Boosting Data Centers

Dec 10, 2025

Americans who are resisting the expansion of artificial intelligence data centers in their communities are up against local law enforcement and the Trump administration, which is seeking to compel cities and towns to host the massive facilities without residents' input.

On Wednesday, US Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) urged AI data center opponents to keep up the pressure on local, state, and federal leaders, warning that the rapid expansion of the multi-billion-dollar behemoths in places like northern Virginia, Wisconsin, and Michigan is set to benefit "oligarchs," while working people pay "with higher water and electric bills."

"Americans must fight back against billionaires who put profits over people," said the senator.

In a video posted on the social media platform X, Sanders pointed to two major AI projects—a $165 billion data center being built in Abilene, Texas by OpenAI and Oracle and one being constructed in Louisiana by Meta.

The centers are projected to use as much electricity as 750,000 homes and 1.2 million homes, respectively, and Meta's project will be "the size of Manhattan."

Hundreds gathered in Abilene in October for a "No Kings" protest where one local Democratic political candidate spoke out against "billion-dollar corporations like Oracle" and others "moving into our rural communities."

"They’re exploiting them for all of their resources, and they are creating a surveillance state,” said Riley Rodriguez, a candidate for Texas state Senate District 28.

In Holly Ridge, Lousiana, the construction of the world's largest data center has brought thousands of dump trucks and 18-wheelers driving through town on a daily basis, causing crashes to rise 600% and forcing a local school to shut down its playground due to safety concerns.

And people in communities across the US know the construction of massive data centers are only the beginning of their troubles, as electricity bills have surged this year in areas like northern Virginia, Illinois, and Ohio, which have a high concentration of the facilities.

The centers are also projected to use the same amount of water as 18.5 million homes normally, according to a letter signed by more than 200 environmental justice groups this week.

And in a survey of Pennsylvanians last week, Emerson College found 55% of respondents believed the expansion of AI will decrease the number of jobs available in their current industry. Sanders released an analysis in October showing that corporations including Amazon, Walmart, and UnitedHealth Group are already openly planning to slash jobs by shifting operations to AI.

In his video on Wednesday, Sanders applauded residents who have spoken out against the encroachment of Big Tech firms in their towns and cities.

"In community after community, Americans are fighting back against the data centers being built by some of the largest and most powerful corporations in the world," said Sanders. "They are opposing the destruction of their local environment, soaring electric bills, and the diversion of scarce water supplies."

Keep ReadingShow Less

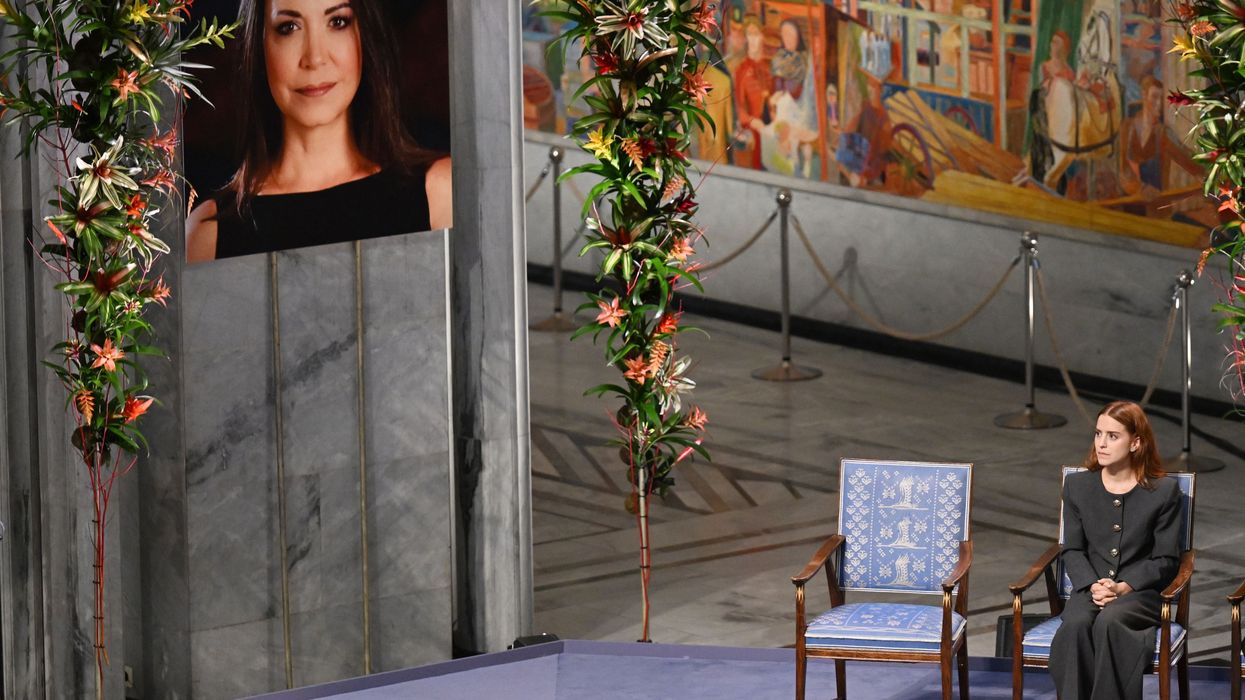

Protest in Oslo Denounces Nobel Peace Prize for Right-Wing Machado

"No peace prize for warmongers," said one of the banners displayed by demonstrators, who derided Machado's support for President Donald Trump's regime change push in Venezuela.

Dec 10, 2025

As President Donald Trump issued new threats of a possible ground invasion in Venezuela, protesters gathered outside the Norwegian Nobel Institute in Oslo on Tuesday to protest the awarding of the prestigious peace prize to right-wing opposition leader Maria Corina Machado, whom they described as an ally to US regime change efforts.

“This year’s Nobel Prize winner has not distanced herself from the interventions and the attacks we are seeing in the Caribbean, and we are stating that this clearly breaks with Alfred Nobel’s will," said Lina Alvarez Reyes, the information adviser for the Norwegian Solidarity Committee for Latin America, one of the groups that organized the protests.

Machado's daughter delivered a speech accepting the award on her behalf on Wednesday. The 58-year-old engineer was unable to attend the ceremony in person due to a decade-long travel ban imposed by Venezuelan authorities under the government of President Nicolás Maduro.

Via her daughter, Machado said that receiving the award "reminds the world that democracy is essential to peace... And more than anything, what we Venezuelans can offer the world is the lesson forged through this long and difficult journey: that to have a democracy, we must be willing to fight for freedom."

But the protesters who gathered outside the previous day argue that Machado—who dedicated her acceptance of the award in part to Trump and has reportedly worked behind the scenes to pressure Washington to ramp up military and financial pressure on Venezuela—is not a beacon of democracy, but a tool of imperialist control.

As Venezuelan-American activist Michelle Ellner wrote in Common Dreams in October after Machado received the award:

She worked hand in hand with Washington to justify regime change, using her platform to demand foreign military intervention to “liberate” Venezuela through force.

She cheered on Donald Trump’s threats of invasion and his naval deployments in the Caribbean, a show of force that risks igniting regional war under the pretext of “combating narco-trafficking.” While Trump sent warships and froze assets, Machado stood ready to serve as his local proxy, promising to deliver Venezuela’s sovereignty on a silver platter.

She pushed for the US sanctions that strangled the economy, knowing exactly who would pay the price: the poor, the sick, the working class.

The protesters outside the Nobel Institute on Tuesday felt similarly: "No peace prize for warmongers," read one banner. "US hands off Latin America," read another.

The protest came on the same day Trump told reporters that an attack on the mainland of Venezuela was coming soon: “We’re gonna hit ‘em on land very soon, too,” the president said after months of extrajudicial bombings of vessels in the Caribbean that the administration has alleged with scant evidence are carrying drugs.

On the same day that Machado received the award in absentia, US warplanes were seen circling over the Gulf of Venezuela. Later, in what Bloomberg described as a "serious escalation," the US seized an oil tanker off the nation's coast.

Keep ReadingShow Less

Princeton Experts Speak Out Against Trump Boat Strikes as 'Illegal' and Destabilizing 'Murders'

"Deploying an aircraft carrier and US Southern Command assets to destroy small yolas and wooden boats is not only unlawful, it is an absurd escalation," said one scholar.

Dec 10, 2025

Multiple scholars at the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs on Wednesday spoke out against the Trump administration's campaign of bombing suspected drug boats, with one going so far as to call them acts of murder.

Eduardo Bhatia, a visiting professor and lecturer in public and international affairs at Princeton, argued that it was "unequivocal" that the attacks on on purported drug boats are illegal.

"They violate established maritime law requiring interdiction and arrest before the use of lethal force, and they represent a grossly disproportionate response by the US," stressed Bhatia, the former president of the Senate of Puerto Rico. "Deploying an aircraft carrier and US Southern Command assets to destroy small yolas and wooden boats is not only unlawful, it is an absurd escalation that undermines regional security and diplomatic stability."

Deborah Pearlstein, director of the Program in Law and Public Policy at Princeton, said that she has been talking with "military operations lawyers, international law experts, national security legal scholars," and other experts, and so far has found none who believe the administration's boat attacks are legal.

Pearlstein added that the illegal strikes are "a symptom of the much deeper problem created by the purging of career lawyers on the front end, and the tacit promise of presidential pardons on the back end," the result of which is that "the rule of law loses its deterrent effect."

Visiting professor Kenneth Roth, former executive director of Human Rights Watch, argued that it was not right to describe the administration's actions as war crimes given that a war, by definition, "requires a level of sustained hostilities between two organized forces that is not present with the drug cartels."

Rather, Roth believes that the administration's policy should be classified as straight-up murder.

"These killings are still murders," he emphasized. "Drug trafficking is a serious crime, but the appropriate response is to interdict the boats and arrest the occupants for prosecution. The rules governing law enforcement prohibit lethal force except as a last resort to stop an imminent threat of death or serious bodily injury, which the boats do not present."

International affairs professor Jacob N. Shapiro pointed to the past failures in the US "War on Drugs," and predicted more of the same from Trump's boat-bombing spree.

"In 1986, President Ronald Reagan announced the 'War on Drugs,' which included using the Coast Guard and military to essentially shut down shipment through the Caribbean," Shapiro noted. "The goal was to reduce supply, raise prices, and thereby lower use. Cocaine prices in the US dropped precipitously from 1986 through 1989, and then dropped slowly through 2006. Traffickers moved from air and sea to land routes. That policy did not work, it's unclear why this time will be different."

The scholars' denunciation of the boat strikes came on the same day that the US seized an oil tanker off the coast of Venezuela in yet another escalatory act of aggression intended to put further economic pressure on the government of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro.

Keep ReadingShow Less

Most Popular