The gap between the weekly wages of US public school teachers and other college graduates not only continued to grow last year, but "reached a record high," according to a report released Wednesday by a pair of think tanks.

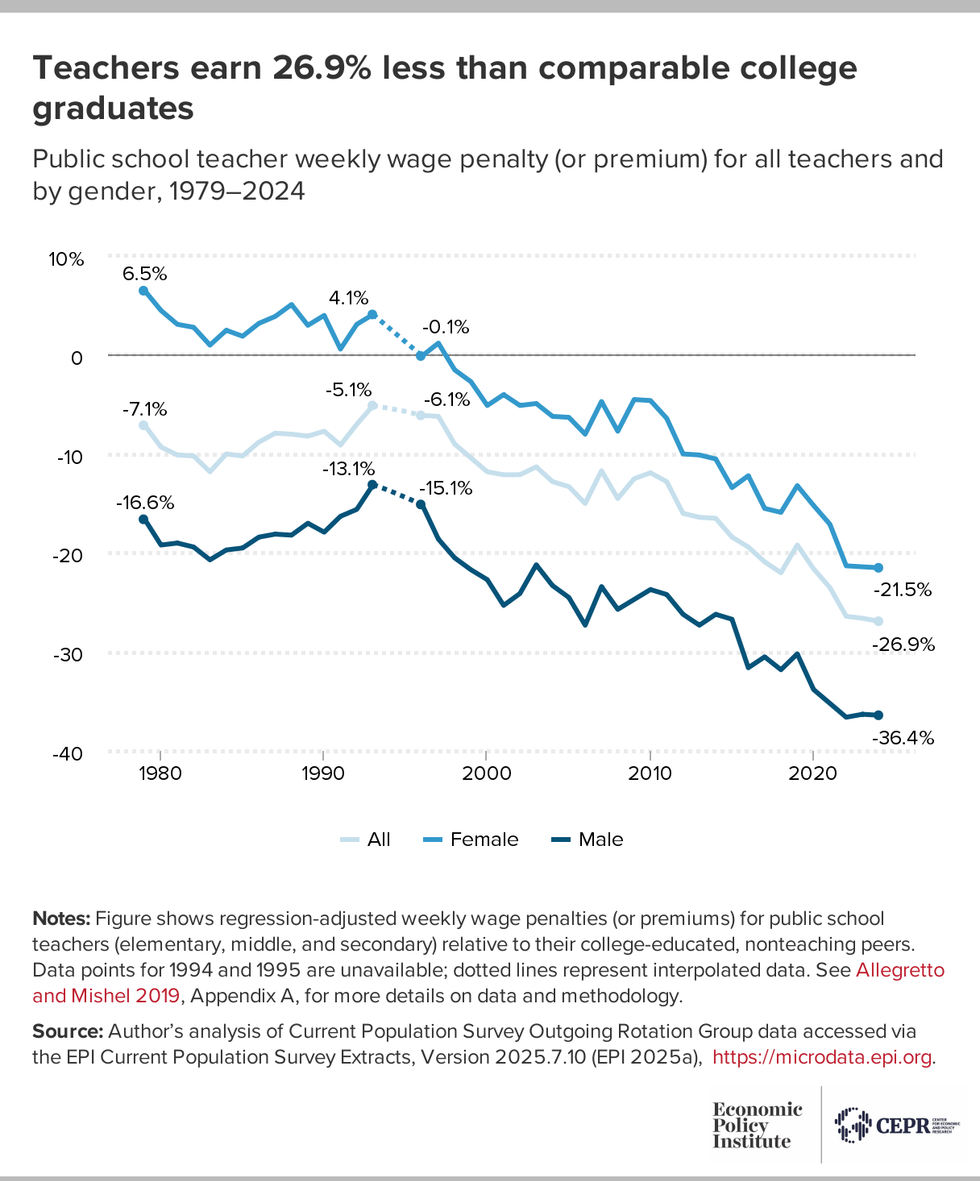

Sylvia Allegretto, a senior economist at the Center for Economic and Policy Research and research associate at the Economic Policy Institute, found that this gap, known as the teacher pay penalty, grew to 26.9% in 2024, "a significant increase from 6.1% in 1996."

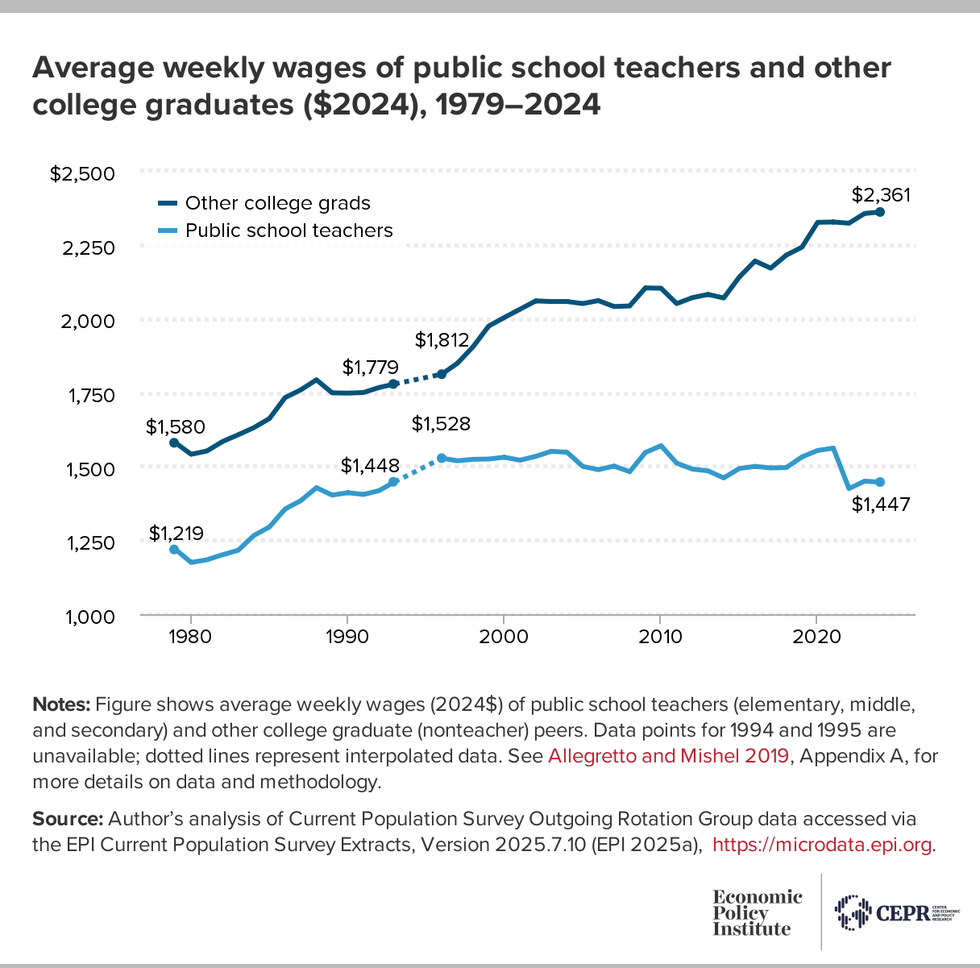

Allegretto tracked data back even further—to 1979, when teachers earned an average of $1,219 a week, while other graduates earned $1,580, adjusted for inflation. In 2024, those figures rose to $1,447 for teachers and $2,361 for other similarly educated workers.

The numbers above are simple averages. The researcher also aimed to "estimate weekly wages of public school teachers relative to other similarly situated college graduates working in other professions," accounting for "ways the two groups may differ fundamentally which typically affect pay on margins such as age, educational attainment, race/ethnicity, and state of residence."

She found a "nearly 30-year trend of relative teacher weekly wages increasingly falling behind those of other similarly qualified professionals." While the gap averaged 8.7% pre-1994, "the shortfall worsened considerably starting in the mid-1990s."

In 1996, "on average, teachers earned 73.1 cents on the dollar in 2024, compared with what similar college graduates earned

working in other professions—much less than the relative 93.9 cents on the dollar that teachers earned in 1996," the report says.

Allegretto also separated workers by gender, and found that while the relative female teacher weekly wage "was at a premium that averaged 3.3%" before 1994, "starting in 1996, the female gap quickly went from parity to a penalty, landing at a 21.5% penalty in 2024."

As the report details:

There is an important story behind the declining relative wages experienced by female teachers. Historically, the teaching profession relied on a somewhat captive labor pool of educated women who had few employment opportunities. This is thankfully no longer the case, but increased opportunity costs are a part of the story and reflected in these results. Expanding opportunities for women enabled them to earn more as they entered occupations and professions from which they were once barred.

In fact, the simple average weekly wages (inflation-adjusted) of female teachers compared with their nonteaching counterparts grew in lock step from 1979 until they started to diverge in the late 1990s. They were close to parity in 1996, when other female college graduates earned just 0.7% more than female teachers. But this divide grew nearly every year—reaching 40.9% in 2024.

Conversely, the trends in the weekly wages of male teachers compared with other male college graduates were never at parity. But like their female counterparts, men also experienced a considerable increase in the pay gap—from 24.1% in 1996 to 81.7% in 2024. Therefore, the regression-adjusted relative wages of male teachers have seen sizable penalties throughout the timeframe of this paper (1979–2024) and in my earlier analyses using 1960, 1970, and 1980 decennial Census data. Over the long run, the male relative penalty worsened from 20.5% in 1960 to 36.3% in 2024.

While all states and the District of Columbia have a wage gap between teachers and similar graduates, Allegretto examined how the penalties vary by state. The biggest penalties since 2019 were recorded in Colorado (38.5%), Alabama (34.3%), Arizona (33.8%), Minnesota (33.3%), and Virginia (32.7%), while the lowest were Rhode Island (10%), Wyoming (11%), New Jersey (12.7%), Vermont (13%), and South Carolina (14.1%).

Allegretto also acknowledged "the view that, on average in the US, teachers generally receive a larger share of their total compensation as benefits—such as health or other insurance and retirement plans—compared with other professionals."

From 2020-24, "the benefits advantage that favors teachers varied from 8.8% to 9.9%, but over the same timeframe the teacher wage penalty grew substantially. Thus, in 2024, the teacher total compensation gap widened to -17.1%—the largest on record," she wrote. "Of course, even if the teacher benefits advantage could exceed the large teacher wage penalty, the standard of living for teachers would likely fall, as they would have little in the way of earnings to make ends meet."

The report says that trends from "the last three decades have no doubt already had profound consequences on teacher retention and recruitment," citing research on staffing challenges, college students forgoing teaching careers due to low wages, parents steering their children into professions that pay better, fast-tracking credentials in response to shortages, the heavy use of unqualified teachers, and the reliance on unqualified substitutes.

"The quality of a public education greatly hinges on our efforts to sufficiently invest in our schools and teachers," the publication stresses, calling for "targeted and sustained investments" at the local, state, and federal levels, and the expansion of collective bargaining.

"Regrettably, sustained and effective policy interventions capable of mitigating, much less substantially improving, the trends outlined in this long-running series have been lacking," concludes the report. "This is a troublesome reality, especially in the United States—a country that has more than enough resources and wealth to be the envy of public education around the world."

The publication comes as President Donald Trump works to dismantle the US Department of Education and elected Republicans, along with some Democrats, try to push tax dollars toward private and charter schools.

Amid such efforts this summer, Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee Ranking Member Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) held a town hall with educators and introduced the Pay Teachers Act, which would ensure they earn at least $60,000 annually, require districts to give raises throughout teachers' careers, and provide at least $1,000 per year for classroom supplies.