February, 02 2011, 11:43am EDT

For Immediate Release

Contact:

Lisa Nurnberger, Media Director, lnurnberger@ucs.org

New Report Recommends Ways to Lower Global Warming Emissions from U.S. Beef Production

Pasture-Fed Beef Has Significant Advantages over CAFOs

WASHINGTON

U.S. beef cattle are responsible for 160 million metric tons of

global warming emissions every year -- equivalent to the annual

emissions from 24 million cars and light trucks. But unlike American

drivers, farmers who raise beef on pasture can reduce global warming

emissions by storing, or sequestering, carbon in pasture soils,

according to a report released today by the Union of Concerned

Scientists (UCS).

"Given the threat that climate change poses, all sectors of our

economy - including agriculture -- have to do their part," said UCS

Senior Scientist Doug Gurian-Sherman, the author of the report. "There

is a range of affordable ways beef producers, especially those who raise

beef on pasture, can significantly reduce their impact by cutting

emissions and capturing more carbon in soil."

The report, "Raising the Steaks: Global Warming and Pasture-Raised

Beef Production in the United States," concluded that U.S. pasture beef

producers could reduce their annual global warming impacts by as much as

140 million metric tons, the equivalent of taking 21 million cars and

light trucks off the road.

Carbon sequestration, the report found, has the most potential for

mitigating pasture beef's climate impact. Such practical methods as

preventing overgrazing, increasing pasture crop productivity with a mix

of crops, and adding adequate amounts of nutrients from manure, legume

crops or fertilizers, could capture significant carbon dioxide (CO2)

emissions from a variety of sources.

Pasture beef farmers also can adopt practices to cut emissions.

Pasture beef cattle emit the three major heat-trapping gases - methane,

nitrous oxide and CO2 - but the amount of CO2 is such a small percentage

of total U.S. global warming emissions that the report did not include

it. Per ton, methane and nitrous oxide are much more damaging to the

climate than CO2. Methane has 23 times the warming effect of CO2, and

nitrous oxide is nearly 300 times worse.

The 35 million head of cattle the U.S. beef industry raises annually

release more than 103 million metric tons of the CO2 equivalent of

methane into the atmosphere. Meanwhile, crop and pasture sources of

nitrogen -- such as manure and fertilizer -- generate 57 million metric

tons of the CO2 equivalent of nitrous oxide.

All beef cattle spend their first months -- and sometimes more than a

year -- on pasture or rangeland, grazing on grass, alfalfa or other

forage crops because feeding cattle grain their entire lives would cause

life-threatening illnesses. Some beef cattle live on pasture until

slaughter, but most U.S. beef cattle are fattened, or "finished," for

several months in CAFOs (confined animal feeding operations) on corn and

other grains.

The UCS report recommended a number of approaches that would reduce

the impact of pasture-raised beef. Most of them are more suitable for

the finishing stage of fully pasture-raised cattle systems -- which have

environmental and nutritional advantages over CAFOs -- but they also

could apply to the many months CAFO-bound cattle spend grazing on

rangeland.

One key is to improve cattle's diet, which, in some tests, reduced

methane production of pasture-raised cattle by 15 to 30 percent. More

research is needed to accurately estimate its potential to reduce cattle

emissions nationally. Animals fed on rapidly growing or more nutritious

types of grasses and other pasture plants, which are more easily

digested, produce less methane than cattle eating older or otherwise

less nutritious pasture plants. On this more climate-friendly diet, the

animals also grow faster, need less food, and therefore produce fewer

emissions.

Gurian-Sherman examined dozens of peer-reviewed studies and found

that cattle fed a mixture of high-quality grasses and legumes such as

alfalfa produced less global warming emissions than animals fed on

grasses alone. One particularly promising legume is a plant known as

birdsfoot trefoil. Like all legumes, it adds nitrogen to the soil, which

improves the productivity of pasture grasses. But unlike most other

legumes, it contains natural chemicals known as condensed tannins, which

reduce methane production during digestion.

There are also ways to reduce nitrous oxide, which is produced by the

action of soil microbes on nitrogen in industrial fertilizers and

manure and crop residues. The report recommends that farmers use only

enough nitrogen to produce adequate pasture crop productivity because

excess use results in especially high rates of nitrous oxide. It also

recommends that farmers spread cattle more evenly around a pasture to

minimize manure buildup in particular spots. That allows more nitrogen

to be absorbed by pasture plants, leaving less for soil microbes to turn

into nitrous oxide.

Some studies have found that CAFO systems

produce less heat-trapping emissions than pasture systems, but those

studies relied on data that assumed low pasture nutritional quality. The

scientific literature documents that planting higher quality pasture

crops, using adequate fertilizer, and managing grazing "intensity" would

substantially reduce the disparity between CAFO and pasture systems.

Smart pasture operations also have other advantages. Pasture-raised

cattle require far fewer antibiotics than CAFO-raised cattle, resulting

in fewer harmful antibiotic-resistant pathogens, such as Salmonella and E. coli. And pasture-raised beef contains healthier fats.

"The Department of Agriculture has a role to play here, too,"

Gurian-Sherman said. "It should sponsor more research to improve pasture

crop quality and productivity, and provide incentives to help farmers

adopt climate-friendly pasture practices."

The report has implications beyond U.S. beef production,

Gurian-Sherman added. Worldwide, beef contributes a substantially

greater proportion of total climate change emissions than it does in the

United States, so adopting these approaches internationally would have a

significant impact. Moreover, beef production is only one facet of

animal agriculture. According to a 2006 report by the U.N. Food and

Agriculture Organization, livestock farming worldwide generates nearly

20 percent of all global warming emissions.

The Union of Concerned Scientists is the leading science-based nonprofit working for a healthy environment and a safer world. UCS combines independent scientific research and citizen action to develop innovative, practical solutions and to secure responsible changes in government policy, corporate practices, and consumer choices.

LATEST NEWS

'We Cannot Be Silent': Tlaib Leads 19 US Lawmakers Demanding Israel Stop Starving Gaza

"This current blockade is starving Palestinian civilians in violation of international law, and the militarization of food will not help."

Jun 30, 2025

As the death toll from Israel's forced starvation of Palestinians continues to rise amid the ongoing U.S.-backed genocidal assault and siege of the Gaza Strip, Rep. Rashida Tlaib on Monday led 18 congressional colleagues in a letter demanding that the Trump administration push for an immediate cease-fire, an end to the Israeli blockade, and a resumption of humanitarian aid into the embattled coastal enclave.

"We are outraged at the weaponization of humanitarian aid and escalating use of starvation as a weapon of war by the Israeli government against the Palestinian people in Gaza," Tlaib (D-Mich.)—the only Palestinian American member of Congress—and the other lawmakers wrote in their letter to U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio. "For over three months, Israeli authorities have blocked nearly all humanitarian aid from entering Gaza, fueling mass starvation and suffering among over 2 million people. This follows over 600 days of bombardment, destruction, and forced displacement, and nearly two decades of siege."

"According to experts, 100% of the population is now at risk of famine, and nearly half a million civilians, most of them children, are facing 'catastrophic' conditions of 'starvation, death, destitution, and extremely critical acute malnutrition levels,'" the legislators noted. "These actions are a direct violation of both U.S. and international humanitarian law, with devastating human consequences."

Gaza officials have reported that hundreds of Palestinians—including at least 66 children—have died in Gaza from malnutrition and lack of medicine since Israel ratcheted up its siege in early March. Earlier this month, the United Nations Children's Fund warned that childhood malnutrition was "rising at an alarming rate," with 5,119 children under the age of 5 treated for the life-threatening condition in May alone. Of those treated children, 636 were diagnosed with severe acute malnutrition, the most lethal form of the condition.

Meanwhile, nearly 600 Palestinians have been killed and more than 4,000 others have been injured as Israeli occupation forces carry out near-daily massacres of desperate people seeking food and other humanitarian aid at or near distribution sites run by the U.S.-backed Gaza Humanitarian Foundation (GHF). Israel Defense Forces officers and troops have said that they were ordered to shoot and shell aid-seeking Gazans, even when they posed no threat.

"This is not aid," the lawmakers' letter argues. "UNRWA Commissioner-General Philippe Lazzarini has warned that, under the GHF, 'aid distribution has become a death trap.' We cannot allow this to continue."

"We strongly oppose any efforts to dismantle the existing U.N.-led humanitarian coordination system in Gaza, which is ready to resume operations immediately once the blockade is lifted," the legislators wrote. "Replacing this system with the GHF further restricts lifesaving aid and undermines the work of long-standing, trusted humanitarian organizations. The result of this policy will be continued starvation and famine."

"We cannot be silent. This current blockade is starving Palestinian civilians in violation of international law, and the militarization of food will not help," the lawmakers added. "We demand an immediate end to the blockade, an immediate resumption of unfettered humanitarian aid entry into Gaza, the restoration of U.S. funding to UNRWA, and an immediate and lasting cease-fire. Any other path forward is a path toward greater hunger, famine, and death."

Since launching the retaliatory annihilation of Gaza in response to the Hamas-led October 7, 2023 attack on Israel, Israeli forces have killed at least 56,531 Palestinians and wounded more than 133,600 others, according to the Gaza Health Ministry, which also says over 14,000 people are missing and presumed dead and buried beneath rubble. Upward of 2 million Gazans have been forcibly displaced, often more than once.

On Sunday, U.S. President Donald Trump reiterated a call for a cease-fire deal that would secure the release of the remaining 22 living Israeli and other hostages held by Hamas.

In addition to Tlaib, the letter to Rubio was signed by Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) and Democratic Reps. Greg Casar (Texas), Jesús "Chuy" García (Ill.), Al Green (Texas), Jonathan Jackson (Ill.), Pramila Jayapal (Wash.), Henry "Hank"Johnson (Ga.), Summer Lee (Pa.), Jim McGovern (Mass.), Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (N.Y.), Ilhan Omar (Minn.), Chellie Pingree (Maine), Mark Pocan (Wisc.), Ayanna Pressley (Mass.), Delia Ramirez (Ill.), Paul Tonko (N.Y.), Nydia Velázquez (N.Y.), and Bonnie Watson Coleman (N.J.).

Keep ReadingShow Less

Biden National Security Adviser Among Those Crafting 'Project 2029' Policy Agenda for Democrats

"Jake Sullivan's been a critical decision-maker in every Democratic catastrophe of the last decade," said one observer. "Why is he still in the inner circle?"

Jun 30, 2025

Amid the latest battle over the direction the Democratic Party should move in, a number of strategists and political advisers from across the center-left's ideological spectrum are assembling a committee to determine the policy agenda they hope will be taken up by a Democratic successor to President Donald Trump.

Some of the names on the list of people crafting the agenda—named Project 2029, an echo of the far-right Project 2025 blueprint Trump is currently enacting—left progressives with deepened concerns that party insiders have "learnt nothing" and "forgotten nothing" from the president's electoral victories against centrist Democratic candidates over the past decade, as one economist said.

The project is being assembled by former Democratic speechwriter Andrei Cherny, now co-founder of the policy journal Democracy: A Journal of Ideas, and includes Jake Sullivan, a former national security adviser under the Biden administration; Jim Kessler, founder of the centrist think tank Third Way; and Neera Tanden, president of the Center for American Progress and longtime adviser to former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton.

Progressives on the advisory board for the project include economist Justin Wolfers and former Roosevelt Institute president Felicia Wong, but antitrust expert Hal Singer said any policy agenda aimed at securing a Democratic victory in the 2028 election "needs way more progressives."

As The New York Times noted in its reporting on Project 2029, the panel is being convened amid extensive infighting regarding how the Democratic Party can win back control of the White House and Congress.

After democratic socialist and state Assemblymember Zohran Mamdani's (D-36) surprise win against former New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo last week in New York City's mayoral primary election—following a campaign with a clear-eyed focus on making childcare, rent, public transit, and groceries more affordable—New York City has emerged as a battleground in the fight. Influential Democrats including House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries (D-N.Y.) and Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (D-N.Y.) have so far refused to endorse him and attacked him for his unequivocal support for Palestinian rights.

Progressives have called on party leaders to back Mamdani, pointing to his popularity with young voters, and accept that his clear message about making life more affordable for working families resonated with Democratic constituents.

But speaking to the Times, Democratic pollster Celinda Lake exemplified how many of the party's strategists have insisted that candidates only need to package their messages to voters differently—not change the messages to match the political priorities of Mamdani and other popular progressives like Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.).

"We didn't lack policies," Lake told the Times of recent national elections. "But we lacked a functioning narrative to communicate those policies."

Sanders and Ocasio-Cortez have drawn crowds of thousands in red districts this year at Sanders' Fighting Oligarchy rallies—another sign, progressives say, that voters are responding to politicians who focus on billionaires' outsized control over the U.S. political system and on economic justice.

Project 2029's inclusion of strategists like Kessler, who declared economic populism "a dead end for Democrats" in 2013, demonstrates "the whole problem [with Democratic leadership] in a nutshell," said Jonathan Cohn of Progressive Mass—as does Sullivan's seat on the advisory board.

As national security adviser to President Joe Biden, Sullivan played a key role in the administration's defense and funding of Israel's assault on Gaza, which international experts and human rights groups have said is a genocide.

"Jake Sullivan's been a critical decision-maker in every Democratic catastrophe of the last decade: Hillary Clinton's 2016 campaign, the withdrawal from Afghanistan, the Israel/Gaza War, and the 2024 Joe Biden campaign," said Nick Field of the Pennsylvania Capital-Star. "Why is he still in the inner circle?"

"Jake Sullivan is shaping domestic policy for the next Democratic administration," he added. "Who is happy with the Biden foreign policy legacy?"

Keep ReadingShow Less

Rick Scott Pushes Amendment to GOP Budget Bill That Could Kick Millions More Off Medicaid

Scott's proposal for more draconian cuts has renewed scrutiny regarding his past as a hospital executive, where he oversaw the "largest government fraud settlement ever," which included stealing from Medicaid.

Jun 30, 2025

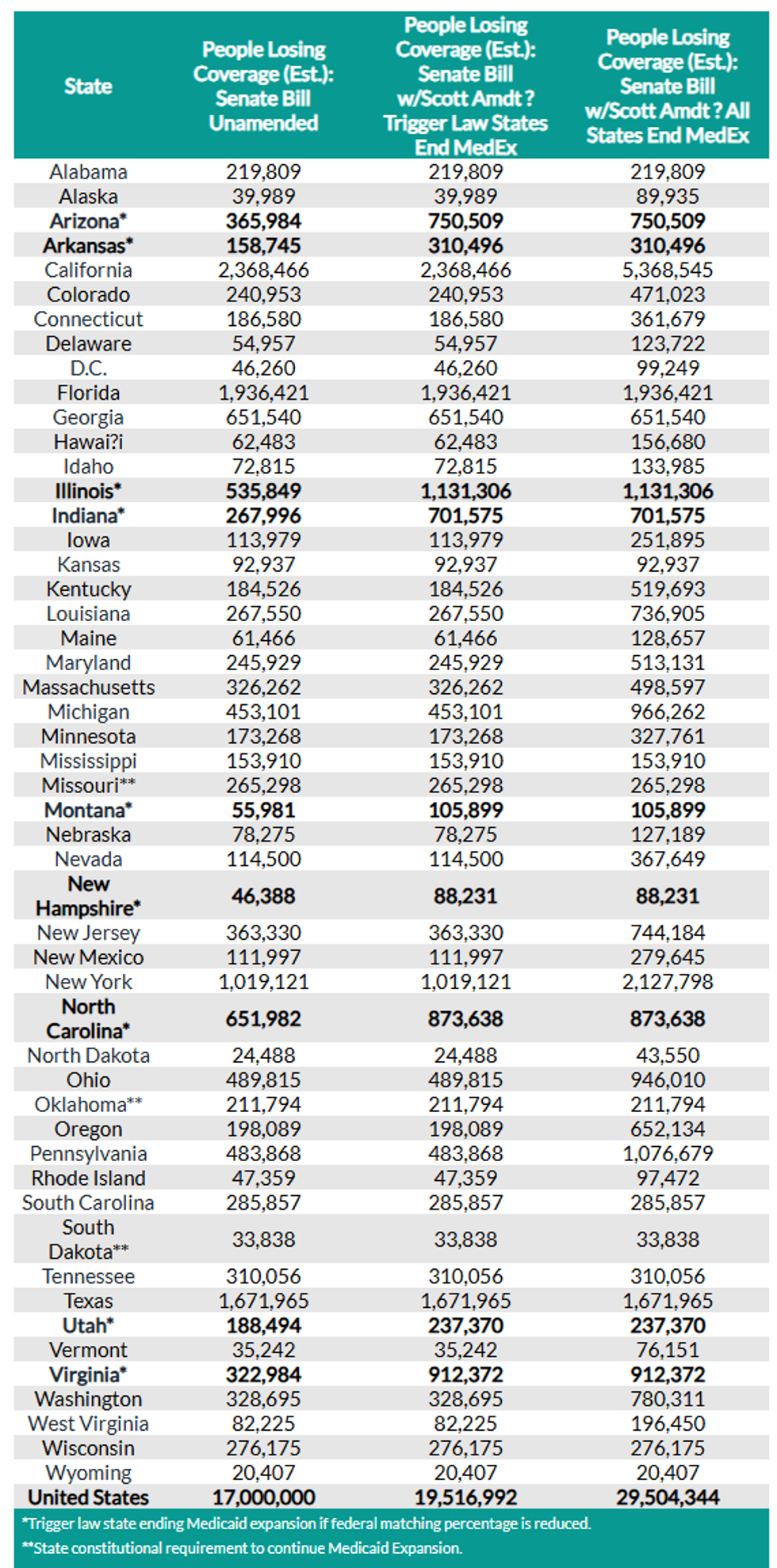

Sen. Rick Scott has introduced an amendment to the Republican budget bill that would slash another $313 million from Medicaid and kick off millions more recipients.

The latest analysis by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) found that 17 million people could lose their health insurance by 2034 as the result of the bill as it already exists.

According to a preliminary estimate by the Democrats on the Joint Congressional Economic Committee, that number could balloon up to anywhere from 20 to 29 million if Scott's (R-Fla.) amendment passes.

The amendment will be voted on as part of the Senate's vote-a-rama, which is expected to run deep into Monday night and possibly into Tuesday morning.

"If Sen. Rick Scott's amendment gets put forward, this would be a self-inflicted healthcare crisis," said Tahra Hoops, director of economic analysis at Chamber of Progress.

The existing GOP reconciliation package contains onerous new restrictions, including new work requirements and administrative hurdles, that will make it harder for poor recipients to claim Medicaid benefits.

Scott's amendment targets funding for the program by ending the federal government's 90% cost sharing for recipients who join Medicaid after 2030. Those who enroll after that date would have their medical care reimbursed by the federal government at a lower rate of 50%.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) introduced the increased rate in 2010 to incentivize states to expand Medicaid, allowing more people to be covered.

Scott has said his program would "grandfather" in those who had already been receiving the 90% reimbursement rate.

However, Medicaid is run through the states, which will have to spend more money to keep covering those who need the program after 2030.

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities estimated that this provision "would shift an additional $93 billion in federal Medicaid funding to states from 2031 through 2034 on top of the cuts already in the Senate bill."

This will almost certainly result in states having to cut back, by introducing their stricter requirements or paperwork hurdles.

Additionally, nine states have "trigger laws" that are set to end the program immediately if the federal matching rate is reduced: Arizona, Arkansas, Illinois, Indiana, Montana, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Utah, and Virginia.

The Joint Congressional Economic Committee estimated Tuesday that around 2.5 million more people will lose their insurance as a result of those cuts.

If all the states with statutory Medicaid expansion ended it as a result of Scott's cuts, as many as 12.5 million could lose their insurance. Combined with the rest of the bill, that's potentially 29 million people losing health insurance coverage, the committee said.

There are enough Republicans in the Senate to pass the bill with Scott's amendment. However, they can afford no more than three defections. According to Politico, Sens. Rand Paul (R-Ky.) and Thom Tillis (R-N.C.) have signaled they will vote against the amendment.

Sen. Jim Justice (R-W.V.) also said he'd "have a hard time" voting yes on the bill if Scott's amendment passed. His state of West Virginia has the second-highest rate of people using federal medical assistance of any state in the country, behind only Mississippi.

Critics have called out Scott for lying to justify this line of cuts. In a recent Fox News appearance, Scott claimed that his new restrictions were necessary to stop Democrats who want to "give illegal aliens Medicaid benefits," even though they are not eligible for the program.

Scott's proposal has also brought renewed scrutiny to his past as a healthcare executive.

"Ironically enough, some of the claims against Scott's old hospital company revolved around exploiting Medicaid, and billing for services that patients didn't need," wrote Andrew Perez in Rolling Stone Monday.

In 2000, Scott's hospital company, HCA, was forced to pay $840 million in fines, penalties, and damages to resolve claims of unlawful billing practices in what was called the "largest government fraud settlement ever." Among the charges were that during Scott's tenure, the company overbilled Medicare and Medicaid by pretending patients were sicker than they actually were.

The company entered an additional settlement in 2003, paying out another $631 million to compensate for the money stolen from these and other government programs.

Scott himself was never criminally charged, but resigned in 1997 as the Department of Justice began to probe his company's activities. Despite the scandal, Scott not only became a U.S. senator, but is the wealthiest man in Congress, with a net worth of more than half a billion dollars.

The irony of this was not lost on Perez, who wrote: "A few decades later, Scott is now trying to extract a huge amount of money from state Medicaid funds to help finance Trump's latest round of tax cuts for the rich."

Keep ReadingShow Less

Most Popular