SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

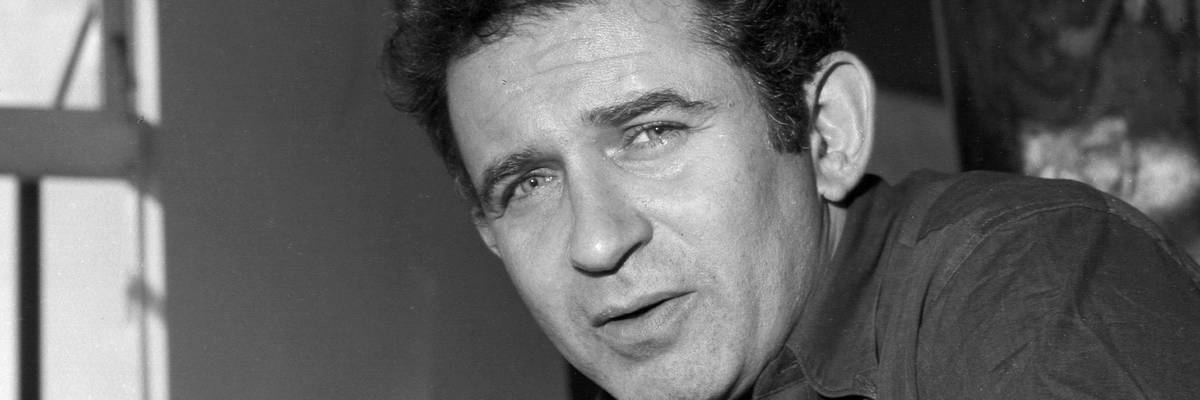

Portrait of American author Norman Mailer (1923 - 2007) taken in1962. (Photo: Fred Stein Archive/Archive Photos/Getty Images)

A 1957 essay by celebrated writer Norman Mailer called "The White Negro" is getting a lot of renewed attention these days. According to a just-published article by journalist Michael Wolff in a site called The Ankler, Random House decided against publishing a collection of Mailer's essays after a "junior staffer" complained about "The White Negro," which was going to be included in the anthology. According to Wolff, the staffer believed that the title was racist and that was enough for Random House to scuttle the project in order to avoid controversy. This quickly triggered a debate on social media over so-called "cancel culture." Did the nation's largest book publisher cancel the Mailer book over fears of being called racist?

Subsequent reporting revealed that Random House was in discussions with Mailer's family about publishing a collection of his writings in 2023 to celebrate the 100th anniversary of his birth, but that no contract had yet been signed. After Random House nixed the project, Skyhorse--a much smaller publisher that lacks Random House's prestige and marketing capacity--agreed to publish the book

In recent years, Random House--which is owned by Bertelsmann, a huge German company--has "gobbled up" (in Wolff's words) other publishers. A deal to acquire its biggest rival, Simon & Schuster, for $2 billion, is now pending. The federal Justice Department is currently suing the two companies for violating anti-trust laws, concerned about the concentration of ownership in the publishing industry. One shouldn't be surprised that Random House, while in the middle of fighting the Justice Department, didn't want to get ensnared in a controversy over whether one of Mailer's essays is racist.

Since the upsurge of protest following the murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis cop in May 2020, and the adoption of voter suppression laws by states that target Black voters, hundreds of big corporations have issued public statements opposing racism. Unfortunately, few of them have changed their discriminatory business practices and many of them continue to make political contributions to Republican candidates who endorse the white-supremacist policy agenda that opposes voting rights and social programs to lift Americans out of poverty.

It still isn't clear why Random House got cold feet or whether the inclusion of "The White Negro" had anything to do with it. But if the controversy draws attention to that 65-year old essay, it will have served a useful purpose. It was provocative and controversial when it was first published in the Fall 1957 issue of Dissent, a quarterly magazine. It is worth re-reading today not only as a historical artifact but as a way of revealing how discussions of racism have evolved in society in general and on the Left in particular.

Dissent was then a relatively new socialist magazine, having published its first issue in 1954. Starting a socialist magazine in the midst of the Cold War and McCarthyism was a bold move by its editors, literary critic Irving Howe and sociologist Lewis Coser. They published many articles by up-and-coming as well as prominent academics, journalists, novelists, and activists on political, sociological, and literary topics that challenged mainstream orthodoxy and stirred controversy.

The Dissent editors considered it a coup to get a well-known writer like Mailer to publish an essay in their still-obscure magazine. He would become much more famous, and more controversial, in subsequent years. He was not only a respected writer but also a cultural celebrity. He published a dozen novels and 20 nonfiction books as well as screenplays, stage plays, TV miniseries, two books of poetry, collections of short stories, and hundreds of essays and journalistic profiles.

One of his best articles is "Superman Comes to the Supermarket," a long essay published in Esquire magazine in November 1960 about John F. Kennedy, whom Mailer described as an "existential hero" whose election as president could save the country from the boring eight years of Dwight Eisenhower's presidency and the stultifying cultural and political conformity of the 1950s. That article was Mailer's first foray into a new form of on-the-scene political journalism, in which he became a character in the story. He further developed that approach to political reporting in two books--Miami and the Siege of Chicago (about the 1968 Democratic and Republican conventions) and Armies of the Night (about the 1967 protest at the Pentagon), which won the Pulitzer Prize. He also won a Pulitzer for his 1979 crime novel The Executioner's Song, which examines the execution of Gary Gilmore for murder by the state of Utah. This work clearly surpasses his later writings about women, the space program, and boxing.

Mailer was amazingly prolific. He was married six times, had nine children, and had to pay a lot of alimony, so he dashed off many articles and books, resulting in a very uneven track record. He enjoyed being the center of attention. In 1969, he ran unsuccessfully in the Democratic Party primary for New York City mayor on a left-wing agenda, finishing fourth in a field of five. He was a self-promoting, inflammatory, macho bully who once, while drunk at a party, stabbed one of his wives with a knife. He was a frequent guest on TV talk shows. He wore his homophobia on his sleeve. He stirred public battles with other writers, like Gore Vidal, another prominent novelist and polemicist, who was gay. Mailer once punched Vidal at party, knocking him to the floor. Before he got up, Vidal said, "Norman, once again words have failed you."

Mailer became well known for his first novel, The Naked and the Dead, published in 1948, which drew on his experiences as a soldier in World War II. He published two other novels before he began writing journalistic essays for magazines. "The White Negro," was one of his first journalistic pieces.

Let's acknowledge up-front that "The White Negro" is deeply flawed. The essay has some nice turns-of-phrases, but much of it is over-written and some of it is barely readable. Mailer spends too many of its rambling 9,000 words writing about sex and orgies, clearly meant to shock readers. It includes a lot of third-rate psychology--for example, explicating the difference between psychopaths and psychotics. And, as discussed below, it includes some ugly racist stereotypes. My friend Adrian Walker, a Boston Globe columnist, reminded me that James Baldwin wrote an insightful critique of Mailer's essay, which he called, "The Black Boy Looks at the White Boy Norman Mailer," published in Esquire in 1961.

But despite its defects, "The White Negro" tapped into an aspect of American society --the growing alienation of white Americans from the dominant sociological and cultural trends--that few writers at the time had recognized.

The title of Mailer's essay, "The White Negro," can be confusing. It might lead one to assume that it is about middle class Black Americans trying to assimilate into white American culture. That is a topic that the left-wing sociologist Franklin Frazier explored in his scathing book Black Bourgeoisie, initially published in French in 1955 and translated into English two years later, the same year that Mailer's "The White Negro" appeared.

"The White Negro" is mostly about white people, not Black people. It is about the efforts of some white hipsters--mostly bohemians but also radicals--to appropriate (although he didn't use that word) Black culture and style. "Hipster" back then meant something different than it does now. By that word, Mailer meant a growing sense of alienation from and opposition to mainstream white middle class conformist (and increasingly suburban) America. According to Mailer, this was a version of "existentialism"--a philosophical and psychological attempt to cope with the irrationality, violence, and soul-killing destructiveness of post-war America, then only a decade removed from World War II, and the understanding that the Holocaust and concentration camps can happen in so-called advanced societies. The existential stance was also a way of coping with the looming threat of an atomic war (and the air-raid drills that all school kids had to endure), which many Americans believed they had little power to stop.

In "The White Negro," the 34-year old Mailer described the growing unease of some members of his own generation as well as the next generation (the baby boomers) of white Americans. Mailer wrote that Black Americans had to deal with the worst aspects of American society every day, especially violence, poverty, and overt discrimination by cops, employers, banks, the media, and other institutions. By embracing some aspects of Black urban culture--including jazz, marijuana, language, and what would later called "cool"--white hipsters were saying that they didn't buy into the dominant cultural and/or political conformity of the period, including consumerism, suburbanization, the Cold War, TV culture, dull public schools, and large factory-like universities. A few years later, Bob Dylan would echo Mailer's sentiments in his song, "Ballad of a Thin Man," which declared: "Because something is happening here but you don't know what it is. Do you, Mr. Jones?"

According to Mailer, the white hipsters, too, were alienated from the dominant culture. The concept of alienation was gaining currency at the time. Some used the word to explain the rise of "juvenile delinquency," primarily among white youth, which was a topic of much journalistic, academic, and political discussion at the time. It was the subject of the 1953 film "The Wild One" starring Marlon Brando as the leader of a motorcycle gang. (Asked "What are you rebelling against, Johnny?", Brando answers "Whaddaya got?"). Juvenile delinquency was also the focus of two popular 1955 films--"Blackboard Jungle" and "Rebel Without a Cause." In his essay, Mailer referred to the 1944 book Rebel Without A Cause--The Hypnoanalysis of a Criminal Psychopath by Robert Lindner, but not to the film, which made James Dean an idol of the white hipsters Mailer was writing about. (In 1960, the sociologists Richard Cloward and Lloyd Ohlin wrote a book, Delinquency and Opportunity, which argued that low-income and working class youth engage in criminal and semi-criminal activity because they lack the opportunities to succeed in mainstream society, not because they are opposed to mainstream values).

For Mailer, the white "hipster" was a culture rebel, not a criminal. These attitudes were expressed through bohemian (pre-hippie) culture. Mailer was describing a growing mood, but he didn't provide any specific examples, which were all around him, including beat poetry like Allen Ginsberg's Howl (published in 1956), the satirical and anti-establishment MAD magazine (founded in 1952), and Sloan Wilson's novel The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit (published in 1955).

Mailer was certainly familiar with another prominent example--Jack Kerouac's hipster novel On the Road, also published in 1957--which included the author's description of a spending time in the "Denver colored section, wishing I were a Negro, feeling that the best the white world had offered was not enough ecstasy for me, not enough life, joy, kicks, darkness, music, not enough night." Mailer should have given Kerouac some credit for inspiring "The White Negro."

Folk music was also part of the white hipster culture, but in 1957 it was not explicitly political, due in part to the blacklisting of Pete Seeger and the Weavers in the early 1950s because of their left-wing views. The first breakthrough commercial success of the folk revival was the Kingston Trio's 1958 hit, the apolitical song "Tom Dooley." Other expressions of this cultural rebellion included Malvina Reynold's song, "Little Boxes" (recorded in 1962) and the commentary of comedian Lenny Bruce (whose first album, "The Sick Humor of Lenny Bruce," came out in 1959).

The mainstream media didn't quite know how to deal with these white hipsters. It mostly made fun of them, reflected in the character of Maynard G. Krebs in the popular TV show "Dobie Gillis," which began in 1959. Krebs wore a goatee, played the bongo drums, wore unkempt and unfashionable clothes, and was allergic to work. "Dobie Gillis" was the first network TV show to feature teenagers (i.e. early baby-boomers) as leading characters. (One of the actors, Sheila Kuehl--who played the nerdy Zelda Gilroy--years later became a prominent feminist lawyer and the first open lesbian elected to the California state legislature and became a powerful state Senator and LA County supervisor).

Mailer believed that "The White Negro" displayed sympathy for the plight of Black Americans. To the extent that Black people engaged in anti-social or even criminal behavior, Mailer thought that it was a way to cope with the harsh realities of racism. He was not blaming the victim, but blaming the system. Even so, "The White Negro" includes a number of uncomfortable racist stereotypes, including a line in which Mailer described the "courage" of "two strong eighteen-year-old hoodlums" in beating "in the brains of a candy store owner." (The hoodlums were Black and the store owner white). The essay also includes this embarrassing, and embarrassingly-long, sentence:

"Knowing in the cells of his existence that life was war, nothing but war, the Negro (all exceptions admitted) could rarely afford the sophisticated inhibitions of civilization, and so he kept for his survival the art of the primitive, he lived in the enormous present, he subsisted for his Saturday night kicks, relinquishing the pleasures of the mind for the more obligatory pleasures of the body, and in his music he gave voice to the character and quality of his existence, to his rage and the infinite variations of joy, lust, languor, growl, cramp, pinch, scream and despair of his orgasm."

This section of the essay foreshadows psychiatrist Frantz Fanon's 1961 book, The Wretched of the Earth, about the therapeutic uses of violence to challenge dehumanizing colonialism. Fanon was writing about Third World peasants, but his analysis became popular among some portions of the white American New Left, who viewed the urban riots of the 1960s as a form of political protest and rebellion and who supported militants in the Black community who believed it was necessary to "pick up the gun" to defend themselves against police brutality.

Even many radicals, however, viewed such views as nihilistic and counter-productive. This is one reason why, in his 1984 autobiography A Margin of Hope, Howe expressed second thoughts about publishing Mailer's essay. Howe acknowledged that, at the time, it was a coup for Dissent to have someone of Mailer's fame write for the magazine, and to do so without getting paid. But ultimately Howe concluded that "it had been unprincipled to accept this essay for Dissent."

Mailer's view of the white hipster was ambivalent. Mailer considered himself a socialist and he viewed the psychological alienation and cultural rebellion of white hipsters as too apolitical, a failure of will. Yet Mailer completely ignored the emergence of at least two kinds of political rebellion that were already underway when he wrote his essay. One was the civil rights movement. The bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama, triggered by the refusal of NAACP activist Rosa Parks to move from her seat on a segregated bus, began in December 1955. The boycott lasted a year, forced the city to desegregate the buses, catapulted Martin Luther King to national fame, and catalyzed the modern civil rights movement, including the lunch counter sit-ins and Freedom Rides a few years later. It also mobilized large numbers of white baby-boomers who got involved in the protest movement. It is inconceivable that Mailer failed to mention this.

The other political rebellion was the "ban the bomb" movement, led by pacifists, that engaged in hundreds of acts of civil disobedience around the country (and around the world) to pressure the U.S. government (as well as the Soviet Union) to halt the use of nuclear weapons and nuclear testing. That campaign, which challenged the premises of the Cold War arms race, eventually led President Kennedy and the Soviets to agree to a Limited Nuclear Test Ban treaty on August 5, 1963, three months before JFK was assassinated. The small cadre of pacifists who led the ban-the-bomb movement became the core of the much-larger anti-Vietnam movement a few years later.

Although Mailer failed to mention these burgeoning movements, he recognized that something was happening below-the-surface in society and he tried to describe and explain it. For all its many inexcusable flaws, "The White Negro" was an important essay for its time and a yardstick for measuring how we discuss race today. Fortunately Dissent has kept it on its website, so you don't have to wait for the Mailer anthology from Skyhorse to read it.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

A 1957 essay by celebrated writer Norman Mailer called "The White Negro" is getting a lot of renewed attention these days. According to a just-published article by journalist Michael Wolff in a site called The Ankler, Random House decided against publishing a collection of Mailer's essays after a "junior staffer" complained about "The White Negro," which was going to be included in the anthology. According to Wolff, the staffer believed that the title was racist and that was enough for Random House to scuttle the project in order to avoid controversy. This quickly triggered a debate on social media over so-called "cancel culture." Did the nation's largest book publisher cancel the Mailer book over fears of being called racist?

Subsequent reporting revealed that Random House was in discussions with Mailer's family about publishing a collection of his writings in 2023 to celebrate the 100th anniversary of his birth, but that no contract had yet been signed. After Random House nixed the project, Skyhorse--a much smaller publisher that lacks Random House's prestige and marketing capacity--agreed to publish the book

In recent years, Random House--which is owned by Bertelsmann, a huge German company--has "gobbled up" (in Wolff's words) other publishers. A deal to acquire its biggest rival, Simon & Schuster, for $2 billion, is now pending. The federal Justice Department is currently suing the two companies for violating anti-trust laws, concerned about the concentration of ownership in the publishing industry. One shouldn't be surprised that Random House, while in the middle of fighting the Justice Department, didn't want to get ensnared in a controversy over whether one of Mailer's essays is racist.

Since the upsurge of protest following the murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis cop in May 2020, and the adoption of voter suppression laws by states that target Black voters, hundreds of big corporations have issued public statements opposing racism. Unfortunately, few of them have changed their discriminatory business practices and many of them continue to make political contributions to Republican candidates who endorse the white-supremacist policy agenda that opposes voting rights and social programs to lift Americans out of poverty.

It still isn't clear why Random House got cold feet or whether the inclusion of "The White Negro" had anything to do with it. But if the controversy draws attention to that 65-year old essay, it will have served a useful purpose. It was provocative and controversial when it was first published in the Fall 1957 issue of Dissent, a quarterly magazine. It is worth re-reading today not only as a historical artifact but as a way of revealing how discussions of racism have evolved in society in general and on the Left in particular.

Dissent was then a relatively new socialist magazine, having published its first issue in 1954. Starting a socialist magazine in the midst of the Cold War and McCarthyism was a bold move by its editors, literary critic Irving Howe and sociologist Lewis Coser. They published many articles by up-and-coming as well as prominent academics, journalists, novelists, and activists on political, sociological, and literary topics that challenged mainstream orthodoxy and stirred controversy.

The Dissent editors considered it a coup to get a well-known writer like Mailer to publish an essay in their still-obscure magazine. He would become much more famous, and more controversial, in subsequent years. He was not only a respected writer but also a cultural celebrity. He published a dozen novels and 20 nonfiction books as well as screenplays, stage plays, TV miniseries, two books of poetry, collections of short stories, and hundreds of essays and journalistic profiles.

One of his best articles is "Superman Comes to the Supermarket," a long essay published in Esquire magazine in November 1960 about John F. Kennedy, whom Mailer described as an "existential hero" whose election as president could save the country from the boring eight years of Dwight Eisenhower's presidency and the stultifying cultural and political conformity of the 1950s. That article was Mailer's first foray into a new form of on-the-scene political journalism, in which he became a character in the story. He further developed that approach to political reporting in two books--Miami and the Siege of Chicago (about the 1968 Democratic and Republican conventions) and Armies of the Night (about the 1967 protest at the Pentagon), which won the Pulitzer Prize. He also won a Pulitzer for his 1979 crime novel The Executioner's Song, which examines the execution of Gary Gilmore for murder by the state of Utah. This work clearly surpasses his later writings about women, the space program, and boxing.

Mailer was amazingly prolific. He was married six times, had nine children, and had to pay a lot of alimony, so he dashed off many articles and books, resulting in a very uneven track record. He enjoyed being the center of attention. In 1969, he ran unsuccessfully in the Democratic Party primary for New York City mayor on a left-wing agenda, finishing fourth in a field of five. He was a self-promoting, inflammatory, macho bully who once, while drunk at a party, stabbed one of his wives with a knife. He was a frequent guest on TV talk shows. He wore his homophobia on his sleeve. He stirred public battles with other writers, like Gore Vidal, another prominent novelist and polemicist, who was gay. Mailer once punched Vidal at party, knocking him to the floor. Before he got up, Vidal said, "Norman, once again words have failed you."

Mailer became well known for his first novel, The Naked and the Dead, published in 1948, which drew on his experiences as a soldier in World War II. He published two other novels before he began writing journalistic essays for magazines. "The White Negro," was one of his first journalistic pieces.

Let's acknowledge up-front that "The White Negro" is deeply flawed. The essay has some nice turns-of-phrases, but much of it is over-written and some of it is barely readable. Mailer spends too many of its rambling 9,000 words writing about sex and orgies, clearly meant to shock readers. It includes a lot of third-rate psychology--for example, explicating the difference between psychopaths and psychotics. And, as discussed below, it includes some ugly racist stereotypes. My friend Adrian Walker, a Boston Globe columnist, reminded me that James Baldwin wrote an insightful critique of Mailer's essay, which he called, "The Black Boy Looks at the White Boy Norman Mailer," published in Esquire in 1961.

But despite its defects, "The White Negro" tapped into an aspect of American society --the growing alienation of white Americans from the dominant sociological and cultural trends--that few writers at the time had recognized.

The title of Mailer's essay, "The White Negro," can be confusing. It might lead one to assume that it is about middle class Black Americans trying to assimilate into white American culture. That is a topic that the left-wing sociologist Franklin Frazier explored in his scathing book Black Bourgeoisie, initially published in French in 1955 and translated into English two years later, the same year that Mailer's "The White Negro" appeared.

"The White Negro" is mostly about white people, not Black people. It is about the efforts of some white hipsters--mostly bohemians but also radicals--to appropriate (although he didn't use that word) Black culture and style. "Hipster" back then meant something different than it does now. By that word, Mailer meant a growing sense of alienation from and opposition to mainstream white middle class conformist (and increasingly suburban) America. According to Mailer, this was a version of "existentialism"--a philosophical and psychological attempt to cope with the irrationality, violence, and soul-killing destructiveness of post-war America, then only a decade removed from World War II, and the understanding that the Holocaust and concentration camps can happen in so-called advanced societies. The existential stance was also a way of coping with the looming threat of an atomic war (and the air-raid drills that all school kids had to endure), which many Americans believed they had little power to stop.

In "The White Negro," the 34-year old Mailer described the growing unease of some members of his own generation as well as the next generation (the baby boomers) of white Americans. Mailer wrote that Black Americans had to deal with the worst aspects of American society every day, especially violence, poverty, and overt discrimination by cops, employers, banks, the media, and other institutions. By embracing some aspects of Black urban culture--including jazz, marijuana, language, and what would later called "cool"--white hipsters were saying that they didn't buy into the dominant cultural and/or political conformity of the period, including consumerism, suburbanization, the Cold War, TV culture, dull public schools, and large factory-like universities. A few years later, Bob Dylan would echo Mailer's sentiments in his song, "Ballad of a Thin Man," which declared: "Because something is happening here but you don't know what it is. Do you, Mr. Jones?"

According to Mailer, the white hipsters, too, were alienated from the dominant culture. The concept of alienation was gaining currency at the time. Some used the word to explain the rise of "juvenile delinquency," primarily among white youth, which was a topic of much journalistic, academic, and political discussion at the time. It was the subject of the 1953 film "The Wild One" starring Marlon Brando as the leader of a motorcycle gang. (Asked "What are you rebelling against, Johnny?", Brando answers "Whaddaya got?"). Juvenile delinquency was also the focus of two popular 1955 films--"Blackboard Jungle" and "Rebel Without a Cause." In his essay, Mailer referred to the 1944 book Rebel Without A Cause--The Hypnoanalysis of a Criminal Psychopath by Robert Lindner, but not to the film, which made James Dean an idol of the white hipsters Mailer was writing about. (In 1960, the sociologists Richard Cloward and Lloyd Ohlin wrote a book, Delinquency and Opportunity, which argued that low-income and working class youth engage in criminal and semi-criminal activity because they lack the opportunities to succeed in mainstream society, not because they are opposed to mainstream values).

For Mailer, the white "hipster" was a culture rebel, not a criminal. These attitudes were expressed through bohemian (pre-hippie) culture. Mailer was describing a growing mood, but he didn't provide any specific examples, which were all around him, including beat poetry like Allen Ginsberg's Howl (published in 1956), the satirical and anti-establishment MAD magazine (founded in 1952), and Sloan Wilson's novel The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit (published in 1955).

Mailer was certainly familiar with another prominent example--Jack Kerouac's hipster novel On the Road, also published in 1957--which included the author's description of a spending time in the "Denver colored section, wishing I were a Negro, feeling that the best the white world had offered was not enough ecstasy for me, not enough life, joy, kicks, darkness, music, not enough night." Mailer should have given Kerouac some credit for inspiring "The White Negro."

Folk music was also part of the white hipster culture, but in 1957 it was not explicitly political, due in part to the blacklisting of Pete Seeger and the Weavers in the early 1950s because of their left-wing views. The first breakthrough commercial success of the folk revival was the Kingston Trio's 1958 hit, the apolitical song "Tom Dooley." Other expressions of this cultural rebellion included Malvina Reynold's song, "Little Boxes" (recorded in 1962) and the commentary of comedian Lenny Bruce (whose first album, "The Sick Humor of Lenny Bruce," came out in 1959).

The mainstream media didn't quite know how to deal with these white hipsters. It mostly made fun of them, reflected in the character of Maynard G. Krebs in the popular TV show "Dobie Gillis," which began in 1959. Krebs wore a goatee, played the bongo drums, wore unkempt and unfashionable clothes, and was allergic to work. "Dobie Gillis" was the first network TV show to feature teenagers (i.e. early baby-boomers) as leading characters. (One of the actors, Sheila Kuehl--who played the nerdy Zelda Gilroy--years later became a prominent feminist lawyer and the first open lesbian elected to the California state legislature and became a powerful state Senator and LA County supervisor).

Mailer believed that "The White Negro" displayed sympathy for the plight of Black Americans. To the extent that Black people engaged in anti-social or even criminal behavior, Mailer thought that it was a way to cope with the harsh realities of racism. He was not blaming the victim, but blaming the system. Even so, "The White Negro" includes a number of uncomfortable racist stereotypes, including a line in which Mailer described the "courage" of "two strong eighteen-year-old hoodlums" in beating "in the brains of a candy store owner." (The hoodlums were Black and the store owner white). The essay also includes this embarrassing, and embarrassingly-long, sentence:

"Knowing in the cells of his existence that life was war, nothing but war, the Negro (all exceptions admitted) could rarely afford the sophisticated inhibitions of civilization, and so he kept for his survival the art of the primitive, he lived in the enormous present, he subsisted for his Saturday night kicks, relinquishing the pleasures of the mind for the more obligatory pleasures of the body, and in his music he gave voice to the character and quality of his existence, to his rage and the infinite variations of joy, lust, languor, growl, cramp, pinch, scream and despair of his orgasm."

This section of the essay foreshadows psychiatrist Frantz Fanon's 1961 book, The Wretched of the Earth, about the therapeutic uses of violence to challenge dehumanizing colonialism. Fanon was writing about Third World peasants, but his analysis became popular among some portions of the white American New Left, who viewed the urban riots of the 1960s as a form of political protest and rebellion and who supported militants in the Black community who believed it was necessary to "pick up the gun" to defend themselves against police brutality.

Even many radicals, however, viewed such views as nihilistic and counter-productive. This is one reason why, in his 1984 autobiography A Margin of Hope, Howe expressed second thoughts about publishing Mailer's essay. Howe acknowledged that, at the time, it was a coup for Dissent to have someone of Mailer's fame write for the magazine, and to do so without getting paid. But ultimately Howe concluded that "it had been unprincipled to accept this essay for Dissent."

Mailer's view of the white hipster was ambivalent. Mailer considered himself a socialist and he viewed the psychological alienation and cultural rebellion of white hipsters as too apolitical, a failure of will. Yet Mailer completely ignored the emergence of at least two kinds of political rebellion that were already underway when he wrote his essay. One was the civil rights movement. The bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama, triggered by the refusal of NAACP activist Rosa Parks to move from her seat on a segregated bus, began in December 1955. The boycott lasted a year, forced the city to desegregate the buses, catapulted Martin Luther King to national fame, and catalyzed the modern civil rights movement, including the lunch counter sit-ins and Freedom Rides a few years later. It also mobilized large numbers of white baby-boomers who got involved in the protest movement. It is inconceivable that Mailer failed to mention this.

The other political rebellion was the "ban the bomb" movement, led by pacifists, that engaged in hundreds of acts of civil disobedience around the country (and around the world) to pressure the U.S. government (as well as the Soviet Union) to halt the use of nuclear weapons and nuclear testing. That campaign, which challenged the premises of the Cold War arms race, eventually led President Kennedy and the Soviets to agree to a Limited Nuclear Test Ban treaty on August 5, 1963, three months before JFK was assassinated. The small cadre of pacifists who led the ban-the-bomb movement became the core of the much-larger anti-Vietnam movement a few years later.

Although Mailer failed to mention these burgeoning movements, he recognized that something was happening below-the-surface in society and he tried to describe and explain it. For all its many inexcusable flaws, "The White Negro" was an important essay for its time and a yardstick for measuring how we discuss race today. Fortunately Dissent has kept it on its website, so you don't have to wait for the Mailer anthology from Skyhorse to read it.

A 1957 essay by celebrated writer Norman Mailer called "The White Negro" is getting a lot of renewed attention these days. According to a just-published article by journalist Michael Wolff in a site called The Ankler, Random House decided against publishing a collection of Mailer's essays after a "junior staffer" complained about "The White Negro," which was going to be included in the anthology. According to Wolff, the staffer believed that the title was racist and that was enough for Random House to scuttle the project in order to avoid controversy. This quickly triggered a debate on social media over so-called "cancel culture." Did the nation's largest book publisher cancel the Mailer book over fears of being called racist?

Subsequent reporting revealed that Random House was in discussions with Mailer's family about publishing a collection of his writings in 2023 to celebrate the 100th anniversary of his birth, but that no contract had yet been signed. After Random House nixed the project, Skyhorse--a much smaller publisher that lacks Random House's prestige and marketing capacity--agreed to publish the book

In recent years, Random House--which is owned by Bertelsmann, a huge German company--has "gobbled up" (in Wolff's words) other publishers. A deal to acquire its biggest rival, Simon & Schuster, for $2 billion, is now pending. The federal Justice Department is currently suing the two companies for violating anti-trust laws, concerned about the concentration of ownership in the publishing industry. One shouldn't be surprised that Random House, while in the middle of fighting the Justice Department, didn't want to get ensnared in a controversy over whether one of Mailer's essays is racist.

Since the upsurge of protest following the murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis cop in May 2020, and the adoption of voter suppression laws by states that target Black voters, hundreds of big corporations have issued public statements opposing racism. Unfortunately, few of them have changed their discriminatory business practices and many of them continue to make political contributions to Republican candidates who endorse the white-supremacist policy agenda that opposes voting rights and social programs to lift Americans out of poverty.

It still isn't clear why Random House got cold feet or whether the inclusion of "The White Negro" had anything to do with it. But if the controversy draws attention to that 65-year old essay, it will have served a useful purpose. It was provocative and controversial when it was first published in the Fall 1957 issue of Dissent, a quarterly magazine. It is worth re-reading today not only as a historical artifact but as a way of revealing how discussions of racism have evolved in society in general and on the Left in particular.

Dissent was then a relatively new socialist magazine, having published its first issue in 1954. Starting a socialist magazine in the midst of the Cold War and McCarthyism was a bold move by its editors, literary critic Irving Howe and sociologist Lewis Coser. They published many articles by up-and-coming as well as prominent academics, journalists, novelists, and activists on political, sociological, and literary topics that challenged mainstream orthodoxy and stirred controversy.

The Dissent editors considered it a coup to get a well-known writer like Mailer to publish an essay in their still-obscure magazine. He would become much more famous, and more controversial, in subsequent years. He was not only a respected writer but also a cultural celebrity. He published a dozen novels and 20 nonfiction books as well as screenplays, stage plays, TV miniseries, two books of poetry, collections of short stories, and hundreds of essays and journalistic profiles.

One of his best articles is "Superman Comes to the Supermarket," a long essay published in Esquire magazine in November 1960 about John F. Kennedy, whom Mailer described as an "existential hero" whose election as president could save the country from the boring eight years of Dwight Eisenhower's presidency and the stultifying cultural and political conformity of the 1950s. That article was Mailer's first foray into a new form of on-the-scene political journalism, in which he became a character in the story. He further developed that approach to political reporting in two books--Miami and the Siege of Chicago (about the 1968 Democratic and Republican conventions) and Armies of the Night (about the 1967 protest at the Pentagon), which won the Pulitzer Prize. He also won a Pulitzer for his 1979 crime novel The Executioner's Song, which examines the execution of Gary Gilmore for murder by the state of Utah. This work clearly surpasses his later writings about women, the space program, and boxing.

Mailer was amazingly prolific. He was married six times, had nine children, and had to pay a lot of alimony, so he dashed off many articles and books, resulting in a very uneven track record. He enjoyed being the center of attention. In 1969, he ran unsuccessfully in the Democratic Party primary for New York City mayor on a left-wing agenda, finishing fourth in a field of five. He was a self-promoting, inflammatory, macho bully who once, while drunk at a party, stabbed one of his wives with a knife. He was a frequent guest on TV talk shows. He wore his homophobia on his sleeve. He stirred public battles with other writers, like Gore Vidal, another prominent novelist and polemicist, who was gay. Mailer once punched Vidal at party, knocking him to the floor. Before he got up, Vidal said, "Norman, once again words have failed you."

Mailer became well known for his first novel, The Naked and the Dead, published in 1948, which drew on his experiences as a soldier in World War II. He published two other novels before he began writing journalistic essays for magazines. "The White Negro," was one of his first journalistic pieces.

Let's acknowledge up-front that "The White Negro" is deeply flawed. The essay has some nice turns-of-phrases, but much of it is over-written and some of it is barely readable. Mailer spends too many of its rambling 9,000 words writing about sex and orgies, clearly meant to shock readers. It includes a lot of third-rate psychology--for example, explicating the difference between psychopaths and psychotics. And, as discussed below, it includes some ugly racist stereotypes. My friend Adrian Walker, a Boston Globe columnist, reminded me that James Baldwin wrote an insightful critique of Mailer's essay, which he called, "The Black Boy Looks at the White Boy Norman Mailer," published in Esquire in 1961.

But despite its defects, "The White Negro" tapped into an aspect of American society --the growing alienation of white Americans from the dominant sociological and cultural trends--that few writers at the time had recognized.

The title of Mailer's essay, "The White Negro," can be confusing. It might lead one to assume that it is about middle class Black Americans trying to assimilate into white American culture. That is a topic that the left-wing sociologist Franklin Frazier explored in his scathing book Black Bourgeoisie, initially published in French in 1955 and translated into English two years later, the same year that Mailer's "The White Negro" appeared.

"The White Negro" is mostly about white people, not Black people. It is about the efforts of some white hipsters--mostly bohemians but also radicals--to appropriate (although he didn't use that word) Black culture and style. "Hipster" back then meant something different than it does now. By that word, Mailer meant a growing sense of alienation from and opposition to mainstream white middle class conformist (and increasingly suburban) America. According to Mailer, this was a version of "existentialism"--a philosophical and psychological attempt to cope with the irrationality, violence, and soul-killing destructiveness of post-war America, then only a decade removed from World War II, and the understanding that the Holocaust and concentration camps can happen in so-called advanced societies. The existential stance was also a way of coping with the looming threat of an atomic war (and the air-raid drills that all school kids had to endure), which many Americans believed they had little power to stop.

In "The White Negro," the 34-year old Mailer described the growing unease of some members of his own generation as well as the next generation (the baby boomers) of white Americans. Mailer wrote that Black Americans had to deal with the worst aspects of American society every day, especially violence, poverty, and overt discrimination by cops, employers, banks, the media, and other institutions. By embracing some aspects of Black urban culture--including jazz, marijuana, language, and what would later called "cool"--white hipsters were saying that they didn't buy into the dominant cultural and/or political conformity of the period, including consumerism, suburbanization, the Cold War, TV culture, dull public schools, and large factory-like universities. A few years later, Bob Dylan would echo Mailer's sentiments in his song, "Ballad of a Thin Man," which declared: "Because something is happening here but you don't know what it is. Do you, Mr. Jones?"

According to Mailer, the white hipsters, too, were alienated from the dominant culture. The concept of alienation was gaining currency at the time. Some used the word to explain the rise of "juvenile delinquency," primarily among white youth, which was a topic of much journalistic, academic, and political discussion at the time. It was the subject of the 1953 film "The Wild One" starring Marlon Brando as the leader of a motorcycle gang. (Asked "What are you rebelling against, Johnny?", Brando answers "Whaddaya got?"). Juvenile delinquency was also the focus of two popular 1955 films--"Blackboard Jungle" and "Rebel Without a Cause." In his essay, Mailer referred to the 1944 book Rebel Without A Cause--The Hypnoanalysis of a Criminal Psychopath by Robert Lindner, but not to the film, which made James Dean an idol of the white hipsters Mailer was writing about. (In 1960, the sociologists Richard Cloward and Lloyd Ohlin wrote a book, Delinquency and Opportunity, which argued that low-income and working class youth engage in criminal and semi-criminal activity because they lack the opportunities to succeed in mainstream society, not because they are opposed to mainstream values).

For Mailer, the white "hipster" was a culture rebel, not a criminal. These attitudes were expressed through bohemian (pre-hippie) culture. Mailer was describing a growing mood, but he didn't provide any specific examples, which were all around him, including beat poetry like Allen Ginsberg's Howl (published in 1956), the satirical and anti-establishment MAD magazine (founded in 1952), and Sloan Wilson's novel The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit (published in 1955).

Mailer was certainly familiar with another prominent example--Jack Kerouac's hipster novel On the Road, also published in 1957--which included the author's description of a spending time in the "Denver colored section, wishing I were a Negro, feeling that the best the white world had offered was not enough ecstasy for me, not enough life, joy, kicks, darkness, music, not enough night." Mailer should have given Kerouac some credit for inspiring "The White Negro."

Folk music was also part of the white hipster culture, but in 1957 it was not explicitly political, due in part to the blacklisting of Pete Seeger and the Weavers in the early 1950s because of their left-wing views. The first breakthrough commercial success of the folk revival was the Kingston Trio's 1958 hit, the apolitical song "Tom Dooley." Other expressions of this cultural rebellion included Malvina Reynold's song, "Little Boxes" (recorded in 1962) and the commentary of comedian Lenny Bruce (whose first album, "The Sick Humor of Lenny Bruce," came out in 1959).

The mainstream media didn't quite know how to deal with these white hipsters. It mostly made fun of them, reflected in the character of Maynard G. Krebs in the popular TV show "Dobie Gillis," which began in 1959. Krebs wore a goatee, played the bongo drums, wore unkempt and unfashionable clothes, and was allergic to work. "Dobie Gillis" was the first network TV show to feature teenagers (i.e. early baby-boomers) as leading characters. (One of the actors, Sheila Kuehl--who played the nerdy Zelda Gilroy--years later became a prominent feminist lawyer and the first open lesbian elected to the California state legislature and became a powerful state Senator and LA County supervisor).

Mailer believed that "The White Negro" displayed sympathy for the plight of Black Americans. To the extent that Black people engaged in anti-social or even criminal behavior, Mailer thought that it was a way to cope with the harsh realities of racism. He was not blaming the victim, but blaming the system. Even so, "The White Negro" includes a number of uncomfortable racist stereotypes, including a line in which Mailer described the "courage" of "two strong eighteen-year-old hoodlums" in beating "in the brains of a candy store owner." (The hoodlums were Black and the store owner white). The essay also includes this embarrassing, and embarrassingly-long, sentence:

"Knowing in the cells of his existence that life was war, nothing but war, the Negro (all exceptions admitted) could rarely afford the sophisticated inhibitions of civilization, and so he kept for his survival the art of the primitive, he lived in the enormous present, he subsisted for his Saturday night kicks, relinquishing the pleasures of the mind for the more obligatory pleasures of the body, and in his music he gave voice to the character and quality of his existence, to his rage and the infinite variations of joy, lust, languor, growl, cramp, pinch, scream and despair of his orgasm."

This section of the essay foreshadows psychiatrist Frantz Fanon's 1961 book, The Wretched of the Earth, about the therapeutic uses of violence to challenge dehumanizing colonialism. Fanon was writing about Third World peasants, but his analysis became popular among some portions of the white American New Left, who viewed the urban riots of the 1960s as a form of political protest and rebellion and who supported militants in the Black community who believed it was necessary to "pick up the gun" to defend themselves against police brutality.

Even many radicals, however, viewed such views as nihilistic and counter-productive. This is one reason why, in his 1984 autobiography A Margin of Hope, Howe expressed second thoughts about publishing Mailer's essay. Howe acknowledged that, at the time, it was a coup for Dissent to have someone of Mailer's fame write for the magazine, and to do so without getting paid. But ultimately Howe concluded that "it had been unprincipled to accept this essay for Dissent."

Mailer's view of the white hipster was ambivalent. Mailer considered himself a socialist and he viewed the psychological alienation and cultural rebellion of white hipsters as too apolitical, a failure of will. Yet Mailer completely ignored the emergence of at least two kinds of political rebellion that were already underway when he wrote his essay. One was the civil rights movement. The bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama, triggered by the refusal of NAACP activist Rosa Parks to move from her seat on a segregated bus, began in December 1955. The boycott lasted a year, forced the city to desegregate the buses, catapulted Martin Luther King to national fame, and catalyzed the modern civil rights movement, including the lunch counter sit-ins and Freedom Rides a few years later. It also mobilized large numbers of white baby-boomers who got involved in the protest movement. It is inconceivable that Mailer failed to mention this.

The other political rebellion was the "ban the bomb" movement, led by pacifists, that engaged in hundreds of acts of civil disobedience around the country (and around the world) to pressure the U.S. government (as well as the Soviet Union) to halt the use of nuclear weapons and nuclear testing. That campaign, which challenged the premises of the Cold War arms race, eventually led President Kennedy and the Soviets to agree to a Limited Nuclear Test Ban treaty on August 5, 1963, three months before JFK was assassinated. The small cadre of pacifists who led the ban-the-bomb movement became the core of the much-larger anti-Vietnam movement a few years later.

Although Mailer failed to mention these burgeoning movements, he recognized that something was happening below-the-surface in society and he tried to describe and explain it. For all its many inexcusable flaws, "The White Negro" was an important essay for its time and a yardstick for measuring how we discuss race today. Fortunately Dissent has kept it on its website, so you don't have to wait for the Mailer anthology from Skyhorse to read it.