If neoliberalism was already on life support, then the coronavirus has administered the lethal blow. (Photo: Lan Hongguang/Xinhua News Agency/PA Images)

A Spectre Is Haunting the West-the Spectre of Authoritarian Capitalism

From coronavirus to climate change, China is surging ahead of the US and its allies. Are we witnessing the slow death of liberal capitalism?

Amidst the turmoil in global financial markets in recent weeks, something unusual has happened.

Investors, seeking shelter from the coronavirus-linked sell-off, have piled into Chinese government bonds on an unprecedented scale. These purchases have increased the total foreign ownership of Beijing's bonds to record highs, even as much of the country is still emerging from lockdown after the viral outbreak. In an ironic twist, the country where the pandemic originated has become an unlikely safe haven for investors - a shift that one prominent trader has described as "the single largest change in capital markets in anybody's lifetime."

But it is not only investors that are looking to China. Last month the European Commission president, Ursula von der Leyen, thanked Beijing for delivering more than 2 million masks and 50,000 coronavirus testing kits to European countries including France, Italy, the Netherlands and Poland. Europe is not alone: after successfully bringing the spread of the virus under control domestically (for the time being at least) China has embarked on a high-profile campaign of health diplomacy, winning applause around the world for providing support to countries in need.

Chinese civil society is playing its part too. The Jack Ma Foundation, a charitable organisation led by China's wealthiest individual, has pledged to provide each African nation with 20,000 testing kits, 100,000 masks and 1,000 protective suits.

In the US, things look rather different. President Trump's mishandling of the crisis has put the US on track to experience the most deadly outbreak of any major country. After initially denying the gravity of the pandemic, President Trump quickly turned his fire on Beijing, referring to the disease as the 'Chinese virus'. Meanwhile, the President's allies on both sides of the Atlantic have demanded that China pay reparations for allegedly causing the outbreak.

Despite launching a massive $2 trillion stimulus package to cushion the economic blow from the pandemic, many believe that the US is sleepwalking into a public health catastrophe - one that will be beamed onto TV screens all over the world.

In stark contrast to China's international charm offensive, President Trump has stayed true to his 'America First' philosophy. In March it was reported that Trump had offered international medical companies large sums of money to produce vaccines "only for the United States". At the beginning of April, 200,000 masks that were produced in Singapore by US firm 3M and bound for Germany were confiscated in Bangkok and diverted to the US, an incident that a senior German official described as "modern piracy". The government of Barbados has also accused the United States of "seizing" ventilators that were bound for the country and paid for by singer Rihanna. This week, President Trump announced that the US was halting payments to the World Health Organization (WHO) over its handling of the pandemic, a move that has attracted condemnation from leaders around the world.

Signs of diminishing US soft power are not new. Neither is the adoption of a more assertive stance towards China in Washington - it was Barack Obama, not Donald Trump, that initiated the 'pivot' in American strategy towards China in 2011.

But under Trump's leadership, tensions between the two global powers have escalated, as have Washington's efforts to contain China's rise. Now, the acrimony over the coronavirus pandemic has added fuel to the fire.

At the root of these rising tensions lies a common cause: the emergence of an economic model that has the potential to rival the productive power of Western liberal capitalism - and ultimately threaten the technological supremacy that has long underpinned US hegemony.

China's economic miracle

Last year the People's Republic of China celebrated its 70th anniversary. The occasion marked the victory of Mao Zedong's forces over the Kuomintang-led government of the Republic of China, securing the Communist Party of China's control over the world's most populous nation.

Under Mao's leadership, the country did experience moderate economic expansion, with real GDP per capita growing at an average of 4% between 1952 to 1978. But life was chaotic and often violent, with grand schemes such as the Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution failing to live up to their promise, while also inflicting unnecessary and often brutal suffering on China's rapidly growing population.

In 1978, Deng Xiaoping became China's new paramount leader, after outmanoeuvring Mao's chosen successor, Hua Guofeng. Deng oversaw the country's historic 'Reform and Opening-up' process, which increased the role of market incentives and opened up the Chinese economy to global trade. In the decades since, China's economic transformation has been nothing short of astonishing.

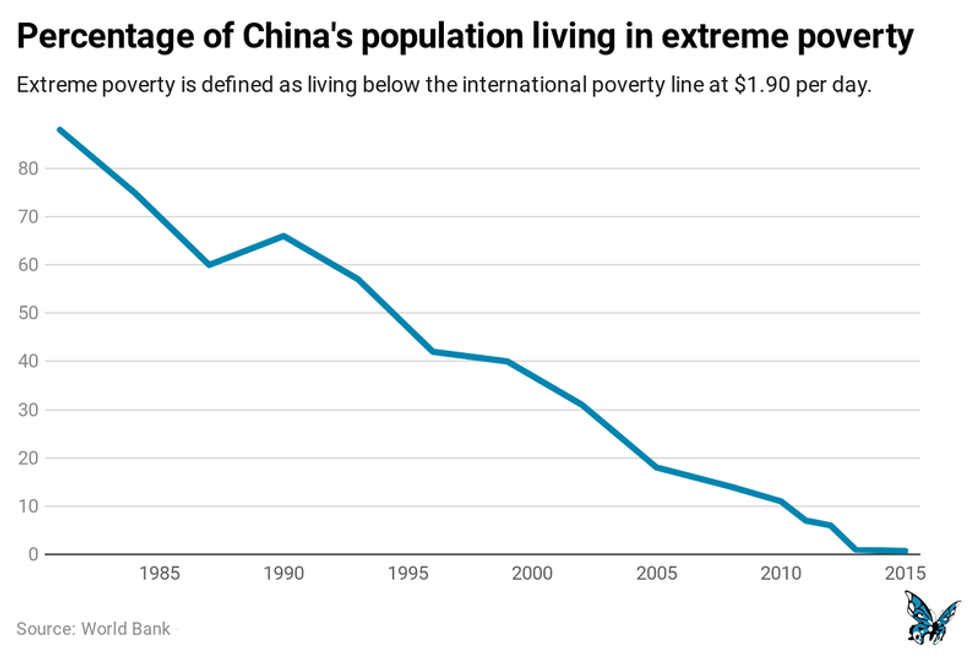

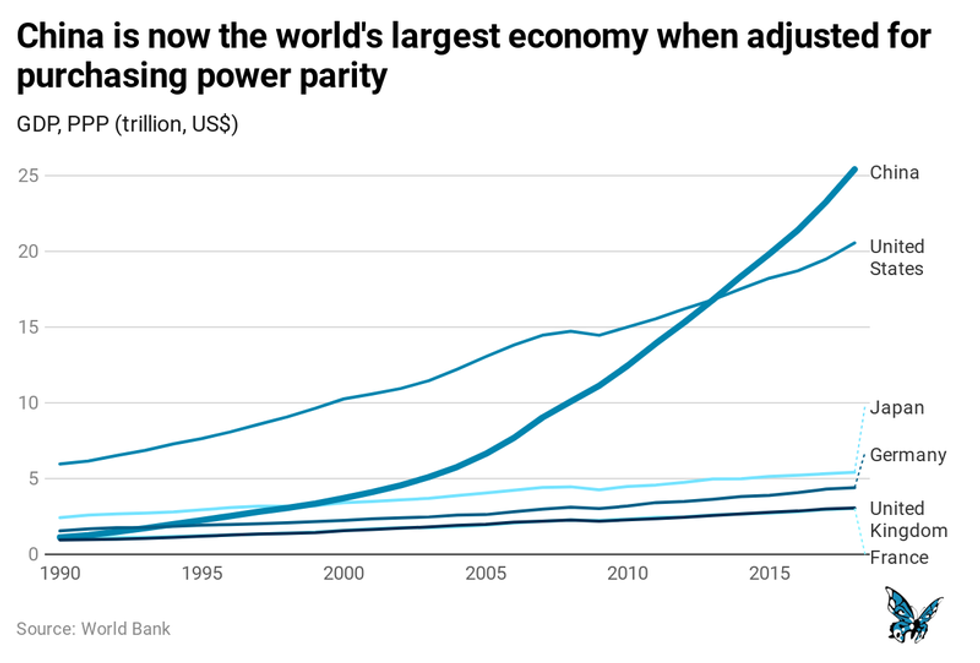

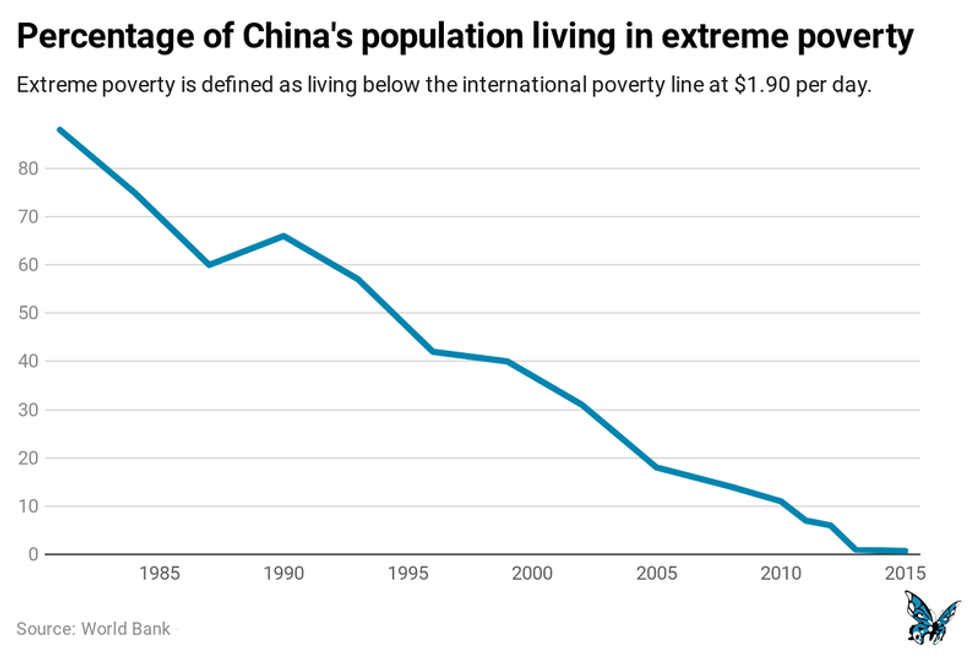

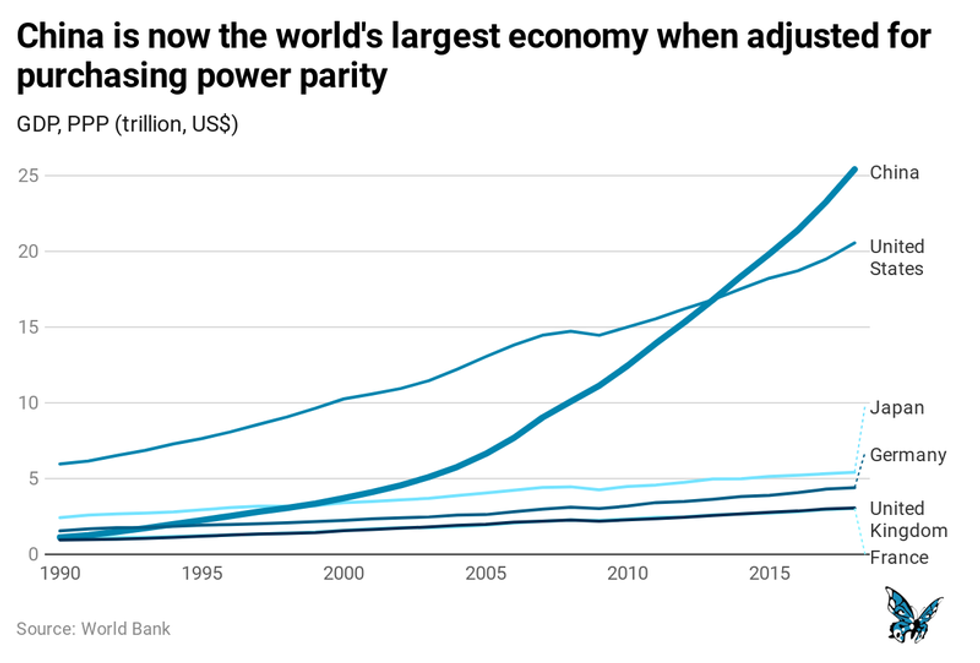

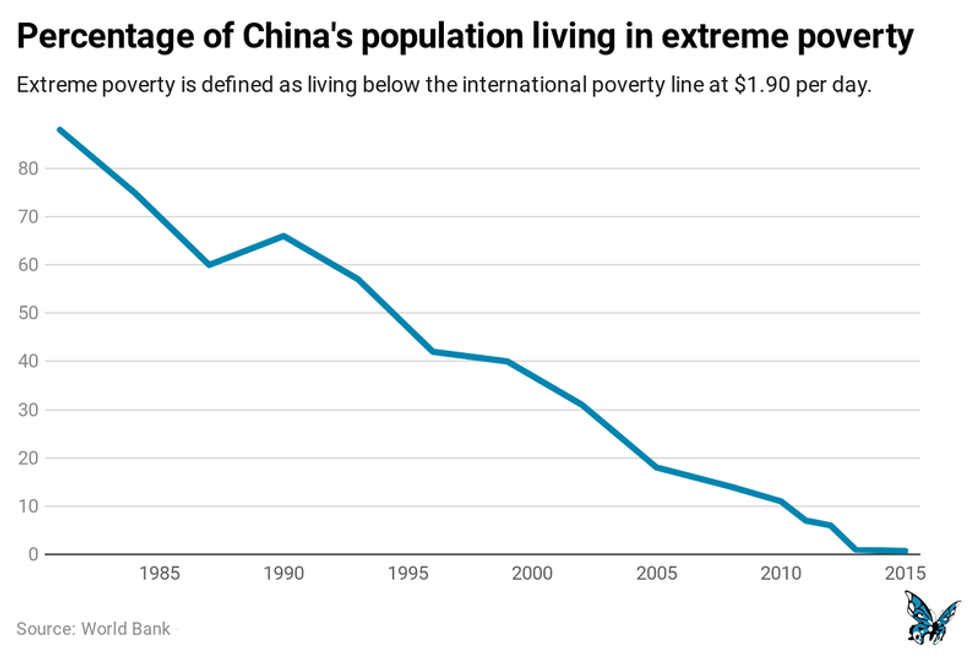

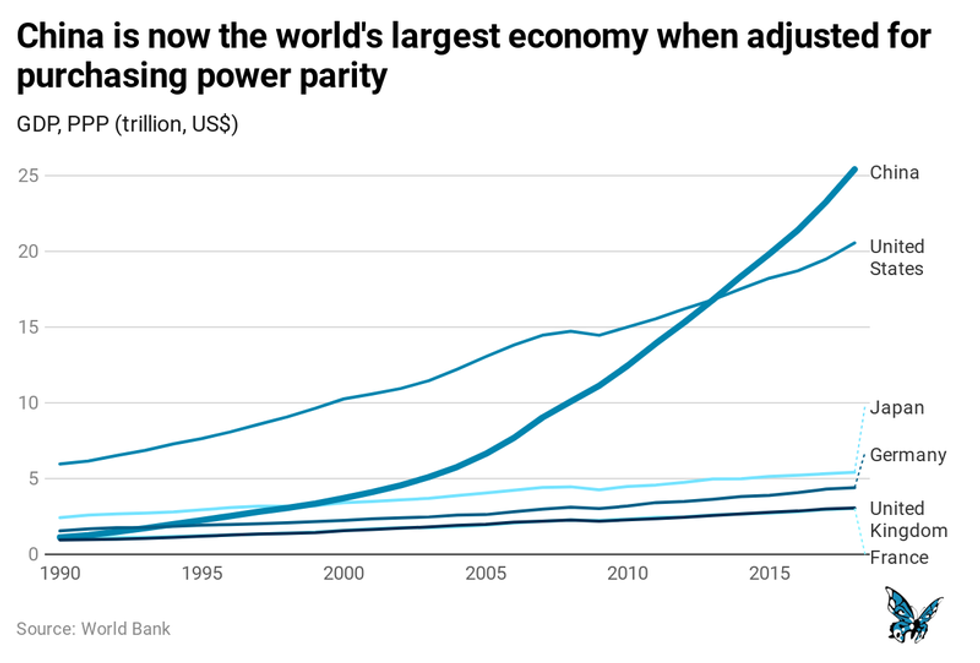

In 1981, 88% of the Chinese population lived in extreme poverty. In the four decades since, nearly a billion people have been lifted out of poverty, leaving the figure at less than 2%. Over the same time period, the size of China's economy increased from $195 billion - around the same size as the Spanish economy - to nearly $14 trillion today. By some measures, China's economy has overtaken the US and is now the largest in the world. China is also home to the second largest number of Fortune 500 companies in the world, and more billionaires than Europe.

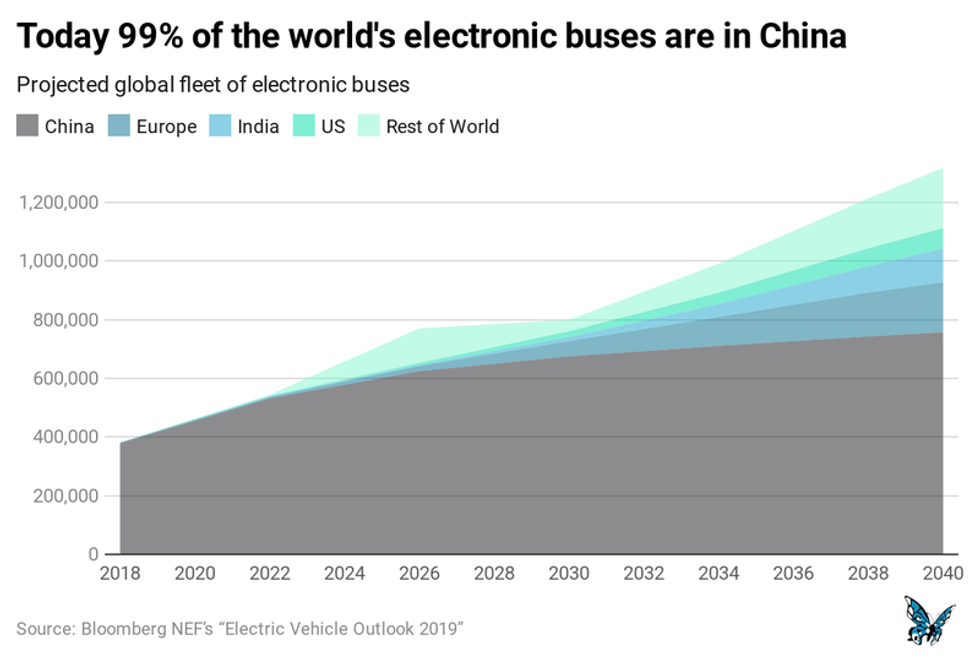

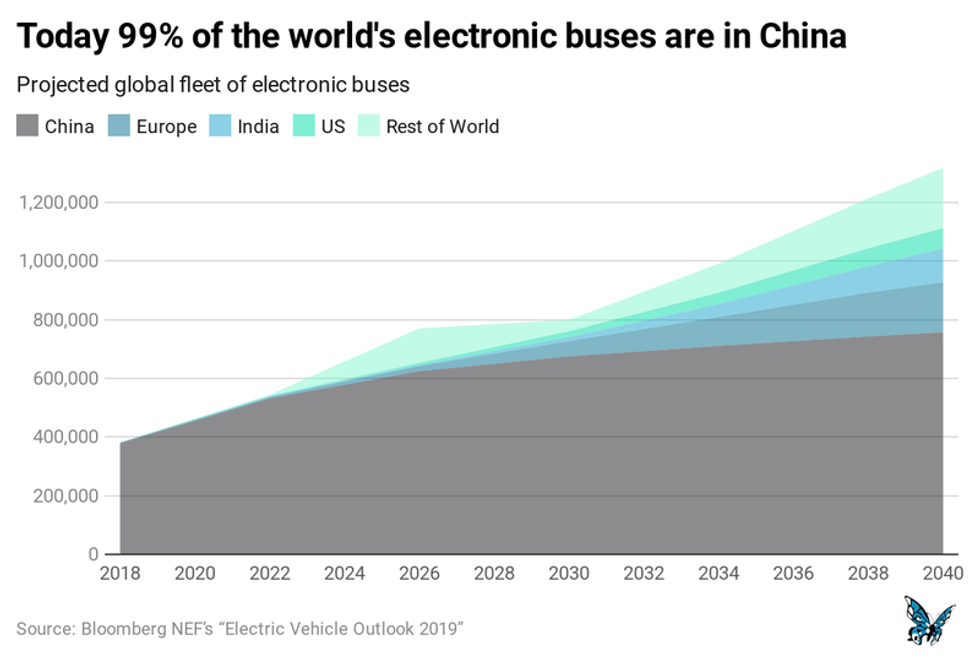

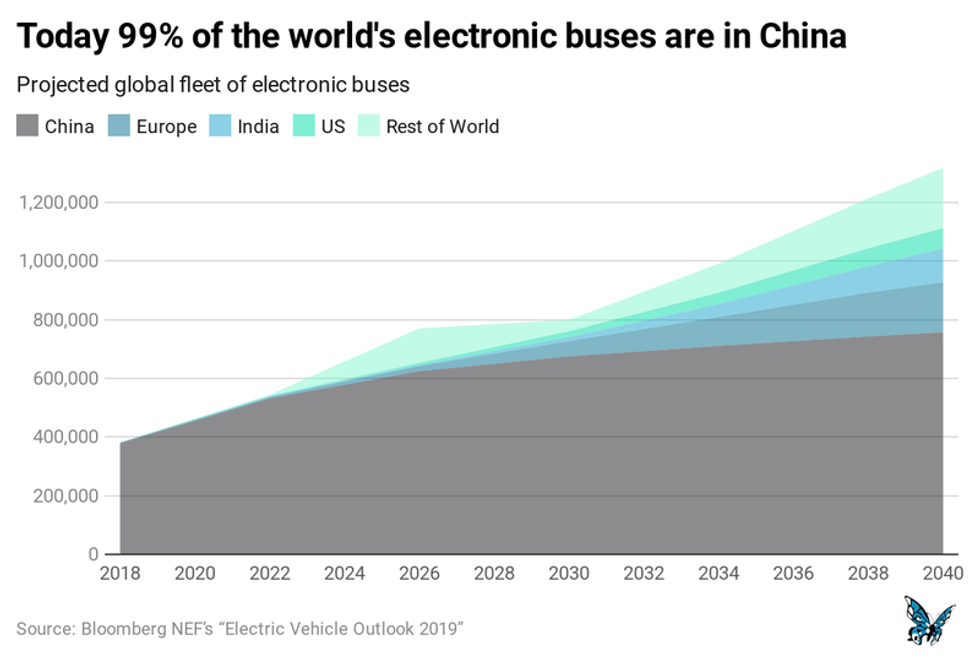

According to the World Bank, China has experienced "the fastest sustained expansion by a major economy in history." But this has not come without costs, particularly to the environment. Since 2006 China has been the largest emitter of CO2, and today it is the world's largest consumer of coal, and the second-largest of oil. But unlike the US, China is taking the challenge of environmental breakdown seriously. In recent years, China has spent more on greening its energy system than America and the European Union combined. China is now the world's leading investor in wind turbines and other renewable energy technologies, and produces more wind turbines and solar panels each year than any other country. Out of the 425,000 electric buses that exist worldwide today, 421,000 are in China - the U.S. accounts for a mere 300.

Under the leadership of Xi Jinping, the Communist Party of China has bold plans for the future. Since taking office in 2012, President Xi has overseen a major crackdown on corruption, and has launched a number of ambitious socio-economic reforms. Foremost among these is the 'Belt and Road Initiative' (sometimes referred to as the New Silk Road) to connect Asia with Europe and Africa in one of the grandest and most disruptive mega projects the world has ever seen.

Xi's ambitions are not limited to planet earth. Under his leadership, the regime has also placed a major emphasis on enhancing China's space capabilities as part of the nation's development strategy, referring to this as China's 'space dream'. A recent white paper setting out China's ambitions in space included plans for a lunar presence, asteroid mining and deep space exploration.

China's remarkable economic transformation has been underpinned by the country's powerful yet distinct economic model. Officially called 'socialism with Chinese characteristics', it combines strategic state ownership and planning with market-oriented incentives and a one-party political system to create a distinct economic model that remains poorly understood in the West.

Whether it is accurate to describe this system as a form of 'socialism' is another matter. Today the private sector accounts for the overwhelming majority output, employment and investment, and there is little sign of democratic workers control. As the economist Branko Milanovic puts it in his recent book, 'Capitalism, Alone':

"To qualify as capitalist, a society should be such as most of its production is conducted using privately owned means of production (capital, land), most workers are wage-labourers (not legally tied to land or working as self-employed using their own capital), and most decisions regarding production and pricing are taken in a decentralised fashion (that is, without anyone imposing them on enterprises). China scores as positively capitalistic on all three accounts."

Despite this, China's economic model is distinct from Western liberal capitalism in a number of key ways. Notably, the state holds a tight grip over the economy through a number of major institutional actors that play a crucial role in the coordination of economic activity.

One prominent example is the State-Owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC), which was formed in 2003 when a number of industry specific ministries were merged. Reporting directly to China's state council, SASAC owns and controls the firms that oversee the commanding industrial heights of the Chinese economy. The companies under its control have combined assets of $26 trillion and revenue of more than $3.6 trillion - more than the GDP of the United Kingdom - making it the largest economic entity in the world.

As Mark Wu, Assistant Professor of Law at Harvard Law School, describes:

"Imagine if one U.S. government agency controlled General Electric, General Motors, Ford, Boeing, U.S. Steel, DuPont, AT&T, Verizon, Honeywell, and United Technologies. Furthermore, imagine this agency were not simply a passive shareholder, but... could hire and fire management, deploy and transfer resources across holding companies, and generate synergies across its holdings."

Even in firms where the state is not the dominant shareholder, the Chinese party-state still has a significant amount of influence. As scholars Curtis J. Milhaupt and Wentong Zheng have highlighted, the boundary between state and private ownership of enterprise is often blurred in contemporary China. One reason for this is the role of the Communist Party in China's economic life. Each organization with more than three Communist Party members must form a Party committee within the organisation, which in many cases has a significant influence over corporate decision making. This requirement extends not only to state-owned enterprises, but also to private companies and foreign-owned firms.

Another key difference is the state's control over the finance sector. China's banking system has more than tripled in size since 2008, and is now the largest in the world. But again, China's banking sector is largely owned and controlled via a state holding company called Central Huijin Investment, which owns major stakes in the "Big Four" commercial banks and the China Development Bank. In turn, Central Huijin is a subsidiary of the China Investment Corporation, China's sovereign wealth fund. Many companies that are not state-owned receive financing on preferential terms from these public banks.

China's central bank, the People's Bank of China, also operates differently to most Western central banks. It uses an array of tools to tightly control interest rates and the amount of money in the Chinese economy, as well as the value of the Chinese renminbi relative to other currencies. Crucially, the People's Bank of China strictly controls the flows of capital in and out of the country. While capital controls have been taboo in the West for many decades, they are a crucial part of China's economic and financial architecture.

This tight control over the financial system allows the state to coordinate economic activity in a way that is not possible in most Western countries, where private finance reigns supreme. It also enables the Chinese state to insulate the domestic economy from the turbulence of global financial markets.

Perhaps the most powerful economic entity is the National Development and Reform Commission which oversees the creation of China's Five-Year Plan, and is responsible for formulating and implementing strategies for national economic and social development. This includes oversight of numerous policy areas including industrial policy, energy policy and price setting for key commodities that are not set by market forces such as electricity, oil, natural gas, and water. In addition, it is responsible for approving all large infrastructure projects and investments, regardless of whether the entity undertaking them is a state-owned enterprise, private company or foreign company.

As Milanovic notes, China's recent rulers have viewed the private sector as akin to a bird in a cage: if it is controlled too tightly, it will, like an imprisoned bird, suffocate; if it is left entirely free, it will fly away.

As China's domestic economy has grown, so has its presence abroad. In recent years Chinese entities have embarked on a vast overseas shopping spree, buying up corporations, real estate and infrastructure all over the world. In Europe alone, Chinese entities now own, or have a stake in, four airports, six maritime ports and 13 professional football teams, including Manchester City, Inter Milan and AC Milan.

Chinese investment into Africa has also soared. Since 2005, the country has pumped over $400 billion in the continent, and is now its largest trading partner, prompting analysts to talk about 'a new scramble for Africa'. Financing for major investment projects has mainly come from two state-owned banks: the Export-Import Bank of China and the China Development Bank. Using what is sometimes characterized as the "Angola Model," low-interest loans are often provided on the condition that natural resources, such as oil or mineral reserves, are used as collateral - a model that has been widely criticised for reinforcing the 'resource curse' that has trapped many African economies in poverty and dictatorship.

Through the Belt and Road Initiative, China aims to significantly expand its economic and political influence throughout Asia, Europe and Africa. To date, more than sixty countries -- accounting for two-thirds of the world's population -- have signed on to projects or indicated an interest in doing so. The investment bank Morgan Stanley has predicted that the cost to China of the initiative over the lifetime of the project could reach $1.2 to 1.3 trillion by 2027, though estimates on total investments vary.

The surveillance state

Ever since the arrival of the internet in China in 1994, authorities have taken steps to strictly monitor and control the flow of information online. In 2010, the government published the white paper 'The Internet In China' which set out its modern policy towards the internet and online activity. The paper outlined the concept of "internet sovereignty" which emphasised China's jurisdiction over web content and providers within Chinese territory. "Laws and regulations clearly prohibit the spread of information that contains content subverting state power, undermining national unity [or] infringing upon national honour and interests," it said.

Since then, the concept of 'internet sovereignty' has gained traction throughout the world and has been adopted by several states looking to control the dissemination of information online including Russia, Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Iran.

Under Xi Jinping's leadership, Chinese authorities have cracked down on subversive speech online and reinforced the so-called 'Great Firewall of China' which forms the bedrock of China's internet policy. At the same time, a rapid increase in the number of CCTV cameras means that the surveillance of online activity is now being extended into the real world. The country's 'Skynet' project, as China's surveillance network is known, plans to have over 400 million surveillance cameras installed across the country by the end of this year.

A recent study found that 8 out of the 10 cities with the most CCTV cameras per 1,000 people are in China, with Chongqing, Shenzhen and Shanghai being the most monitored cities in the world. A growing number of these cameras are powered by facial-recognition and artificial intelligence technologies, allowing authorities to track and monitor the population with a remarkable degree of sophistication.

Although China is expanding its surveillance infrastructure throughout the country, it is in the western province of Xinjiang where it is most prevalent. Human rights groups report that the Chinese government is detaining and surveilling millions of people from the minority Muslim Uighur population on an unprecedented scale. As well as mass surveillance using facial recognition technologies, police have also conducted large scale DNA swabs, iris scans and blood tests in order to build a region-wide biometric database.

"The Xinjiang police used a facial-recognition app on me", Yuan Yang, a correspondent at the Financial Times, reported from the region last year. "When I checked into a hotel, a police officer came to the lobby to register me with her smartphone. She opened up an app and logged into it by scanning her own face. Then she took a photo of my passport profile page from within the app. Finally, the police officer asked to scan my face. Immediately, three women's faces came up on her screen. The top one was an old visa-application photo of mine that I could barely remember having been taken. Clicking through to it showed her my full passport information."

The surveillance state is also integral to the government's plans to roll out a 'Social Credit' system. First described in an official document in 2014, the scheme has already been piloted in various forms in several cities and is expected to become fully operational this year. The system will use big data to track the trustworthiness of everyday citizens, corporations, and government officials and allocate them a score based on past behaviour. Socially desirable behaviour will be rewarded with good credit, while undesirable behaviour will result in sanctions, such as being banned from purchasing plane or train tickets.

On current trends, China is on track to become a surveillance superpower. But it is not the only technology that Beijing has big plans for.

A new technological cold war

For decades many Western economists assumed that China would follow the path of other planned economies: a rapid state-led mobilisation of resources would generate an initial period of strong growth, but this would not last. The theory was that state-led systems were effective at rapidly mobilising capital and labour resources, but they were less effective at increasing productivity - meaning that growth would stall once all the available inputs were being deployed. Growth would be based on "perspiration" not "inspiration", as Paul Krugman famously remarked in 1994, meaning that it could not be sustained.

China's achievements so far have already proven these critics wrong. But it is Beijing's plans for the future that have set alarm bells ringing in Washington. Strategists fear that China's ambitious suite of industrial policies could lead to the US losing technological supremacy in key strategic sectors - along with the economic, military and geopolitical power that comes with it.

The chief offender is the 'Made in China 2025' initiative. Launched in 2015, Made in China 2025 is a ten year plan for China to achieve self-sufficiency in strategic technologies such as advanced information technology, robotics, aerospace, green vehicles and biotechnology. The strategy is reported to be at the very top of President Xi Jinping's economic priorities.

As soon as it was announced, Made in China 2025 alarmed many analysts in Washington. In 2018, the US think tank Council on Foreign Relations described Made in China 2025 as a "real existential threat to U.S. technological leadership." The US Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer has described the initiative as "a very, very serious challenge".

When the Trump administration first imposed higher tariffs on Chinese goods in June 2018, the tariff list mainly focuses on products included in the Made in China 2025 plan, such as IT and robotics related products.

The president's demands in early trade negotiations focused on requiring China to cut state support for high tech industries, stop "forcing" foreign companies to share technology with Chinese enterprises, remove ownership restrictions on incoming investments and - crucially - scrap the Made in China 2025 policy.

In response, the Chinese government started to downplay Made in China 2025, and avoided discussing the initiative publicly. Although there were reports that Beijing abandoned the initiative in late 2018, in practice the change in direction was more cosmetic than real.

In January this year, the US and China signed a long-awaited trade deal. While the deal may have achieved enough to make Donald Trump look tough during his re-election campaign, it has done little to assuage the underlying tensions. The deal includes no provisions on the Made in China 2025 initiative or subsidies for state-owned enterprises. Instead, China has committed to vague pledges not to "support or direct" acquisitions and investment by Chinese companies of foreign technology in "industries targeted by its industrial plans that create distortion." The White House maintains that it will tackle other outstanding issues in a second "phase two" deal in the near future.

From the very beginning, the trade war has been less about trade, and more about constraining Chinese development and preventing China's rise as a rival technological power.

Caught in the crossfire have been companies such as Huawei. Although not a state-owned enterprise, Huawei has received significant support from the Chinese state, including a $30 billion line of credit from the China Development Bank. Thanks in part to this support, Huawei has emerged as the global leader in the development of 5G networks - a technology that is widely expected to be the backbone of the modern digital economy. As a Foreign Policy recently reported: "5G will be the central nervous system of the 21st-century economy -- and if Huawei continues its rise, then Beijing, not Washington, could be best placed to dominate it."

In response to fears over Huawei's dominance, the Trump administration banned the company from acquiring US parts and software and selling its products in the US, and has applied significant diplomatic pressure on allies such as the UK to avoid doing business with Huawei.

The US government's motivation is clear: to crush one of the first Chinese tech companies to become globally competitive, and prevent it from gaining a dominant position in a key technology of the future. Huawei may be the first major company to be in the firing line, but it is unlikely to be the last.

It's not just Uncle Sam that is tightening the screw on China - the tech titans of Silicon Valley have also become increasingly concerned about China's rise.

In a speech in December last year, Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos warned American military leaders that the US risks losing its superiority in key technologies to China - an advantage which has long been the bedrock of the country's military might.

Speaking at the Reagan National Defense Forum, the world's wealthiest individual said: "Do you really want to plan for a future where you have to fight with someone who is as good as you are? This is not a sporting competition. You don't want to fight fair."

To a delighted audience, Bezos said that America's data giants had a duty to make their technology available to the Pentagon to ensure that "freedom and democracy" are preserved. While the kingpins of Silicon Valley once viewed China as the next big market to be exploited, they now increasingly view it as a systemic threat to be contained.

You don't want to fight fair.-Jeff Bezos, CEO and president of Amazon

The coronavirus pandemic has only heightened these tensions further. It was recently reported that the Trump administration is considering tightening rules to prevent Chinese companies from purchasing goods containing advanced US technology such as optical materials, radar equipment and semiconductors. In practice however, such measures are only likely to stiffen Beijing's resolve to become self-sufficient in the development of key technologies.

These rising tensions point to the emergence of a new technological cold war. In the not-too-distant future, we may find ourselves in a world where countries may be able to use US technology or Chinese technology - but not both.

The end of the American century?

China's rise has led some to speculate that we are witnessing the 'end of the American century'. However, until recently there have always been persuasive reasons to believe that such premonitions were premature.

In April last year, the historian Adam Tooze noted that: "As of today, it is a gross exaggeration to talk of an end to the American world order. The two pillars of its global power - military and financial - are still firmly in place. What has ended is any claim on the part of American democracy to provide a political model."

As Tooze and others have documented, the global financial crisis only served to reinforce the global economy's reliance on the dollar. As global banks became increasingly desperate for dollar liquidity, the Federal Reserve transformed itself into a global lender of last resort by establishing dollar swap lines with other central banks. These swap lines provided dollars to foreign central banks in exchange for the local currency, with a promise to swap back once the crisis period had subsided.

Partly as a result of this action, today the global financial system is more dependent on the dollar than ever before, and the dollar remains the world's pre-eminent global reserve currency. With this power comes great privilege: the US can punish any company or country it doesn't like by issuing sanctions which exclude them from the dollar system, and by extension the world economy. At the same time, the US still spends more on defence than the next ten largest countries combined, and the multilateral order is still shaped around American interests.

But some believe that the coronavirus pandemic could represent a pivotal turning point in the balance of power between West and East. Carl Bildt, the former Swedish Prime Minister, recently described the pandemic as "the first great crisis of the post-American world", pointing to the absence of US leadership on the world stage. The evident decay in the quality of US governance and Washington's eschewing of multilateral cooperation is certainly not going unnoticed among world leaders. As the Financial Times's Martin Wolf recently commented: "A government at war with science and its own machinery is now very visible to all."

This is the first great crisis of the post-American world.-Carl Bildt, former Swedish Prime Minister

But there is one place where US leadership is quietly working on overdrive: the Federal Reserve. While investors have sought refuge in Chinese government bonds to a greater extent than ever before, they have also scrambled to buy dollars and US Treasury bonds - the world's traditional 'safe haven' assets.

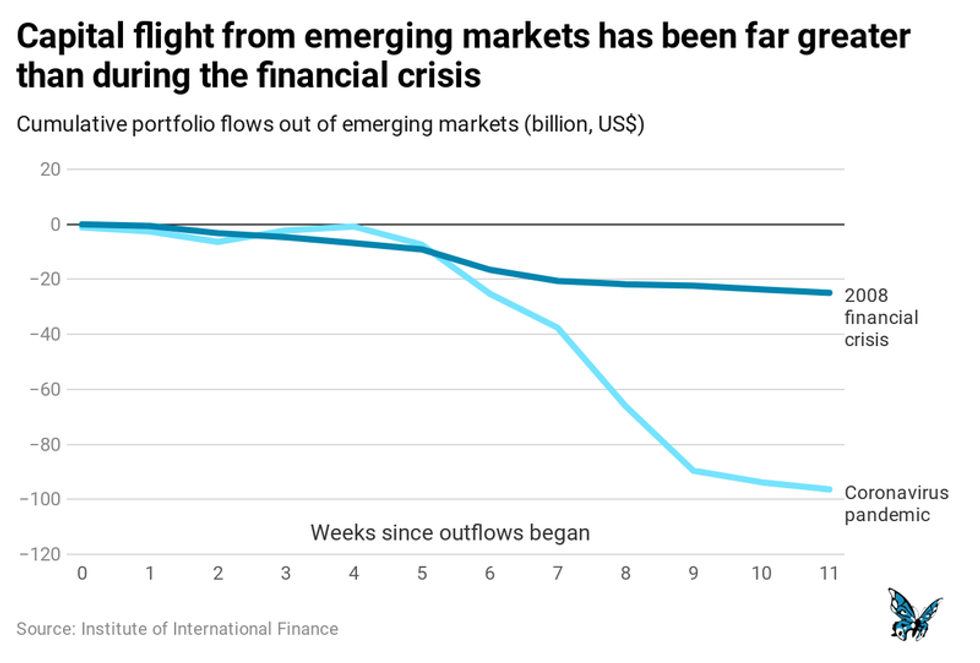

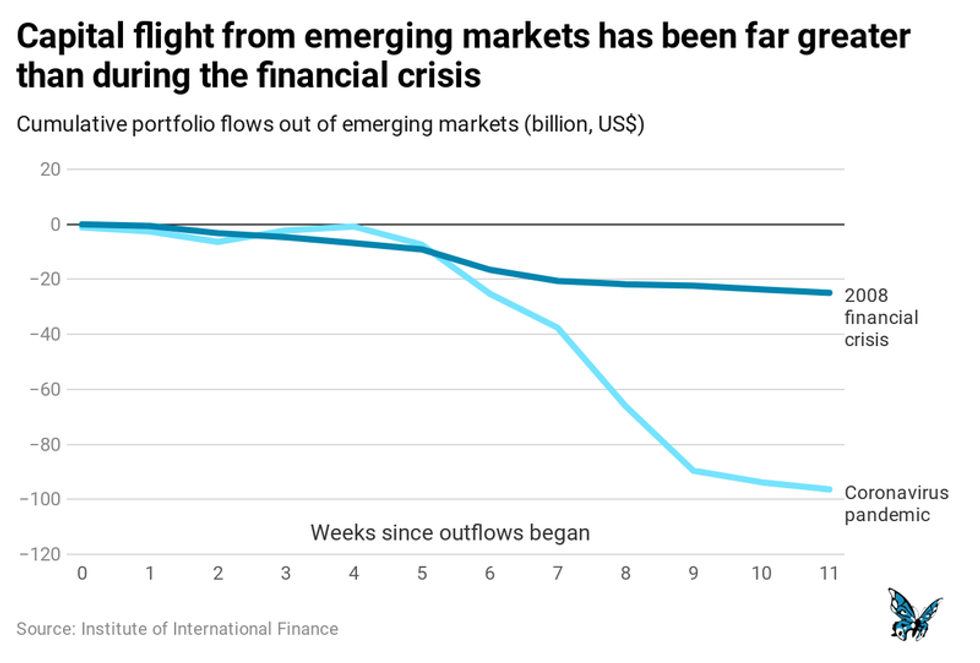

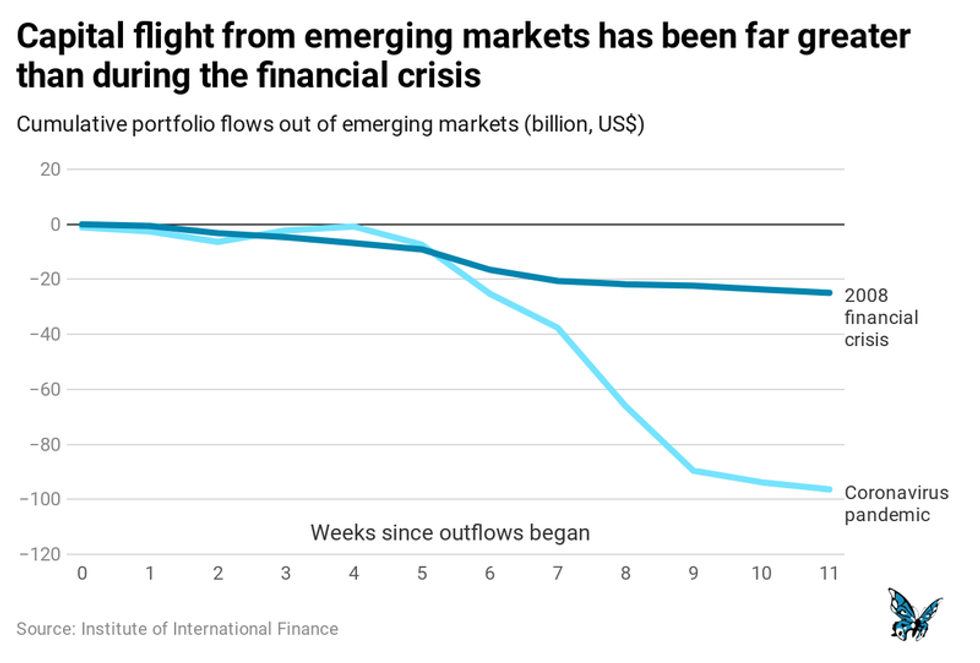

Since January, around $96 billion has flowed out of emerging markets, according to data from the Institute for International Finance. This is more than triple the $26 billion outflow during the financial crisis of a decade ago. This "sudden stop" in dollar funding has caused currencies to plummet and borrowing costs to rise in many developing countries. Combined with a collapse in commodity prices and fragile healthcare systems, this has left many countries dangerously exposed to the pandemic.

This rush to safety has also created a global shortage of dollars which, if allowed to continue, could leave many countries unable to obtain the currency they need to meet their dollar denominated liabilities. As in 2008, the Fed has responded aggressively by reopening swap lines, including to selected emerging market economies such as Mexico and Brazil. It has also gone further by introducing a repurchase agreement facility for foreign central banks. In doing so, it has once again demonstrated its unparalleled power and reach - and exposed the global financial system's deep reliance on the dollar.

But there is one major central bank that does not have an arrangement in place to access dollars at the Federal Reserve: the People's Bank of China. Given the frosty relations between the two powers, this is perhaps unsurprising. But this blockage in the global financial plumbing could have significant consequences.

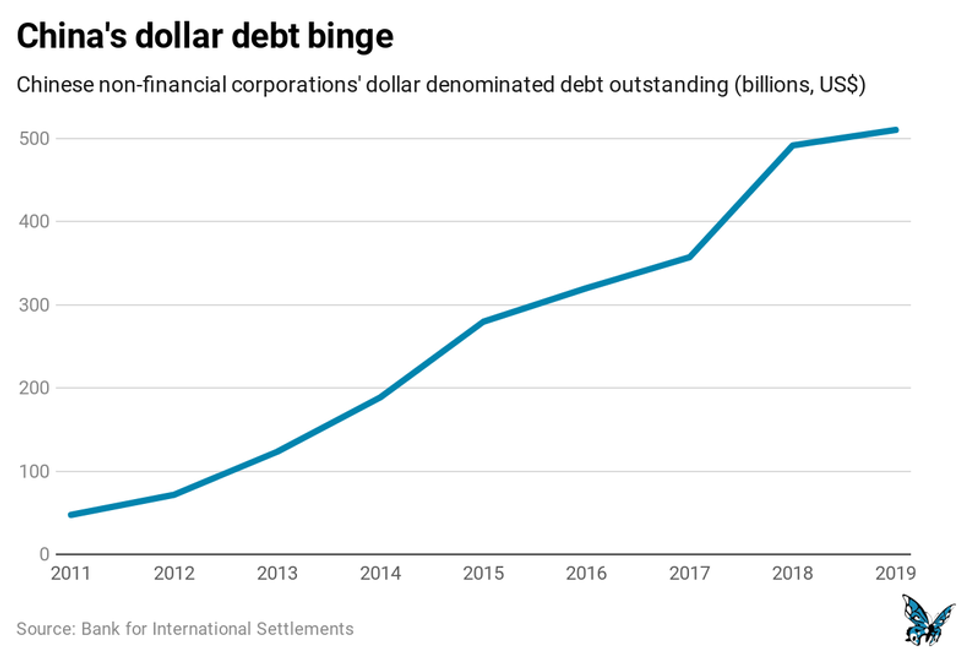

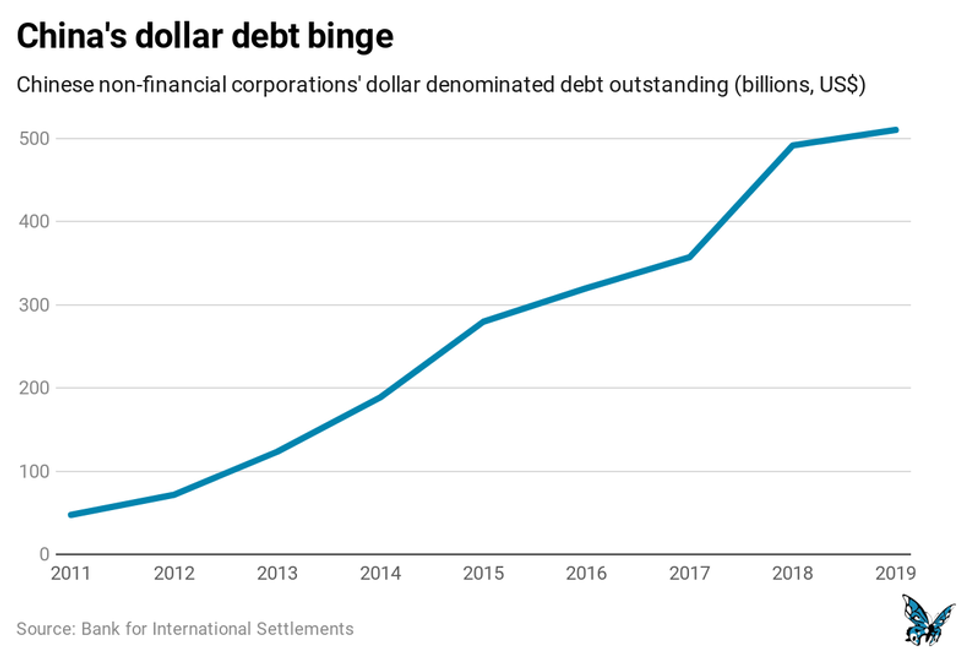

In recent years Chinese businesses have amassed large debts denominated in dollars. Crucially, many of the sectors hardest hit by the coronavirus outbreak, such as airlines and real-estate development, are also among the most likely to have high dollar-denominated debt burdens. If these companies find themselves in difficulty, it could spark a scramble for dollar funding in China. Without access to a dollar swap line, the People's Bank of China may be forced to play its trump card.

The prospect of China suddenly deciding to sell its vast $1 trillion holding of US Treasury bonds has haunted markets for over a decade. Up until now, it has not been in China's interests to try and destabilise the dollar based global financial system. But some believe that the rising tensions from the coronavirus pandemic, combined with the erosion of US soft power, could mean that things are about to change.

Benjamin Braun, a political economist at the Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies, notes that it would be naive to assume that China is content to live under dollar dominance forever. "The question is not whether China would like to wean itself off its dollar dependency, but whether its leaders can do so without causing harm to the Chinese economy", Braun notes. While the future is inherently unpredictable, Braun believes there are a number of variables that could change the political calculus in Beijing.

One of these is if the People's Bank of China is forced to start selling its vast stock of Treasury bonds, which experts including Credit Suisse's Zoltan Pozsar believe is no longer inconceivable. Flooding the market with US Treasury bonds would be akin to setting off a financial nuclear bomb, causing bond yields to spike and wreaking havoc in financial markets, while also undermining the ability of the Federal Reserve to control monetary policy. Such instability could end up generating blowback that would harm China's economy, so most analysts believe that a rapid fire sale is unlikely. However, even a controlled sell-off would likely cause a major headache for Washington, and push the relationship between the White House and Beijing into unchartered waters.

Such a move would satisfy hawks in China, who have long argued that China should cut holdings of dollar-denominated assets and instead seek to strengthen the international standing of the renminbi. Xiao Gang, the former chairman of the China Securities Regulatory Commission, has accused the US of "turning on the dollar printing machine" and misusing its "dollar hegemony to pass its own crisis to the rest of the world".

Braun notes that China has already built the foundations for a renminbi trade area in the form of the Belt and Road project. And if Chinese leaders believe they can achieve their goal of achieving supremacy in key strategic technologies, the need to accumulate dollars may eventually wane. "When China starts to sell its advanced products to the rest of the world, will they want to be paid in dollars? Or will there come a point when they want to be paid in renminbi?", Braun asks.

There are also other long term trends that could reduce the dollar's importance in the global financial system. One is decarbonisation: one of the dollar's key strengths is that it is the currency of the global oil trade. But as countries increasingly switch away from fossil fuels towards clean energy, global demand for dollars will likely decline as countries source their energy from more local sources.

"The global trend towards decarbonisation definitely increases opportunity for non-dollar denominated trade relationships", explains Braun.

Whether the renminbi can challenge the dollar in practice is another matter, however. Daniela Gabor, a professor of economics and macrofinance at UWE Bristol, points out that China has been developing the architecture to promote the internationalisation of the renminbi for many years, but faces a recurring problem: becoming a global reserve currency would necessarily involve opening up China's tightly controlled financial system to the rest of the world. "In practice, China would need to reorganise its financial system so that it resembles something that looks more like the US financial system", Gabor explains. So far, this is a risk that Chinese leaders have not been willing to take.

What a post-dollar global financial architecture would look like remains to be seen. Some believe we could witness a gradual shift from a unilateral order to a multilateral one, with multiple reserve currencies including the dollar, renminbi and, potentially, the euro. Mark Carney, the former governor of the Bank of England, has advocated a global digital currency to supersede the dollar, noting that it would be a mistake to switch one dominant currency for another.

Others believe that Special Drawing Rights, a little-known global quasi-currency run by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), could also play a key role. But while technically plausible, any system mediated through the existing multilateral order is likely to run into political difficulties. "The IMF ultimately serves the interests of the US, so it's difficult to see how it can become an impartial global coordinating mechanism", notes Gabor.

The US, which remains the IMF's largest shareholder, is already blocking efforts to create additional Special Drawing Rights to help low-income emerging economies cope with the coronavirus pandemic - a proposal that has widespread international support including from German chancellor Angela Merkel and French president Emmanuel Macron.

For the time being, what a new system could look like remains a hypothetical question. While few believe the end of dollar supremacy is on the immediate horizon, what matters is that for the first time in over half a century, it is now seriously and openly being discussed.

Europe's dilemma

Leaders in Europe have also been grappling with China's rise. For many years, China's booming economy enabled European consumers to buy cheap imported consumer goods, while European manufacturers exported their expensive cars and capital equipment.

But as Chinese companies have become more competitive higher up the supply chain, some European countries - notably Germany and France - have become worried that China will soon eat into their own advanced manufacturing bases.

As in the US, European leaders have been irked by China's interventionist industrial policies, which many believe have given Chinese firms an unfair advantage. The rules of the EU single market do not permit such interventionist policies on the basis that they distort market competition, meaning that European countries are unable to respond with similar policies, even if they wanted to.

Some now believe that this needs to change. In February last year, the economy ministers of France and Germany published a joint policy manifesto for a European industrial policy that is "fit for the 21st century". The paper states that the EU's competition rules "need to be revised to be able to adequately take into account industrial policy considerations in order to enable European companies to successfully compete on the world stage." It also calls for reforms to EU state aid rules, including "potential involvement of public actors in specific sectors at particular points in time to ensure their long term successful development."

These efforts were bolstered in February this year when the economy ministers of Germany, France, Italy and Poland sent a letter to the EU competition commissioner Margrethe Vestager asking for a review of EU competition policy. They requested that the European Commission "introduce more justified and reasonable flexibility" to its decisions about mergers between European companies, to "take better account of third countries' state intervention". This week, Vestager responded by stating that European countries should consider buying stakes in domestic companies to stave off the threat of Chinese takeovers, and announced that new proposals to deal with unfair competition from foreign state-owned enterprises will be released in June.

What these proposals will look like remains to be seen. But for the time being, the coronavirus pandemic has forced the spotlight onto another area of the EU's incomplete architecture - the Eurozone.

The outbreak has once again revealed the fault lines between the bloc's North-South divide. The global financial crisis exposed the dangers of creating a monetary union without a fiscal union, which countries like Greece, Italy, Ireland and Spain paid the price for in the form of brutal austerity. Although the financial crisis exposed deep flaws in the architecture of the Eurozone, these were never satisfactorily resolved. Instead, a patchwork of mechanisms were introduced which managed to hold the bloc together, while the most difficult questions were deferred to a later date. Thanks to the coronavirus, this date has arrived much sooner than Europe's leaders would have liked.

Countries in Southern Europe, led by France, Spain, and Italy, have called for a common European economic response to the crisis. Key to their demands is the issuance of 'eurobonds' - a common debt instrument issued by a European institution to raise funds for all member states. In practice this would mean mutualising risk across the currency bloc, enabling all member states to borrow funds on the same terms to fight the crisis.

Eurobonds would not only help poorer European states respond to the pandemic, but according to Braun they would also be an essential step towards turning the euro into a genuine global currency capable of competing against the dollar and the renminbi:

"Wedged between an increasingly nationalist dollar area and an authoritarian renminbi area, the costs of not seeking greater monetary power may be rising for Europe. A first step to addressing this would be issuing eurobonds to create a highly liquid market of safe euro assets."

So far however, Eurobonds have been met with fierce resistance from the Eurozone's "frugal four" - Germany, the Netherlands, Austria and Finland - who balk at the idea of underwriting the expenditure of their southern neighbours. This lack of solidarity has generated a furious backlash across the continent, which polls indicate is already fuelling a surge in Euroscepticism. According to the most recent polling, support for remaining in the EU has fallen by 20% in Italy, to 51%.

For Europe, the question of whether it has the clout to compete with the US and China on the world stage is therefore political, not technical. As long as Europe remains hamstrung by a financial and economic architecture that is hard wired to constrain economic dynamism and fuel social discontent, it will find it increasingly squeezed between its more powerful neighbours.

As Gabor notes: "For Europe today, the real question is not whether the euro can challenge the dollar, but whether it can even survive".

The death of neoliberalism

The global financial crisis laid bare the underlying weaknesses of the neoliberal form of capitalism that has dominated policymaking in the West since the 1980s. But without a clear alternative to take its place, the response was to double down on a broken model. The impact of the crisis, and the austerity policies that followed, fractured the political argument in many countries, and contributed to a series of political earthquakes including Brexit, the election of Donald Trump, and the rise of nativist parties across Europe and beyond.

At the same time, the economics profession has entered a period of intellectual upheaval. Stagnant living standards, sharply rising inequality and environmental breakdown have led growing numbers of economists and commentators - including those in mainstream institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) - to acknowledge the shortcomings of free-market orthodoxy.

If neoliberalism was already on life support, then the coronavirus has administered the lethal blow. The pandemic has laid bare the disastrous consequences of decades of privatisation, deregulation and outsourcing in countries like the US and UK, and highlighted the critical importance of strong public services and a well-resourced state bureaucracy. In order to contain the economic fallout from the pandemic, Western countries have ripped up the neoliberal playbook. Market forces have been shunned in favour of economic planning, industrial policy and regulatory controls. Even the IMF, for decades the standard bearer of neoliberal orthodoxy, has floated policy responses that have more in common with the Chinese model of capitalism. In a recent blog, four senior researchers wrote that: "If the crisis worsens, one could imagine the establishment or expansion of large state holding companies to take over distressed private firms."

But those who have spent years dreaming about a world beyond neoliberalism should think twice before popping the champagne. While some may celebrate the arrival of policies that, on the surface at least, involve a greater role for the state in the economy, there remains one problem: there is no evidence that state action inherently leads to progressive social outcomes.

If the crisis worsens, one could imagine the establishment or expansion of large state holding companies to take over distressed private firms.-IMF blog, 1 April 2020

China is a clear case in point. Income inequality is among the highest in the world, labour rights are notoriously weak, and freedom of speech is often brutally suppressed. Speculative dynamics have created vast real estate bubbles and an explosion in private sector debt which many believe could trigger a severe crisis. Workers do not have freedom of association to form trade unions, and non-governmental labour organisations are closely monitored by the state who carry out regular crackdowns.

While Western capitalism is unlikely to turn Chinese anytime soon, it would be naive to assume that the state stepping in to play a greater role in the economy is necessarily going to push politics in a progressive direction. As Christine Berry writes:

"The question is not simply whether states are intervening to manage the crisis, but how. Who wins and who loses from these interventions? Who is being asked to take the pain, and who is being protected? What shape of economy will we be left with when all this is over?"

This goes beyond the economic sphere. Many leaders are already using the coronavirus crisis to ramp up intrusive surveillance and roll back democracy, often taking inspiration from China. Hungary's Prime Minister Viktor Orban has won new dictatorial powers to indefinitely ignore laws and suspend elections. In Israel, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu enacted an emergency decree preventing parliament from convening, in what has been described as a "corona-coup." In Moscow, a network of 100,000 facial recognition cameras are being used to make sure anyone placed under quarantine stays off the streets.

But it is not just strongmen leaders who are exploiting the crisis to tighten their own grip over society. Last week Google and Apple announced that they were jointly developing a global tracking "platform" that will be built into the operating system of every Android and Apple phone, turning virtually every mobile phone into a coronavirus tracker. Many Western governments are now working in partnership with them to scale up national surveillance tools. In the UK, Google and Apple are working with the National Health Service (NHS) to develop a mobile phone app that will trace people's movement and identify whether they have come into contact with infected people. The US, Germany, Italy and the Czech Republic are also reported to be developing their own tools. Thanks to the coronavirus, China's surveillance architecture could arrive in the West much sooner than we think.

Once surveillance measures are introduced, it is likely that they will be extremely difficult to unwind. "The relationship between the citizen and the state here in the West will never be the same again after the Pandemic," Paran Chandrasekaran, Chief Executive of Scentrics, a privacy focused software developer, recently told The Times. "There will be increased surveillance. For decades to come, there will be new thoughts on privacy - possibly even the state having wide-ranging and sweeping powers to see data that might pose a threat to national security."

The relationship between the citizen and the state here in the West will never be the same again after the Pandemic.-Paran Chandrasekaran, Chief Executive of Scentrics

For progressives across the West, the task ahead is enormous. Not only is there a need to respond to the growing dynamism of China's authoritarian political-economic system, there is a need to do so in a way that strengthens democracy and protects civil liberties at a time when both are increasingly under threat. When economies eventually open up again, the urgency of the climate crisis means that we cannot afford to return to business as usual. Patterns of production, distribution and consumption must rapidly be decarbonised, and our environmental footprint must be brought within sustainable limits. And all of this must be done in a way that reduces rather than exacerbates existing inequalities.

What such an agenda looks like, and whether it is politically possible, remains to be seen. In recent years there has been an outburst of progressive new economic thinking on both sides of the Atlantic that aims to combine the aims of social justice at home and abroad, democratic participation and environmental sustainability. While elements of this agenda - from the Green New Deal to expanding democratic forms of ownership - have been embraced by politicians such as Bernie Sanders in the US and Jeremy Corbyn in the UK, it is now clear that neither will take these ideas into power. But for much of the millennial generation whose adult lives have been defined by the financial crisis, climate change and now the coronavirus pandemic, their agendas are now viewed as the minimum baseline for a much bigger transformation of our economic and political systems. Among much of this generation, capitalism - in both its liberal or authoritarian variants - is increasingly viewed as the problem. Socialism, of a new democratic and green variety, is increasingly viewed as the solution.

Following the global financial crisis however, it was the authoritarian right, not the progressive left, that managed to gain a foothold in many countries. The same can be said of the Great Depression in the 1930s. As governments struggle to deal with an economic crisis on a scale that could easily surpass both, there are signs that authoritarian forces could stand to benefit once again.

In 1848 Karl Marx wrote that 'A spectre is haunting Europe -- the spectre of communism.' Today another spectre is haunting the West: its name is authoritarian capitalism.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Amidst the turmoil in global financial markets in recent weeks, something unusual has happened.

Investors, seeking shelter from the coronavirus-linked sell-off, have piled into Chinese government bonds on an unprecedented scale. These purchases have increased the total foreign ownership of Beijing's bonds to record highs, even as much of the country is still emerging from lockdown after the viral outbreak. In an ironic twist, the country where the pandemic originated has become an unlikely safe haven for investors - a shift that one prominent trader has described as "the single largest change in capital markets in anybody's lifetime."

But it is not only investors that are looking to China. Last month the European Commission president, Ursula von der Leyen, thanked Beijing for delivering more than 2 million masks and 50,000 coronavirus testing kits to European countries including France, Italy, the Netherlands and Poland. Europe is not alone: after successfully bringing the spread of the virus under control domestically (for the time being at least) China has embarked on a high-profile campaign of health diplomacy, winning applause around the world for providing support to countries in need.

Chinese civil society is playing its part too. The Jack Ma Foundation, a charitable organisation led by China's wealthiest individual, has pledged to provide each African nation with 20,000 testing kits, 100,000 masks and 1,000 protective suits.

In the US, things look rather different. President Trump's mishandling of the crisis has put the US on track to experience the most deadly outbreak of any major country. After initially denying the gravity of the pandemic, President Trump quickly turned his fire on Beijing, referring to the disease as the 'Chinese virus'. Meanwhile, the President's allies on both sides of the Atlantic have demanded that China pay reparations for allegedly causing the outbreak.

Despite launching a massive $2 trillion stimulus package to cushion the economic blow from the pandemic, many believe that the US is sleepwalking into a public health catastrophe - one that will be beamed onto TV screens all over the world.

In stark contrast to China's international charm offensive, President Trump has stayed true to his 'America First' philosophy. In March it was reported that Trump had offered international medical companies large sums of money to produce vaccines "only for the United States". At the beginning of April, 200,000 masks that were produced in Singapore by US firm 3M and bound for Germany were confiscated in Bangkok and diverted to the US, an incident that a senior German official described as "modern piracy". The government of Barbados has also accused the United States of "seizing" ventilators that were bound for the country and paid for by singer Rihanna. This week, President Trump announced that the US was halting payments to the World Health Organization (WHO) over its handling of the pandemic, a move that has attracted condemnation from leaders around the world.

Signs of diminishing US soft power are not new. Neither is the adoption of a more assertive stance towards China in Washington - it was Barack Obama, not Donald Trump, that initiated the 'pivot' in American strategy towards China in 2011.

But under Trump's leadership, tensions between the two global powers have escalated, as have Washington's efforts to contain China's rise. Now, the acrimony over the coronavirus pandemic has added fuel to the fire.

At the root of these rising tensions lies a common cause: the emergence of an economic model that has the potential to rival the productive power of Western liberal capitalism - and ultimately threaten the technological supremacy that has long underpinned US hegemony.

China's economic miracle

Last year the People's Republic of China celebrated its 70th anniversary. The occasion marked the victory of Mao Zedong's forces over the Kuomintang-led government of the Republic of China, securing the Communist Party of China's control over the world's most populous nation.

Under Mao's leadership, the country did experience moderate economic expansion, with real GDP per capita growing at an average of 4% between 1952 to 1978. But life was chaotic and often violent, with grand schemes such as the Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution failing to live up to their promise, while also inflicting unnecessary and often brutal suffering on China's rapidly growing population.

In 1978, Deng Xiaoping became China's new paramount leader, after outmanoeuvring Mao's chosen successor, Hua Guofeng. Deng oversaw the country's historic 'Reform and Opening-up' process, which increased the role of market incentives and opened up the Chinese economy to global trade. In the decades since, China's economic transformation has been nothing short of astonishing.

In 1981, 88% of the Chinese population lived in extreme poverty. In the four decades since, nearly a billion people have been lifted out of poverty, leaving the figure at less than 2%. Over the same time period, the size of China's economy increased from $195 billion - around the same size as the Spanish economy - to nearly $14 trillion today. By some measures, China's economy has overtaken the US and is now the largest in the world. China is also home to the second largest number of Fortune 500 companies in the world, and more billionaires than Europe.

According to the World Bank, China has experienced "the fastest sustained expansion by a major economy in history." But this has not come without costs, particularly to the environment. Since 2006 China has been the largest emitter of CO2, and today it is the world's largest consumer of coal, and the second-largest of oil. But unlike the US, China is taking the challenge of environmental breakdown seriously. In recent years, China has spent more on greening its energy system than America and the European Union combined. China is now the world's leading investor in wind turbines and other renewable energy technologies, and produces more wind turbines and solar panels each year than any other country. Out of the 425,000 electric buses that exist worldwide today, 421,000 are in China - the U.S. accounts for a mere 300.

Under the leadership of Xi Jinping, the Communist Party of China has bold plans for the future. Since taking office in 2012, President Xi has overseen a major crackdown on corruption, and has launched a number of ambitious socio-economic reforms. Foremost among these is the 'Belt and Road Initiative' (sometimes referred to as the New Silk Road) to connect Asia with Europe and Africa in one of the grandest and most disruptive mega projects the world has ever seen.

Xi's ambitions are not limited to planet earth. Under his leadership, the regime has also placed a major emphasis on enhancing China's space capabilities as part of the nation's development strategy, referring to this as China's 'space dream'. A recent white paper setting out China's ambitions in space included plans for a lunar presence, asteroid mining and deep space exploration.

China's remarkable economic transformation has been underpinned by the country's powerful yet distinct economic model. Officially called 'socialism with Chinese characteristics', it combines strategic state ownership and planning with market-oriented incentives and a one-party political system to create a distinct economic model that remains poorly understood in the West.

Whether it is accurate to describe this system as a form of 'socialism' is another matter. Today the private sector accounts for the overwhelming majority output, employment and investment, and there is little sign of democratic workers control. As the economist Branko Milanovic puts it in his recent book, 'Capitalism, Alone':

"To qualify as capitalist, a society should be such as most of its production is conducted using privately owned means of production (capital, land), most workers are wage-labourers (not legally tied to land or working as self-employed using their own capital), and most decisions regarding production and pricing are taken in a decentralised fashion (that is, without anyone imposing them on enterprises). China scores as positively capitalistic on all three accounts."

Despite this, China's economic model is distinct from Western liberal capitalism in a number of key ways. Notably, the state holds a tight grip over the economy through a number of major institutional actors that play a crucial role in the coordination of economic activity.

One prominent example is the State-Owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC), which was formed in 2003 when a number of industry specific ministries were merged. Reporting directly to China's state council, SASAC owns and controls the firms that oversee the commanding industrial heights of the Chinese economy. The companies under its control have combined assets of $26 trillion and revenue of more than $3.6 trillion - more than the GDP of the United Kingdom - making it the largest economic entity in the world.

As Mark Wu, Assistant Professor of Law at Harvard Law School, describes:

"Imagine if one U.S. government agency controlled General Electric, General Motors, Ford, Boeing, U.S. Steel, DuPont, AT&T, Verizon, Honeywell, and United Technologies. Furthermore, imagine this agency were not simply a passive shareholder, but... could hire and fire management, deploy and transfer resources across holding companies, and generate synergies across its holdings."

Even in firms where the state is not the dominant shareholder, the Chinese party-state still has a significant amount of influence. As scholars Curtis J. Milhaupt and Wentong Zheng have highlighted, the boundary between state and private ownership of enterprise is often blurred in contemporary China. One reason for this is the role of the Communist Party in China's economic life. Each organization with more than three Communist Party members must form a Party committee within the organisation, which in many cases has a significant influence over corporate decision making. This requirement extends not only to state-owned enterprises, but also to private companies and foreign-owned firms.

Another key difference is the state's control over the finance sector. China's banking system has more than tripled in size since 2008, and is now the largest in the world. But again, China's banking sector is largely owned and controlled via a state holding company called Central Huijin Investment, which owns major stakes in the "Big Four" commercial banks and the China Development Bank. In turn, Central Huijin is a subsidiary of the China Investment Corporation, China's sovereign wealth fund. Many companies that are not state-owned receive financing on preferential terms from these public banks.

China's central bank, the People's Bank of China, also operates differently to most Western central banks. It uses an array of tools to tightly control interest rates and the amount of money in the Chinese economy, as well as the value of the Chinese renminbi relative to other currencies. Crucially, the People's Bank of China strictly controls the flows of capital in and out of the country. While capital controls have been taboo in the West for many decades, they are a crucial part of China's economic and financial architecture.

This tight control over the financial system allows the state to coordinate economic activity in a way that is not possible in most Western countries, where private finance reigns supreme. It also enables the Chinese state to insulate the domestic economy from the turbulence of global financial markets.

Perhaps the most powerful economic entity is the National Development and Reform Commission which oversees the creation of China's Five-Year Plan, and is responsible for formulating and implementing strategies for national economic and social development. This includes oversight of numerous policy areas including industrial policy, energy policy and price setting for key commodities that are not set by market forces such as electricity, oil, natural gas, and water. In addition, it is responsible for approving all large infrastructure projects and investments, regardless of whether the entity undertaking them is a state-owned enterprise, private company or foreign company.

As Milanovic notes, China's recent rulers have viewed the private sector as akin to a bird in a cage: if it is controlled too tightly, it will, like an imprisoned bird, suffocate; if it is left entirely free, it will fly away.

As China's domestic economy has grown, so has its presence abroad. In recent years Chinese entities have embarked on a vast overseas shopping spree, buying up corporations, real estate and infrastructure all over the world. In Europe alone, Chinese entities now own, or have a stake in, four airports, six maritime ports and 13 professional football teams, including Manchester City, Inter Milan and AC Milan.

Chinese investment into Africa has also soared. Since 2005, the country has pumped over $400 billion in the continent, and is now its largest trading partner, prompting analysts to talk about 'a new scramble for Africa'. Financing for major investment projects has mainly come from two state-owned banks: the Export-Import Bank of China and the China Development Bank. Using what is sometimes characterized as the "Angola Model," low-interest loans are often provided on the condition that natural resources, such as oil or mineral reserves, are used as collateral - a model that has been widely criticised for reinforcing the 'resource curse' that has trapped many African economies in poverty and dictatorship.

Through the Belt and Road Initiative, China aims to significantly expand its economic and political influence throughout Asia, Europe and Africa. To date, more than sixty countries -- accounting for two-thirds of the world's population -- have signed on to projects or indicated an interest in doing so. The investment bank Morgan Stanley has predicted that the cost to China of the initiative over the lifetime of the project could reach $1.2 to 1.3 trillion by 2027, though estimates on total investments vary.

The surveillance state

Ever since the arrival of the internet in China in 1994, authorities have taken steps to strictly monitor and control the flow of information online. In 2010, the government published the white paper 'The Internet In China' which set out its modern policy towards the internet and online activity. The paper outlined the concept of "internet sovereignty" which emphasised China's jurisdiction over web content and providers within Chinese territory. "Laws and regulations clearly prohibit the spread of information that contains content subverting state power, undermining national unity [or] infringing upon national honour and interests," it said.

Since then, the concept of 'internet sovereignty' has gained traction throughout the world and has been adopted by several states looking to control the dissemination of information online including Russia, Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Iran.

Under Xi Jinping's leadership, Chinese authorities have cracked down on subversive speech online and reinforced the so-called 'Great Firewall of China' which forms the bedrock of China's internet policy. At the same time, a rapid increase in the number of CCTV cameras means that the surveillance of online activity is now being extended into the real world. The country's 'Skynet' project, as China's surveillance network is known, plans to have over 400 million surveillance cameras installed across the country by the end of this year.

A recent study found that 8 out of the 10 cities with the most CCTV cameras per 1,000 people are in China, with Chongqing, Shenzhen and Shanghai being the most monitored cities in the world. A growing number of these cameras are powered by facial-recognition and artificial intelligence technologies, allowing authorities to track and monitor the population with a remarkable degree of sophistication.

Although China is expanding its surveillance infrastructure throughout the country, it is in the western province of Xinjiang where it is most prevalent. Human rights groups report that the Chinese government is detaining and surveilling millions of people from the minority Muslim Uighur population on an unprecedented scale. As well as mass surveillance using facial recognition technologies, police have also conducted large scale DNA swabs, iris scans and blood tests in order to build a region-wide biometric database.

"The Xinjiang police used a facial-recognition app on me", Yuan Yang, a correspondent at the Financial Times, reported from the region last year. "When I checked into a hotel, a police officer came to the lobby to register me with her smartphone. She opened up an app and logged into it by scanning her own face. Then she took a photo of my passport profile page from within the app. Finally, the police officer asked to scan my face. Immediately, three women's faces came up on her screen. The top one was an old visa-application photo of mine that I could barely remember having been taken. Clicking through to it showed her my full passport information."

The surveillance state is also integral to the government's plans to roll out a 'Social Credit' system. First described in an official document in 2014, the scheme has already been piloted in various forms in several cities and is expected to become fully operational this year. The system will use big data to track the trustworthiness of everyday citizens, corporations, and government officials and allocate them a score based on past behaviour. Socially desirable behaviour will be rewarded with good credit, while undesirable behaviour will result in sanctions, such as being banned from purchasing plane or train tickets.

On current trends, China is on track to become a surveillance superpower. But it is not the only technology that Beijing has big plans for.

A new technological cold war

For decades many Western economists assumed that China would follow the path of other planned economies: a rapid state-led mobilisation of resources would generate an initial period of strong growth, but this would not last. The theory was that state-led systems were effective at rapidly mobilising capital and labour resources, but they were less effective at increasing productivity - meaning that growth would stall once all the available inputs were being deployed. Growth would be based on "perspiration" not "inspiration", as Paul Krugman famously remarked in 1994, meaning that it could not be sustained.

China's achievements so far have already proven these critics wrong. But it is Beijing's plans for the future that have set alarm bells ringing in Washington. Strategists fear that China's ambitious suite of industrial policies could lead to the US losing technological supremacy in key strategic sectors - along with the economic, military and geopolitical power that comes with it.

The chief offender is the 'Made in China 2025' initiative. Launched in 2015, Made in China 2025 is a ten year plan for China to achieve self-sufficiency in strategic technologies such as advanced information technology, robotics, aerospace, green vehicles and biotechnology. The strategy is reported to be at the very top of President Xi Jinping's economic priorities.

As soon as it was announced, Made in China 2025 alarmed many analysts in Washington. In 2018, the US think tank Council on Foreign Relations described Made in China 2025 as a "real existential threat to U.S. technological leadership." The US Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer has described the initiative as "a very, very serious challenge".

When the Trump administration first imposed higher tariffs on Chinese goods in June 2018, the tariff list mainly focuses on products included in the Made in China 2025 plan, such as IT and robotics related products.

The president's demands in early trade negotiations focused on requiring China to cut state support for high tech industries, stop "forcing" foreign companies to share technology with Chinese enterprises, remove ownership restrictions on incoming investments and - crucially - scrap the Made in China 2025 policy.

In response, the Chinese government started to downplay Made in China 2025, and avoided discussing the initiative publicly. Although there were reports that Beijing abandoned the initiative in late 2018, in practice the change in direction was more cosmetic than real.

In January this year, the US and China signed a long-awaited trade deal. While the deal may have achieved enough to make Donald Trump look tough during his re-election campaign, it has done little to assuage the underlying tensions. The deal includes no provisions on the Made in China 2025 initiative or subsidies for state-owned enterprises. Instead, China has committed to vague pledges not to "support or direct" acquisitions and investment by Chinese companies of foreign technology in "industries targeted by its industrial plans that create distortion." The White House maintains that it will tackle other outstanding issues in a second "phase two" deal in the near future.

From the very beginning, the trade war has been less about trade, and more about constraining Chinese development and preventing China's rise as a rival technological power.

Caught in the crossfire have been companies such as Huawei. Although not a state-owned enterprise, Huawei has received significant support from the Chinese state, including a $30 billion line of credit from the China Development Bank. Thanks in part to this support, Huawei has emerged as the global leader in the development of 5G networks - a technology that is widely expected to be the backbone of the modern digital economy. As a Foreign Policy recently reported: "5G will be the central nervous system of the 21st-century economy -- and if Huawei continues its rise, then Beijing, not Washington, could be best placed to dominate it."

In response to fears over Huawei's dominance, the Trump administration banned the company from acquiring US parts and software and selling its products in the US, and has applied significant diplomatic pressure on allies such as the UK to avoid doing business with Huawei.

The US government's motivation is clear: to crush one of the first Chinese tech companies to become globally competitive, and prevent it from gaining a dominant position in a key technology of the future. Huawei may be the first major company to be in the firing line, but it is unlikely to be the last.

It's not just Uncle Sam that is tightening the screw on China - the tech titans of Silicon Valley have also become increasingly concerned about China's rise.

In a speech in December last year, Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos warned American military leaders that the US risks losing its superiority in key technologies to China - an advantage which has long been the bedrock of the country's military might.

Speaking at the Reagan National Defense Forum, the world's wealthiest individual said: "Do you really want to plan for a future where you have to fight with someone who is as good as you are? This is not a sporting competition. You don't want to fight fair."

To a delighted audience, Bezos said that America's data giants had a duty to make their technology available to the Pentagon to ensure that "freedom and democracy" are preserved. While the kingpins of Silicon Valley once viewed China as the next big market to be exploited, they now increasingly view it as a systemic threat to be contained.

You don't want to fight fair.-Jeff Bezos, CEO and president of Amazon

The coronavirus pandemic has only heightened these tensions further. It was recently reported that the Trump administration is considering tightening rules to prevent Chinese companies from purchasing goods containing advanced US technology such as optical materials, radar equipment and semiconductors. In practice however, such measures are only likely to stiffen Beijing's resolve to become self-sufficient in the development of key technologies.

These rising tensions point to the emergence of a new technological cold war. In the not-too-distant future, we may find ourselves in a world where countries may be able to use US technology or Chinese technology - but not both.

The end of the American century?

China's rise has led some to speculate that we are witnessing the 'end of the American century'. However, until recently there have always been persuasive reasons to believe that such premonitions were premature.

In April last year, the historian Adam Tooze noted that: "As of today, it is a gross exaggeration to talk of an end to the American world order. The two pillars of its global power - military and financial - are still firmly in place. What has ended is any claim on the part of American democracy to provide a political model."

As Tooze and others have documented, the global financial crisis only served to reinforce the global economy's reliance on the dollar. As global banks became increasingly desperate for dollar liquidity, the Federal Reserve transformed itself into a global lender of last resort by establishing dollar swap lines with other central banks. These swap lines provided dollars to foreign central banks in exchange for the local currency, with a promise to swap back once the crisis period had subsided.

Partly as a result of this action, today the global financial system is more dependent on the dollar than ever before, and the dollar remains the world's pre-eminent global reserve currency. With this power comes great privilege: the US can punish any company or country it doesn't like by issuing sanctions which exclude them from the dollar system, and by extension the world economy. At the same time, the US still spends more on defence than the next ten largest countries combined, and the multilateral order is still shaped around American interests.

But some believe that the coronavirus pandemic could represent a pivotal turning point in the balance of power between West and East. Carl Bildt, the former Swedish Prime Minister, recently described the pandemic as "the first great crisis of the post-American world", pointing to the absence of US leadership on the world stage. The evident decay in the quality of US governance and Washington's eschewing of multilateral cooperation is certainly not going unnoticed among world leaders. As the Financial Times's Martin Wolf recently commented: "A government at war with science and its own machinery is now very visible to all."

This is the first great crisis of the post-American world.-Carl Bildt, former Swedish Prime Minister

But there is one place where US leadership is quietly working on overdrive: the Federal Reserve. While investors have sought refuge in Chinese government bonds to a greater extent than ever before, they have also scrambled to buy dollars and US Treasury bonds - the world's traditional 'safe haven' assets.

Since January, around $96 billion has flowed out of emerging markets, according to data from the Institute for International Finance. This is more than triple the $26 billion outflow during the financial crisis of a decade ago. This "sudden stop" in dollar funding has caused currencies to plummet and borrowing costs to rise in many developing countries. Combined with a collapse in commodity prices and fragile healthcare systems, this has left many countries dangerously exposed to the pandemic.

This rush to safety has also created a global shortage of dollars which, if allowed to continue, could leave many countries unable to obtain the currency they need to meet their dollar denominated liabilities. As in 2008, the Fed has responded aggressively by reopening swap lines, including to selected emerging market economies such as Mexico and Brazil. It has also gone further by introducing a repurchase agreement facility for foreign central banks. In doing so, it has once again demonstrated its unparalleled power and reach - and exposed the global financial system's deep reliance on the dollar.

But there is one major central bank that does not have an arrangement in place to access dollars at the Federal Reserve: the People's Bank of China. Given the frosty relations between the two powers, this is perhaps unsurprising. But this blockage in the global financial plumbing could have significant consequences.

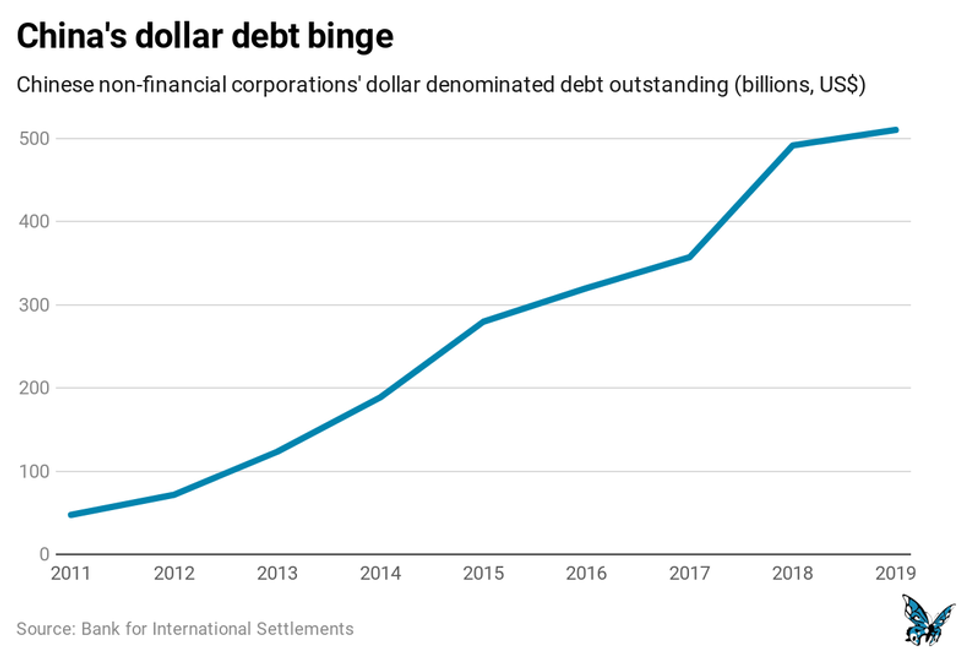

In recent years Chinese businesses have amassed large debts denominated in dollars. Crucially, many of the sectors hardest hit by the coronavirus outbreak, such as airlines and real-estate development, are also among the most likely to have high dollar-denominated debt burdens. If these companies find themselves in difficulty, it could spark a scramble for dollar funding in China. Without access to a dollar swap line, the People's Bank of China may be forced to play its trump card.

The prospect of China suddenly deciding to sell its vast $1 trillion holding of US Treasury bonds has haunted markets for over a decade. Up until now, it has not been in China's interests to try and destabilise the dollar based global financial system. But some believe that the rising tensions from the coronavirus pandemic, combined with the erosion of US soft power, could mean that things are about to change.