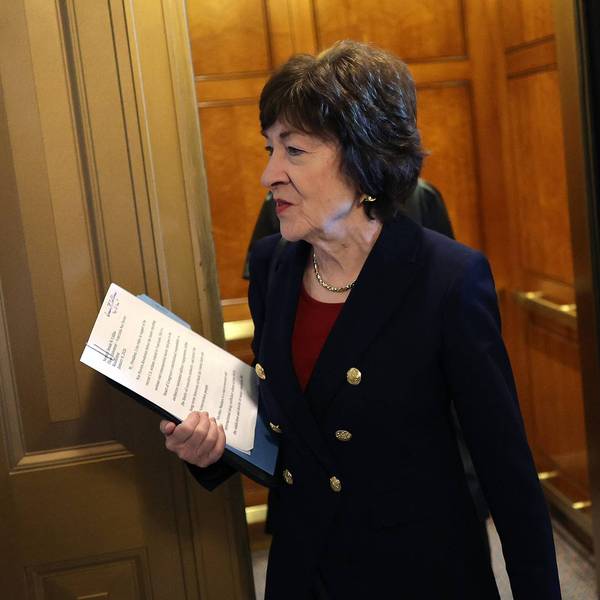

On the first leg of a trip last week to work at the Maxwell School for Citizenship at the University of Syracuse, I flew from Bangor, Maine, to Washington, D.C. Sitting across from me in aisle two was one of Maine's senators, Susan Collins, a woman of enormous power, seniority and prestige in the Republican Party and our government. How often, I thought, does one get the serendipitous opportunity to talk with a senator? But another passenger sat between us, and I could not engage her.

This was a commuter flight in a small jet, the kind that does not connect to a walkway into the terminal, but has the passengers disembark and stand outside the plane as they wait for their luggage to be brought forward. Senator Collins happened to stand, waiting for her bag, next to me. I leaned over and introduced myself. I had hoped to take this moment to ask her some questions about the maintenance of democracy. If you are inclined to say my intended conversation was a bit heavy for a windy and noisy tarmac, you would be correct.

Senator Collins began to offer me the public smile commonly bestowed on friendly constituents, but paused. My name must have set off a little alarm in her head. She gave me a brief look--I'm not sure I could read it--anger? dismay?--and said in an even voice, "We are not friends," turned her back on me and walked away.

Her response did not come from nowhere. Indeed, we are not friends. I have never called her Susie, nor has she called me Rob. In fact, I have tried to be a thorn in her side, having been arrested twice in her office in peaceful, civil disobedient protests against her support of the Iraq War. And on two other occasions I politely interrupted public speeches of hers when she was defending and supporting the Bush war policies. I have gone to jail, paid fines, and done community service in vain attempts to influence her positions or at least have others recognize them for what they were. But, it's important to note, each of the protests came after appealing to her office to allow me and others to meet her face to face to discuss these issues. We were always refused.

Most of the time, those of us who protest public policies feel that people in power pay attention to neither the protests nor the people who protest. When Senator Collins walked away from me on the tarmac it seemed nearly positive; at least she knew who I was. At the same time, I knew enough not to take "We are not friends" personally. She was addressing all of us who think it is our duty as citizens to oppose her policies. And I might have presumed that her duty as a public servant was to at least listen to views that make her uncomfortable.

You can imagine my frustration. So close to a Senator I've wanted to engage and then given her back. She was probably afraid I might make a scene, begin calling her a baby killer or pour flour on her head. But such is the strange dance of power and protest in this country. The power uses all the means of security and privilege to avoid direct conversation with people who disagree. The opposition resorts to civil disobedience and interruption because our "democracy" has not allowed any other form of communication. And then, when coincidence places them in the same place at the same time, the distrust is too deep to span. For Senator Collins to say, "We are not friends," admits a sad defeat for political dialogue.

I don't want to be the senator's personal friend, but I really would like to discuss with her the crises besetting this country and the world and how to remedy them.

What is the price of this incivility, this distrust? I don't want to be the senator's personal friend, but I really would like to discuss with her the crises besetting this country and the world and how to remedy them. We don't have to agree. But I do believe that she should invite those of us who have different views to be part of the conversation. How can we be friends of the world together, joined by shared concerns and able to discuss climate change, environmental degradation, war, the incompatibility of democracy with the influence of enormous wealth, unsustainable economics, poor education, energy depletion, industrial farming, debt, unemployment, and a host of other issues? How do we get beyond political expediency, campaign contributions and corporate profits to discuss these things?

Senator Collins, along with Maine's other Senator, Olympia Snowe, has decried the intractable partisanship of our current government--politicians entrusted with the enormous task of solving critical problems as millions (no, billions!) of people and other species are affected by their obdurate inaction. Perhaps my brief interaction with her was a perfect example of the absurdity of this inability to talk. Jack Kennedy said, "Those who make peaceful revolution impossible will make violent revolution inevitable." So we might say those who make formal friendship based on a common concern for our destiny impossible make partisanship inevitable. They make the possible impossible.

I'm sure Senator Collins considers how history might write her story. She is already famous for all the obvious, prestigious reasons. But there is only one sure way to earn an exemplary niche. And that is moral courage -- the courage to listen to the other side, to insist on what is right, not expedient, the courage to inhabit what Terry Tempest Williams calls "the open space of democracy." Senator, let's start a conversation. I promise not to pour flour on your head. And you could promise not to pour cold water on me.