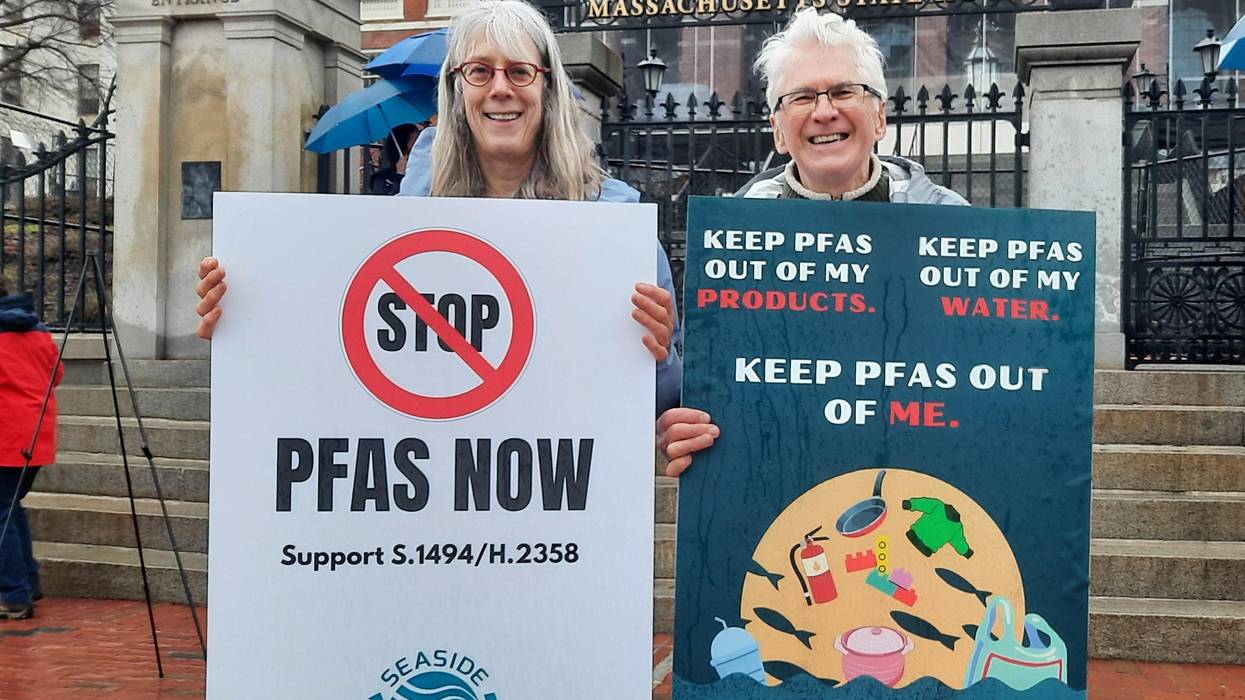

Industry Braces for PFAS Lawsuits That Could 'Dwarf' Those of Asbestos, Tobacco

The warning of litigation to plastics makers comes as EPA is accused of failing to adequately test for "forever chemicals" in pesticides.

A newly reported warning to the plastics industry and a complaint filed by an environmental nonprofit this week highlighted how companies and the U.S. government have endangered the public with "forever chemical" contamination.

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are commonly called forever chemicals because they remain in the human body and environment for long periods. They have been used in products such as firefighting foam, food packaging, stain-resistant fabrics, and pesticides, and linked to various health problems including cancers and issues with reproduction.

The New York Times reported Tuesday that attorney Brian Gross recently told plastics executives that looming corporate liability litigation related to PFAS—some of which has already begun—could "dwarf anything related to asbestos," and lead to "astronomical" costs.

As the newspaper detailed:

"Do what you can, while you can, before you get sued," Mr. Gross said at the February session, according to a recording of the event made by a participant and examined by The New York Times. "Review any marketing materials or other communications that you've had with your customers, with your suppliers, see whether there's anything in those documents that's problematic to your defense," he said. "Weed out people and find the right witness to represent your company."

A spokesman for Mr. Gross' employer, MG+M The Law Firm, which defends companies in high-stakes litigation, didn't respond to questions about Mr. Gross' remarks and said he was unavailable to discuss them.

While Gross declined to comment, Emily M. Lamond, who focuses on environmental law at the firm Cole Schotz, told the Times that "to say that the floodgates are opening is an understatement."

"Take tobacco, asbestos, MTBE, combine them, and I think we're still going to see more PFAS-related litigation," Lamond said, referring to methyl tert-butyl ether. The newspaper noted that "together, the trio led to claims totaling hundreds of billions of dollars."

Back in 2005, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency announced that DuPont would "pay $10.25 million—the largest civil administrative penalty EPA has ever obtained under any federal environmental statute—to settle violations alleged by EPA" related to PFAS and commit to $6.25 million for supplemental environmental projects.

The EPA has also taken more recent actions under President Joe Biden's "PFAS Strategic Roadmap," including designating perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) as hazardous substances under the Superfund law and setting the country's first-ever drinking water standards for those and other forever chemicals.

The Biden administration's steps, as the Times pointed out, are expected to fuel future litigation. Green groups have called the EPA's recent moves progress but not nearly enough—and as Capital B reported earlier this month, there are concerns that PFAS cleanup could disproportionately burden communities home to the working class and people of color.

On top of calls to go further with regulation and cleanup efforts, the EPA is facing pressure to retract what Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility (PEER) called "false statements" in a 2023 agency research memo and press release. The group filed a formal complaint with the EPA on Tuesday demanding a correction.

"This memo is some of the worst science I have seen come out of the agency," said PEER science policy director Kyla Bennett, a scientist and former EPA attorney, in a statement. "The fact that EPA claimed it could not find any PFAS in samples deliberately spiked is incredibly troubling."

"Scientists around the world are finding PFAS in pesticides from active and inert ingredients, contamination from fluorinated containers, and unknown sources," she continued. "EPA's claim that it 'did not find any PFAS' in these pesticides is not only untrue but lulls the public into a false sense of security that these products are PFAS-free."

Asked about PEER's submission by journalist Carey Gillam, the agency—which has 90 days to respond—said that "because these issues relate to a pending formal complaint process, EPA has no further information to provide."

Gillam reported that "joining in the allegations is environmental toxicologist Steven Lasee, who authored the 2022 study that the EPA challenged. Lasee is a consultant for state and federal government agencies on PFAS contamination projects and participated as a research fellow for the EPA's Office of Research and Development from February 2021 to February 2023."

As Gillam detailed at New Lede and The Guardian:

Amid the uproar over his paper and the subsequent EPA testing, Lasee sought to reproduce his initial results but was unable to do so. That created enough doubt about his own methodology that he sought to retract his paper.

Now, after seeing the EPA's internal testing data showing the agency did find PFOS and other types of PFAS in pesticides but failed to disclose those results, he has a new level of doubt—over the credibility of the agency.

"When you cherrypick data, you can make it say whatever you want it to say," Lasee said.

PEER's Bennett similarly said that "you don't get to just ignore the stuff that doesn't support your hypothesis. That is not science. That is corruption. I can only think that they were getting pressure from pesticide companies."