SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

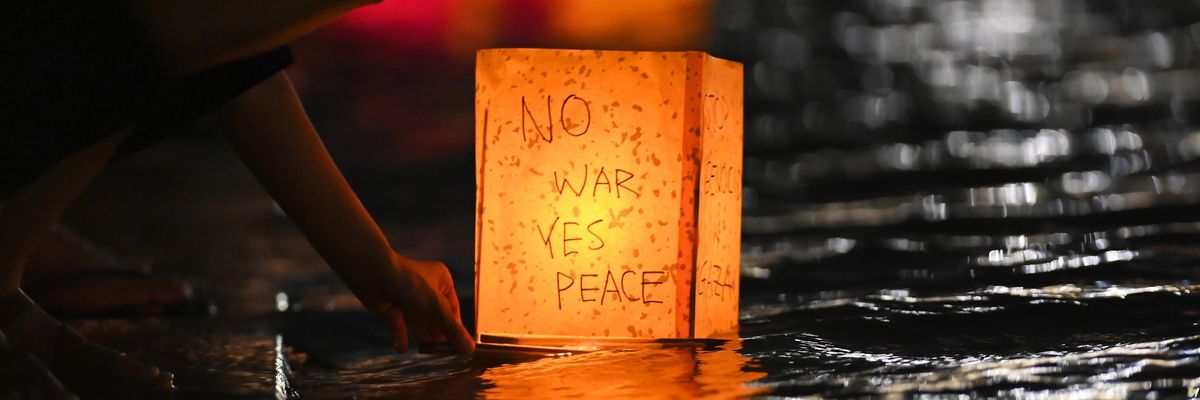

People attend the Peace Message Lantern Floating Ceremony in front of the Atomic Dome Bomb at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park to pay tribute to the atomic bomb victims in Hiroshima, Japan, on August 6, 2025.

They have been telling their stories for nearly 80 years. It’s about time more of us listen.

CONTENT WARNING: This article contains descriptions of nuclear weapons effects, including disturbing accounts of the victims.

On August 6, 1945, the United States dropped the first atomic bomb ever used in warfare on the city of Hiroshima, Japan. Three days later, on August 9, the second was dropped on Nagasaki. Both cities were totally destroyed by the bombs, a new type of weapon developed by the United States, infamously through the Manhattan Project. In Hiroshima, over 140,000 were killed. In Nagasaki, over 70,000. In the blink of an eye, humanity witnessed two of the darkest days in history.

This year marks the 80th commemoration of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Each year, scores of Japanese peace organizations, and those from other nations, hold events in the two cities to remember the tragedies and renew passions for continuing the fight for peace.

This year, I had the privilege of being invited to attend one such event: the World Conference Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs, organized by Gensuikyo. It has been a tremendous honor to join as part of a delegation from the United States and as a representative of the Campaign for Peace, Disarmament, and Common Security, an organization whose board I sit on.

What I have experienced has moved me powerfully. I learned from testimony from nuclear bomb survivors (Hibakusha), technical descriptions of the events of those days, diplomatic arguments from around the world, and demonstrations of peace movements from Japan and beyond. In the aftermath of such powerful testimony, the natural conclusion is inescapable: Nuclear weapons should be made illegal, never used again, and dismantled. The wealth of resources going toward their production should instead be dedicated to programs that actually create security like education, diplomacy, material security, and cooperative institutions.

I’d like to report back what I experienced and learned for the benefit of those unfamiliar with the details of nuclear weapons control—especially those in the United States. As someone who grew up through U.S. public schools and engages with students in higher education, I can say that we are woefully ignorant of the truth. Let this correct the record and help open more eyes to the truth.

I want to share both the technical details of what happened during nuclear bomb detonation as well as testimony from those who survived the blasts, the Hibakusha. Both are difficult to read. I urge readers to open their minds and hearts and imagine to their greatest ability what those who experienced the bombings felt like as horror unfolded before their very eyes.

At the World Conference, Professor Oya Masato of the Nagasaki Institute of Applied Science shared a scientific account of the bombing of Nagasaki. This second bomb exploded at 11:02 am on August 9, 1945, 503 meters above the town of Matsuyama, about three kilometers north of Nagasaki city center. Instantly, the bomb turned into a fireball of tens of millions of degrees. The surface of the fireball cooled to approximately 7,000°C in 0.1 seconds. The ground temperature at the hypocenter (point of detonation) rose as high as 3,000-4,000°C, and humans in the area were instantly carbonized. The bomb generated a shock wave and blast which traveled at 440 meters per second at the hypocenter and 60 meters per second two kilometers away from the hypocenter. Those shock waves destroyed most of the city, an area of 405 square kilometers, within 10 seconds. Fires emerged and burned an area of 6.7 square kilometers. Thousands were instantly killed, and by the end of 1945, the death toll rose to 74,000.

This scientific description begins to describe the horrors of the bomb. But it can be hard to imagine. What stands out is the sheer power and devastation: a whole city leveled and engulfed in flames within seconds. Devastation on a scale never before seen. Callous destruction, indiscriminate murder.

What truly rends the heart is the testimony of Hibakusha, those who survived the bomb and tell their stories. The Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum depicts many such stories. It’s nearly unbearable to take in and try to imagine even a sliver of what these horrors would feel like. The stories make clear that the atomic bombs created a literal hell on Earth.

A device that can cause this amount of suffering has no place in human society.

One story, shared by a Hibakusha of Hiroshima, Park Jung-soon, 11 years old at the time, describes her experience. On the morning of the bombing, she and her six family members living together were surprised by a flash like lightning and thunder. The sky lit up. Suddenly, a blast and tremendous sound shook the whole house, lifting the entire structure upward. The house fell back down, collapsed, and crushed the family beneath it. It all happened in seconds. They could not move their bodies and thought they would die.

Imagine the sheer terror of suddenly being launched into the air only to plummet down and be crushed by your home. Imagine your home, something that we hold deep attachment to and a place of safety, comfort, and love, collapsing down on you and your whole family. In moments your safe haven becomes the source of incredible pain. Imagine those you love looking at you with the fear of death in their eyes for a split second before having your gaze ripped away by the force of crushing weight.

Jung-soon opened her eyes and found herself trapped under a thick beam. Her mother desperately pulled her out and helped her crawl out of the collapsed walls. Her head was bleeding heavily, but she rose to her feet and looked around: The house next door had fallen down as well, people were running away, crying, shouting. The village as she knew it was falling apart.

While the family fled, they saw people dead on the ground, or alive but in agony crying or shouting. People were pulling carts carrying wounded or dead neighbors. People were covered in burns and suffering in pain. She describes it as like the hell of a cartoon but in reality.

At the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, there were many such stories and testimonies, as well as photographs and artwork created by Hibakusha attempting to visually depict what they experienced. Details like those in Jung-soon’s story were common. People burned beyond recognition. Structures flattened. The dead littering the city. People walking around with flesh peeling from their bodies, literally melting off, begging and screaming for water. It was, indeed, hell on Earth.

It may be difficult, but I implore you to try to deeply imagine what these words convey. In a world where many of us are constantly exposed to language of indiscriminate violence through news media, it may be easy to simply read this and register it as fact. But try to register it as feeling. What would it feel like to feel your own broken body throb with pain while simultaneously witnessing mass death all around you? Can you imagine a human being burnt beyond recognition? Someone with their flesh melting off? The sounds of screams, crying, wailing, and pure fear were profoundly traumatizing.

The effects of nuclear weapons, the scenes described by the Hibakusha, are things that should never be visited upon this Earth. A device that can cause this amount of suffering has no place in human society.

This does not even describe the effects of the bombing that persisted long after the initial devastation. Hibakusha faced severe effects from radiation poisoning and the physical damage—burns, breakages, disfigurations—they sustained. They were also subject to discrimination for decades, as people feared contamination if they came in contact with Hibakusha. Many kept their stories secret.

These are tragic tales that the Japanese peace movement describes and uplifts for all to learn from. They have been telling their stories for nearly 80 years. It’s about time more of us listen.

In the United States, there is a profound culture of ignorance surrounding nuclear weapons. I experienced this firsthand growing up in U.S. public schools and then in collegiate engineering studies.

When I was in high school, I elected to take the upper-level U.S. history class—one which gives college credit if you do well enough. The course is infamous in American high schools: AP U.S. History, or APUSH for short. Our teacher taught out of a book used in many classrooms across the country, titled The American Pageant: A History of the Republic by Kennedy, Cohen, and Bailey. This book, like many others used in the U.S., describes the atomic bombing as the key to ending the second World War, a tough but necessary decision by President Harry Truman. The argument goes that dropping the bombs eliminated the need for a U.S. ground invasion, which would have cost half a million lives (which Howard Zinn notes in A People’s History of the United States seemed to have “been pulled out of the air to justify the bombings”). It becomes a trolly problem of sorts: Would you end 200,000 lives to save half a million?

That’s as far as we typically get in U.S. depictions of the bombings. We are stuck thinking at a high school level about nuclear weapons—in a country whose high schools are not known for their rigor or nuanced teaching of U.S. history. Now, when I teach at universities and talk with students in engineering, their understanding of the bombings is the same: an unfortunate necessity or political blunder. Even the faculty teaching the course, presumably sharp thinkers with PhDs, repeat the same lines.

Students should not be indoctrinated into a version of the story favorable to the U.S. perspective.

In popular media, the story is no different. 2023’s blockbuster Oppenheimer—which broke box office expectations and was given seven awards at the Oscars—was a shallow depiction of the events. As it told a dramatized version of Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer’s work on the Manhattan Project, it attempted to depict his inner turmoil as he grappled with visions of what must have become of victims. However, the screen time dedicated to his haunting visions does not exceed five minutes in a three-hour film.

Accurate depictions of the horrors of nuclear bombings are nowhere to be found in dominant U.S. education and media. Textbooks do not describe the detailed suffering of victims, the social discrimination they experienced afterward, or the stories of their deeply difficult lives. Films choose not to center the victims of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but rather the perpetrators. It is tragic and laughable to consider the fact that a film like Oppenheimer is praised for its critique of nuclear weapons while it entirely centers the life of the man who was instrumental in their creation rather than the lives of his victims.

Peace organizations across the U.S. are pushing against these narratives, trying to spread the truth, and fighting for nonproliferation. But without countering the widespread ignorance of our own population, we will not get far. In a world increasingly plagued by misinformation and falsehood, we have our work cut out when it comes to effectively spreading the truth about nuclear weapons. We need to dispel the veil of ignorance covering our communities if we are to build a large enough movement to push the U.S. to disarm, re-engage in treaties, and work toward peace under cooperation rather than precarious stability based on fear and threats.

One of the first steps can be to simply tell the truth. Stories matter, and how we tell the history of our own nation matters. Students should not be indoctrinated into a version of the story favorable to the U.S. perspective. Media should accurately describe the horrors. The stories of the Hibakusha should be known by everyone.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

CONTENT WARNING: This article contains descriptions of nuclear weapons effects, including disturbing accounts of the victims.

On August 6, 1945, the United States dropped the first atomic bomb ever used in warfare on the city of Hiroshima, Japan. Three days later, on August 9, the second was dropped on Nagasaki. Both cities were totally destroyed by the bombs, a new type of weapon developed by the United States, infamously through the Manhattan Project. In Hiroshima, over 140,000 were killed. In Nagasaki, over 70,000. In the blink of an eye, humanity witnessed two of the darkest days in history.

This year marks the 80th commemoration of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Each year, scores of Japanese peace organizations, and those from other nations, hold events in the two cities to remember the tragedies and renew passions for continuing the fight for peace.

This year, I had the privilege of being invited to attend one such event: the World Conference Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs, organized by Gensuikyo. It has been a tremendous honor to join as part of a delegation from the United States and as a representative of the Campaign for Peace, Disarmament, and Common Security, an organization whose board I sit on.

What I have experienced has moved me powerfully. I learned from testimony from nuclear bomb survivors (Hibakusha), technical descriptions of the events of those days, diplomatic arguments from around the world, and demonstrations of peace movements from Japan and beyond. In the aftermath of such powerful testimony, the natural conclusion is inescapable: Nuclear weapons should be made illegal, never used again, and dismantled. The wealth of resources going toward their production should instead be dedicated to programs that actually create security like education, diplomacy, material security, and cooperative institutions.

I’d like to report back what I experienced and learned for the benefit of those unfamiliar with the details of nuclear weapons control—especially those in the United States. As someone who grew up through U.S. public schools and engages with students in higher education, I can say that we are woefully ignorant of the truth. Let this correct the record and help open more eyes to the truth.

I want to share both the technical details of what happened during nuclear bomb detonation as well as testimony from those who survived the blasts, the Hibakusha. Both are difficult to read. I urge readers to open their minds and hearts and imagine to their greatest ability what those who experienced the bombings felt like as horror unfolded before their very eyes.

At the World Conference, Professor Oya Masato of the Nagasaki Institute of Applied Science shared a scientific account of the bombing of Nagasaki. This second bomb exploded at 11:02 am on August 9, 1945, 503 meters above the town of Matsuyama, about three kilometers north of Nagasaki city center. Instantly, the bomb turned into a fireball of tens of millions of degrees. The surface of the fireball cooled to approximately 7,000°C in 0.1 seconds. The ground temperature at the hypocenter (point of detonation) rose as high as 3,000-4,000°C, and humans in the area were instantly carbonized. The bomb generated a shock wave and blast which traveled at 440 meters per second at the hypocenter and 60 meters per second two kilometers away from the hypocenter. Those shock waves destroyed most of the city, an area of 405 square kilometers, within 10 seconds. Fires emerged and burned an area of 6.7 square kilometers. Thousands were instantly killed, and by the end of 1945, the death toll rose to 74,000.

This scientific description begins to describe the horrors of the bomb. But it can be hard to imagine. What stands out is the sheer power and devastation: a whole city leveled and engulfed in flames within seconds. Devastation on a scale never before seen. Callous destruction, indiscriminate murder.

What truly rends the heart is the testimony of Hibakusha, those who survived the bomb and tell their stories. The Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum depicts many such stories. It’s nearly unbearable to take in and try to imagine even a sliver of what these horrors would feel like. The stories make clear that the atomic bombs created a literal hell on Earth.

A device that can cause this amount of suffering has no place in human society.

One story, shared by a Hibakusha of Hiroshima, Park Jung-soon, 11 years old at the time, describes her experience. On the morning of the bombing, she and her six family members living together were surprised by a flash like lightning and thunder. The sky lit up. Suddenly, a blast and tremendous sound shook the whole house, lifting the entire structure upward. The house fell back down, collapsed, and crushed the family beneath it. It all happened in seconds. They could not move their bodies and thought they would die.

Imagine the sheer terror of suddenly being launched into the air only to plummet down and be crushed by your home. Imagine your home, something that we hold deep attachment to and a place of safety, comfort, and love, collapsing down on you and your whole family. In moments your safe haven becomes the source of incredible pain. Imagine those you love looking at you with the fear of death in their eyes for a split second before having your gaze ripped away by the force of crushing weight.

Jung-soon opened her eyes and found herself trapped under a thick beam. Her mother desperately pulled her out and helped her crawl out of the collapsed walls. Her head was bleeding heavily, but she rose to her feet and looked around: The house next door had fallen down as well, people were running away, crying, shouting. The village as she knew it was falling apart.

While the family fled, they saw people dead on the ground, or alive but in agony crying or shouting. People were pulling carts carrying wounded or dead neighbors. People were covered in burns and suffering in pain. She describes it as like the hell of a cartoon but in reality.

At the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, there were many such stories and testimonies, as well as photographs and artwork created by Hibakusha attempting to visually depict what they experienced. Details like those in Jung-soon’s story were common. People burned beyond recognition. Structures flattened. The dead littering the city. People walking around with flesh peeling from their bodies, literally melting off, begging and screaming for water. It was, indeed, hell on Earth.

It may be difficult, but I implore you to try to deeply imagine what these words convey. In a world where many of us are constantly exposed to language of indiscriminate violence through news media, it may be easy to simply read this and register it as fact. But try to register it as feeling. What would it feel like to feel your own broken body throb with pain while simultaneously witnessing mass death all around you? Can you imagine a human being burnt beyond recognition? Someone with their flesh melting off? The sounds of screams, crying, wailing, and pure fear were profoundly traumatizing.

The effects of nuclear weapons, the scenes described by the Hibakusha, are things that should never be visited upon this Earth. A device that can cause this amount of suffering has no place in human society.

This does not even describe the effects of the bombing that persisted long after the initial devastation. Hibakusha faced severe effects from radiation poisoning and the physical damage—burns, breakages, disfigurations—they sustained. They were also subject to discrimination for decades, as people feared contamination if they came in contact with Hibakusha. Many kept their stories secret.

These are tragic tales that the Japanese peace movement describes and uplifts for all to learn from. They have been telling their stories for nearly 80 years. It’s about time more of us listen.

In the United States, there is a profound culture of ignorance surrounding nuclear weapons. I experienced this firsthand growing up in U.S. public schools and then in collegiate engineering studies.

When I was in high school, I elected to take the upper-level U.S. history class—one which gives college credit if you do well enough. The course is infamous in American high schools: AP U.S. History, or APUSH for short. Our teacher taught out of a book used in many classrooms across the country, titled The American Pageant: A History of the Republic by Kennedy, Cohen, and Bailey. This book, like many others used in the U.S., describes the atomic bombing as the key to ending the second World War, a tough but necessary decision by President Harry Truman. The argument goes that dropping the bombs eliminated the need for a U.S. ground invasion, which would have cost half a million lives (which Howard Zinn notes in A People’s History of the United States seemed to have “been pulled out of the air to justify the bombings”). It becomes a trolly problem of sorts: Would you end 200,000 lives to save half a million?

That’s as far as we typically get in U.S. depictions of the bombings. We are stuck thinking at a high school level about nuclear weapons—in a country whose high schools are not known for their rigor or nuanced teaching of U.S. history. Now, when I teach at universities and talk with students in engineering, their understanding of the bombings is the same: an unfortunate necessity or political blunder. Even the faculty teaching the course, presumably sharp thinkers with PhDs, repeat the same lines.

Students should not be indoctrinated into a version of the story favorable to the U.S. perspective.

In popular media, the story is no different. 2023’s blockbuster Oppenheimer—which broke box office expectations and was given seven awards at the Oscars—was a shallow depiction of the events. As it told a dramatized version of Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer’s work on the Manhattan Project, it attempted to depict his inner turmoil as he grappled with visions of what must have become of victims. However, the screen time dedicated to his haunting visions does not exceed five minutes in a three-hour film.

Accurate depictions of the horrors of nuclear bombings are nowhere to be found in dominant U.S. education and media. Textbooks do not describe the detailed suffering of victims, the social discrimination they experienced afterward, or the stories of their deeply difficult lives. Films choose not to center the victims of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but rather the perpetrators. It is tragic and laughable to consider the fact that a film like Oppenheimer is praised for its critique of nuclear weapons while it entirely centers the life of the man who was instrumental in their creation rather than the lives of his victims.

Peace organizations across the U.S. are pushing against these narratives, trying to spread the truth, and fighting for nonproliferation. But without countering the widespread ignorance of our own population, we will not get far. In a world increasingly plagued by misinformation and falsehood, we have our work cut out when it comes to effectively spreading the truth about nuclear weapons. We need to dispel the veil of ignorance covering our communities if we are to build a large enough movement to push the U.S. to disarm, re-engage in treaties, and work toward peace under cooperation rather than precarious stability based on fear and threats.

One of the first steps can be to simply tell the truth. Stories matter, and how we tell the history of our own nation matters. Students should not be indoctrinated into a version of the story favorable to the U.S. perspective. Media should accurately describe the horrors. The stories of the Hibakusha should be known by everyone.

CONTENT WARNING: This article contains descriptions of nuclear weapons effects, including disturbing accounts of the victims.

On August 6, 1945, the United States dropped the first atomic bomb ever used in warfare on the city of Hiroshima, Japan. Three days later, on August 9, the second was dropped on Nagasaki. Both cities were totally destroyed by the bombs, a new type of weapon developed by the United States, infamously through the Manhattan Project. In Hiroshima, over 140,000 were killed. In Nagasaki, over 70,000. In the blink of an eye, humanity witnessed two of the darkest days in history.

This year marks the 80th commemoration of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Each year, scores of Japanese peace organizations, and those from other nations, hold events in the two cities to remember the tragedies and renew passions for continuing the fight for peace.

This year, I had the privilege of being invited to attend one such event: the World Conference Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs, organized by Gensuikyo. It has been a tremendous honor to join as part of a delegation from the United States and as a representative of the Campaign for Peace, Disarmament, and Common Security, an organization whose board I sit on.

What I have experienced has moved me powerfully. I learned from testimony from nuclear bomb survivors (Hibakusha), technical descriptions of the events of those days, diplomatic arguments from around the world, and demonstrations of peace movements from Japan and beyond. In the aftermath of such powerful testimony, the natural conclusion is inescapable: Nuclear weapons should be made illegal, never used again, and dismantled. The wealth of resources going toward their production should instead be dedicated to programs that actually create security like education, diplomacy, material security, and cooperative institutions.

I’d like to report back what I experienced and learned for the benefit of those unfamiliar with the details of nuclear weapons control—especially those in the United States. As someone who grew up through U.S. public schools and engages with students in higher education, I can say that we are woefully ignorant of the truth. Let this correct the record and help open more eyes to the truth.

I want to share both the technical details of what happened during nuclear bomb detonation as well as testimony from those who survived the blasts, the Hibakusha. Both are difficult to read. I urge readers to open their minds and hearts and imagine to their greatest ability what those who experienced the bombings felt like as horror unfolded before their very eyes.

At the World Conference, Professor Oya Masato of the Nagasaki Institute of Applied Science shared a scientific account of the bombing of Nagasaki. This second bomb exploded at 11:02 am on August 9, 1945, 503 meters above the town of Matsuyama, about three kilometers north of Nagasaki city center. Instantly, the bomb turned into a fireball of tens of millions of degrees. The surface of the fireball cooled to approximately 7,000°C in 0.1 seconds. The ground temperature at the hypocenter (point of detonation) rose as high as 3,000-4,000°C, and humans in the area were instantly carbonized. The bomb generated a shock wave and blast which traveled at 440 meters per second at the hypocenter and 60 meters per second two kilometers away from the hypocenter. Those shock waves destroyed most of the city, an area of 405 square kilometers, within 10 seconds. Fires emerged and burned an area of 6.7 square kilometers. Thousands were instantly killed, and by the end of 1945, the death toll rose to 74,000.

This scientific description begins to describe the horrors of the bomb. But it can be hard to imagine. What stands out is the sheer power and devastation: a whole city leveled and engulfed in flames within seconds. Devastation on a scale never before seen. Callous destruction, indiscriminate murder.

What truly rends the heart is the testimony of Hibakusha, those who survived the bomb and tell their stories. The Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum depicts many such stories. It’s nearly unbearable to take in and try to imagine even a sliver of what these horrors would feel like. The stories make clear that the atomic bombs created a literal hell on Earth.

A device that can cause this amount of suffering has no place in human society.

One story, shared by a Hibakusha of Hiroshima, Park Jung-soon, 11 years old at the time, describes her experience. On the morning of the bombing, she and her six family members living together were surprised by a flash like lightning and thunder. The sky lit up. Suddenly, a blast and tremendous sound shook the whole house, lifting the entire structure upward. The house fell back down, collapsed, and crushed the family beneath it. It all happened in seconds. They could not move their bodies and thought they would die.

Imagine the sheer terror of suddenly being launched into the air only to plummet down and be crushed by your home. Imagine your home, something that we hold deep attachment to and a place of safety, comfort, and love, collapsing down on you and your whole family. In moments your safe haven becomes the source of incredible pain. Imagine those you love looking at you with the fear of death in their eyes for a split second before having your gaze ripped away by the force of crushing weight.

Jung-soon opened her eyes and found herself trapped under a thick beam. Her mother desperately pulled her out and helped her crawl out of the collapsed walls. Her head was bleeding heavily, but she rose to her feet and looked around: The house next door had fallen down as well, people were running away, crying, shouting. The village as she knew it was falling apart.

While the family fled, they saw people dead on the ground, or alive but in agony crying or shouting. People were pulling carts carrying wounded or dead neighbors. People were covered in burns and suffering in pain. She describes it as like the hell of a cartoon but in reality.

At the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, there were many such stories and testimonies, as well as photographs and artwork created by Hibakusha attempting to visually depict what they experienced. Details like those in Jung-soon’s story were common. People burned beyond recognition. Structures flattened. The dead littering the city. People walking around with flesh peeling from their bodies, literally melting off, begging and screaming for water. It was, indeed, hell on Earth.

It may be difficult, but I implore you to try to deeply imagine what these words convey. In a world where many of us are constantly exposed to language of indiscriminate violence through news media, it may be easy to simply read this and register it as fact. But try to register it as feeling. What would it feel like to feel your own broken body throb with pain while simultaneously witnessing mass death all around you? Can you imagine a human being burnt beyond recognition? Someone with their flesh melting off? The sounds of screams, crying, wailing, and pure fear were profoundly traumatizing.

The effects of nuclear weapons, the scenes described by the Hibakusha, are things that should never be visited upon this Earth. A device that can cause this amount of suffering has no place in human society.

This does not even describe the effects of the bombing that persisted long after the initial devastation. Hibakusha faced severe effects from radiation poisoning and the physical damage—burns, breakages, disfigurations—they sustained. They were also subject to discrimination for decades, as people feared contamination if they came in contact with Hibakusha. Many kept their stories secret.

These are tragic tales that the Japanese peace movement describes and uplifts for all to learn from. They have been telling their stories for nearly 80 years. It’s about time more of us listen.

In the United States, there is a profound culture of ignorance surrounding nuclear weapons. I experienced this firsthand growing up in U.S. public schools and then in collegiate engineering studies.

When I was in high school, I elected to take the upper-level U.S. history class—one which gives college credit if you do well enough. The course is infamous in American high schools: AP U.S. History, or APUSH for short. Our teacher taught out of a book used in many classrooms across the country, titled The American Pageant: A History of the Republic by Kennedy, Cohen, and Bailey. This book, like many others used in the U.S., describes the atomic bombing as the key to ending the second World War, a tough but necessary decision by President Harry Truman. The argument goes that dropping the bombs eliminated the need for a U.S. ground invasion, which would have cost half a million lives (which Howard Zinn notes in A People’s History of the United States seemed to have “been pulled out of the air to justify the bombings”). It becomes a trolly problem of sorts: Would you end 200,000 lives to save half a million?

That’s as far as we typically get in U.S. depictions of the bombings. We are stuck thinking at a high school level about nuclear weapons—in a country whose high schools are not known for their rigor or nuanced teaching of U.S. history. Now, when I teach at universities and talk with students in engineering, their understanding of the bombings is the same: an unfortunate necessity or political blunder. Even the faculty teaching the course, presumably sharp thinkers with PhDs, repeat the same lines.

Students should not be indoctrinated into a version of the story favorable to the U.S. perspective.

In popular media, the story is no different. 2023’s blockbuster Oppenheimer—which broke box office expectations and was given seven awards at the Oscars—was a shallow depiction of the events. As it told a dramatized version of Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer’s work on the Manhattan Project, it attempted to depict his inner turmoil as he grappled with visions of what must have become of victims. However, the screen time dedicated to his haunting visions does not exceed five minutes in a three-hour film.

Accurate depictions of the horrors of nuclear bombings are nowhere to be found in dominant U.S. education and media. Textbooks do not describe the detailed suffering of victims, the social discrimination they experienced afterward, or the stories of their deeply difficult lives. Films choose not to center the victims of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but rather the perpetrators. It is tragic and laughable to consider the fact that a film like Oppenheimer is praised for its critique of nuclear weapons while it entirely centers the life of the man who was instrumental in their creation rather than the lives of his victims.

Peace organizations across the U.S. are pushing against these narratives, trying to spread the truth, and fighting for nonproliferation. But without countering the widespread ignorance of our own population, we will not get far. In a world increasingly plagued by misinformation and falsehood, we have our work cut out when it comes to effectively spreading the truth about nuclear weapons. We need to dispel the veil of ignorance covering our communities if we are to build a large enough movement to push the U.S. to disarm, re-engage in treaties, and work toward peace under cooperation rather than precarious stability based on fear and threats.

One of the first steps can be to simply tell the truth. Stories matter, and how we tell the history of our own nation matters. Students should not be indoctrinated into a version of the story favorable to the U.S. perspective. Media should accurately describe the horrors. The stories of the Hibakusha should be known by everyone.