SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

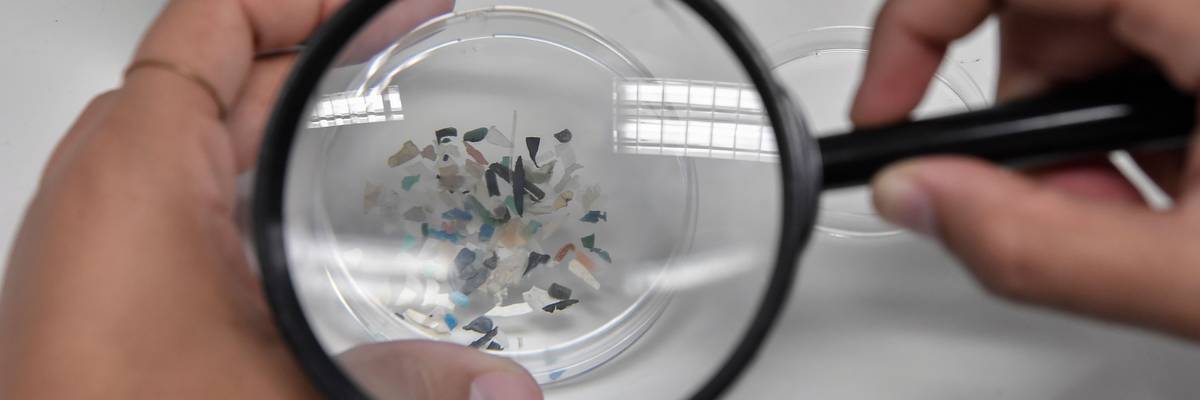

A biologist looks at microplastics found in sea species at the Hellenic Centre for Marine Research near Athens, Greece on November 26, 2019.

The biggest threat isn’t scientific uncertainty, since there’s a considerable amount of scientific consensus that there is plastic in us. The biggest threat is weaponized uncertainty used to delay regulations.

“Microplastics are everywhere, and they’re harming us.”

“Actually, maybe not.”

“Hold on, that study might be flawed.”

“Bombshell… the whole field is in doubt.”

The headline isn’t “microplastics in people might be wrong,” but rather “quantifying microplastics in human samples is challenging, and the science is evolving in the right direction.”

If you’ve been hearing about microplastics recently, you may have been getting whiplash from the headlines. But you shouldn’t be.

Because this is what science looks like when it’s working: Researchers test new ideas and challenge each other’s methods. This helps refine what we know. What isn’t supposed to happen is a normal, healthy, scientific process getting manipulated into a dramatic storyline about a fictional scandal—a story that can leave the public confused.

For over two decades, we’ve studied plastic pollution in the ocean. Scientists started describing the accumulation zones of plastic in the subtropical gyres, the places where wind and water currents concentrate floating debris. The research pointed to a truth that was complicated but clear: Most of the pieces are tiny, fragmented plastic—microplastics—along with some larger marine debris, like fishing gear.

But the media put a spin on it, and gave the world a simpler picture: a floating island of trash, “twice the size of Texas.” Some even called this a “garbage patch” you could supposedly walk on. People cried, “Why can’t I see it on Google Maps?” Some wondered if the US should plant a flag, and a handful of naive entrepreneurs fabricated fantastic ocean cleanup contraptions.

It was dramatic. Word spread. But eventually, it backfired.

All those who went looking for an island, didn’t find one. Instead they concluded, “It’s more like smog than a landfill,” and some pointed out, “Maybe it was exaggerated and the world had been duped.”

The pattern—one that goes oversimplify, sensationalize, backlash, dismissal—can drain urgency from a real crisis. Misinformation gets the headline. This gets repeated, as we’ve seen before in other environmental debates, such as the hole in the ozone layer, or climate change. The same thing is unfolding now with microplastics and human health.

The recent article in The Guardian that sparked this debate focuses on a real issue. In our research studying microplastics in the environment and animal studies, measuring micro- and nanoplastics in human tissue is incredibly hard. It is particularly difficult when researchers are looking for very small particle sizes, where laboratory contamination from airborne sources becomes harder to rule out. This is especially the case in human tissue.

Microplastics are not like other contaminants, such as lead in water, where you can measure parts per billion, and lean on decades of standardized instruments and test methods. Plastics come in many polymers, sizes, and shapes. Nanoplastics behave differently than microplastics. And plastic is everywhere, meaning background contamination is always a risk. This is sometimes called the “pig pen effect”—it is a challenge to study a material that is so widespread.

The Guardian article is not a devastating blow. It’s a scientific debate around specific methods in a research field that is rapidly improving.

The headline isn’t “microplastics in people might be wrong,” but rather “quantifying microplastics in human samples is challenging, and the science is evolving in the right direction.”

That difference matters. If the public hears “doubt cast,” then it translates it as “maybe plastic pollution isn’t really there or not that bad.” The question is, does it hold up across methods, across labs, across time?

So what has science taught us?

The biggest threat here isn’t scientific uncertainty, since there’s a considerable amount of scientific consensus that there is plastic in us. The biggest threat is weaponized uncertainty.

Environmental health has a predictable plot—when evidence starts piling up that a pollutant is harmful, a well-funded countermovement doesn’t always try to prove it’s safe. On the contrary, it tries to prove that the science is messy, uncertain, and “we need more data.”.

We’re not asking journalists to avoid urgency. Plastic pollution is urgent. Certain phrases, however, may signal that you’re being pulled into a pattern of mythmaking.

The industry has a playbook with favorite phrases, such as: “not conclusive,” “uncertain,” “scientists disagree,” “lack of consensus.” Disagreement in science is healthy. However, this (very routine) component of science can also become a winning political strategy used against science and public policy. Casting doubt can delay regulation.

Naomi Oreskes writes in Merchants of Doubt, “The industry had realized you could create the impression of controversy simply by asking questions.” That’s why our concern isn’t that researchers are debating methods. Our concern is that sensational headlines can warp debate, and give merchants of doubt an opportunity to skew public perception.

We’re not asking journalists to avoid urgency. Plastic pollution is urgent. Certain phrases, however, may signal that you’re being pulled into a pattern of mythmaking, such as “bombshell,” or “debunked,” when what’s really happening is refinement. Those phrases shock and entertain, but do little to foster understanding.

What we actually need next is for the microplastics field to keep growing. Researchers across the board—from those that think studies are exaggerated to those that stand behind their research findings—are making calls for better lab protocols, contamination controls, reporting requirements, and inter-lab studies to validate results. These are unglamorous, but they’re what solidify early research findings into trusted science. A first-of-its-kind finding of plastic somewhere in the human body shouldn’t be framed like the final truth. It should be heralded as the beginning of a more complete picture.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

“Microplastics are everywhere, and they’re harming us.”

“Actually, maybe not.”

“Hold on, that study might be flawed.”

“Bombshell… the whole field is in doubt.”

The headline isn’t “microplastics in people might be wrong,” but rather “quantifying microplastics in human samples is challenging, and the science is evolving in the right direction.”

If you’ve been hearing about microplastics recently, you may have been getting whiplash from the headlines. But you shouldn’t be.

Because this is what science looks like when it’s working: Researchers test new ideas and challenge each other’s methods. This helps refine what we know. What isn’t supposed to happen is a normal, healthy, scientific process getting manipulated into a dramatic storyline about a fictional scandal—a story that can leave the public confused.

For over two decades, we’ve studied plastic pollution in the ocean. Scientists started describing the accumulation zones of plastic in the subtropical gyres, the places where wind and water currents concentrate floating debris. The research pointed to a truth that was complicated but clear: Most of the pieces are tiny, fragmented plastic—microplastics—along with some larger marine debris, like fishing gear.

But the media put a spin on it, and gave the world a simpler picture: a floating island of trash, “twice the size of Texas.” Some even called this a “garbage patch” you could supposedly walk on. People cried, “Why can’t I see it on Google Maps?” Some wondered if the US should plant a flag, and a handful of naive entrepreneurs fabricated fantastic ocean cleanup contraptions.

It was dramatic. Word spread. But eventually, it backfired.

All those who went looking for an island, didn’t find one. Instead they concluded, “It’s more like smog than a landfill,” and some pointed out, “Maybe it was exaggerated and the world had been duped.”

The pattern—one that goes oversimplify, sensationalize, backlash, dismissal—can drain urgency from a real crisis. Misinformation gets the headline. This gets repeated, as we’ve seen before in other environmental debates, such as the hole in the ozone layer, or climate change. The same thing is unfolding now with microplastics and human health.

The recent article in The Guardian that sparked this debate focuses on a real issue. In our research studying microplastics in the environment and animal studies, measuring micro- and nanoplastics in human tissue is incredibly hard. It is particularly difficult when researchers are looking for very small particle sizes, where laboratory contamination from airborne sources becomes harder to rule out. This is especially the case in human tissue.

Microplastics are not like other contaminants, such as lead in water, where you can measure parts per billion, and lean on decades of standardized instruments and test methods. Plastics come in many polymers, sizes, and shapes. Nanoplastics behave differently than microplastics. And plastic is everywhere, meaning background contamination is always a risk. This is sometimes called the “pig pen effect”—it is a challenge to study a material that is so widespread.

The Guardian article is not a devastating blow. It’s a scientific debate around specific methods in a research field that is rapidly improving.

The headline isn’t “microplastics in people might be wrong,” but rather “quantifying microplastics in human samples is challenging, and the science is evolving in the right direction.”

That difference matters. If the public hears “doubt cast,” then it translates it as “maybe plastic pollution isn’t really there or not that bad.” The question is, does it hold up across methods, across labs, across time?

So what has science taught us?

The biggest threat here isn’t scientific uncertainty, since there’s a considerable amount of scientific consensus that there is plastic in us. The biggest threat is weaponized uncertainty.

Environmental health has a predictable plot—when evidence starts piling up that a pollutant is harmful, a well-funded countermovement doesn’t always try to prove it’s safe. On the contrary, it tries to prove that the science is messy, uncertain, and “we need more data.”.

We’re not asking journalists to avoid urgency. Plastic pollution is urgent. Certain phrases, however, may signal that you’re being pulled into a pattern of mythmaking.

The industry has a playbook with favorite phrases, such as: “not conclusive,” “uncertain,” “scientists disagree,” “lack of consensus.” Disagreement in science is healthy. However, this (very routine) component of science can also become a winning political strategy used against science and public policy. Casting doubt can delay regulation.

Naomi Oreskes writes in Merchants of Doubt, “The industry had realized you could create the impression of controversy simply by asking questions.” That’s why our concern isn’t that researchers are debating methods. Our concern is that sensational headlines can warp debate, and give merchants of doubt an opportunity to skew public perception.

We’re not asking journalists to avoid urgency. Plastic pollution is urgent. Certain phrases, however, may signal that you’re being pulled into a pattern of mythmaking, such as “bombshell,” or “debunked,” when what’s really happening is refinement. Those phrases shock and entertain, but do little to foster understanding.

What we actually need next is for the microplastics field to keep growing. Researchers across the board—from those that think studies are exaggerated to those that stand behind their research findings—are making calls for better lab protocols, contamination controls, reporting requirements, and inter-lab studies to validate results. These are unglamorous, but they’re what solidify early research findings into trusted science. A first-of-its-kind finding of plastic somewhere in the human body shouldn’t be framed like the final truth. It should be heralded as the beginning of a more complete picture.

“Microplastics are everywhere, and they’re harming us.”

“Actually, maybe not.”

“Hold on, that study might be flawed.”

“Bombshell… the whole field is in doubt.”

The headline isn’t “microplastics in people might be wrong,” but rather “quantifying microplastics in human samples is challenging, and the science is evolving in the right direction.”

If you’ve been hearing about microplastics recently, you may have been getting whiplash from the headlines. But you shouldn’t be.

Because this is what science looks like when it’s working: Researchers test new ideas and challenge each other’s methods. This helps refine what we know. What isn’t supposed to happen is a normal, healthy, scientific process getting manipulated into a dramatic storyline about a fictional scandal—a story that can leave the public confused.

For over two decades, we’ve studied plastic pollution in the ocean. Scientists started describing the accumulation zones of plastic in the subtropical gyres, the places where wind and water currents concentrate floating debris. The research pointed to a truth that was complicated but clear: Most of the pieces are tiny, fragmented plastic—microplastics—along with some larger marine debris, like fishing gear.

But the media put a spin on it, and gave the world a simpler picture: a floating island of trash, “twice the size of Texas.” Some even called this a “garbage patch” you could supposedly walk on. People cried, “Why can’t I see it on Google Maps?” Some wondered if the US should plant a flag, and a handful of naive entrepreneurs fabricated fantastic ocean cleanup contraptions.

It was dramatic. Word spread. But eventually, it backfired.

All those who went looking for an island, didn’t find one. Instead they concluded, “It’s more like smog than a landfill,” and some pointed out, “Maybe it was exaggerated and the world had been duped.”

The pattern—one that goes oversimplify, sensationalize, backlash, dismissal—can drain urgency from a real crisis. Misinformation gets the headline. This gets repeated, as we’ve seen before in other environmental debates, such as the hole in the ozone layer, or climate change. The same thing is unfolding now with microplastics and human health.

The recent article in The Guardian that sparked this debate focuses on a real issue. In our research studying microplastics in the environment and animal studies, measuring micro- and nanoplastics in human tissue is incredibly hard. It is particularly difficult when researchers are looking for very small particle sizes, where laboratory contamination from airborne sources becomes harder to rule out. This is especially the case in human tissue.

Microplastics are not like other contaminants, such as lead in water, where you can measure parts per billion, and lean on decades of standardized instruments and test methods. Plastics come in many polymers, sizes, and shapes. Nanoplastics behave differently than microplastics. And plastic is everywhere, meaning background contamination is always a risk. This is sometimes called the “pig pen effect”—it is a challenge to study a material that is so widespread.

The Guardian article is not a devastating blow. It’s a scientific debate around specific methods in a research field that is rapidly improving.

The headline isn’t “microplastics in people might be wrong,” but rather “quantifying microplastics in human samples is challenging, and the science is evolving in the right direction.”

That difference matters. If the public hears “doubt cast,” then it translates it as “maybe plastic pollution isn’t really there or not that bad.” The question is, does it hold up across methods, across labs, across time?

So what has science taught us?

The biggest threat here isn’t scientific uncertainty, since there’s a considerable amount of scientific consensus that there is plastic in us. The biggest threat is weaponized uncertainty.

Environmental health has a predictable plot—when evidence starts piling up that a pollutant is harmful, a well-funded countermovement doesn’t always try to prove it’s safe. On the contrary, it tries to prove that the science is messy, uncertain, and “we need more data.”.

We’re not asking journalists to avoid urgency. Plastic pollution is urgent. Certain phrases, however, may signal that you’re being pulled into a pattern of mythmaking.

The industry has a playbook with favorite phrases, such as: “not conclusive,” “uncertain,” “scientists disagree,” “lack of consensus.” Disagreement in science is healthy. However, this (very routine) component of science can also become a winning political strategy used against science and public policy. Casting doubt can delay regulation.

Naomi Oreskes writes in Merchants of Doubt, “The industry had realized you could create the impression of controversy simply by asking questions.” That’s why our concern isn’t that researchers are debating methods. Our concern is that sensational headlines can warp debate, and give merchants of doubt an opportunity to skew public perception.

We’re not asking journalists to avoid urgency. Plastic pollution is urgent. Certain phrases, however, may signal that you’re being pulled into a pattern of mythmaking, such as “bombshell,” or “debunked,” when what’s really happening is refinement. Those phrases shock and entertain, but do little to foster understanding.

What we actually need next is for the microplastics field to keep growing. Researchers across the board—from those that think studies are exaggerated to those that stand behind their research findings—are making calls for better lab protocols, contamination controls, reporting requirements, and inter-lab studies to validate results. These are unglamorous, but they’re what solidify early research findings into trusted science. A first-of-its-kind finding of plastic somewhere in the human body shouldn’t be framed like the final truth. It should be heralded as the beginning of a more complete picture.