SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

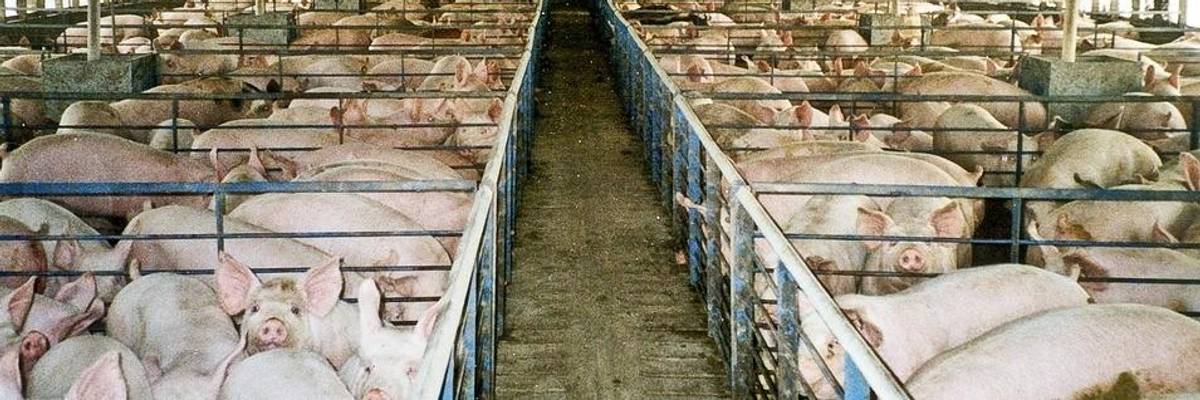

Excruciating industry-standard abuses, such as beak trimming and tail docking, and overcrowded and unsanitary conditions suppress animals' immune systems and create the perfect breeding ground for diseases that pose an existential threat to humanity. (Photo: Farm Sanctuary/flickr/cc)

Every day slaughterhouse workers put their health and well-being on the line. According to the National Employment Law Project, slaughter plant jobs are among the most dangerous in the country. Now, these jobs are even more dangerous, as slaughterhouse workers find themselves standing shoulder to shoulder during a pandemic, while the rest of us are told to stand six feet apart.

Most slaughterhouse workers are people of color living in low-income communities where jobs are scarce. They often lack the necessary visas, with little to no access to legal assistance or medical care when abuses or injuries occur. Workers incur a wide range of physical injuries, from carpal tunnel syndrome to dismemberment, due to dizzying slaughter-line speeds and other unsafe conditions. They also suffer higher rates of several psychological disorders, including anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

COVID-19 has illuminated the inherent risks in our food system--built on the industrial-scale exploitation of humans and nonhumans alike.

And their plight is only worsening. In 2018, the U.S. Department of Agriculture issued new rules to allow poultry slaughter lines to move at an even faster pace--authorizing some slaughterhouses to increase line speeds to 175 birds per minute, nearly three birds per second. This increase not only will result in greater injury risks for employees but poses serious animal welfare concerns. The rapid pace of typical slaughter lines subjects millions of birds to extreme suffering through improper shackling and failed stunning. Many chickens are fully conscious when their throats are slit, while others--about half a million in the United States each year--are drowned in the scalding water of feather-removal tanks.

Current slaughter plant conditions pose significant threats to workers' health. Workers at a Georgia chicken slaughterhouse staged the first of several plant walkouts. "We're up here risking our life for chicken," one employee reportedly said. Around the country, workers are demanding companies implement social distancing and other measures to prevent the spread of the coronavirus.

Protecting workers from COVID-19 is just the beginning of cleaning up our food system. Foodborne illnesses also risk consumer health. Irresponsibly fast slaughter lines likely prevent detection of fecal matter and other potentially dangerous substances on carcasses. A 2014 Consumer Reports study found that 97 percent of chicken breasts sampled contained potentially lethal bacteria. In fact, foodborne pathogens originating in animals kill thousands globally each year, and scientists predict that they will continue to cause outbreaks and deaths throughout the world.

But the public health risks don't arise only at the slaughterhouse. The vast majority of animals killed for food are raised in factory farms: industrial warehouses where animals are packed by the thousands or tens of thousands and forced to live in their own waste. Excruciating industry-standard abuses, such as beak trimming and tail docking, and overcrowded and unsanitary conditions suppress animals' immune systems and create the perfect breeding ground for diseases that pose an existential threat to humanity. Though COVID-19 likely originated in wild species, we know that other pandemics, such as swine flu and bird flu, did originate in animals more typically raised for food: pigs and chickens, respectively.

These weaknesses in our food system indicate urgent change is needed to protect workers, consumers, animals, and public health. Some companies are taking measures to give workers more space to practice social distancing. These measures exemplify immediate actions that all meat producers must take to protect the health and safety of their workers. Other remedies include hazard pay for the duration of the pandemic and paid sick leave. In the long run, companies must permanently slow line speeds and invest in a controlled-atmosphere stunning (CAS) system that protects workers, improves animal welfare, and safeguards public health. Companies like Perdue are already using CAS in some of their facilities, and Tyson Foods is testing a CAS system.

COVID-19 has illuminated the inherent risks in our food system--built on the industrial-scale exploitation of humans and nonhumans alike. Addressing these flaws starts with choosing more plant-based foods and pressuring meat producers and regulatory agencies to protect workers and animals. We can reform our food system but only if we put the most vulnerable first.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Every day slaughterhouse workers put their health and well-being on the line. According to the National Employment Law Project, slaughter plant jobs are among the most dangerous in the country. Now, these jobs are even more dangerous, as slaughterhouse workers find themselves standing shoulder to shoulder during a pandemic, while the rest of us are told to stand six feet apart.

Most slaughterhouse workers are people of color living in low-income communities where jobs are scarce. They often lack the necessary visas, with little to no access to legal assistance or medical care when abuses or injuries occur. Workers incur a wide range of physical injuries, from carpal tunnel syndrome to dismemberment, due to dizzying slaughter-line speeds and other unsafe conditions. They also suffer higher rates of several psychological disorders, including anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

COVID-19 has illuminated the inherent risks in our food system--built on the industrial-scale exploitation of humans and nonhumans alike.

And their plight is only worsening. In 2018, the U.S. Department of Agriculture issued new rules to allow poultry slaughter lines to move at an even faster pace--authorizing some slaughterhouses to increase line speeds to 175 birds per minute, nearly three birds per second. This increase not only will result in greater injury risks for employees but poses serious animal welfare concerns. The rapid pace of typical slaughter lines subjects millions of birds to extreme suffering through improper shackling and failed stunning. Many chickens are fully conscious when their throats are slit, while others--about half a million in the United States each year--are drowned in the scalding water of feather-removal tanks.

Current slaughter plant conditions pose significant threats to workers' health. Workers at a Georgia chicken slaughterhouse staged the first of several plant walkouts. "We're up here risking our life for chicken," one employee reportedly said. Around the country, workers are demanding companies implement social distancing and other measures to prevent the spread of the coronavirus.

Protecting workers from COVID-19 is just the beginning of cleaning up our food system. Foodborne illnesses also risk consumer health. Irresponsibly fast slaughter lines likely prevent detection of fecal matter and other potentially dangerous substances on carcasses. A 2014 Consumer Reports study found that 97 percent of chicken breasts sampled contained potentially lethal bacteria. In fact, foodborne pathogens originating in animals kill thousands globally each year, and scientists predict that they will continue to cause outbreaks and deaths throughout the world.

But the public health risks don't arise only at the slaughterhouse. The vast majority of animals killed for food are raised in factory farms: industrial warehouses where animals are packed by the thousands or tens of thousands and forced to live in their own waste. Excruciating industry-standard abuses, such as beak trimming and tail docking, and overcrowded and unsanitary conditions suppress animals' immune systems and create the perfect breeding ground for diseases that pose an existential threat to humanity. Though COVID-19 likely originated in wild species, we know that other pandemics, such as swine flu and bird flu, did originate in animals more typically raised for food: pigs and chickens, respectively.

These weaknesses in our food system indicate urgent change is needed to protect workers, consumers, animals, and public health. Some companies are taking measures to give workers more space to practice social distancing. These measures exemplify immediate actions that all meat producers must take to protect the health and safety of their workers. Other remedies include hazard pay for the duration of the pandemic and paid sick leave. In the long run, companies must permanently slow line speeds and invest in a controlled-atmosphere stunning (CAS) system that protects workers, improves animal welfare, and safeguards public health. Companies like Perdue are already using CAS in some of their facilities, and Tyson Foods is testing a CAS system.

COVID-19 has illuminated the inherent risks in our food system--built on the industrial-scale exploitation of humans and nonhumans alike. Addressing these flaws starts with choosing more plant-based foods and pressuring meat producers and regulatory agencies to protect workers and animals. We can reform our food system but only if we put the most vulnerable first.

Every day slaughterhouse workers put their health and well-being on the line. According to the National Employment Law Project, slaughter plant jobs are among the most dangerous in the country. Now, these jobs are even more dangerous, as slaughterhouse workers find themselves standing shoulder to shoulder during a pandemic, while the rest of us are told to stand six feet apart.

Most slaughterhouse workers are people of color living in low-income communities where jobs are scarce. They often lack the necessary visas, with little to no access to legal assistance or medical care when abuses or injuries occur. Workers incur a wide range of physical injuries, from carpal tunnel syndrome to dismemberment, due to dizzying slaughter-line speeds and other unsafe conditions. They also suffer higher rates of several psychological disorders, including anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

COVID-19 has illuminated the inherent risks in our food system--built on the industrial-scale exploitation of humans and nonhumans alike.

And their plight is only worsening. In 2018, the U.S. Department of Agriculture issued new rules to allow poultry slaughter lines to move at an even faster pace--authorizing some slaughterhouses to increase line speeds to 175 birds per minute, nearly three birds per second. This increase not only will result in greater injury risks for employees but poses serious animal welfare concerns. The rapid pace of typical slaughter lines subjects millions of birds to extreme suffering through improper shackling and failed stunning. Many chickens are fully conscious when their throats are slit, while others--about half a million in the United States each year--are drowned in the scalding water of feather-removal tanks.

Current slaughter plant conditions pose significant threats to workers' health. Workers at a Georgia chicken slaughterhouse staged the first of several plant walkouts. "We're up here risking our life for chicken," one employee reportedly said. Around the country, workers are demanding companies implement social distancing and other measures to prevent the spread of the coronavirus.

Protecting workers from COVID-19 is just the beginning of cleaning up our food system. Foodborne illnesses also risk consumer health. Irresponsibly fast slaughter lines likely prevent detection of fecal matter and other potentially dangerous substances on carcasses. A 2014 Consumer Reports study found that 97 percent of chicken breasts sampled contained potentially lethal bacteria. In fact, foodborne pathogens originating in animals kill thousands globally each year, and scientists predict that they will continue to cause outbreaks and deaths throughout the world.

But the public health risks don't arise only at the slaughterhouse. The vast majority of animals killed for food are raised in factory farms: industrial warehouses where animals are packed by the thousands or tens of thousands and forced to live in their own waste. Excruciating industry-standard abuses, such as beak trimming and tail docking, and overcrowded and unsanitary conditions suppress animals' immune systems and create the perfect breeding ground for diseases that pose an existential threat to humanity. Though COVID-19 likely originated in wild species, we know that other pandemics, such as swine flu and bird flu, did originate in animals more typically raised for food: pigs and chickens, respectively.

These weaknesses in our food system indicate urgent change is needed to protect workers, consumers, animals, and public health. Some companies are taking measures to give workers more space to practice social distancing. These measures exemplify immediate actions that all meat producers must take to protect the health and safety of their workers. Other remedies include hazard pay for the duration of the pandemic and paid sick leave. In the long run, companies must permanently slow line speeds and invest in a controlled-atmosphere stunning (CAS) system that protects workers, improves animal welfare, and safeguards public health. Companies like Perdue are already using CAS in some of their facilities, and Tyson Foods is testing a CAS system.

COVID-19 has illuminated the inherent risks in our food system--built on the industrial-scale exploitation of humans and nonhumans alike. Addressing these flaws starts with choosing more plant-based foods and pressuring meat producers and regulatory agencies to protect workers and animals. We can reform our food system but only if we put the most vulnerable first.