SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

The top one-tenth of 1 percent controls as much wealth as the bottom 90 percent, while roughly a fifth of American children live in poverty, and half of American infants are so poor they depend on public aid to eat.(Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Images)

It's easy to feel fatalistic, accepting as "just the way things are" an America in which the top one-tenth of 1 percent controls as much wealth as the bottom 90 percent, while roughly a fifth of American children live in poverty, and half of American infants are so poor they depend on public aid to eat.

But wait.

What if we were to acknowledge -- to really let sink in -- that we have arrived at this tragic place in no time at all, historically speaking? Might we even feel entitled to hope and thus motivated to work for transformational shift of the kind the Green New Deal now envisions? One in which we effectively address climate change as we also tackle economic inequity?

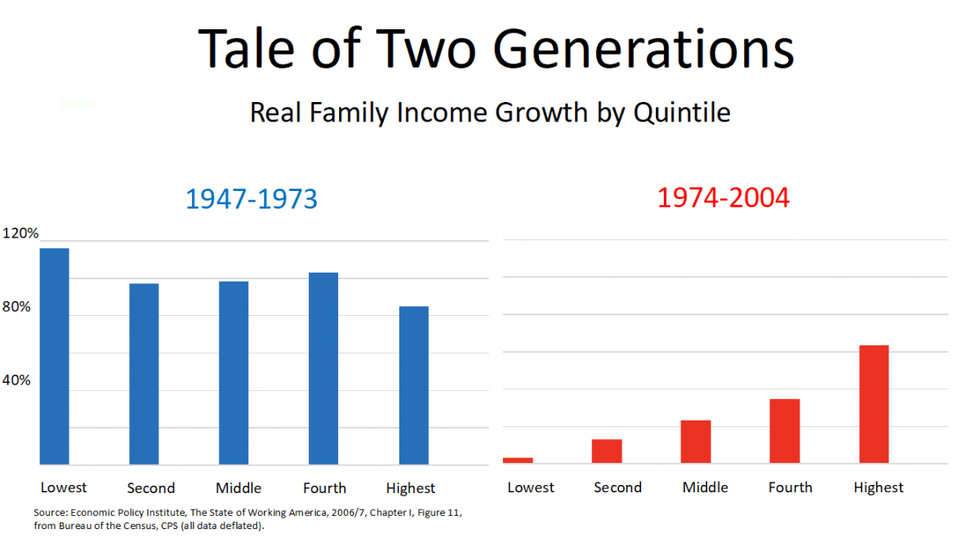

First, though, check out the chart below:

In ten columns is the tale of two generations. The blue bars capture the late 1940s through the early '70s when real family income roughly doubled for every income quintile, with the poor gaining the most.

Then...whoa! From the early '70s through the early 2000s, progress slows radically and the pattern of who gains most reverses: The richest score big time, while the poorest advance virtually not at all. Such dramatically deepening inequality has continued to worsen, not only reducing economic opportunities but shortening lives as well: The life-span gap between the richest and poorest American males is 15 years, and in recent years, overall longevity has declined.

The contrasts between these two generations is staggering; but now consider an international comparison that might strike some as yet more shocking. America, long-perceived as a paragon of "middle class" prosperity, now ranks by family income as more extreme than over 100 countries, from Russia to Bangladesh to the Democratic Republic of the Congo, according to the CIA World Factbook.

These contrasts alone should signal the truth that there is nothing inevitable about this disgrace. Not long ago we experienced more equitable income growth, linked to much greater prosperity. So, what happened to us?

Most important, our beliefs changed -- or rather, they were changed. We humans are creatures of the mind. We create our world according to what we believe is both right and possible, and our ideas, absorbed via story, create filters through which we see. So "believing is seeing," not the other way around. Both Plato and the Hopi Indians are credited with noting, "those who tell the story rule the world"; and in these two periods, different storytellers told very different stories.

In the first period (blue bars), Americans absorbed the notion that we could all advance together -- that government was established to support the "general welfare." After all, that is what our constitution's preamble affirms as a purpose of our government.

The first period benefited from FDR's New Deal that catalyzed sweeping gains for all Americans -- from establishing the minimum wage and Social Security, to strengthening workers' rights to organize, to bolstering banking industry rules. Well into mid-century, both Republicans and Democrats embraced government as a partner in setting standards and expanding opportunity.

Republican Dwight Eisenhower ran on a platform that included the pledge to "more effectively protect the rights of labor unions" and to "assure equal pay for equal work regardless of sex"; Democrat Lyndon Johnson launched the War on Poverty, which helped cut the poverty rate almost in half between 1959 and 1969; and Republican Richard Nixon signed the Clean Air act into law in 1970.

But soon, the business community feared it was losing ground and began actively, and effectively, putting forth an opposing story, as laid out in Jane Mayer's Dark Money. In 1971, the Chamber of Commerce commissioned a corporate lawyer, Lewis Powell, to prepare a game plan, known now as the "Powell Memo," for regaining ground for business. Soon thereafter, in 1977, Ronald Reagan warned Americans to "use the vitality and the magic of the marketplace to save this way of life." And by 1981, he famously declared, "in this present crisis, government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem."

In the ensuing decades, the story that a market freed from government tampering would bring prosperity for all was propagated through big-money-funded think tanks, politicians, the media, and educational materials, from grade school to graduate school.

Legislation and court decisions have weakened protections, making it harder, for example, for labor to organize. In the 1960s, about a third of workers were union members, but today this figure is less than 10 percent. And since 1968, when our minimum wage was $8.68 (in 2016 adjusted dollars), its purchasing power has fallen by 16 percent. Safety nets were tattered, too, as Bill Clinton's welfare reform ended "welfare as we know it."

We often hear the reversal of the second period blamed on job-killing technology and "globalization" in which corporations shift operations, and thus jobs, to low-wage countries where workers have few, if any, protections. So, of course, American workers' bargaining power eroded.

But, if true, other industrial nations' labor markets would have seen a shift of wealth to the top similar to ours. But no. Western Europe saw only a modest increase in inequality.

Today we are also told that fighting for transformative change is naive, that the Green New Deal, for example, is unrealistic because it prioritizes economic equity as integral to confronting climate change. However, Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez's brilliant video message, set in an imagined future in which we look back on successes achieved today, asks us to believe we can change this story. Showing us possibilities that can arise from a Green New Deal, she declares, "we can be anything we have the power to see."

Looking back now on the "tale of two generations," it's clear that when we Americans have acted from the premise of connected fates and have stayed true to our constitution's mandate to promote the "general welfare," we have accomplished what was before believed to be impossible.

Indeed, given America's revolutionary birth, isn't transformational change our very birthright?

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

It's easy to feel fatalistic, accepting as "just the way things are" an America in which the top one-tenth of 1 percent controls as much wealth as the bottom 90 percent, while roughly a fifth of American children live in poverty, and half of American infants are so poor they depend on public aid to eat.

But wait.

What if we were to acknowledge -- to really let sink in -- that we have arrived at this tragic place in no time at all, historically speaking? Might we even feel entitled to hope and thus motivated to work for transformational shift of the kind the Green New Deal now envisions? One in which we effectively address climate change as we also tackle economic inequity?

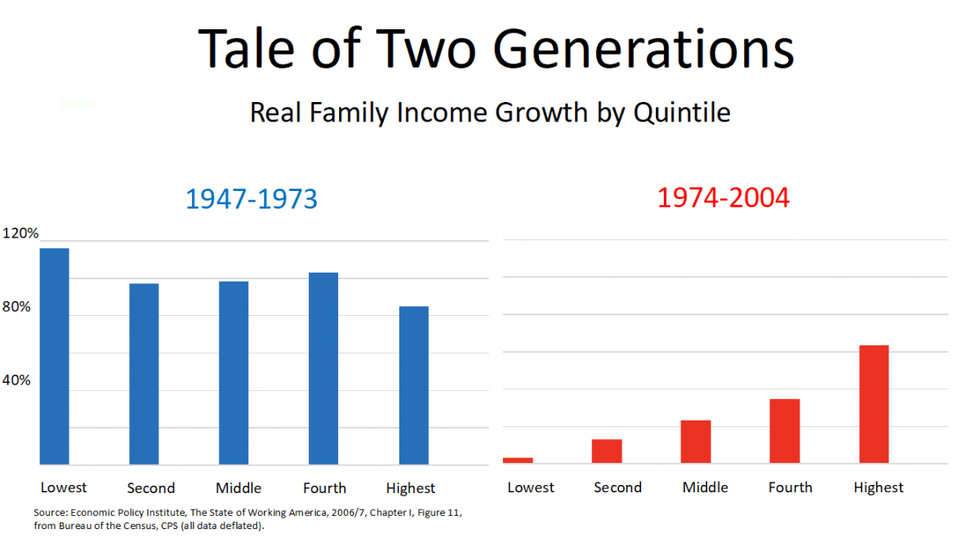

First, though, check out the chart below:

In ten columns is the tale of two generations. The blue bars capture the late 1940s through the early '70s when real family income roughly doubled for every income quintile, with the poor gaining the most.

Then...whoa! From the early '70s through the early 2000s, progress slows radically and the pattern of who gains most reverses: The richest score big time, while the poorest advance virtually not at all. Such dramatically deepening inequality has continued to worsen, not only reducing economic opportunities but shortening lives as well: The life-span gap between the richest and poorest American males is 15 years, and in recent years, overall longevity has declined.

The contrasts between these two generations is staggering; but now consider an international comparison that might strike some as yet more shocking. America, long-perceived as a paragon of "middle class" prosperity, now ranks by family income as more extreme than over 100 countries, from Russia to Bangladesh to the Democratic Republic of the Congo, according to the CIA World Factbook.

These contrasts alone should signal the truth that there is nothing inevitable about this disgrace. Not long ago we experienced more equitable income growth, linked to much greater prosperity. So, what happened to us?

Most important, our beliefs changed -- or rather, they were changed. We humans are creatures of the mind. We create our world according to what we believe is both right and possible, and our ideas, absorbed via story, create filters through which we see. So "believing is seeing," not the other way around. Both Plato and the Hopi Indians are credited with noting, "those who tell the story rule the world"; and in these two periods, different storytellers told very different stories.

In the first period (blue bars), Americans absorbed the notion that we could all advance together -- that government was established to support the "general welfare." After all, that is what our constitution's preamble affirms as a purpose of our government.

The first period benefited from FDR's New Deal that catalyzed sweeping gains for all Americans -- from establishing the minimum wage and Social Security, to strengthening workers' rights to organize, to bolstering banking industry rules. Well into mid-century, both Republicans and Democrats embraced government as a partner in setting standards and expanding opportunity.

Republican Dwight Eisenhower ran on a platform that included the pledge to "more effectively protect the rights of labor unions" and to "assure equal pay for equal work regardless of sex"; Democrat Lyndon Johnson launched the War on Poverty, which helped cut the poverty rate almost in half between 1959 and 1969; and Republican Richard Nixon signed the Clean Air act into law in 1970.

But soon, the business community feared it was losing ground and began actively, and effectively, putting forth an opposing story, as laid out in Jane Mayer's Dark Money. In 1971, the Chamber of Commerce commissioned a corporate lawyer, Lewis Powell, to prepare a game plan, known now as the "Powell Memo," for regaining ground for business. Soon thereafter, in 1977, Ronald Reagan warned Americans to "use the vitality and the magic of the marketplace to save this way of life." And by 1981, he famously declared, "in this present crisis, government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem."

In the ensuing decades, the story that a market freed from government tampering would bring prosperity for all was propagated through big-money-funded think tanks, politicians, the media, and educational materials, from grade school to graduate school.

Legislation and court decisions have weakened protections, making it harder, for example, for labor to organize. In the 1960s, about a third of workers were union members, but today this figure is less than 10 percent. And since 1968, when our minimum wage was $8.68 (in 2016 adjusted dollars), its purchasing power has fallen by 16 percent. Safety nets were tattered, too, as Bill Clinton's welfare reform ended "welfare as we know it."

We often hear the reversal of the second period blamed on job-killing technology and "globalization" in which corporations shift operations, and thus jobs, to low-wage countries where workers have few, if any, protections. So, of course, American workers' bargaining power eroded.

But, if true, other industrial nations' labor markets would have seen a shift of wealth to the top similar to ours. But no. Western Europe saw only a modest increase in inequality.

Today we are also told that fighting for transformative change is naive, that the Green New Deal, for example, is unrealistic because it prioritizes economic equity as integral to confronting climate change. However, Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez's brilliant video message, set in an imagined future in which we look back on successes achieved today, asks us to believe we can change this story. Showing us possibilities that can arise from a Green New Deal, she declares, "we can be anything we have the power to see."

Looking back now on the "tale of two generations," it's clear that when we Americans have acted from the premise of connected fates and have stayed true to our constitution's mandate to promote the "general welfare," we have accomplished what was before believed to be impossible.

Indeed, given America's revolutionary birth, isn't transformational change our very birthright?

It's easy to feel fatalistic, accepting as "just the way things are" an America in which the top one-tenth of 1 percent controls as much wealth as the bottom 90 percent, while roughly a fifth of American children live in poverty, and half of American infants are so poor they depend on public aid to eat.

But wait.

What if we were to acknowledge -- to really let sink in -- that we have arrived at this tragic place in no time at all, historically speaking? Might we even feel entitled to hope and thus motivated to work for transformational shift of the kind the Green New Deal now envisions? One in which we effectively address climate change as we also tackle economic inequity?

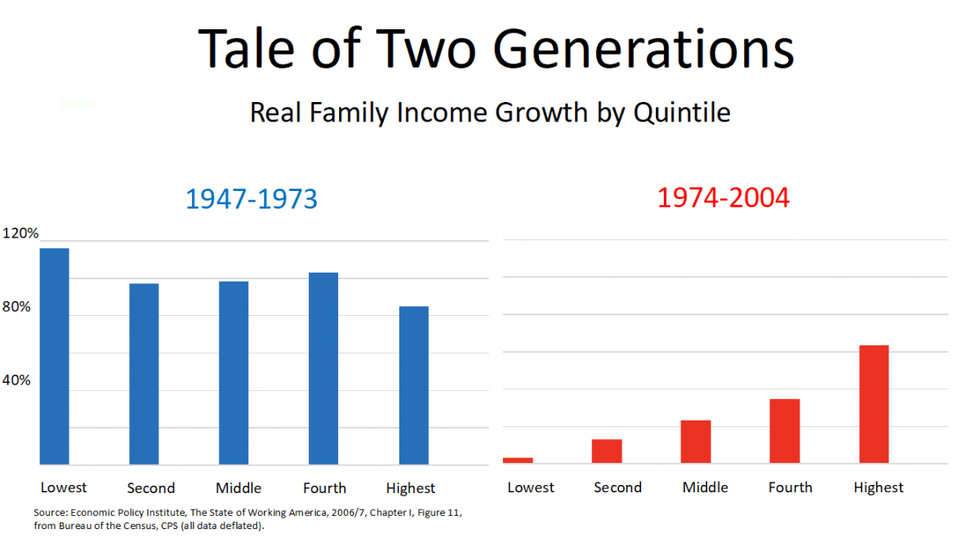

First, though, check out the chart below:

In ten columns is the tale of two generations. The blue bars capture the late 1940s through the early '70s when real family income roughly doubled for every income quintile, with the poor gaining the most.

Then...whoa! From the early '70s through the early 2000s, progress slows radically and the pattern of who gains most reverses: The richest score big time, while the poorest advance virtually not at all. Such dramatically deepening inequality has continued to worsen, not only reducing economic opportunities but shortening lives as well: The life-span gap between the richest and poorest American males is 15 years, and in recent years, overall longevity has declined.

The contrasts between these two generations is staggering; but now consider an international comparison that might strike some as yet more shocking. America, long-perceived as a paragon of "middle class" prosperity, now ranks by family income as more extreme than over 100 countries, from Russia to Bangladesh to the Democratic Republic of the Congo, according to the CIA World Factbook.

These contrasts alone should signal the truth that there is nothing inevitable about this disgrace. Not long ago we experienced more equitable income growth, linked to much greater prosperity. So, what happened to us?

Most important, our beliefs changed -- or rather, they were changed. We humans are creatures of the mind. We create our world according to what we believe is both right and possible, and our ideas, absorbed via story, create filters through which we see. So "believing is seeing," not the other way around. Both Plato and the Hopi Indians are credited with noting, "those who tell the story rule the world"; and in these two periods, different storytellers told very different stories.

In the first period (blue bars), Americans absorbed the notion that we could all advance together -- that government was established to support the "general welfare." After all, that is what our constitution's preamble affirms as a purpose of our government.

The first period benefited from FDR's New Deal that catalyzed sweeping gains for all Americans -- from establishing the minimum wage and Social Security, to strengthening workers' rights to organize, to bolstering banking industry rules. Well into mid-century, both Republicans and Democrats embraced government as a partner in setting standards and expanding opportunity.

Republican Dwight Eisenhower ran on a platform that included the pledge to "more effectively protect the rights of labor unions" and to "assure equal pay for equal work regardless of sex"; Democrat Lyndon Johnson launched the War on Poverty, which helped cut the poverty rate almost in half between 1959 and 1969; and Republican Richard Nixon signed the Clean Air act into law in 1970.

But soon, the business community feared it was losing ground and began actively, and effectively, putting forth an opposing story, as laid out in Jane Mayer's Dark Money. In 1971, the Chamber of Commerce commissioned a corporate lawyer, Lewis Powell, to prepare a game plan, known now as the "Powell Memo," for regaining ground for business. Soon thereafter, in 1977, Ronald Reagan warned Americans to "use the vitality and the magic of the marketplace to save this way of life." And by 1981, he famously declared, "in this present crisis, government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem."

In the ensuing decades, the story that a market freed from government tampering would bring prosperity for all was propagated through big-money-funded think tanks, politicians, the media, and educational materials, from grade school to graduate school.

Legislation and court decisions have weakened protections, making it harder, for example, for labor to organize. In the 1960s, about a third of workers were union members, but today this figure is less than 10 percent. And since 1968, when our minimum wage was $8.68 (in 2016 adjusted dollars), its purchasing power has fallen by 16 percent. Safety nets were tattered, too, as Bill Clinton's welfare reform ended "welfare as we know it."

We often hear the reversal of the second period blamed on job-killing technology and "globalization" in which corporations shift operations, and thus jobs, to low-wage countries where workers have few, if any, protections. So, of course, American workers' bargaining power eroded.

But, if true, other industrial nations' labor markets would have seen a shift of wealth to the top similar to ours. But no. Western Europe saw only a modest increase in inequality.

Today we are also told that fighting for transformative change is naive, that the Green New Deal, for example, is unrealistic because it prioritizes economic equity as integral to confronting climate change. However, Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez's brilliant video message, set in an imagined future in which we look back on successes achieved today, asks us to believe we can change this story. Showing us possibilities that can arise from a Green New Deal, she declares, "we can be anything we have the power to see."

Looking back now on the "tale of two generations," it's clear that when we Americans have acted from the premise of connected fates and have stayed true to our constitution's mandate to promote the "general welfare," we have accomplished what was before believed to be impossible.

Indeed, given America's revolutionary birth, isn't transformational change our very birthright?