SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

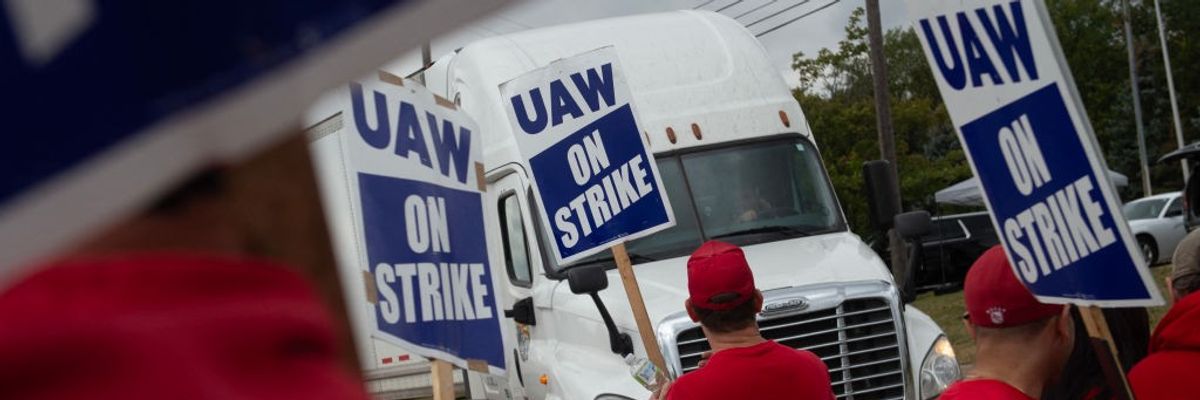

Members of the United Auto Workers (UAW) pickett outside of the Michigan Parts Assembly Plant in Wayne, Michigan amid rumors that US President Joe Biden may stop by during his visit to Michigan to stand on the pickett lines with UAW workers in Detroit, Michigan on September 26, 2023.

Progressive economic ideas have been on the whole an anathema to the U.S. political establishment and violence against labor militancy has always been the norm for almost all of the country’s political history. Nonetheless, the U.S. labor movement has not yet been defeated.

May 1st is International Workers’ Day and was established as such in celebration of the struggle for the introduction of the eight-hour workday and in memory of Chicago’s Haymarket Affair, which took place in 1886. May 1st is celebrated in over 160 countries with large-scale marches and protests as workers across the globe continue to fight for better working conditions, fair wages, and other labor rights. International Workers’ Day, however, is not celebrated in the U.S. and has in fact been practically erased from historical memory. But this shouldn’t be surprising since U.S. capitalism operates on the basis of a brutal economy where maximization of profit takes priority over everything else, including the environment and even human lives.

Indeed, the U.S. has a notorious record when it comes to worker rights. The country has the most violent and bloody history of labor relations in the advanced industrialized world, according to labor historians. Subsequently, unionization has always faced an uphill battle as corporations are allowed to engage in widespread union-busting practices through manipulation or violation of federal labor law. The recent activities of Amazon and Starbucks speak volumes of the anti-union mentality that pervades most U.S. corporations. Accordingly, unionization in the U.S. has been on decline for decades even though the majority of Americans see this development as a bad thing.

The backlash against unionization and worker rights in general in the U.S. also takes place against the backdrop of an insidious ideological framework in which it has been regarded as a self-evident truth that individuals are responsible for their own fate and that government should not interfere with the free market out of concern for social and economic inequalities.

While May Day may have been formally obliterated by the powers that be from U.S. public awareness, the labor movement is still alive and kicking.

Social Darwinism first appeared in U.S. political and social thought in the mid-1860s, as historian Richard Hofstadter showed in his brilliant work Social Darwinism in American Thought, 1860-1915, but it would be a gross mistake to think that it ever went away. The conservative counterrevolution launched by Ronald Reagan in the early 1980s and refined by Bill Clinton in the early 1990s aimed at bringing back the loathsome idea that the government should not interfere in the “survival of the fittest” by helping the weak and the poor. Progressive economic ideas have been on the whole an anathema to the U.S. political establishment and violence against labor militancy has always been the norm for almost all of the country’s political history.

Long before the movement for an eight-hour workday in the U.S., which can be largely attributed to the influx of European immigrants mainly from Italy and Germany, radicalism had set foot across a number of post-colonial states. Rhode Island, often referred to as the Rogue Island, had one of the most radical economic policies on revolutionary debt, which was wildly popular with farmers and common folks in general, and experimented with the idea of radical democracy. At approximately the same time, Shays’ rebellion in Massachusetts was also about money, debts, poverty, and democracy. Naturally, the elite in both states pulled out all stops to put an end to radicalism, and the pattern of suppressing popular demands has somehow survived in U.S. politics across time.

The pattern of suppressing social and political movements from below continued well into modern times. The Red Scare, climaxed in the late 1910s on account of the Russian revolution and the rise of labor strikes and then renewed with the anti-communist campaign of the 1940s, played a crucial role in the establishment’s fervent dedication to crushing radicalism in the U.S. and putting an end to challenges against capitalism.

In light of this, it is nothing short of a shame that May Day has been all but forgotten in U.S. political culture even though the day traces its origins to the fight of American laborers for a shorter workday.

Last year, after marching on May Day with thousands of other people in the streets of Dublin, one of the questions that was posed to me was how could it be that International Workers’ Day is not celebrated in the U.S. I am still struggling to come up with a convincing explanation, as may be evident from this essay, but Gore Vidal was not off the mark when he said, “we are the United States of Amnesia.”

Nonetheless, the U.S. labor movement has not yet been defeated and is surely not dead. In spite of the bloody suppression and the constant intimidation over many decades, the U.S. labor movement has made its presence felt on numerous historic occasions, from the Battle of Cripple Creek in 1894 and the 1892 Homestead Strike in Pennsylvania to being behind the historic 1963 march on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, and continues doing so down to this day. Scores of victories for the working class were achieved last year—and all against prevailing odds. Moreover, in 2023, labor strikes in the U.S. jumped to a 23-year high and some of the largest labor disputes in the history of the U.S. were also recorded last year.

So, while May Day may have been formally obliterated by the powers that be from U.S. public awareness, the labor movement is still alive and kicking. Even a small victory is still a victory, though time will tell of the historic significance of each step forward. Indeed, it is highly unlikely that the unionists, socialists, and anarchists that made Chicago in 1886 the center of the national movement for the eight-hour workday had foreseen what the impact of their actions would be in the struggle of the international labor movement for democracy, better wages, safer working conditions, and freedom of speech. All these social rights have been amplified over time, though much remains to be accomplished and the struggle continues.

But this is all the more reason why we must not forget—and indeed celebrate every year with marches and protests—May 1st.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

May 1st is International Workers’ Day and was established as such in celebration of the struggle for the introduction of the eight-hour workday and in memory of Chicago’s Haymarket Affair, which took place in 1886. May 1st is celebrated in over 160 countries with large-scale marches and protests as workers across the globe continue to fight for better working conditions, fair wages, and other labor rights. International Workers’ Day, however, is not celebrated in the U.S. and has in fact been practically erased from historical memory. But this shouldn’t be surprising since U.S. capitalism operates on the basis of a brutal economy where maximization of profit takes priority over everything else, including the environment and even human lives.

Indeed, the U.S. has a notorious record when it comes to worker rights. The country has the most violent and bloody history of labor relations in the advanced industrialized world, according to labor historians. Subsequently, unionization has always faced an uphill battle as corporations are allowed to engage in widespread union-busting practices through manipulation or violation of federal labor law. The recent activities of Amazon and Starbucks speak volumes of the anti-union mentality that pervades most U.S. corporations. Accordingly, unionization in the U.S. has been on decline for decades even though the majority of Americans see this development as a bad thing.

The backlash against unionization and worker rights in general in the U.S. also takes place against the backdrop of an insidious ideological framework in which it has been regarded as a self-evident truth that individuals are responsible for their own fate and that government should not interfere with the free market out of concern for social and economic inequalities.

While May Day may have been formally obliterated by the powers that be from U.S. public awareness, the labor movement is still alive and kicking.

Social Darwinism first appeared in U.S. political and social thought in the mid-1860s, as historian Richard Hofstadter showed in his brilliant work Social Darwinism in American Thought, 1860-1915, but it would be a gross mistake to think that it ever went away. The conservative counterrevolution launched by Ronald Reagan in the early 1980s and refined by Bill Clinton in the early 1990s aimed at bringing back the loathsome idea that the government should not interfere in the “survival of the fittest” by helping the weak and the poor. Progressive economic ideas have been on the whole an anathema to the U.S. political establishment and violence against labor militancy has always been the norm for almost all of the country’s political history.

Long before the movement for an eight-hour workday in the U.S., which can be largely attributed to the influx of European immigrants mainly from Italy and Germany, radicalism had set foot across a number of post-colonial states. Rhode Island, often referred to as the Rogue Island, had one of the most radical economic policies on revolutionary debt, which was wildly popular with farmers and common folks in general, and experimented with the idea of radical democracy. At approximately the same time, Shays’ rebellion in Massachusetts was also about money, debts, poverty, and democracy. Naturally, the elite in both states pulled out all stops to put an end to radicalism, and the pattern of suppressing popular demands has somehow survived in U.S. politics across time.

The pattern of suppressing social and political movements from below continued well into modern times. The Red Scare, climaxed in the late 1910s on account of the Russian revolution and the rise of labor strikes and then renewed with the anti-communist campaign of the 1940s, played a crucial role in the establishment’s fervent dedication to crushing radicalism in the U.S. and putting an end to challenges against capitalism.

In light of this, it is nothing short of a shame that May Day has been all but forgotten in U.S. political culture even though the day traces its origins to the fight of American laborers for a shorter workday.

Last year, after marching on May Day with thousands of other people in the streets of Dublin, one of the questions that was posed to me was how could it be that International Workers’ Day is not celebrated in the U.S. I am still struggling to come up with a convincing explanation, as may be evident from this essay, but Gore Vidal was not off the mark when he said, “we are the United States of Amnesia.”

Nonetheless, the U.S. labor movement has not yet been defeated and is surely not dead. In spite of the bloody suppression and the constant intimidation over many decades, the U.S. labor movement has made its presence felt on numerous historic occasions, from the Battle of Cripple Creek in 1894 and the 1892 Homestead Strike in Pennsylvania to being behind the historic 1963 march on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, and continues doing so down to this day. Scores of victories for the working class were achieved last year—and all against prevailing odds. Moreover, in 2023, labor strikes in the U.S. jumped to a 23-year high and some of the largest labor disputes in the history of the U.S. were also recorded last year.

So, while May Day may have been formally obliterated by the powers that be from U.S. public awareness, the labor movement is still alive and kicking. Even a small victory is still a victory, though time will tell of the historic significance of each step forward. Indeed, it is highly unlikely that the unionists, socialists, and anarchists that made Chicago in 1886 the center of the national movement for the eight-hour workday had foreseen what the impact of their actions would be in the struggle of the international labor movement for democracy, better wages, safer working conditions, and freedom of speech. All these social rights have been amplified over time, though much remains to be accomplished and the struggle continues.

But this is all the more reason why we must not forget—and indeed celebrate every year with marches and protests—May 1st.

May 1st is International Workers’ Day and was established as such in celebration of the struggle for the introduction of the eight-hour workday and in memory of Chicago’s Haymarket Affair, which took place in 1886. May 1st is celebrated in over 160 countries with large-scale marches and protests as workers across the globe continue to fight for better working conditions, fair wages, and other labor rights. International Workers’ Day, however, is not celebrated in the U.S. and has in fact been practically erased from historical memory. But this shouldn’t be surprising since U.S. capitalism operates on the basis of a brutal economy where maximization of profit takes priority over everything else, including the environment and even human lives.

Indeed, the U.S. has a notorious record when it comes to worker rights. The country has the most violent and bloody history of labor relations in the advanced industrialized world, according to labor historians. Subsequently, unionization has always faced an uphill battle as corporations are allowed to engage in widespread union-busting practices through manipulation or violation of federal labor law. The recent activities of Amazon and Starbucks speak volumes of the anti-union mentality that pervades most U.S. corporations. Accordingly, unionization in the U.S. has been on decline for decades even though the majority of Americans see this development as a bad thing.

The backlash against unionization and worker rights in general in the U.S. also takes place against the backdrop of an insidious ideological framework in which it has been regarded as a self-evident truth that individuals are responsible for their own fate and that government should not interfere with the free market out of concern for social and economic inequalities.

While May Day may have been formally obliterated by the powers that be from U.S. public awareness, the labor movement is still alive and kicking.

Social Darwinism first appeared in U.S. political and social thought in the mid-1860s, as historian Richard Hofstadter showed in his brilliant work Social Darwinism in American Thought, 1860-1915, but it would be a gross mistake to think that it ever went away. The conservative counterrevolution launched by Ronald Reagan in the early 1980s and refined by Bill Clinton in the early 1990s aimed at bringing back the loathsome idea that the government should not interfere in the “survival of the fittest” by helping the weak and the poor. Progressive economic ideas have been on the whole an anathema to the U.S. political establishment and violence against labor militancy has always been the norm for almost all of the country’s political history.

Long before the movement for an eight-hour workday in the U.S., which can be largely attributed to the influx of European immigrants mainly from Italy and Germany, radicalism had set foot across a number of post-colonial states. Rhode Island, often referred to as the Rogue Island, had one of the most radical economic policies on revolutionary debt, which was wildly popular with farmers and common folks in general, and experimented with the idea of radical democracy. At approximately the same time, Shays’ rebellion in Massachusetts was also about money, debts, poverty, and democracy. Naturally, the elite in both states pulled out all stops to put an end to radicalism, and the pattern of suppressing popular demands has somehow survived in U.S. politics across time.

The pattern of suppressing social and political movements from below continued well into modern times. The Red Scare, climaxed in the late 1910s on account of the Russian revolution and the rise of labor strikes and then renewed with the anti-communist campaign of the 1940s, played a crucial role in the establishment’s fervent dedication to crushing radicalism in the U.S. and putting an end to challenges against capitalism.

In light of this, it is nothing short of a shame that May Day has been all but forgotten in U.S. political culture even though the day traces its origins to the fight of American laborers for a shorter workday.

Last year, after marching on May Day with thousands of other people in the streets of Dublin, one of the questions that was posed to me was how could it be that International Workers’ Day is not celebrated in the U.S. I am still struggling to come up with a convincing explanation, as may be evident from this essay, but Gore Vidal was not off the mark when he said, “we are the United States of Amnesia.”

Nonetheless, the U.S. labor movement has not yet been defeated and is surely not dead. In spite of the bloody suppression and the constant intimidation over many decades, the U.S. labor movement has made its presence felt on numerous historic occasions, from the Battle of Cripple Creek in 1894 and the 1892 Homestead Strike in Pennsylvania to being behind the historic 1963 march on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, and continues doing so down to this day. Scores of victories for the working class were achieved last year—and all against prevailing odds. Moreover, in 2023, labor strikes in the U.S. jumped to a 23-year high and some of the largest labor disputes in the history of the U.S. were also recorded last year.

So, while May Day may have been formally obliterated by the powers that be from U.S. public awareness, the labor movement is still alive and kicking. Even a small victory is still a victory, though time will tell of the historic significance of each step forward. Indeed, it is highly unlikely that the unionists, socialists, and anarchists that made Chicago in 1886 the center of the national movement for the eight-hour workday had foreseen what the impact of their actions would be in the struggle of the international labor movement for democracy, better wages, safer working conditions, and freedom of speech. All these social rights have been amplified over time, though much remains to be accomplished and the struggle continues.

But this is all the more reason why we must not forget—and indeed celebrate every year with marches and protests—May 1st.