SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

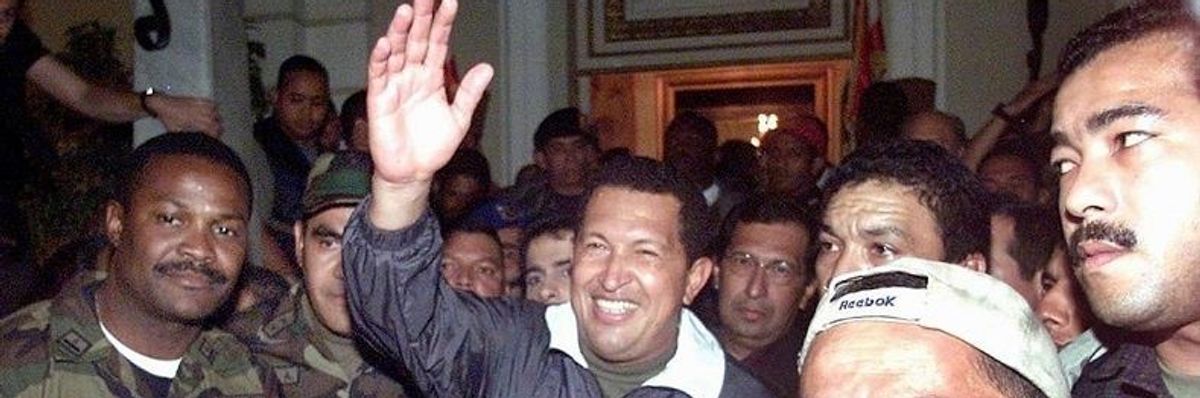

Hugo Chavez being returned to power on April13, 2002 after a right-wing coup briefly overthrew him.

The Monroe Doctrine became the ideological basis for US hegemony in the region, justifying the violation of the rights of nations of self-determination, as was the case for Venezuela in 2002 and since then.

On April 11, 2002, there was an attempted coup against President Hugo Chavez's democratically elected government in Venezuela. Chavez had prioritized programs to improve living conditions for those who were previously unrepresented, and established an independent foreign policy in favor of the nation's interests.

Chavez’s stance conflicted with the Monroe Doctrine of 1823, which laid the groundwork for the use of U.S. military force and other forms of intervention to oppose any government, be it foreign or regional, that jeopardized U.S. interests. The Monroe Doctrine became the ideological basis for US hegemony in the region, justifying the violation of the rights of nations of self-determination, as was the case for Venezuela in 2002 and since then.

With Washington's backing, Venezuela's pro-Washington elite, high-ranking military officials, leaders of the traditional labor organizations, the Catholic Church hierarchy, and the nation's chamber of commerce had embarked on ousting a popular government. The Chávez administration had redefined the rules of democracy by drafting a new Constitution, one that was voted on by the people, and that allowed for greater popular participation. The Chavez government was also reasserting its sovereignty over its vast oil wealth by ending the process of privatization of PDVSA, the state oil company. In September 2000, It organized a summit meeting in Caracas of OPEC oil-producing countries to stabilize prices at higher levels to increase the country’s main source of income.

Washington’s main opposition to Chávez's foreign policy came when he met with OPEC leaders considered to be U.S. adversaries, including the governments of Libya, Iraq and Iran in preparation for the 2000 OPEC summit. He met again with Saddam Hussein and Muhammar Ghaddafi the following year, and spoke out against the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan as a reaction to 9/11, saying "You can't combat terror with more terror."

An intelligence brief dated April 6, 2002 — a mere five days before the coup plot would be carried out — explicitly states that a coup was set to take place.

Under previous Venezuelan governments, neoliberal reforms had increased poverty and the police and military had used violent repression, but the U.S. still perceived Venezuela as a flourishing democracy. Nevertheless, upon Chavez's ascension, the fundamental premise of respecting an elected leader's mandate was swiftly ignored by the United States. A State Department cable leaked right before the coup revealed the dissident military factions’ intentions to detain and overthrow Chavez, exhibiting advanced knowledge and direct involvement with the conspiracy.

On April 10, a day before the coup, U.S. Ambassador Charles Shapiro spoke to the press after meeting the Mayor of Caracas and when asked if the U.S. supported President Chavez, his reply was: “We support democracy and the constitutional framework” and he advised U.S. citizens in Venezuela to “be careful”. The Caracas Mayor, by his side, said: “If he doesn’t rule like a democrat, Chavez will leave office sooner than later.”

What came after was a wave of violence and repression that led to the arrest of Chavez, the killing of 19 people and injuring of over hundred, and a business leader swearing himself in as President, followed by a visit from Ambassador Shapiro. All according to regular Monroe Doctrine protocol, thus far.

Yet the one factor not taken into consideration: the will of the Venezuelan people.

On April 13th, the people of Venezuela made history and made a dent on the Monroe Doctrine’s record. Community leaders and organizers, despite facing police repression and a corporate media blackout, took the streets to demand that Chavez was brought back to office. Military officers and troops, loyal to the Venezuelan Constitution that the people had given themselves, rose up against commanding officers and demanded that Chavez be reinstated as the legitimate President. This joint civilian and military popular rebellion to save Venezuelan democracy made history and overturned the Monroe Doctrine formula that had successfully overthrown other independent Latin American leaders in the past, such as Jacobo Arbenz, Salvador Allende, Joao Goulart, Juan Bosch and Jean-Bertrand Aristide.

The question we must ask on an anniversary like this is why the United States continues to insist on a 200-year-old doctrine that has its back turned to the aspirations of the peoples of Latin America and the Caribbean? Why does the U.S. government continue to promote violence, human rights violations, and undemocratic governance that we would not tolerate on our own soil? Why do we continue to make people suffer in places like Venezuela by sanctioning the entire country for standing up for their self-determination? Wouldn’t we, as a people, expect solidarity and respect for standing up for our own democratic ideals?

In the end, the Monroe Doctrine is condemned to failure because people’s determination to be free will always prevail. Why not turn, instead, to a policy of mutual cooperation, of respect for Latin American and Caribbean internal affairs? Why not convince rather than coerce, collaborate rather than take advantage? Why do we still not understand that the instability, violence, and exploitation we promote in our region backfires and leads to the migration challenges we face today in our own country?

In Venezuela now, there’s a popular saying that refers to the day of the 2002 coup and the day–two days later–that Chavez was reinstated: Every 11th has its 13th. It is a significant sign of the new Latin America and Caribbean that has emerged in the 21st Century, a region that wants to bury 200-year-old interventionism. For every Monroe Doctrine intervention, there will be an April 13th rebellion for sovereignty and dignity.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

On April 11, 2002, there was an attempted coup against President Hugo Chavez's democratically elected government in Venezuela. Chavez had prioritized programs to improve living conditions for those who were previously unrepresented, and established an independent foreign policy in favor of the nation's interests.

Chavez’s stance conflicted with the Monroe Doctrine of 1823, which laid the groundwork for the use of U.S. military force and other forms of intervention to oppose any government, be it foreign or regional, that jeopardized U.S. interests. The Monroe Doctrine became the ideological basis for US hegemony in the region, justifying the violation of the rights of nations of self-determination, as was the case for Venezuela in 2002 and since then.

With Washington's backing, Venezuela's pro-Washington elite, high-ranking military officials, leaders of the traditional labor organizations, the Catholic Church hierarchy, and the nation's chamber of commerce had embarked on ousting a popular government. The Chávez administration had redefined the rules of democracy by drafting a new Constitution, one that was voted on by the people, and that allowed for greater popular participation. The Chavez government was also reasserting its sovereignty over its vast oil wealth by ending the process of privatization of PDVSA, the state oil company. In September 2000, It organized a summit meeting in Caracas of OPEC oil-producing countries to stabilize prices at higher levels to increase the country’s main source of income.

Washington’s main opposition to Chávez's foreign policy came when he met with OPEC leaders considered to be U.S. adversaries, including the governments of Libya, Iraq and Iran in preparation for the 2000 OPEC summit. He met again with Saddam Hussein and Muhammar Ghaddafi the following year, and spoke out against the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan as a reaction to 9/11, saying "You can't combat terror with more terror."

An intelligence brief dated April 6, 2002 — a mere five days before the coup plot would be carried out — explicitly states that a coup was set to take place.

Under previous Venezuelan governments, neoliberal reforms had increased poverty and the police and military had used violent repression, but the U.S. still perceived Venezuela as a flourishing democracy. Nevertheless, upon Chavez's ascension, the fundamental premise of respecting an elected leader's mandate was swiftly ignored by the United States. A State Department cable leaked right before the coup revealed the dissident military factions’ intentions to detain and overthrow Chavez, exhibiting advanced knowledge and direct involvement with the conspiracy.

On April 10, a day before the coup, U.S. Ambassador Charles Shapiro spoke to the press after meeting the Mayor of Caracas and when asked if the U.S. supported President Chavez, his reply was: “We support democracy and the constitutional framework” and he advised U.S. citizens in Venezuela to “be careful”. The Caracas Mayor, by his side, said: “If he doesn’t rule like a democrat, Chavez will leave office sooner than later.”

What came after was a wave of violence and repression that led to the arrest of Chavez, the killing of 19 people and injuring of over hundred, and a business leader swearing himself in as President, followed by a visit from Ambassador Shapiro. All according to regular Monroe Doctrine protocol, thus far.

Yet the one factor not taken into consideration: the will of the Venezuelan people.

On April 13th, the people of Venezuela made history and made a dent on the Monroe Doctrine’s record. Community leaders and organizers, despite facing police repression and a corporate media blackout, took the streets to demand that Chavez was brought back to office. Military officers and troops, loyal to the Venezuelan Constitution that the people had given themselves, rose up against commanding officers and demanded that Chavez be reinstated as the legitimate President. This joint civilian and military popular rebellion to save Venezuelan democracy made history and overturned the Monroe Doctrine formula that had successfully overthrown other independent Latin American leaders in the past, such as Jacobo Arbenz, Salvador Allende, Joao Goulart, Juan Bosch and Jean-Bertrand Aristide.

The question we must ask on an anniversary like this is why the United States continues to insist on a 200-year-old doctrine that has its back turned to the aspirations of the peoples of Latin America and the Caribbean? Why does the U.S. government continue to promote violence, human rights violations, and undemocratic governance that we would not tolerate on our own soil? Why do we continue to make people suffer in places like Venezuela by sanctioning the entire country for standing up for their self-determination? Wouldn’t we, as a people, expect solidarity and respect for standing up for our own democratic ideals?

In the end, the Monroe Doctrine is condemned to failure because people’s determination to be free will always prevail. Why not turn, instead, to a policy of mutual cooperation, of respect for Latin American and Caribbean internal affairs? Why not convince rather than coerce, collaborate rather than take advantage? Why do we still not understand that the instability, violence, and exploitation we promote in our region backfires and leads to the migration challenges we face today in our own country?

In Venezuela now, there’s a popular saying that refers to the day of the 2002 coup and the day–two days later–that Chavez was reinstated: Every 11th has its 13th. It is a significant sign of the new Latin America and Caribbean that has emerged in the 21st Century, a region that wants to bury 200-year-old interventionism. For every Monroe Doctrine intervention, there will be an April 13th rebellion for sovereignty and dignity.

On April 11, 2002, there was an attempted coup against President Hugo Chavez's democratically elected government in Venezuela. Chavez had prioritized programs to improve living conditions for those who were previously unrepresented, and established an independent foreign policy in favor of the nation's interests.

Chavez’s stance conflicted with the Monroe Doctrine of 1823, which laid the groundwork for the use of U.S. military force and other forms of intervention to oppose any government, be it foreign or regional, that jeopardized U.S. interests. The Monroe Doctrine became the ideological basis for US hegemony in the region, justifying the violation of the rights of nations of self-determination, as was the case for Venezuela in 2002 and since then.

With Washington's backing, Venezuela's pro-Washington elite, high-ranking military officials, leaders of the traditional labor organizations, the Catholic Church hierarchy, and the nation's chamber of commerce had embarked on ousting a popular government. The Chávez administration had redefined the rules of democracy by drafting a new Constitution, one that was voted on by the people, and that allowed for greater popular participation. The Chavez government was also reasserting its sovereignty over its vast oil wealth by ending the process of privatization of PDVSA, the state oil company. In September 2000, It organized a summit meeting in Caracas of OPEC oil-producing countries to stabilize prices at higher levels to increase the country’s main source of income.

Washington’s main opposition to Chávez's foreign policy came when he met with OPEC leaders considered to be U.S. adversaries, including the governments of Libya, Iraq and Iran in preparation for the 2000 OPEC summit. He met again with Saddam Hussein and Muhammar Ghaddafi the following year, and spoke out against the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan as a reaction to 9/11, saying "You can't combat terror with more terror."

An intelligence brief dated April 6, 2002 — a mere five days before the coup plot would be carried out — explicitly states that a coup was set to take place.

Under previous Venezuelan governments, neoliberal reforms had increased poverty and the police and military had used violent repression, but the U.S. still perceived Venezuela as a flourishing democracy. Nevertheless, upon Chavez's ascension, the fundamental premise of respecting an elected leader's mandate was swiftly ignored by the United States. A State Department cable leaked right before the coup revealed the dissident military factions’ intentions to detain and overthrow Chavez, exhibiting advanced knowledge and direct involvement with the conspiracy.

On April 10, a day before the coup, U.S. Ambassador Charles Shapiro spoke to the press after meeting the Mayor of Caracas and when asked if the U.S. supported President Chavez, his reply was: “We support democracy and the constitutional framework” and he advised U.S. citizens in Venezuela to “be careful”. The Caracas Mayor, by his side, said: “If he doesn’t rule like a democrat, Chavez will leave office sooner than later.”

What came after was a wave of violence and repression that led to the arrest of Chavez, the killing of 19 people and injuring of over hundred, and a business leader swearing himself in as President, followed by a visit from Ambassador Shapiro. All according to regular Monroe Doctrine protocol, thus far.

Yet the one factor not taken into consideration: the will of the Venezuelan people.

On April 13th, the people of Venezuela made history and made a dent on the Monroe Doctrine’s record. Community leaders and organizers, despite facing police repression and a corporate media blackout, took the streets to demand that Chavez was brought back to office. Military officers and troops, loyal to the Venezuelan Constitution that the people had given themselves, rose up against commanding officers and demanded that Chavez be reinstated as the legitimate President. This joint civilian and military popular rebellion to save Venezuelan democracy made history and overturned the Monroe Doctrine formula that had successfully overthrown other independent Latin American leaders in the past, such as Jacobo Arbenz, Salvador Allende, Joao Goulart, Juan Bosch and Jean-Bertrand Aristide.

The question we must ask on an anniversary like this is why the United States continues to insist on a 200-year-old doctrine that has its back turned to the aspirations of the peoples of Latin America and the Caribbean? Why does the U.S. government continue to promote violence, human rights violations, and undemocratic governance that we would not tolerate on our own soil? Why do we continue to make people suffer in places like Venezuela by sanctioning the entire country for standing up for their self-determination? Wouldn’t we, as a people, expect solidarity and respect for standing up for our own democratic ideals?

In the end, the Monroe Doctrine is condemned to failure because people’s determination to be free will always prevail. Why not turn, instead, to a policy of mutual cooperation, of respect for Latin American and Caribbean internal affairs? Why not convince rather than coerce, collaborate rather than take advantage? Why do we still not understand that the instability, violence, and exploitation we promote in our region backfires and leads to the migration challenges we face today in our own country?

In Venezuela now, there’s a popular saying that refers to the day of the 2002 coup and the day–two days later–that Chavez was reinstated: Every 11th has its 13th. It is a significant sign of the new Latin America and Caribbean that has emerged in the 21st Century, a region that wants to bury 200-year-old interventionism. For every Monroe Doctrine intervention, there will be an April 13th rebellion for sovereignty and dignity.