SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

Investments of taxpayers’ money into dodgy deals, profiteering and exploitation, health scandals and human rights abuses —all with little or no accountability. This includes private hospitals imprisoning patients and retaining deceased relatives until bills are paid.

Patients living in poverty in the Global South are being bankrupted by private healthcare corporations backed by multi-million-dollar investments from development finance institutions (DFIs) run by the UK, French, German and other rich country governments.

DFIs like the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation (IFC) and the European Investment Bank (EIB) invest public funds via the private sector to help foster economic development in the Global South and tackle poverty.

However, today, Oxfam publishes two investigations on DFI funding into private hospital chains and other for-profit healthcare corporations operating in low- and middle-income countries and finds cases of them:

“For decades, rich countries have been wedded to a theory that public funds can underwrite the private sector in order to help low- and middle-income countries develop their healthcare sectors,” said Oxfam International’s Health Policy Lead Anna Marriott. “This has proved to be an evidence-free, rich country bankers’ guide to global healthcare —a free-for-all of private greed over public good— where the big winners are the super-rich investors and owners of healthcare corporations, and the losers being the masses facing rising poverty, sickness, discrimination and human rights abuses.”

Oxfam investigated investments by European DFIs into the booming private healthcare sectors of India, Kenya, Nigeria, Uganda and other Global South countries. It finds:

“Half the world’s population can’t get essential healthcare. Every second, sixty people are plunged into poverty by medical bills. Donor countries and development banks have long promised that they can drive down healthcare costs for people living in poverty by investing taxpayers’ money into the private sector. Instead, costs are rocketing up and causing harm,” Marriott said.

In India, where the private healthcare sector is now worth $236 billion and rising rapidly, the IFC has directly invested over half a billion dollars into some of the country’s largest corporate hospital chains, with more made indirectly via private equity, owned by some of the richest billionaires in India. Oxfam found:

The reports cite profit margins of up to 1,737 percent on drugs, consumables and diagnostics in four big hospital complexes in the Delhi-National Capital Region.

The Maputo Private Hospital in Mozambique, backed by the IFC during the pandemic, reportedly charged COVID-19 patients a $6,000 deposit for oxygen and $10,000 for a ventilator. Similarly, in Uganda, the Nakasero Hospital reportedly charged $1,900 per day for a COVID-19 bed in intensive care, while the TMR Hospital charged $116,000 for one patient who died from the virus. Nakasero Hospital is funded by France, the EU and the IFC while TMR Hospital is supported by the UK and France.

The Sírio-Libanês Hospital in Brazil, which has DFI investments from both Germany’s DEG and France’s Proparco, treats primarily a rich elite including Latin American celebrities and presidents. It boasts 500 security cameras, 250 electronic access controllers, 250 proximity sensors, 100 guards, and doctors who are trained to deal with the paparazzi.

While the number of mothers dying in pregnancy and childbirth is rising around the world, Oxfam found that DFI funded hospitals are far out of reach for those most needing life-saving healthcare. The average cost of an uncomplicated childbirth in these private hospitals is more than a year’s income for an average earner in the bottom 40 percent of the population, while the cost of a caesarean birth is more than two years’ income.

In Nigeria, nine in ten of the poorest women give birth with no midwife or skilled birth attendant. Oxfam tracked development funds from the EIB, Germany, France and the IFC to the high-end private Lagoon Hospitals in Lagos, where the most basic maternity package costs more than nine years’ income for the poorest 10 percent of Nigerians.

Spent wisely, aid and other forms of government spending are essential in order to save lives and drive development. Ethiopia successfully used aid to achieve most of the health-related Millenium Development Goals by 2015, including the reduction of maternal deaths by more than 70 percent. In lower-income countries doing the most to stop women dying in childbirth, 90 percent of their healthcare comes from the public sector. COVID-19 has demonstrated how health security is dependent on delivering healthcare for all goals everywhere as soon as possible.

“It is more urgent than ever that governments stop this dangerous diversion of public funds to private healthcare and instead deliver on aid and other public funding promises in order to strengthen public healthcare systems that can deliver for everybody. Global South governments should also step up and be more assertive in directing foreign public investments into better health outcomes for their people,” Marriott said.

Oxfam is calling for a stop to all future direct and indirect DFI funding to private healthcare and an urgent, independent investigation into all current and historical investments.Oxfam International is a global movement of people who are fighting inequality to end poverty and injustice. We are working across regions in about 70 countries, with thousands of partners, and allies, supporting communities to build better lives for themselves, grow resilience and protect lives and livelihoods also in times of crisis.

In some cases, the administration has kept immigrants locked up even after a judge has ordered their release, according to an investigation by Reuters.

Judges across the country have ruled more than 4,400 times since the start of October that US Immigration and Customs Enforcement has illegally detained immigrants, according to a Reuters investigation published Saturday.

As President Donald Trump carries out his unprecedented "mass deportation" crusade, the number of people in ICE custody ballooned to 68,000 this month, up 75% from when he took office.

Midway through 2025, the administration had begun pushing for a daily quota of 3,000 arrests per day, with the goal of reaching 1 million per year. This has led to the targeting of mostly people with no criminal records rather than the "worst of the worst," as the administration often claims.

Reuters' reporting suggests chasing this number has also resulted in a staggering number of arrests that judges have later found to be illegal.

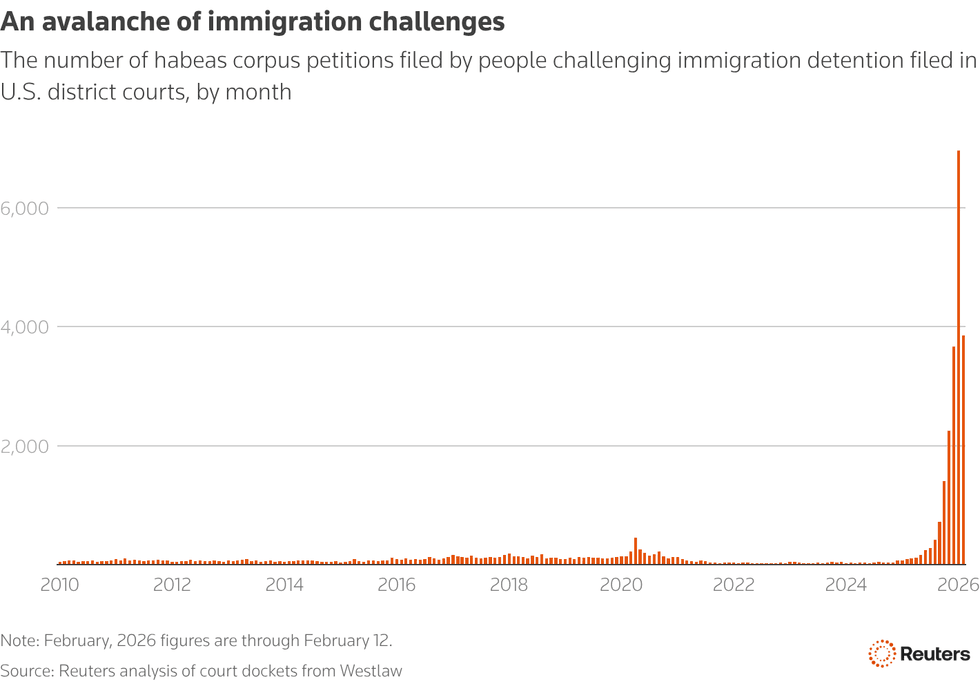

Since the beginning of Trump's term, immigrants have filed more than 20,200 habeas corpus petitions, claiming they were held indefinitely without trial in violation of the Constitution.

In at least 4,421 cases, more than 400 federal judges have ruled that their detentions were illegal.

Last month, more than 6,000 habeas petitions were filed. Prior to the second Trump administration, no other month dating back to 2010 had seen even 500.

In part due to the sheer volume of legal challenges, the Trump administration has often failed to comply with court rulings, leaving people locked up even after judges ordered them to be released.

Reuters' new report is the most comprehensive examination to date of the administration's routine violation of the law with respect to immigration enforcement. But the extent to which federal immigration agencies have violated the law under Trump is hardly new information.

In a ruling last month, Chief Judge Patrick J. Schiltz of the US District Court in Minnesota—a conservative jurist appointed by former President George W. Bush—provided a list of nearly 100 court orders ICE had violated just that month while deployed as part of Trump's Operation Metro Surge.

The report of ICE's systemic violation of the law comes as the agency faces heightened scrutiny on Capitol Hill, with leaders of the agency called to testify and Democrats attempting to hold up funding in order to force reforms to ICE's conduct, which resulted in a partial shutdown beginning Saturday.

Following the release of Reuters' report, Rep. Ted Lieu (D-Calif.) directed a pointed question over social media to Kristi Noem, the secretary of the Department of Homeland Security, which oversees ICE.

"Why do your out-of-control agents keep violating federal law?" he said. "I look forward to seeing you testify under oath at the House Judiciary Committee in early March."

"Aggies do what is necessary for our rights, for our survival, and for our people,” said one student organizer at North Carolina A&T State University, the largest historically Black college in the nation.

As early voting began for the state primaries, North Carolina college students found themselves walking more than a mile to cast their ballots after the Republican-controlled State Board of Elections closed polling places on their campuses.

The board, which shifted to a 3-2 GOP majority, voted last month to close a polling site at Western Carolina University and to reject the creation of polling sites at two other colleges—the University of North Carolina at Greensboro (UNC Greensboro), and the North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University (NC A&T), the largest historically Black college in the nation. Each of these schools had polling places available on campus during the 2024 election.

The decision, which came just weeks before early voting was scheduled to begin, left many of the 40,000 students who attend these schools more than a mile away from the nearest polling place.

It was the latest of many efforts by North Carolina Republicans to restrict voting ahead of the 2026 midterms: They also cut polling place hours in dozens of counties and eliminated early voting on Sundays in some, which dealt a blow to "Souls to the Polls" efforts led by Black churches.

A lawsuit filed late last month by a group of students at the three schools said, “as a result, students who do not have access to private transportation must now walk that distance—which includes walking along a highway that lacks any pedestrian infrastructure—to exercise their right to vote.

The students argued that this violates their access to the ballot and to same-day registration, which is only available during the early voting period.

Last week, a federal judge rejected their demand to open the three polling centers. Jay Pavey, a Republican member of the Jackson County elections board, who voted to close the WCU polling site, dismissed fears that it would limit voting.

“If you really want to vote, you'll find a way to go one mile,” Pavey said.

Despite the hurdles, hundreds of students in the critical battleground state remained determined to cast a ballot as early voting opened.

On Friday, a video posted by the Smoky Mountain News showed dozens of students marching in a line from WCU "to their new polling place," at the Jackson County Recreation Center, "1.7 miles down a busy highway with no sidewalks."

The university and on-campus groups also organized shuttles to and from the polling place.

A similar scene was documented at NC A&T, where about 60 students marched to their nearest polling place at a courthouse more than 1.3 miles away.

The students described their march as a protest against the state's decision, which they viewed as an attempt to limit their power at the ballot box.

The campus is no stranger to standing up against injustice. February 1 marked the 66th anniversary of when four Black NC A&T students launched one of the most pivotal protests of the civil rights movement, sitting down at a segregated Woolworth's lunch counter in downtown Greensboro—an act that sparked a wave of nonviolent civil disobedience across the South.

"Aggies do what is necessary for our rights, for our survival, and for our people,” Jae'lah Monet, one of the student organizers of the march, told Spectrum News 1.

Monet said she and other students will do what is necessary to get students to the polls safely and to demonstrate to the state board the importance of having a polling place on campus. She said several similar events will take place throughout the early voting period.

"We will be there all day, and we will all get a chance to vote," Monet said.

"We need massive reforms in DHS with real accountability before we send another dime their way," said Rep. Pramila Jayapal.

The US Department of Homeland Security partially shut down on Saturday at midnight after Congress failed to reach an agreement to reform its immigration agencies, which have faced mounting scrutiny after the killings of multiple US citizens and rampant civil rights violations.

A shutdown was virtually assured when lawmakers left town for a recess on Thursday without a deal that included Democrats' key demands to rein in Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and Customs and Border Protection (CBP).

Sixty votes are needed to pass any deal through the Senate, meaning seven Democrats would need to join every Republican to break the stalemate.

Democrats have demanded that agents around the nation wear body cameras, carry identification, and stop hiding their identities with masks. They said agents must adhere to the Constitution by obtaining judicial warrants before entering private property and ending the use of racial profiling.

Senate Republicans on Thursday attempted to pass another short-term funding measure that would keep the agency running while negotiations play out. But without adopting any of the Democrats' reforms, Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) said his party would "not support a blank check for chaos."

The bill was voted down 47-52, with only one Democrat, the ICE-defending Sen. John Fetterman (D-Pa.) voting in support.

The lapse in funding comes amid a whirlwind of scandals surrounding DHS, most notably the fatal shootings in Minneapolis of two US citizens, Alex Pretti and Renee Good, last month. DHS officials, including Secretary Kristi Noem, immediately leapt to justify the killings in contradiction to video evidence, which smeared the victims as "domestic terrorists" before any investigation took place.

Earlier this week, unsealed body camera footage showed definitively that the agency also lied about the shooting of 30-year-old US citizen Marimar Martinez in Chicago in October.

On Friday, it was reported that two ICE agents are under investigation for making false statements about the events leading up to yet another shooting of a Venezuelan national, Julio Cesar Sosa-Celis, in Minnesota last month.

In a rare acknowledgement of wrongdoing by his agency, ICE's acting director, Todd Lyons, said on Friday that the agents appear “to have made untruthful statements” about what led to his shooting.

An explosive Wall Street Journal report also recently put Noem further under the microscope, revealing an alleged romantic relationship with top Trump adviser Corey Lewandowski, who insiders said has been put in charge of the agency's contracting despite being only a temporary "special government employee" and has reportedly doled out contracts in an "opaque and arbitrary manner."

The DHS shutdown will not affect funding for immigration agencies, since both ICE and CBP received more than $70 billion from Congress last summer as part of the GOP's massive tax and spending bill.

Their activities are expected to continue normally during the shutdown. But other functions of the agency may see delays and funding lapses.

While most Transportation Security Administration (TSA) employees are considered essential and expected to stay on the job, more may begin to stay home if the shutdown drags on and they miss paychecks. Some Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) funding for states' disaster recovery may also be delayed as a result of the shutdown, and employees may be furloughed, slowing the process.

Congress is expected to reconvene on February 23 after a weeklong recess, but may return earlier if a deal is reached during the break.

Democrats have appeared largely united on holding out unless significant reforms are achieved, though party leaders—Schumer and House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries (D-NY) have faced a crisis of confidence within their own caucus, as they've appeared willing to taper back some demands—including masking requirements—in order to find a compromise.

As the clock inched toward midnight on Friday, Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-Wash.), the chair emerita of the Congressional Progressive Caucus, emphasized the existential stakes of the fight ahead.

"If the government shuts down, it will be because Republicans refuse to hold DHS and their deplorable actions accountable," she said. "The reality is if we start to erode the rights of some, we start to erode the rights of all—and I will not stand for it. We need massive reforms in DHS with real accountability before we send another dime their way."