San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge construction. (Photo: Fred Sharples CC BY 2.0)

Revealed: Americans Care More About Social Needs Than Deficits

A recent poll from the Democracy Collaborative and YouGov reveals that most Americans are ready to spend more for social needs, even if it raises the deficit

The debate around modern monetary theory ("MMT") is picking up steam - with its partisans pushing the model further into the public sphere than one might expect, and the old guard of establishment economics, together with some more interesting critical voices, pushing back.

The questions at stake can make the average person's head spin: can a government with sovereign control over its currency create money at will to meet social needs, or would this create out of control inflationary spirals? Does tax income precede government spending, or does spending create the money that's then taxed back to tweak the distribution of incomes and rein in inflation?

To most Americans, this is all probably a bit opaque and abstract - the inner workings of our money supply and its deep connections to the banking sector are, after all, as Bill Greider memorably put it, "the secrets of the temple." But when we look at the core issue, we find that more Americans than not agree with the basic political judgement that MMT tries to justify theoretically - namely, that deficits shouldn't matter if social needs are not being met.

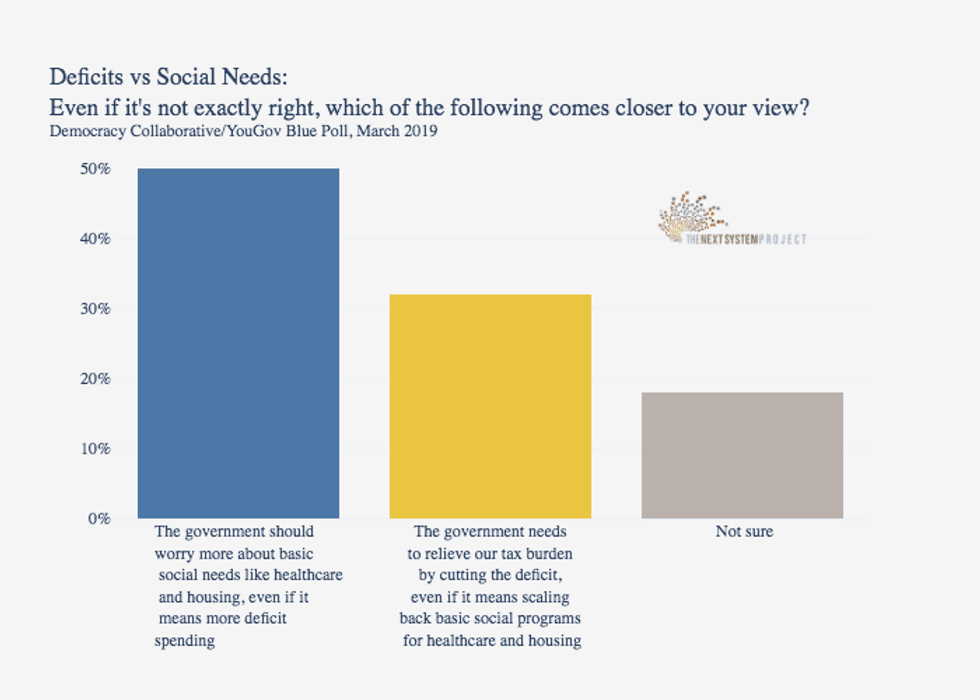

At the Democracy Collaborative, a poll we commissioned with YouGov shows this preference clearly. 50% of respondents thought "the government should worry more about basic social needs like healthcare and housing, even if it means more deficit spending" compared to just 32% who felt that "the government needs to relieve our tax burden by cutting the deficit, even if it means scaling back basic social programs for healthcare and housing." So while most Americans probably don't have an opinion on the intricacies of heterodox monetary theory, by a significant margin, more of them agree with MMT's political conclusions about spending.

The debate around modern monetary theory ("MMT") is picking up steam - with its partisans pushing the model further into the public sphere than one might expect, and the old guard of establishment economics, together with some more interesting critical voices, pushing back.

The questions at stake can make the average person's head spin: can a government with sovereign control over its currency create money at will to meet social needs, or would this create out of control inflationary spirals? Does tax income precede government spending, or does spending create the money that's then taxed back to tweak the distribution of incomes and rein in inflation?

To most Americans, this is all probably a bit opaque and abstract - the inner workings of our money supply and its deep connections to the banking sector are, after all, as Bill Greider memorably put it, "the secrets of the temple." But when we look at the core issue, we find that more Americans than not agree with the basic political judgement that MMT tries to justify theoretically - namely, that deficits shouldn't matter if social needs are not being met.

At the Democracy Collaborative, a poll we commissioned with YouGov shows this preference clearly. 50% of respondents thought "the government should worry more about basic social needs like healthcare and housing, even if it means more deficit spending" compared to just 32% who felt that "the government needs to relieve our tax burden by cutting the deficit, even if it means scaling back basic social programs for healthcare and housing." So while most Americans probably don't have an opinion on the intricacies of heterodox monetary theory, by a significant margin, more of them agree with MMT's political conclusions about spending.

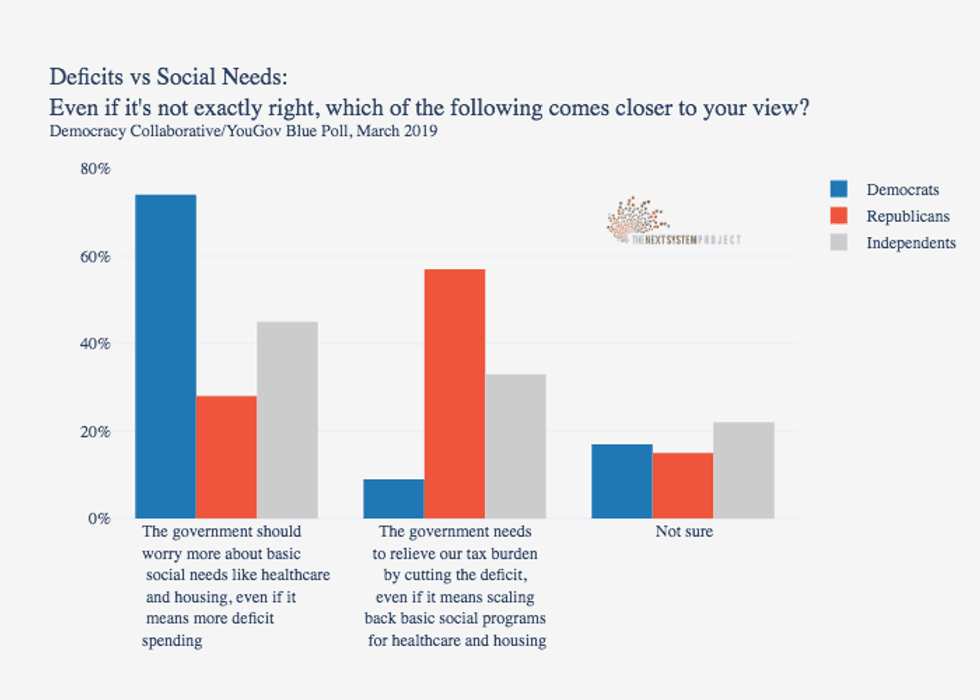

Of course, with trigger words like "tax burden" and "deficits" included, we did see a sharp partisan tilt in our results. Still, it's encouraging to see that nearly 1 in 3 Republicans don't think deficits matter more than social spending. And with 74% percent of Democrats ready to spend more to meet basic needs even if it increases the deficit, the kind of austerity-lite Paygo triangulation advanced by Speaker Pelosi seems utterly incomprehensible.

The point is to recognize that whether or not we can decide in favor of or against MMT is somewhat academic. There are a wide range of important technical issues to be worked out around tax, interest, and full employment policies - but when we're operating in a context where actually existing financialized capitalism regularly features negative interest rates, trillions of dollars of central bank asset purchases, and seemingly unlimited tax cuts for the rich, letting ourselves be boxed in by technocratic assumptions about what's feasible according to economic theory seems uncalled for.

We should identify the priorities we want, and then build the monetary and fiscal mechanisms we need to get there - rather than cowering before the supposedly terrible and unknowable forces of money and the economy. The lesson of the last crash should not be that the market is an unpredictable and capricious god, it should be that when you design a system to incentivize untrammeled financialization you get exactly what you asked for. So let's start instead with what the majority of people want the economy to do for them, and then design and build with those goals in mind.

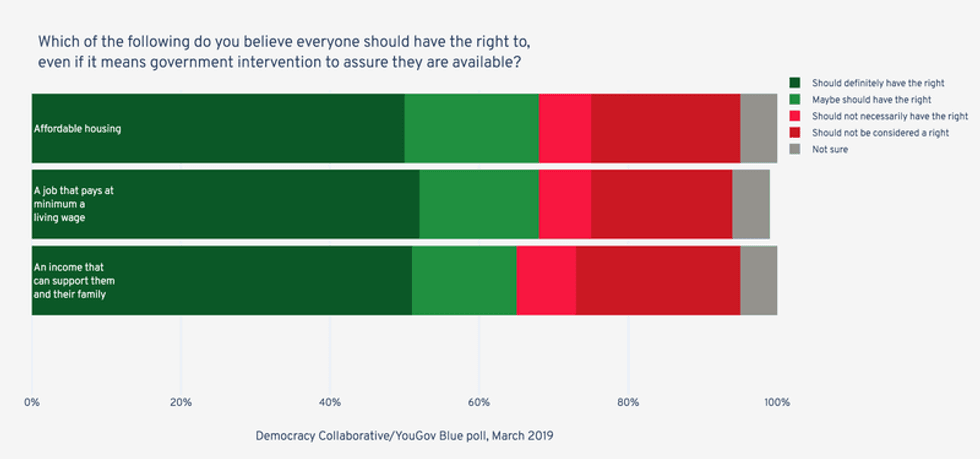

As our polling showed, these goals are simple but powerful. Fundamentally, most people agree that the economy should be delivering better outcomes, and believe that government intervention is a good way to guarantee that these outcomes happen. We asked whether people had a right to "an income that can support them and their family," "a job that pays at minimum a living wage," and "affordable housing" - for all three of these basic demands, respondents who thought people "should" or "maybe should" have this right was between 65% and 68% of those surveyed, compared to just 26%-30% of respondents who felt that people "should not" or "should not necessarily" enjoy those rights.

Austerity's insistent nag "but how will we pay for it?" should not be the starting point of our political imagination. Rather, we should start from an economic agenda designed to deliver better outcomes on key goals in the most direct way possible, and then creatively work out "how will we pay for it" as a matter of technical due diligence - with the understanding that deficits are only an absolute constraint for those intent on austerity at all costs. The answers we arrive at may or may not draw from MMT's proposed insights, although they should be honest and realistic in either case. When the policymakers and central bankers of the 1% are willing to break every rule in the economics textbook to protect and expand an unequal status quo, we shouldn't be afraid to demand basic economic human rights first, and leave it to the economists to invent a way to pay for it.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

The debate around modern monetary theory ("MMT") is picking up steam - with its partisans pushing the model further into the public sphere than one might expect, and the old guard of establishment economics, together with some more interesting critical voices, pushing back.

The questions at stake can make the average person's head spin: can a government with sovereign control over its currency create money at will to meet social needs, or would this create out of control inflationary spirals? Does tax income precede government spending, or does spending create the money that's then taxed back to tweak the distribution of incomes and rein in inflation?

To most Americans, this is all probably a bit opaque and abstract - the inner workings of our money supply and its deep connections to the banking sector are, after all, as Bill Greider memorably put it, "the secrets of the temple." But when we look at the core issue, we find that more Americans than not agree with the basic political judgement that MMT tries to justify theoretically - namely, that deficits shouldn't matter if social needs are not being met.

At the Democracy Collaborative, a poll we commissioned with YouGov shows this preference clearly. 50% of respondents thought "the government should worry more about basic social needs like healthcare and housing, even if it means more deficit spending" compared to just 32% who felt that "the government needs to relieve our tax burden by cutting the deficit, even if it means scaling back basic social programs for healthcare and housing." So while most Americans probably don't have an opinion on the intricacies of heterodox monetary theory, by a significant margin, more of them agree with MMT's political conclusions about spending.

The debate around modern monetary theory ("MMT") is picking up steam - with its partisans pushing the model further into the public sphere than one might expect, and the old guard of establishment economics, together with some more interesting critical voices, pushing back.

The questions at stake can make the average person's head spin: can a government with sovereign control over its currency create money at will to meet social needs, or would this create out of control inflationary spirals? Does tax income precede government spending, or does spending create the money that's then taxed back to tweak the distribution of incomes and rein in inflation?

To most Americans, this is all probably a bit opaque and abstract - the inner workings of our money supply and its deep connections to the banking sector are, after all, as Bill Greider memorably put it, "the secrets of the temple." But when we look at the core issue, we find that more Americans than not agree with the basic political judgement that MMT tries to justify theoretically - namely, that deficits shouldn't matter if social needs are not being met.

At the Democracy Collaborative, a poll we commissioned with YouGov shows this preference clearly. 50% of respondents thought "the government should worry more about basic social needs like healthcare and housing, even if it means more deficit spending" compared to just 32% who felt that "the government needs to relieve our tax burden by cutting the deficit, even if it means scaling back basic social programs for healthcare and housing." So while most Americans probably don't have an opinion on the intricacies of heterodox monetary theory, by a significant margin, more of them agree with MMT's political conclusions about spending.

Of course, with trigger words like "tax burden" and "deficits" included, we did see a sharp partisan tilt in our results. Still, it's encouraging to see that nearly 1 in 3 Republicans don't think deficits matter more than social spending. And with 74% percent of Democrats ready to spend more to meet basic needs even if it increases the deficit, the kind of austerity-lite Paygo triangulation advanced by Speaker Pelosi seems utterly incomprehensible.

The point is to recognize that whether or not we can decide in favor of or against MMT is somewhat academic. There are a wide range of important technical issues to be worked out around tax, interest, and full employment policies - but when we're operating in a context where actually existing financialized capitalism regularly features negative interest rates, trillions of dollars of central bank asset purchases, and seemingly unlimited tax cuts for the rich, letting ourselves be boxed in by technocratic assumptions about what's feasible according to economic theory seems uncalled for.

We should identify the priorities we want, and then build the monetary and fiscal mechanisms we need to get there - rather than cowering before the supposedly terrible and unknowable forces of money and the economy. The lesson of the last crash should not be that the market is an unpredictable and capricious god, it should be that when you design a system to incentivize untrammeled financialization you get exactly what you asked for. So let's start instead with what the majority of people want the economy to do for them, and then design and build with those goals in mind.

As our polling showed, these goals are simple but powerful. Fundamentally, most people agree that the economy should be delivering better outcomes, and believe that government intervention is a good way to guarantee that these outcomes happen. We asked whether people had a right to "an income that can support them and their family," "a job that pays at minimum a living wage," and "affordable housing" - for all three of these basic demands, respondents who thought people "should" or "maybe should" have this right was between 65% and 68% of those surveyed, compared to just 26%-30% of respondents who felt that people "should not" or "should not necessarily" enjoy those rights.

Austerity's insistent nag "but how will we pay for it?" should not be the starting point of our political imagination. Rather, we should start from an economic agenda designed to deliver better outcomes on key goals in the most direct way possible, and then creatively work out "how will we pay for it" as a matter of technical due diligence - with the understanding that deficits are only an absolute constraint for those intent on austerity at all costs. The answers we arrive at may or may not draw from MMT's proposed insights, although they should be honest and realistic in either case. When the policymakers and central bankers of the 1% are willing to break every rule in the economics textbook to protect and expand an unequal status quo, we shouldn't be afraid to demand basic economic human rights first, and leave it to the economists to invent a way to pay for it.

The debate around modern monetary theory ("MMT") is picking up steam - with its partisans pushing the model further into the public sphere than one might expect, and the old guard of establishment economics, together with some more interesting critical voices, pushing back.

The questions at stake can make the average person's head spin: can a government with sovereign control over its currency create money at will to meet social needs, or would this create out of control inflationary spirals? Does tax income precede government spending, or does spending create the money that's then taxed back to tweak the distribution of incomes and rein in inflation?

To most Americans, this is all probably a bit opaque and abstract - the inner workings of our money supply and its deep connections to the banking sector are, after all, as Bill Greider memorably put it, "the secrets of the temple." But when we look at the core issue, we find that more Americans than not agree with the basic political judgement that MMT tries to justify theoretically - namely, that deficits shouldn't matter if social needs are not being met.

At the Democracy Collaborative, a poll we commissioned with YouGov shows this preference clearly. 50% of respondents thought "the government should worry more about basic social needs like healthcare and housing, even if it means more deficit spending" compared to just 32% who felt that "the government needs to relieve our tax burden by cutting the deficit, even if it means scaling back basic social programs for healthcare and housing." So while most Americans probably don't have an opinion on the intricacies of heterodox monetary theory, by a significant margin, more of them agree with MMT's political conclusions about spending.

The debate around modern monetary theory ("MMT") is picking up steam - with its partisans pushing the model further into the public sphere than one might expect, and the old guard of establishment economics, together with some more interesting critical voices, pushing back.

The questions at stake can make the average person's head spin: can a government with sovereign control over its currency create money at will to meet social needs, or would this create out of control inflationary spirals? Does tax income precede government spending, or does spending create the money that's then taxed back to tweak the distribution of incomes and rein in inflation?

To most Americans, this is all probably a bit opaque and abstract - the inner workings of our money supply and its deep connections to the banking sector are, after all, as Bill Greider memorably put it, "the secrets of the temple." But when we look at the core issue, we find that more Americans than not agree with the basic political judgement that MMT tries to justify theoretically - namely, that deficits shouldn't matter if social needs are not being met.

At the Democracy Collaborative, a poll we commissioned with YouGov shows this preference clearly. 50% of respondents thought "the government should worry more about basic social needs like healthcare and housing, even if it means more deficit spending" compared to just 32% who felt that "the government needs to relieve our tax burden by cutting the deficit, even if it means scaling back basic social programs for healthcare and housing." So while most Americans probably don't have an opinion on the intricacies of heterodox monetary theory, by a significant margin, more of them agree with MMT's political conclusions about spending.

Of course, with trigger words like "tax burden" and "deficits" included, we did see a sharp partisan tilt in our results. Still, it's encouraging to see that nearly 1 in 3 Republicans don't think deficits matter more than social spending. And with 74% percent of Democrats ready to spend more to meet basic needs even if it increases the deficit, the kind of austerity-lite Paygo triangulation advanced by Speaker Pelosi seems utterly incomprehensible.

The point is to recognize that whether or not we can decide in favor of or against MMT is somewhat academic. There are a wide range of important technical issues to be worked out around tax, interest, and full employment policies - but when we're operating in a context where actually existing financialized capitalism regularly features negative interest rates, trillions of dollars of central bank asset purchases, and seemingly unlimited tax cuts for the rich, letting ourselves be boxed in by technocratic assumptions about what's feasible according to economic theory seems uncalled for.

We should identify the priorities we want, and then build the monetary and fiscal mechanisms we need to get there - rather than cowering before the supposedly terrible and unknowable forces of money and the economy. The lesson of the last crash should not be that the market is an unpredictable and capricious god, it should be that when you design a system to incentivize untrammeled financialization you get exactly what you asked for. So let's start instead with what the majority of people want the economy to do for them, and then design and build with those goals in mind.

As our polling showed, these goals are simple but powerful. Fundamentally, most people agree that the economy should be delivering better outcomes, and believe that government intervention is a good way to guarantee that these outcomes happen. We asked whether people had a right to "an income that can support them and their family," "a job that pays at minimum a living wage," and "affordable housing" - for all three of these basic demands, respondents who thought people "should" or "maybe should" have this right was between 65% and 68% of those surveyed, compared to just 26%-30% of respondents who felt that people "should not" or "should not necessarily" enjoy those rights.

Austerity's insistent nag "but how will we pay for it?" should not be the starting point of our political imagination. Rather, we should start from an economic agenda designed to deliver better outcomes on key goals in the most direct way possible, and then creatively work out "how will we pay for it" as a matter of technical due diligence - with the understanding that deficits are only an absolute constraint for those intent on austerity at all costs. The answers we arrive at may or may not draw from MMT's proposed insights, although they should be honest and realistic in either case. When the policymakers and central bankers of the 1% are willing to break every rule in the economics textbook to protect and expand an unequal status quo, we shouldn't be afraid to demand basic economic human rights first, and leave it to the economists to invent a way to pay for it.