The Alternative to Fervent Nationalism Isn't Corporate Liberalism--It's Social Democracy

In his 1946 essay reviewing former Trotskyist-turned-reactionary James Burnham's book The Managerial Revolution, George Orwell made several observations that resonate just as powerfully today as they did when they were first published.

In his 1946 essay reviewing former Trotskyist-turned-reactionary James Burnham's book The Managerial Revolution, George Orwell made several observations that resonate just as powerfully today as they did when they were first published.

"The real question," he wrote, "is not whether the people who wipe their boots on us during the next fifty years are to be called managers, bureaucrats, or politicians: the question is whether capitalism, now obviously doomed, is to give way to oligarchy or to true democracy."

Orwell recognized what many today fail to perceive: That free market capitalism is, in the words of Karl Polanyi, a "stark Utopia," a system that does not exist, and one that would not survive for long if it ever came into existence.

But for Orwell, the question was not how (or whether) the crises of capitalism that rocked both Europe and the United States in the 20th century would be solved -- the question was: what would take the place of an economic order that was clearly on its way out?

Read today, his prediction of the world to come emanates prescience.

"For quite fifty years past the general drift has almost certainly been towards oligarchy," Orwell argued. "The ever-increasing concentration of industrial and financial power; the diminishing importance of the individual capitalist or shareholder, and the growth of the new 'managerial' class of scientists, technicians, and bureaucrats; the weakness of the proletariat against the centralised state; the increasing helplessness of small countries against big ones; the decay of representative institutions and the appearance of one-party regimes based on police terrorism, faked plebiscites, etc.: all these things seem to point in the same direction."

This year has in some ways marked the peak of these trends -- trends that are currently being exploited (as they always have been) by both genuine nationalists and political opportunists looking to capitalize on the destabilizing effects of the international economic order.

Globally, the concentration of income at the very top is obscene: As a widely cited Oxfam report notes, 62 people own the same amount of wealth as half of the world's population. The report also found that as the wealth of the global elite continues to soar, "the wealth of the poorest half of the world's population has fallen by a trillion dollars since 2010, a drop of 38 percent."

And such trends have not just inflicted the poorest. The middle class in the United States, for instance, has been steadily eroding over the past several decades in the face of slow growth and stagnant wages. Meanwhile, top CEOs have seen their incomes rise by over 900 percent.

People are reacting. From the rise of Donald Trump and right-wing nationalists throughout Europe to the United Kingdom's vote to leave the European Union, people are using the influence they still have to express their contempt for a system that has failed them and their families.

Some of the discontent is undoubtedly motivated by racial animus and anti-immigrant sentiment, both of which have been preyed upon by charlatans across the globe. But it has also been motivated by class antagonism, by a general feeling that economic and political elites are making out like bandits while the public is forced to scramble for an ever-dwindling piece of the pie.

Responses to these developments by apologists for elites and by elites themselves have been varied, but all have had a common core: The United States and Europe are, contrary to popular perception, suffering from too much democracy.

The leash restraining the people, the argument goes, has been excessively loosened, and, consequently, the "ignorant masses" have wreaked havoc. More or less, the proposed solution has been to tighten the leash.

In a recent piece for Foreign Policy, James Traub calls on "elites to rise up against the ignorant masses." They must put the people in their place with facts and reason, with the decent sense that "the mob" lacks by definition.

Traub's was perhaps the most explicit and aggressive call to action, and, as he notes in his latest work for the same outlet, he has reaped a storm of criticism.

With a hint of regret, Traub insists that his point was misunderstood. The notion, Traub explains, that "people who take issue with the forces of globalization, whether from the left or the right, should defer to elites" is "repellent."

This latest piece was, when it was first published, provocatively titled "Liberalism Isn't Working." The title has since been altered, but the core point remains: Europe and the United States, Traub argues, are experiencing "the breakdown of the liberal order."

In Traub's view, irrationality is prevailing over reason -- noticeable in, for instance, popular disdain for "experts" -- and illiberal democracy is taking the place of what was previously liberal democracy. Intolerance is replacing tolerance. Those who "can't stand the way the world is going and want to return to a mythical golden age where women and Mexicans and refugees and gays and atheists didn't disturb the public with their demands" are defeating those who favor diversity and free thought.

It is heartening to see Traub walk back his elitist war cry, and he is correct that liberalism in its current form -- that is to say, corporate liberalism, or neoliberalism -- has failed to muster an adequate response to the various crises facing global society.

But this is not because liberals have no desire to do so; it is because their ideological system is utterly bankrupt, divorced from the needs of the masses and subservient to the needs of organized wealth.

Traub notes, perhaps correctly, that President Obama's "remote, cerebral manner has...whetted the public's appetite for a snake-oil salesman like Trump."

More than his "manner," though, Obama's ideological bent -- largely shared by Hillary Clinton and other corporate Democrats -- has left a vacuum into which phony populists like Trump have emerged.

And this is what Traub fails to consider: The alternative to Trumpism is not more smug, corporate liberalism that manages the decline and tempers the expectations of the masses; it is, rather, an ambitious social agenda that utilizes mass politics to create an economic and political order that is responsive to the material needs of the population.

Contrary to the urgent warnings that we are suffering from an excess of democracy, the United States and Europe have for too long been gripped by a democratic deficit.

"If we want to avert the sense of powerlessness among voters that fuels demagogy," writes Michael Lind, "the answer is not less democracy in America, but more."

Traub and others like him have succeeded in putting forward critiques of the movements responding to the discontent of the masses, but they have failed to criticize the economic order whose failures have sparked this discontent. As a result, they have failed to offer a compelling alternative to the surging nationalism they profess to fear.

And as Luke Savage notes in a recent piece for Jacobin, the self-styled experts have often done much worse than that.

He points to the fact that "beyond a few largely anecdotal comments about globalization, Traub offers no real analysis of the causes driving the polarization he so detests. In familiar tones, he conflates the populist right and the populist left, and characterizes anti-establishment sentiment as the product of sheer, mindless democratic stupidity."

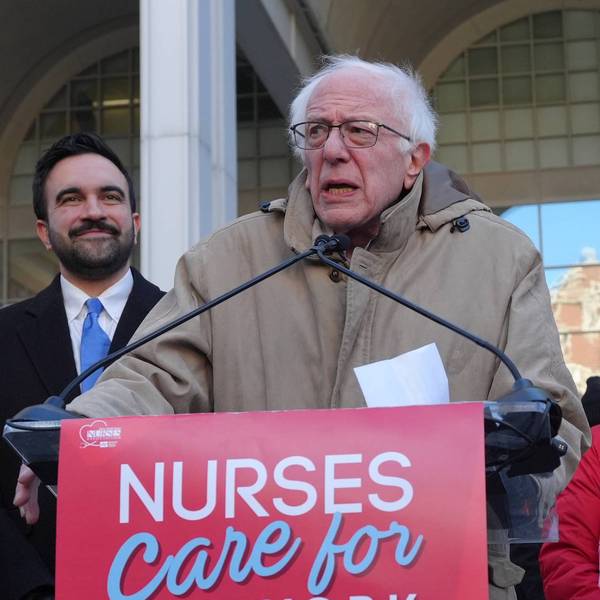

In effect, the expert class has -- predictably -- erased from view the agendas of figures like Bernie Sanders, figures who represent an alternative to both fervent nationalism and neoliberalism.

And far from putting forward radical and unworkable proposals, the ideas on which the Sanders campaign has been based have far-reaching appeal.

Ultimately, Savage concludes, "the real political schism of our time" is "not one between 'the sane and the mindlessly angry,' but between democrats and technocratic elites."

It is, for instance, elite opinion, not public opinion, that stands in the way of the implementation of single-payer healthcare.

Most of the public, furthermore, believes that "major donors sway Congress more than constituents," but it is elites -- including self-styled progressives -- who stand in the way of campaign finance reform.

The so-called "ignorant masses" understand that "there is too much power concentrated in the hands of a few big companies," and that "the government doesn't do enough for older people, poor people or children." But it is elites whose entrenched interests undercut any attempt to remedy these trends.

There is, in short, an appetite for social democracy in the United States, but it is elites -- economic and political -- who stand in the way and insist that such an appetite is the result of excessive imagination.

Conservatives -- including Trump -- continue to fight unabashedly for the needs of corporate America, while neoliberals like President Obama and Hillary Clinton insist that progressive initiatives must be curbed in the interest of "getting things done."

But such a commitment to "pragmatism" is, in reality, a lack of commitment to the systemic change necessary in the midst of unprecedented inequality, horrific levels of child poverty, an intolerably high rate of infant mortality, neglected communities, and other crises that require radical action.

Interestingly, in his essay James Traub cites George Orwell as one of the "great exponents" of liberalism and anti-totalitarianism.

But he fails to mention what Orwell, himself, wrote about his own political motivations, which he expressed in his 1946 essay "Why I Write."

"Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936," Orwell notes, "has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic Socialism, as I understand it."

Needless to say, Orwell's vision was not a hierarchical one that placed technocratic elites and self-proclaimed experts at the helm; it was one that warned of totalitarianism of all forms and proposed a more egalitarian alternative.

By ignoring this -- deliberately or otherwise -- and by establishing a status quo of austerity, intolerable inequality, environmental degradation, and endless war, elites have fostered the reaction they are now attempting to beat back.

But their proposed alternative is, effectively, more of the same. That, as much of the world's population recognizes, is not enough.

"It's not about the EU," notes Mark Blyth in an assessment of the European economy that applies just as well to the United States. "It's about the elites. It's about the 1%. It's about the fact that your parties that were meant to serve your interests have sold you down the river."

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

In his 1946 essay reviewing former Trotskyist-turned-reactionary James Burnham's book The Managerial Revolution, George Orwell made several observations that resonate just as powerfully today as they did when they were first published.

"The real question," he wrote, "is not whether the people who wipe their boots on us during the next fifty years are to be called managers, bureaucrats, or politicians: the question is whether capitalism, now obviously doomed, is to give way to oligarchy or to true democracy."

Orwell recognized what many today fail to perceive: That free market capitalism is, in the words of Karl Polanyi, a "stark Utopia," a system that does not exist, and one that would not survive for long if it ever came into existence.

But for Orwell, the question was not how (or whether) the crises of capitalism that rocked both Europe and the United States in the 20th century would be solved -- the question was: what would take the place of an economic order that was clearly on its way out?

Read today, his prediction of the world to come emanates prescience.

"For quite fifty years past the general drift has almost certainly been towards oligarchy," Orwell argued. "The ever-increasing concentration of industrial and financial power; the diminishing importance of the individual capitalist or shareholder, and the growth of the new 'managerial' class of scientists, technicians, and bureaucrats; the weakness of the proletariat against the centralised state; the increasing helplessness of small countries against big ones; the decay of representative institutions and the appearance of one-party regimes based on police terrorism, faked plebiscites, etc.: all these things seem to point in the same direction."

This year has in some ways marked the peak of these trends -- trends that are currently being exploited (as they always have been) by both genuine nationalists and political opportunists looking to capitalize on the destabilizing effects of the international economic order.

Globally, the concentration of income at the very top is obscene: As a widely cited Oxfam report notes, 62 people own the same amount of wealth as half of the world's population. The report also found that as the wealth of the global elite continues to soar, "the wealth of the poorest half of the world's population has fallen by a trillion dollars since 2010, a drop of 38 percent."

And such trends have not just inflicted the poorest. The middle class in the United States, for instance, has been steadily eroding over the past several decades in the face of slow growth and stagnant wages. Meanwhile, top CEOs have seen their incomes rise by over 900 percent.

People are reacting. From the rise of Donald Trump and right-wing nationalists throughout Europe to the United Kingdom's vote to leave the European Union, people are using the influence they still have to express their contempt for a system that has failed them and their families.

Some of the discontent is undoubtedly motivated by racial animus and anti-immigrant sentiment, both of which have been preyed upon by charlatans across the globe. But it has also been motivated by class antagonism, by a general feeling that economic and political elites are making out like bandits while the public is forced to scramble for an ever-dwindling piece of the pie.

Responses to these developments by apologists for elites and by elites themselves have been varied, but all have had a common core: The United States and Europe are, contrary to popular perception, suffering from too much democracy.

The leash restraining the people, the argument goes, has been excessively loosened, and, consequently, the "ignorant masses" have wreaked havoc. More or less, the proposed solution has been to tighten the leash.

In a recent piece for Foreign Policy, James Traub calls on "elites to rise up against the ignorant masses." They must put the people in their place with facts and reason, with the decent sense that "the mob" lacks by definition.

Traub's was perhaps the most explicit and aggressive call to action, and, as he notes in his latest work for the same outlet, he has reaped a storm of criticism.

With a hint of regret, Traub insists that his point was misunderstood. The notion, Traub explains, that "people who take issue with the forces of globalization, whether from the left or the right, should defer to elites" is "repellent."

This latest piece was, when it was first published, provocatively titled "Liberalism Isn't Working." The title has since been altered, but the core point remains: Europe and the United States, Traub argues, are experiencing "the breakdown of the liberal order."

In Traub's view, irrationality is prevailing over reason -- noticeable in, for instance, popular disdain for "experts" -- and illiberal democracy is taking the place of what was previously liberal democracy. Intolerance is replacing tolerance. Those who "can't stand the way the world is going and want to return to a mythical golden age where women and Mexicans and refugees and gays and atheists didn't disturb the public with their demands" are defeating those who favor diversity and free thought.

It is heartening to see Traub walk back his elitist war cry, and he is correct that liberalism in its current form -- that is to say, corporate liberalism, or neoliberalism -- has failed to muster an adequate response to the various crises facing global society.

But this is not because liberals have no desire to do so; it is because their ideological system is utterly bankrupt, divorced from the needs of the masses and subservient to the needs of organized wealth.

Traub notes, perhaps correctly, that President Obama's "remote, cerebral manner has...whetted the public's appetite for a snake-oil salesman like Trump."

More than his "manner," though, Obama's ideological bent -- largely shared by Hillary Clinton and other corporate Democrats -- has left a vacuum into which phony populists like Trump have emerged.

And this is what Traub fails to consider: The alternative to Trumpism is not more smug, corporate liberalism that manages the decline and tempers the expectations of the masses; it is, rather, an ambitious social agenda that utilizes mass politics to create an economic and political order that is responsive to the material needs of the population.

Contrary to the urgent warnings that we are suffering from an excess of democracy, the United States and Europe have for too long been gripped by a democratic deficit.

"If we want to avert the sense of powerlessness among voters that fuels demagogy," writes Michael Lind, "the answer is not less democracy in America, but more."

Traub and others like him have succeeded in putting forward critiques of the movements responding to the discontent of the masses, but they have failed to criticize the economic order whose failures have sparked this discontent. As a result, they have failed to offer a compelling alternative to the surging nationalism they profess to fear.

And as Luke Savage notes in a recent piece for Jacobin, the self-styled experts have often done much worse than that.

He points to the fact that "beyond a few largely anecdotal comments about globalization, Traub offers no real analysis of the causes driving the polarization he so detests. In familiar tones, he conflates the populist right and the populist left, and characterizes anti-establishment sentiment as the product of sheer, mindless democratic stupidity."

In effect, the expert class has -- predictably -- erased from view the agendas of figures like Bernie Sanders, figures who represent an alternative to both fervent nationalism and neoliberalism.

And far from putting forward radical and unworkable proposals, the ideas on which the Sanders campaign has been based have far-reaching appeal.

Ultimately, Savage concludes, "the real political schism of our time" is "not one between 'the sane and the mindlessly angry,' but between democrats and technocratic elites."

It is, for instance, elite opinion, not public opinion, that stands in the way of the implementation of single-payer healthcare.

Most of the public, furthermore, believes that "major donors sway Congress more than constituents," but it is elites -- including self-styled progressives -- who stand in the way of campaign finance reform.

The so-called "ignorant masses" understand that "there is too much power concentrated in the hands of a few big companies," and that "the government doesn't do enough for older people, poor people or children." But it is elites whose entrenched interests undercut any attempt to remedy these trends.

There is, in short, an appetite for social democracy in the United States, but it is elites -- economic and political -- who stand in the way and insist that such an appetite is the result of excessive imagination.

Conservatives -- including Trump -- continue to fight unabashedly for the needs of corporate America, while neoliberals like President Obama and Hillary Clinton insist that progressive initiatives must be curbed in the interest of "getting things done."

But such a commitment to "pragmatism" is, in reality, a lack of commitment to the systemic change necessary in the midst of unprecedented inequality, horrific levels of child poverty, an intolerably high rate of infant mortality, neglected communities, and other crises that require radical action.

Interestingly, in his essay James Traub cites George Orwell as one of the "great exponents" of liberalism and anti-totalitarianism.

But he fails to mention what Orwell, himself, wrote about his own political motivations, which he expressed in his 1946 essay "Why I Write."

"Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936," Orwell notes, "has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic Socialism, as I understand it."

Needless to say, Orwell's vision was not a hierarchical one that placed technocratic elites and self-proclaimed experts at the helm; it was one that warned of totalitarianism of all forms and proposed a more egalitarian alternative.

By ignoring this -- deliberately or otherwise -- and by establishing a status quo of austerity, intolerable inequality, environmental degradation, and endless war, elites have fostered the reaction they are now attempting to beat back.

But their proposed alternative is, effectively, more of the same. That, as much of the world's population recognizes, is not enough.

"It's not about the EU," notes Mark Blyth in an assessment of the European economy that applies just as well to the United States. "It's about the elites. It's about the 1%. It's about the fact that your parties that were meant to serve your interests have sold you down the river."

In his 1946 essay reviewing former Trotskyist-turned-reactionary James Burnham's book The Managerial Revolution, George Orwell made several observations that resonate just as powerfully today as they did when they were first published.

"The real question," he wrote, "is not whether the people who wipe their boots on us during the next fifty years are to be called managers, bureaucrats, or politicians: the question is whether capitalism, now obviously doomed, is to give way to oligarchy or to true democracy."

Orwell recognized what many today fail to perceive: That free market capitalism is, in the words of Karl Polanyi, a "stark Utopia," a system that does not exist, and one that would not survive for long if it ever came into existence.

But for Orwell, the question was not how (or whether) the crises of capitalism that rocked both Europe and the United States in the 20th century would be solved -- the question was: what would take the place of an economic order that was clearly on its way out?

Read today, his prediction of the world to come emanates prescience.

"For quite fifty years past the general drift has almost certainly been towards oligarchy," Orwell argued. "The ever-increasing concentration of industrial and financial power; the diminishing importance of the individual capitalist or shareholder, and the growth of the new 'managerial' class of scientists, technicians, and bureaucrats; the weakness of the proletariat against the centralised state; the increasing helplessness of small countries against big ones; the decay of representative institutions and the appearance of one-party regimes based on police terrorism, faked plebiscites, etc.: all these things seem to point in the same direction."

This year has in some ways marked the peak of these trends -- trends that are currently being exploited (as they always have been) by both genuine nationalists and political opportunists looking to capitalize on the destabilizing effects of the international economic order.

Globally, the concentration of income at the very top is obscene: As a widely cited Oxfam report notes, 62 people own the same amount of wealth as half of the world's population. The report also found that as the wealth of the global elite continues to soar, "the wealth of the poorest half of the world's population has fallen by a trillion dollars since 2010, a drop of 38 percent."

And such trends have not just inflicted the poorest. The middle class in the United States, for instance, has been steadily eroding over the past several decades in the face of slow growth and stagnant wages. Meanwhile, top CEOs have seen their incomes rise by over 900 percent.

People are reacting. From the rise of Donald Trump and right-wing nationalists throughout Europe to the United Kingdom's vote to leave the European Union, people are using the influence they still have to express their contempt for a system that has failed them and their families.

Some of the discontent is undoubtedly motivated by racial animus and anti-immigrant sentiment, both of which have been preyed upon by charlatans across the globe. But it has also been motivated by class antagonism, by a general feeling that economic and political elites are making out like bandits while the public is forced to scramble for an ever-dwindling piece of the pie.

Responses to these developments by apologists for elites and by elites themselves have been varied, but all have had a common core: The United States and Europe are, contrary to popular perception, suffering from too much democracy.

The leash restraining the people, the argument goes, has been excessively loosened, and, consequently, the "ignorant masses" have wreaked havoc. More or less, the proposed solution has been to tighten the leash.

In a recent piece for Foreign Policy, James Traub calls on "elites to rise up against the ignorant masses." They must put the people in their place with facts and reason, with the decent sense that "the mob" lacks by definition.

Traub's was perhaps the most explicit and aggressive call to action, and, as he notes in his latest work for the same outlet, he has reaped a storm of criticism.

With a hint of regret, Traub insists that his point was misunderstood. The notion, Traub explains, that "people who take issue with the forces of globalization, whether from the left or the right, should defer to elites" is "repellent."

This latest piece was, when it was first published, provocatively titled "Liberalism Isn't Working." The title has since been altered, but the core point remains: Europe and the United States, Traub argues, are experiencing "the breakdown of the liberal order."

In Traub's view, irrationality is prevailing over reason -- noticeable in, for instance, popular disdain for "experts" -- and illiberal democracy is taking the place of what was previously liberal democracy. Intolerance is replacing tolerance. Those who "can't stand the way the world is going and want to return to a mythical golden age where women and Mexicans and refugees and gays and atheists didn't disturb the public with their demands" are defeating those who favor diversity and free thought.

It is heartening to see Traub walk back his elitist war cry, and he is correct that liberalism in its current form -- that is to say, corporate liberalism, or neoliberalism -- has failed to muster an adequate response to the various crises facing global society.

But this is not because liberals have no desire to do so; it is because their ideological system is utterly bankrupt, divorced from the needs of the masses and subservient to the needs of organized wealth.

Traub notes, perhaps correctly, that President Obama's "remote, cerebral manner has...whetted the public's appetite for a snake-oil salesman like Trump."

More than his "manner," though, Obama's ideological bent -- largely shared by Hillary Clinton and other corporate Democrats -- has left a vacuum into which phony populists like Trump have emerged.

And this is what Traub fails to consider: The alternative to Trumpism is not more smug, corporate liberalism that manages the decline and tempers the expectations of the masses; it is, rather, an ambitious social agenda that utilizes mass politics to create an economic and political order that is responsive to the material needs of the population.

Contrary to the urgent warnings that we are suffering from an excess of democracy, the United States and Europe have for too long been gripped by a democratic deficit.

"If we want to avert the sense of powerlessness among voters that fuels demagogy," writes Michael Lind, "the answer is not less democracy in America, but more."

Traub and others like him have succeeded in putting forward critiques of the movements responding to the discontent of the masses, but they have failed to criticize the economic order whose failures have sparked this discontent. As a result, they have failed to offer a compelling alternative to the surging nationalism they profess to fear.

And as Luke Savage notes in a recent piece for Jacobin, the self-styled experts have often done much worse than that.

He points to the fact that "beyond a few largely anecdotal comments about globalization, Traub offers no real analysis of the causes driving the polarization he so detests. In familiar tones, he conflates the populist right and the populist left, and characterizes anti-establishment sentiment as the product of sheer, mindless democratic stupidity."

In effect, the expert class has -- predictably -- erased from view the agendas of figures like Bernie Sanders, figures who represent an alternative to both fervent nationalism and neoliberalism.

And far from putting forward radical and unworkable proposals, the ideas on which the Sanders campaign has been based have far-reaching appeal.

Ultimately, Savage concludes, "the real political schism of our time" is "not one between 'the sane and the mindlessly angry,' but between democrats and technocratic elites."

It is, for instance, elite opinion, not public opinion, that stands in the way of the implementation of single-payer healthcare.

Most of the public, furthermore, believes that "major donors sway Congress more than constituents," but it is elites -- including self-styled progressives -- who stand in the way of campaign finance reform.

The so-called "ignorant masses" understand that "there is too much power concentrated in the hands of a few big companies," and that "the government doesn't do enough for older people, poor people or children." But it is elites whose entrenched interests undercut any attempt to remedy these trends.

There is, in short, an appetite for social democracy in the United States, but it is elites -- economic and political -- who stand in the way and insist that such an appetite is the result of excessive imagination.

Conservatives -- including Trump -- continue to fight unabashedly for the needs of corporate America, while neoliberals like President Obama and Hillary Clinton insist that progressive initiatives must be curbed in the interest of "getting things done."

But such a commitment to "pragmatism" is, in reality, a lack of commitment to the systemic change necessary in the midst of unprecedented inequality, horrific levels of child poverty, an intolerably high rate of infant mortality, neglected communities, and other crises that require radical action.

Interestingly, in his essay James Traub cites George Orwell as one of the "great exponents" of liberalism and anti-totalitarianism.

But he fails to mention what Orwell, himself, wrote about his own political motivations, which he expressed in his 1946 essay "Why I Write."

"Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936," Orwell notes, "has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic Socialism, as I understand it."

Needless to say, Orwell's vision was not a hierarchical one that placed technocratic elites and self-proclaimed experts at the helm; it was one that warned of totalitarianism of all forms and proposed a more egalitarian alternative.

By ignoring this -- deliberately or otherwise -- and by establishing a status quo of austerity, intolerable inequality, environmental degradation, and endless war, elites have fostered the reaction they are now attempting to beat back.

But their proposed alternative is, effectively, more of the same. That, as much of the world's population recognizes, is not enough.

"It's not about the EU," notes Mark Blyth in an assessment of the European economy that applies just as well to the United States. "It's about the elites. It's about the 1%. It's about the fact that your parties that were meant to serve your interests have sold you down the river."