State-Level Single Payer a Good Step Toward Medicare for All

Will passage of a state-based program serve as an initial step towards a national program or derail the nationwide effort for a federal plan?

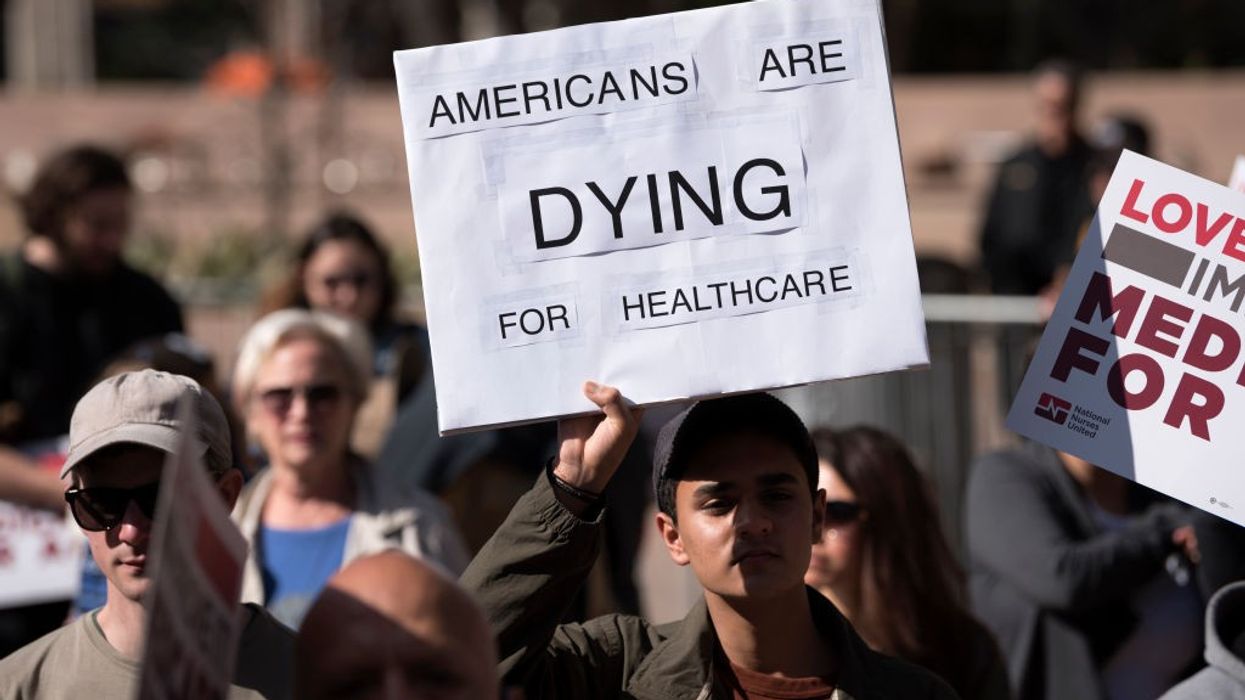

The consequences of President Donald Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) are already apparent. Millions have already lost health insurance. Millions more face soaring costs.

Nevertheless, fierce political opposition to a national Medicare for All legislation remains. The only possible path forward is to enact universal health care programs in those states where the electorate will be receptive. To facilitate this process, the State Based Universal Health Care Act (SBUHCA) has been introduced into both the United States Senate (S. 2286) and House (HR. 4406). This bill establishes minimal standards for state-based healthcare delivery programs and codifies the transfer of funds for healthcare services from Medicare, Medicaid, and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) to states with state-based programs.

Over the past 60 years, repeated attempts to improve the quality and availability of healthcare have had some success. In 1965, President Lyndon Johnson passed our first national healthcare legislation: Medicare for those age 65 and over and for younger adults with disabilities. Medicaid for indigent people. Most working- and middle-class Americans were excluded. Presumably working Americans would get health insurance via their workplace. Presidents Clinton and Obama, neither of whom pushed for passage of a universal program, were able to pass legislation providing incremental change. Clinton’s “Healthcare Act of 1997” and Obama’s “Affordable Care Act” of 2010 reduced the number of uninsured Americans. These bills, however, did not insure everyone or address segregation within the insurance system. They did not stem the rising cost of health care or reduce the number of underinsured persons with medical debt. They are responsible for the convoluted and cumbersome healthcare system we have today.

It is helpful to look back at the Social Security Amendment of 1965 that created the Medicare and Medicaid programs. In the days before the 1965 Civil Rights Act, Democrats usually enjoyed wide majorities in both the Senate and the House. There was however a confounder. Their majority included a block of Southern politicians whose principles were akin to those of their Civil War era Democratic Party predecessors. To gain their support, Johnson had to craft legislation that would somehow assure continued inequality between White and Black Americans. A true Medicare program was offered only to older retired Americans. That legislation required that hospital funding would be contingent upon hospital desegregation. In fact, hospital desegregation was achieved. Working age people however would be served by Medicaid, a program with means testing that provides care only to people at the poverty level. Details of the program are left to the discretion of the states. Most wage-earning, working-class people are thus excluded from the government program. Practical details of the program are left to the discretion of each state. The drawback became apparent during Covid when ten red states rejected the Medicaid supplements offered via the Affordable Care Act. Covid mortality in those states was greater than in those that participated in the Medicaid expansion.

Passage of a state-based program thus poses a conundrum: will passage of a state-based program serve as an initial step towards a national program? Or, with single-payer programs in place in progressive states, will the push for true national universal program be abandoned? The Medicaid experience bodes poorly for the success of a state-based plan. On the other hand, the history of the Canadian healthcare system shows that a state-based program may serve as a solid foundation for evolution to a nationwide plan. The Canadian program began in 1947 as a Saskatchewan-wide hospital insurance program for that province. Over the years, health programs were developed in other provinces such that in 1984, these coalesced into one: the Federal Canada Health Act.

With its New York Health Act (NYHA), New York State is now at the forefront of the movement toward state-based healthcare legislation. The notion that progressive legislation should originate in New York State has precedent. In the aftermath of the early 20th century Greenwich Village Triangle Shirtwaist Company fire, Frances Perkins, then a social worker and executive secretary of the newly formed Statewide Committee on Safety, was instrumental in crafting minimum wage, child labor and worker safety laws for the State. These State laws would later become the template for much of FDR’s New Deal legislation.

The NYHA would provide comprehensive coverage to all New York residents. The bill would establish a trust fund to hold money for patients and pay providers. Providers would bill the fund for services. Fees would be negotiated. Patients’ choices of physicians would not be limited by networks or prior authorizations. Nor would the bill dictate physicians’ methods of practice. All New Yorkers would pay a progressive graduated annual tax scaled according to income. Capital gains and stock transfers would be taxed as well. Additional funds would be available from Medicare, Medicaid, and CHIP. While these funds could be transferred to the states via a wraparound process, SBUHCA would codify this transfer of funds. Patients would make no further healthcare payments. No co-pays, deductions, payment at the point of service, or denials. No one would have medical debt. It is projected that 9 of 10 New Yorkers would pay less for medical care under the NYHA than they pay now.

New Yorkers can afford the NYHA. All other industrial nations provide better care to their citizens and at lower cost. New York can do the same. The cost of providing comprehensive care to include those services now not covered by Medicare, e.g., dental, visual and auditory along with long term care, is large. But eliminating the middlemen in the insurance, pharmaceutical and other provider industries would produce sizable savings. A recent Rand Corporation analysis assumed that the rates for physicians’ fees and other service providers would be greater than Medicare rates but less than that of more generous providers. The analysis concluded that the NYHA would reduce the overall cost of healthcare by 4%.

Where does the NYHA stand today? The process of advancing legislation from its drafting toits passage is arduous. Presently, the NYHA has a majority of co-sponsors in both chambers: 32 in the Senate; 78 in the Assembly. More public support for the bill is necessary, however, before legislators will advance the bill to the legislative chambers for a vote. Opposition from two major public service unions has also hindered efforts to bring the bill to a vote.

Passage of the NYHA would be a meaningful forward step toward adequate health insurance for all. We must continue the fight.