SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

With us was Hakim, a medical doctor who spent six years working as a public health specialist in the central highlands of Afghanistan and, prior to that, among refugees in Quetta, Pakistan. He helped us understand conditions that lead to food shortages and taught us about diseases, such as kwashiorkor and marasmus, which are caused by insufficient protein or general malnutrition.

We looked at UN figures about hunger in Afghanistan which show malnutrition rates rising by 50% or more compared with 2012. The malnutrition ward at Helmand Province's Bost Hospital has been admitting 200 children a month for severe, acute malnutrition -- four times more than in January 2012.

A recent New York Times article about the worsening hunger crisis described an encounter with a mother and child in an Afghan hospital: "In another bed is Fatima, less than a year old, who is so severely malnourished that her heart is failing, and the doctors expect that she will soon die unless her father is able to find money to take her to Kabul for surgery. The girl's face bears a perpetual look of utter terror, and she rarely stops crying."

Photos of Fatima and other children in the ward accompanied the article. In our room in Kabul, Hakim projected the photos on the wall. They were painful to see and so were the nods of comprehension from Afghans all too familiar with the agonies of poverty in a time of war.

As children grow, they need iodine to enable proper brain development. According to a UNICEF/GAIN report, "iodine deficiency is the most prevalent cause of brain damage worldwide. It is easily preventable, and through ongoing targeted interventions, can be eliminated." As recently as 2009 we learned that 70% of Afghan children faced an iodine deficiency.

Universal Salt Iodization (USI) is recognized as a simple, safe and cost-effective measure in addressing iodine deficiency. The World Bank reports that it costs $.05 per child, per year.

In 2012, the World Food Programme (WFP) and the Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN) announced a four-year project which aimed to reach nearly half of Afghanistan's population - 15 million Afghans - with fortified foods. Their strategy was to add vitamins and minerals such as iron, zinc, folic acid, Vitamin B-12 and Vitamin A to wheat flour, vegetable oil and ghee, and also to fortify salt with iodine. The project costs 6.4 million dollars.

The sums of money required to fund delivery of iodine and fortified foods to malnourished Afghan children should be compared, I believe, to the sums of money that the Pentagon's insatiable appetite for war-making has required of U.S. people.

The price tag for supplying iodized salt to one child for one year is 5 cents.

The cost of maintaining one U.S. soldier has recently risen to 2.1. million dollars per year. The amount of money spent to keep three U.S. soldiers in Afghanistan in 2014 could almost cover the cost of a four year program to deliver fortified foods to 15 million Afghan people.

Maj. Gen. Kurt J. Stein, who is overseeing the drawdown of U.S. troops from Afghanistan, has referred to the operation as "the largest retrograde mission in history." The mission will cost as much as $6 billion.

Over the past decade, spin doctors for U.S. military spending have suggested that Afghanistan needs the U.S. troop presence and U.S. non-military spending to protect the interests of women and children.

It's true that non-military aid to Afghanistan, sent by the U.S. since 2002, now approaches 100 billion dollars.

Several articles on Afghanistan's worsening hunger crisis, appearing in the Western press, prompt readers to ask how Afghanistan could be receiving vast sums of non-military aid and yet still struggle with severe acute malnourishment among children under age five.

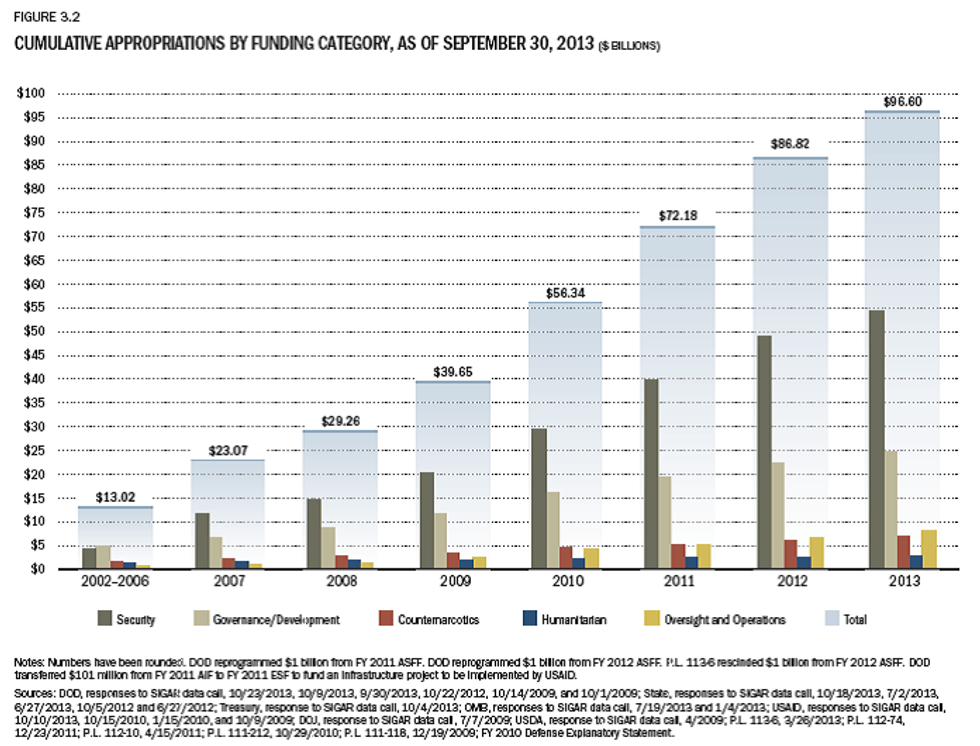

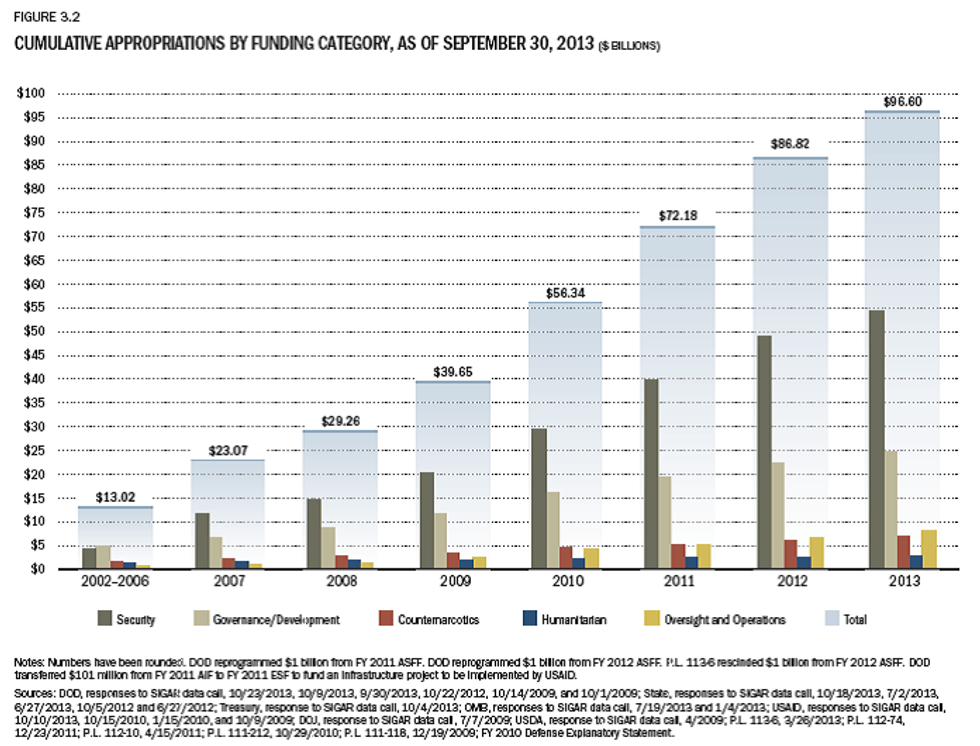

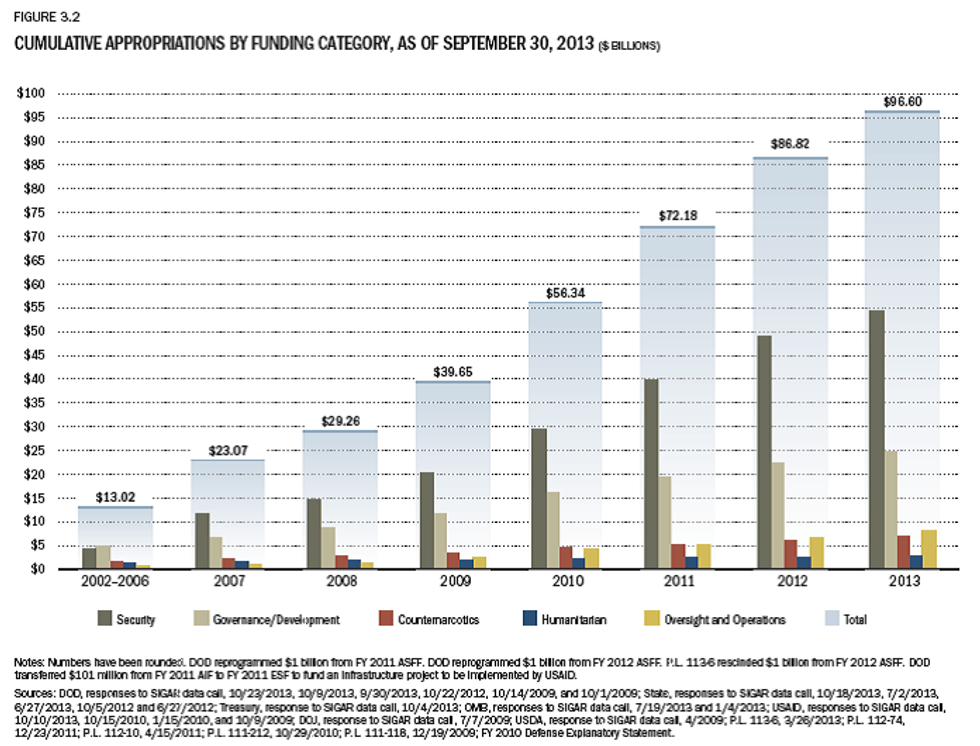

However, a 2013 quarterly report to Congress submitted by the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan shows that, of the nearly $100 billion spent on wartime reconstruction, 97 billion has been spent on counter-narcotics, security, "governance/development" and "oversight and operations." No more than $3 billion, a hundred dollars per Afghan person, were used for "humanitarian" projects - to help keep thirty million Afghans alive through twelve years of U.S. war and occupation.

Funds have been available for tanks, guns, bullets, helicopters, missiles, weaponized drones, drone surveillance, Joint Special Operations task forces, bases, airstrips, prisons, and truck delivered supplies for tens of thousands of troops. But funds are in short supply for children too weak to cry who are battling for their lives while wasting away.

A whole generation of Afghans and other people around the developing world see the true results of Westerners' self-righteous claim for the need to keep civilians "safe" through war. They see the terror, entirely justified, filling Fatima's eyes in her hospital bed.

In that room in Kabul, as my friends learned about the stark realities of hunger -- and among them, I know, were some who worry about hunger in their own families -- I could see a rejection both of panic and of revenge in the eyes of the people around me. Their steady thoughtfulness was an inspiration.

Panic and revenge among far more prosperous people in the U.S. helped to drive the U.S. into a war waged against one of the poorest countries in the world. Yet, my Afghan friends, who've borne the brunt of war, long to rise above vengeance and narrow self-interest.

They wish to pursue a peace that includes ending hunger.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

With us was Hakim, a medical doctor who spent six years working as a public health specialist in the central highlands of Afghanistan and, prior to that, among refugees in Quetta, Pakistan. He helped us understand conditions that lead to food shortages and taught us about diseases, such as kwashiorkor and marasmus, which are caused by insufficient protein or general malnutrition.

We looked at UN figures about hunger in Afghanistan which show malnutrition rates rising by 50% or more compared with 2012. The malnutrition ward at Helmand Province's Bost Hospital has been admitting 200 children a month for severe, acute malnutrition -- four times more than in January 2012.

A recent New York Times article about the worsening hunger crisis described an encounter with a mother and child in an Afghan hospital: "In another bed is Fatima, less than a year old, who is so severely malnourished that her heart is failing, and the doctors expect that she will soon die unless her father is able to find money to take her to Kabul for surgery. The girl's face bears a perpetual look of utter terror, and she rarely stops crying."

Photos of Fatima and other children in the ward accompanied the article. In our room in Kabul, Hakim projected the photos on the wall. They were painful to see and so were the nods of comprehension from Afghans all too familiar with the agonies of poverty in a time of war.

As children grow, they need iodine to enable proper brain development. According to a UNICEF/GAIN report, "iodine deficiency is the most prevalent cause of brain damage worldwide. It is easily preventable, and through ongoing targeted interventions, can be eliminated." As recently as 2009 we learned that 70% of Afghan children faced an iodine deficiency.

Universal Salt Iodization (USI) is recognized as a simple, safe and cost-effective measure in addressing iodine deficiency. The World Bank reports that it costs $.05 per child, per year.

In 2012, the World Food Programme (WFP) and the Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN) announced a four-year project which aimed to reach nearly half of Afghanistan's population - 15 million Afghans - with fortified foods. Their strategy was to add vitamins and minerals such as iron, zinc, folic acid, Vitamin B-12 and Vitamin A to wheat flour, vegetable oil and ghee, and also to fortify salt with iodine. The project costs 6.4 million dollars.

The sums of money required to fund delivery of iodine and fortified foods to malnourished Afghan children should be compared, I believe, to the sums of money that the Pentagon's insatiable appetite for war-making has required of U.S. people.

The price tag for supplying iodized salt to one child for one year is 5 cents.

The cost of maintaining one U.S. soldier has recently risen to 2.1. million dollars per year. The amount of money spent to keep three U.S. soldiers in Afghanistan in 2014 could almost cover the cost of a four year program to deliver fortified foods to 15 million Afghan people.

Maj. Gen. Kurt J. Stein, who is overseeing the drawdown of U.S. troops from Afghanistan, has referred to the operation as "the largest retrograde mission in history." The mission will cost as much as $6 billion.

Over the past decade, spin doctors for U.S. military spending have suggested that Afghanistan needs the U.S. troop presence and U.S. non-military spending to protect the interests of women and children.

It's true that non-military aid to Afghanistan, sent by the U.S. since 2002, now approaches 100 billion dollars.

Several articles on Afghanistan's worsening hunger crisis, appearing in the Western press, prompt readers to ask how Afghanistan could be receiving vast sums of non-military aid and yet still struggle with severe acute malnourishment among children under age five.

However, a 2013 quarterly report to Congress submitted by the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan shows that, of the nearly $100 billion spent on wartime reconstruction, 97 billion has been spent on counter-narcotics, security, "governance/development" and "oversight and operations." No more than $3 billion, a hundred dollars per Afghan person, were used for "humanitarian" projects - to help keep thirty million Afghans alive through twelve years of U.S. war and occupation.

Funds have been available for tanks, guns, bullets, helicopters, missiles, weaponized drones, drone surveillance, Joint Special Operations task forces, bases, airstrips, prisons, and truck delivered supplies for tens of thousands of troops. But funds are in short supply for children too weak to cry who are battling for their lives while wasting away.

A whole generation of Afghans and other people around the developing world see the true results of Westerners' self-righteous claim for the need to keep civilians "safe" through war. They see the terror, entirely justified, filling Fatima's eyes in her hospital bed.

In that room in Kabul, as my friends learned about the stark realities of hunger -- and among them, I know, were some who worry about hunger in their own families -- I could see a rejection both of panic and of revenge in the eyes of the people around me. Their steady thoughtfulness was an inspiration.

Panic and revenge among far more prosperous people in the U.S. helped to drive the U.S. into a war waged against one of the poorest countries in the world. Yet, my Afghan friends, who've borne the brunt of war, long to rise above vengeance and narrow self-interest.

They wish to pursue a peace that includes ending hunger.

With us was Hakim, a medical doctor who spent six years working as a public health specialist in the central highlands of Afghanistan and, prior to that, among refugees in Quetta, Pakistan. He helped us understand conditions that lead to food shortages and taught us about diseases, such as kwashiorkor and marasmus, which are caused by insufficient protein or general malnutrition.

We looked at UN figures about hunger in Afghanistan which show malnutrition rates rising by 50% or more compared with 2012. The malnutrition ward at Helmand Province's Bost Hospital has been admitting 200 children a month for severe, acute malnutrition -- four times more than in January 2012.

A recent New York Times article about the worsening hunger crisis described an encounter with a mother and child in an Afghan hospital: "In another bed is Fatima, less than a year old, who is so severely malnourished that her heart is failing, and the doctors expect that she will soon die unless her father is able to find money to take her to Kabul for surgery. The girl's face bears a perpetual look of utter terror, and she rarely stops crying."

Photos of Fatima and other children in the ward accompanied the article. In our room in Kabul, Hakim projected the photos on the wall. They were painful to see and so were the nods of comprehension from Afghans all too familiar with the agonies of poverty in a time of war.

As children grow, they need iodine to enable proper brain development. According to a UNICEF/GAIN report, "iodine deficiency is the most prevalent cause of brain damage worldwide. It is easily preventable, and through ongoing targeted interventions, can be eliminated." As recently as 2009 we learned that 70% of Afghan children faced an iodine deficiency.

Universal Salt Iodization (USI) is recognized as a simple, safe and cost-effective measure in addressing iodine deficiency. The World Bank reports that it costs $.05 per child, per year.

In 2012, the World Food Programme (WFP) and the Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN) announced a four-year project which aimed to reach nearly half of Afghanistan's population - 15 million Afghans - with fortified foods. Their strategy was to add vitamins and minerals such as iron, zinc, folic acid, Vitamin B-12 and Vitamin A to wheat flour, vegetable oil and ghee, and also to fortify salt with iodine. The project costs 6.4 million dollars.

The sums of money required to fund delivery of iodine and fortified foods to malnourished Afghan children should be compared, I believe, to the sums of money that the Pentagon's insatiable appetite for war-making has required of U.S. people.

The price tag for supplying iodized salt to one child for one year is 5 cents.

The cost of maintaining one U.S. soldier has recently risen to 2.1. million dollars per year. The amount of money spent to keep three U.S. soldiers in Afghanistan in 2014 could almost cover the cost of a four year program to deliver fortified foods to 15 million Afghan people.

Maj. Gen. Kurt J. Stein, who is overseeing the drawdown of U.S. troops from Afghanistan, has referred to the operation as "the largest retrograde mission in history." The mission will cost as much as $6 billion.

Over the past decade, spin doctors for U.S. military spending have suggested that Afghanistan needs the U.S. troop presence and U.S. non-military spending to protect the interests of women and children.

It's true that non-military aid to Afghanistan, sent by the U.S. since 2002, now approaches 100 billion dollars.

Several articles on Afghanistan's worsening hunger crisis, appearing in the Western press, prompt readers to ask how Afghanistan could be receiving vast sums of non-military aid and yet still struggle with severe acute malnourishment among children under age five.

However, a 2013 quarterly report to Congress submitted by the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan shows that, of the nearly $100 billion spent on wartime reconstruction, 97 billion has been spent on counter-narcotics, security, "governance/development" and "oversight and operations." No more than $3 billion, a hundred dollars per Afghan person, were used for "humanitarian" projects - to help keep thirty million Afghans alive through twelve years of U.S. war and occupation.

Funds have been available for tanks, guns, bullets, helicopters, missiles, weaponized drones, drone surveillance, Joint Special Operations task forces, bases, airstrips, prisons, and truck delivered supplies for tens of thousands of troops. But funds are in short supply for children too weak to cry who are battling for their lives while wasting away.

A whole generation of Afghans and other people around the developing world see the true results of Westerners' self-righteous claim for the need to keep civilians "safe" through war. They see the terror, entirely justified, filling Fatima's eyes in her hospital bed.

In that room in Kabul, as my friends learned about the stark realities of hunger -- and among them, I know, were some who worry about hunger in their own families -- I could see a rejection both of panic and of revenge in the eyes of the people around me. Their steady thoughtfulness was an inspiration.

Panic and revenge among far more prosperous people in the U.S. helped to drive the U.S. into a war waged against one of the poorest countries in the world. Yet, my Afghan friends, who've borne the brunt of war, long to rise above vengeance and narrow self-interest.

They wish to pursue a peace that includes ending hunger.