SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

"People want peace so much that one of these days government had better get out of their way and let them have it."-- President Dwight D. Eisenhower

Just two weeks ago, the United States stood at the brink of yet another war. President Obama was announcing plans to order U.S. military strikes on Syria, with consequences that no one could predict.

Historians may look back at this as a moment when the people finally got the peace they demanded.

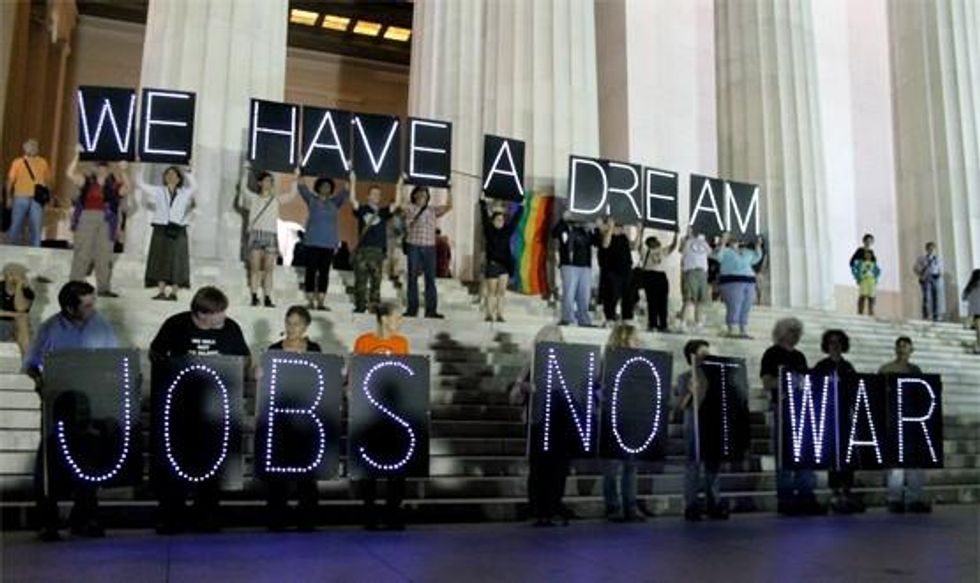

Then things shifted. In an extraordinarily short time, the people petitioned, called their representatives in Congress, held rallies, and used social media to demand a nonviolent approach to the crisis. The march toward war slowed.

During Tuesday night's address to the nation, President Obama said his administration will work with close allies, and with Russia and Syria, toward a diplomatic solution: pushing a resolution through the United Nations Security Council requiring the Syrian government to give up its chemical weapons. He also said the United States will give U.N. weapons inspectors a chance to report their findings on the chemical weapons attack of August 21.

If these diplomatic efforts to dismantle Syria's chemical weapons stockpiles are successful, historians may look back at this as a moment when the people finally got the peace they demanded.

On August 29, the British Parliament rejected a motion to authorize an assault on Syria, and Prime Minister David Cameron accepted the vote--even though he was not required to do so by law. The leading member of Parliament from the Labour Party, Ed Milliband, said he'd acted "for the people of Britain," who "want us to learn the lessons of Iraq."

To many ordinary Americans, it felt like a racing freight train had suddenly been brought to a halt.

In the United States, MoveOn.org--which usually supports President Obama--launched a campaign asking him to seek an alternative to military strikes in Syria.

"We have seen the rushed march to war before," Anna Galland, executive director of MoveOn.org Civil Action, said in a statement. "We cannot allow it again. Congress, and the nation, should not be forced into a binary debate over strikes or nothing."

Other groups joined in, such as VoteVets.org, the Progressive Change Campaign Committee, and US Action/True Majority. Meanwhile, Rep. Scott Rigell of Virginia and House Majority Leader John Boehner, both Republicans, circulated letters requesting that Congress be consulted prior to any military strikes. One hundred sixteen house members--both Republicans and Democrats--signed on.

And Obama listened. It's hard to say if he agreed to consult Congress prior to an attack because he felt the pressure, because he was getting cold feet about going to war, or because the War Powers Resolution, a federal law passed after the end of the Vietnam War, requires congressional approval for beginning a war. But on August 31, he announced he would turn to the U.S. Congress for authorization of military strikes.

Once the chemical weapons issue is settled, a peace conference should come next.

To many ordinary Americans, it felt like a racing freight train had suddenly been brought to a halt. The pause gave the public a chance to weigh in, and they showed up in force. Members of Congress reported an avalanche of calls and emails from constituents, almost all opposing military involvement. Many have questioned the usefulness of contacting members of Congress in recent years, as Washington, D.C., has become something of a corporate controlled bubble.

But this time, the message got through. As of September 9, the House was leaning heavily against authorizing military strikes, with only 42 out of 416 favoring or leaning towards a "yes" vote, according to a tally by Think Progress.

And public opinion polls show support for military involvement continues to drop; a new WSJ/NBC News survey shows that just a third of Americans support military intervention. Forty-seven percent say an attack is not in our national interest, up from 33 percent who said that a month ago (before the chemical attack took place).

Support among Republicans dropped especially steeply; today just 19 percent say a strike on Syria would be in the national interest.

While Congress was debating and fielding calls from constituents, military strikes were on hold. Then, Secretary of State John Kerry opened the door to diplomacy, saying that if Syria were to dispose of its chemical weapons cache, military action could be averted. That idea was quickly embraced by Russia and Syria. The agreement that's currently being hashed out may turn out to be the breakthrough that allows the United States to back down from a potentially catastrophic military incursion.

Chemical weapons are, of course, just one part of the Syrian conflict. The violence there continues; millions have been displaced, tens of thousands are dead, and thousands more are under threat of injury or death. And the conflict still may spread to involve more of the region.

To make this temporary reprieve from a scaled-up war into real peace, the diplomacy must build on this tenuous opening. Once the chemical weapons issue is settled, a peace conference should come next, sponsored by the U.N. Security Council and involving not only Syria and the various opposition forces, but those countries and organizations actively supporting all sides of the conflict. (See Syria: Six Alternatives to Military Strikes.)

Successful diplomacy will help those within Syria seeking a lawful and peaceful transition beyond the conflict. And the effect will spill out beyond Syria and beyond the Middle East. Effective resolution of international conflicts within the rule of law--under the auspices of the international institutions designed for that purpose--will build the confidence and the capacities we'll need to solve the next set of conflicts without war.

Doing so will generate all sorts of spin-off effects. Peaceful and lawful diplomacy has far fewer secrets to keep, so it removes much of the justification for a centralized security state, NSA wiretaps, secret surveillance, and other threats to our freedom.

And the peace dividend we get when we stay clear of war allows us to invest in solving the profound problems that confront all our societies, including poverty, inequality, and the climate crisis.

This is clearly what the American people and the people of the world are saying they want, and, for once, they seem to be getting it.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

"People want peace so much that one of these days government had better get out of their way and let them have it."-- President Dwight D. Eisenhower

Just two weeks ago, the United States stood at the brink of yet another war. President Obama was announcing plans to order U.S. military strikes on Syria, with consequences that no one could predict.

Historians may look back at this as a moment when the people finally got the peace they demanded.

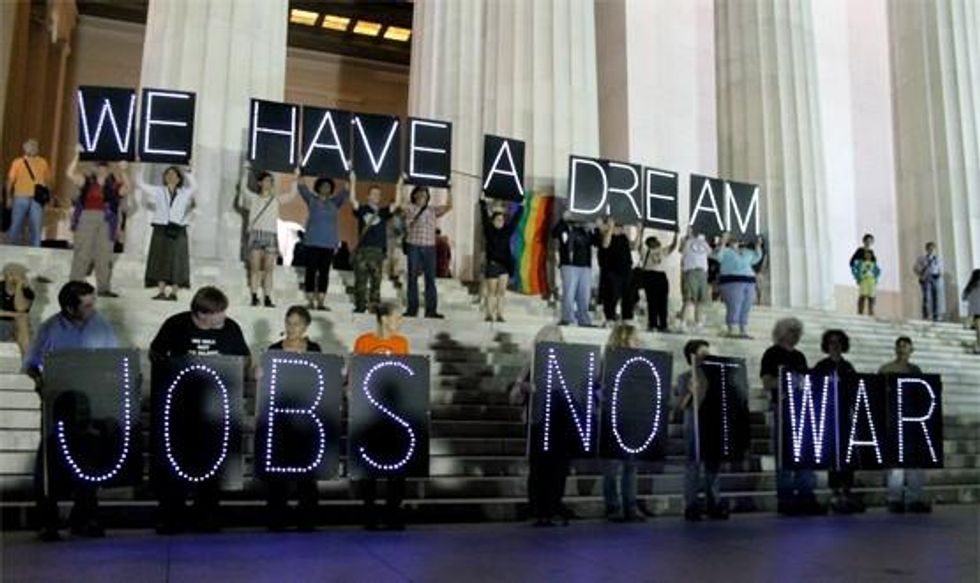

Then things shifted. In an extraordinarily short time, the people petitioned, called their representatives in Congress, held rallies, and used social media to demand a nonviolent approach to the crisis. The march toward war slowed.

During Tuesday night's address to the nation, President Obama said his administration will work with close allies, and with Russia and Syria, toward a diplomatic solution: pushing a resolution through the United Nations Security Council requiring the Syrian government to give up its chemical weapons. He also said the United States will give U.N. weapons inspectors a chance to report their findings on the chemical weapons attack of August 21.

If these diplomatic efforts to dismantle Syria's chemical weapons stockpiles are successful, historians may look back at this as a moment when the people finally got the peace they demanded.

On August 29, the British Parliament rejected a motion to authorize an assault on Syria, and Prime Minister David Cameron accepted the vote--even though he was not required to do so by law. The leading member of Parliament from the Labour Party, Ed Milliband, said he'd acted "for the people of Britain," who "want us to learn the lessons of Iraq."

To many ordinary Americans, it felt like a racing freight train had suddenly been brought to a halt.

In the United States, MoveOn.org--which usually supports President Obama--launched a campaign asking him to seek an alternative to military strikes in Syria.

"We have seen the rushed march to war before," Anna Galland, executive director of MoveOn.org Civil Action, said in a statement. "We cannot allow it again. Congress, and the nation, should not be forced into a binary debate over strikes or nothing."

Other groups joined in, such as VoteVets.org, the Progressive Change Campaign Committee, and US Action/True Majority. Meanwhile, Rep. Scott Rigell of Virginia and House Majority Leader John Boehner, both Republicans, circulated letters requesting that Congress be consulted prior to any military strikes. One hundred sixteen house members--both Republicans and Democrats--signed on.

And Obama listened. It's hard to say if he agreed to consult Congress prior to an attack because he felt the pressure, because he was getting cold feet about going to war, or because the War Powers Resolution, a federal law passed after the end of the Vietnam War, requires congressional approval for beginning a war. But on August 31, he announced he would turn to the U.S. Congress for authorization of military strikes.

Once the chemical weapons issue is settled, a peace conference should come next.

To many ordinary Americans, it felt like a racing freight train had suddenly been brought to a halt. The pause gave the public a chance to weigh in, and they showed up in force. Members of Congress reported an avalanche of calls and emails from constituents, almost all opposing military involvement. Many have questioned the usefulness of contacting members of Congress in recent years, as Washington, D.C., has become something of a corporate controlled bubble.

But this time, the message got through. As of September 9, the House was leaning heavily against authorizing military strikes, with only 42 out of 416 favoring or leaning towards a "yes" vote, according to a tally by Think Progress.

And public opinion polls show support for military involvement continues to drop; a new WSJ/NBC News survey shows that just a third of Americans support military intervention. Forty-seven percent say an attack is not in our national interest, up from 33 percent who said that a month ago (before the chemical attack took place).

Support among Republicans dropped especially steeply; today just 19 percent say a strike on Syria would be in the national interest.

While Congress was debating and fielding calls from constituents, military strikes were on hold. Then, Secretary of State John Kerry opened the door to diplomacy, saying that if Syria were to dispose of its chemical weapons cache, military action could be averted. That idea was quickly embraced by Russia and Syria. The agreement that's currently being hashed out may turn out to be the breakthrough that allows the United States to back down from a potentially catastrophic military incursion.

Chemical weapons are, of course, just one part of the Syrian conflict. The violence there continues; millions have been displaced, tens of thousands are dead, and thousands more are under threat of injury or death. And the conflict still may spread to involve more of the region.

To make this temporary reprieve from a scaled-up war into real peace, the diplomacy must build on this tenuous opening. Once the chemical weapons issue is settled, a peace conference should come next, sponsored by the U.N. Security Council and involving not only Syria and the various opposition forces, but those countries and organizations actively supporting all sides of the conflict. (See Syria: Six Alternatives to Military Strikes.)

Successful diplomacy will help those within Syria seeking a lawful and peaceful transition beyond the conflict. And the effect will spill out beyond Syria and beyond the Middle East. Effective resolution of international conflicts within the rule of law--under the auspices of the international institutions designed for that purpose--will build the confidence and the capacities we'll need to solve the next set of conflicts without war.

Doing so will generate all sorts of spin-off effects. Peaceful and lawful diplomacy has far fewer secrets to keep, so it removes much of the justification for a centralized security state, NSA wiretaps, secret surveillance, and other threats to our freedom.

And the peace dividend we get when we stay clear of war allows us to invest in solving the profound problems that confront all our societies, including poverty, inequality, and the climate crisis.

This is clearly what the American people and the people of the world are saying they want, and, for once, they seem to be getting it.

"People want peace so much that one of these days government had better get out of their way and let them have it."-- President Dwight D. Eisenhower

Just two weeks ago, the United States stood at the brink of yet another war. President Obama was announcing plans to order U.S. military strikes on Syria, with consequences that no one could predict.

Historians may look back at this as a moment when the people finally got the peace they demanded.

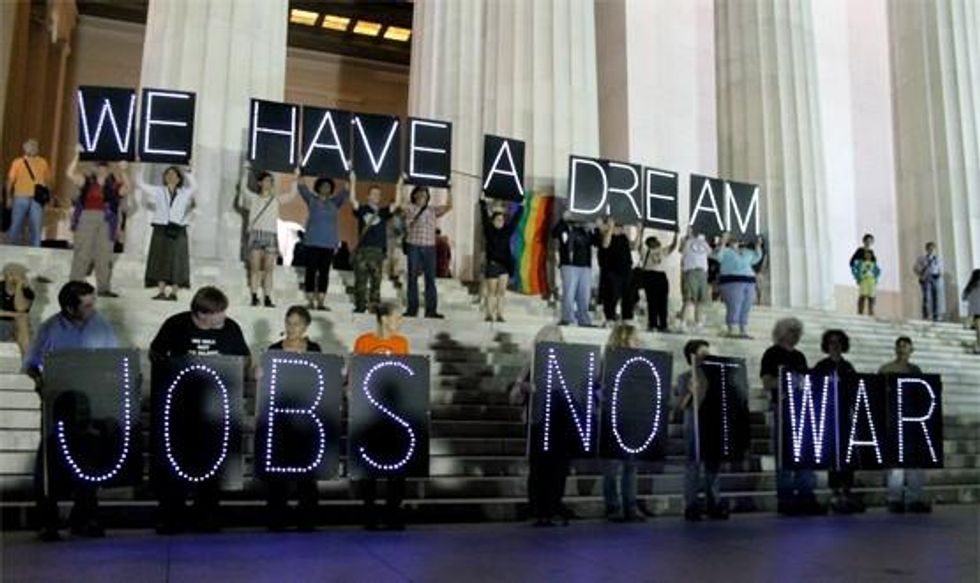

Then things shifted. In an extraordinarily short time, the people petitioned, called their representatives in Congress, held rallies, and used social media to demand a nonviolent approach to the crisis. The march toward war slowed.

During Tuesday night's address to the nation, President Obama said his administration will work with close allies, and with Russia and Syria, toward a diplomatic solution: pushing a resolution through the United Nations Security Council requiring the Syrian government to give up its chemical weapons. He also said the United States will give U.N. weapons inspectors a chance to report their findings on the chemical weapons attack of August 21.

If these diplomatic efforts to dismantle Syria's chemical weapons stockpiles are successful, historians may look back at this as a moment when the people finally got the peace they demanded.

On August 29, the British Parliament rejected a motion to authorize an assault on Syria, and Prime Minister David Cameron accepted the vote--even though he was not required to do so by law. The leading member of Parliament from the Labour Party, Ed Milliband, said he'd acted "for the people of Britain," who "want us to learn the lessons of Iraq."

To many ordinary Americans, it felt like a racing freight train had suddenly been brought to a halt.

In the United States, MoveOn.org--which usually supports President Obama--launched a campaign asking him to seek an alternative to military strikes in Syria.

"We have seen the rushed march to war before," Anna Galland, executive director of MoveOn.org Civil Action, said in a statement. "We cannot allow it again. Congress, and the nation, should not be forced into a binary debate over strikes or nothing."

Other groups joined in, such as VoteVets.org, the Progressive Change Campaign Committee, and US Action/True Majority. Meanwhile, Rep. Scott Rigell of Virginia and House Majority Leader John Boehner, both Republicans, circulated letters requesting that Congress be consulted prior to any military strikes. One hundred sixteen house members--both Republicans and Democrats--signed on.

And Obama listened. It's hard to say if he agreed to consult Congress prior to an attack because he felt the pressure, because he was getting cold feet about going to war, or because the War Powers Resolution, a federal law passed after the end of the Vietnam War, requires congressional approval for beginning a war. But on August 31, he announced he would turn to the U.S. Congress for authorization of military strikes.

Once the chemical weapons issue is settled, a peace conference should come next.

To many ordinary Americans, it felt like a racing freight train had suddenly been brought to a halt. The pause gave the public a chance to weigh in, and they showed up in force. Members of Congress reported an avalanche of calls and emails from constituents, almost all opposing military involvement. Many have questioned the usefulness of contacting members of Congress in recent years, as Washington, D.C., has become something of a corporate controlled bubble.

But this time, the message got through. As of September 9, the House was leaning heavily against authorizing military strikes, with only 42 out of 416 favoring or leaning towards a "yes" vote, according to a tally by Think Progress.

And public opinion polls show support for military involvement continues to drop; a new WSJ/NBC News survey shows that just a third of Americans support military intervention. Forty-seven percent say an attack is not in our national interest, up from 33 percent who said that a month ago (before the chemical attack took place).

Support among Republicans dropped especially steeply; today just 19 percent say a strike on Syria would be in the national interest.

While Congress was debating and fielding calls from constituents, military strikes were on hold. Then, Secretary of State John Kerry opened the door to diplomacy, saying that if Syria were to dispose of its chemical weapons cache, military action could be averted. That idea was quickly embraced by Russia and Syria. The agreement that's currently being hashed out may turn out to be the breakthrough that allows the United States to back down from a potentially catastrophic military incursion.

Chemical weapons are, of course, just one part of the Syrian conflict. The violence there continues; millions have been displaced, tens of thousands are dead, and thousands more are under threat of injury or death. And the conflict still may spread to involve more of the region.

To make this temporary reprieve from a scaled-up war into real peace, the diplomacy must build on this tenuous opening. Once the chemical weapons issue is settled, a peace conference should come next, sponsored by the U.N. Security Council and involving not only Syria and the various opposition forces, but those countries and organizations actively supporting all sides of the conflict. (See Syria: Six Alternatives to Military Strikes.)

Successful diplomacy will help those within Syria seeking a lawful and peaceful transition beyond the conflict. And the effect will spill out beyond Syria and beyond the Middle East. Effective resolution of international conflicts within the rule of law--under the auspices of the international institutions designed for that purpose--will build the confidence and the capacities we'll need to solve the next set of conflicts without war.

Doing so will generate all sorts of spin-off effects. Peaceful and lawful diplomacy has far fewer secrets to keep, so it removes much of the justification for a centralized security state, NSA wiretaps, secret surveillance, and other threats to our freedom.

And the peace dividend we get when we stay clear of war allows us to invest in solving the profound problems that confront all our societies, including poverty, inequality, and the climate crisis.

This is clearly what the American people and the people of the world are saying they want, and, for once, they seem to be getting it.