Sam Lovejoy, the No Nukes Movement, and the Tower that Toppled a Terrible Technology

There it stood, 500 feet of insult and injury. And then it crashed to the ground.

The weather tower at the proposed Montague double-reactor complex was meant to test wind direction in case of an accident. In early 1974, the project was estimated at $1.35 billion, as much as double the entire assessed value of all the real estate in this rural Connecticut Valley town, 90 miles west of Boston. Then--39 years ago this week--Sam Lovejoy knocked it down.

Lovejoy lived at the old Liberation News Service farm, four miles from the site. Montague's population of about 7500 included a growing number of "hippie communes." As documented in Ray Mungo's Famous Long Ago, this one was born of a radical news service that had been infiltrated by the FBI, promoting a legendary split that led the founding faction to flee to rural Massachusetts.

And thus J. Edgar Hoover--may he spin in his grave over this one--became an inadvertent godfather to the movement against nuclear power.

When the local utility announced it would build atomic reactors on the eastern shore of the Connecticut River, 180 miles north of New York City, they thought they were waltzing into a docile rural community. But many of the local communes were pioneering a new generation's movement for organic farming, and were well-stocked with seasoned activists still working in the peace and civil rights movements. Radioactive fallout was not in synch with our new-found aversion to chemical sprays and fertilizers. Over the next three decades, this reborn organic ethos would help spawn a major on-going shift in the public view toward holistic food that continues today.

For those of us at Montague Farm, the idea of two gargantuan reactors four miles from our lovely young children, Eben and Sequoyah, our pristine one-acre garden and glorious maple sugar bush... all this and more prompted two clear, uncompromising words: NO NUKES!

We printed the first bumper stickers, drafted pamphlets and began organizing.

Nobody believed we could beat a massive corporation with more money than Lucifer. An initial poll showed three-quarters of the town in favor of the jobs, tax breaks and excitement the reactors would bring. For us, one out of four of our neighbors was a pretty good start.

But nationwide, when Richard Nixon said there'd be 1000 US reactors by the year 2000, nobody doubted him. Nuclear power was a popular assumption, a given supported by a large majority of the world's population. We needed a jolt to get our movement off the ground.

That would be the tower. All day and night it blinked on and off, ostensibly in warning to small planes flying in and out of the Turners Falls Airport. But it also stood as a symbol of arrogance and oppression, a steel calling card from a corporation that could not care less about our health, safety or organic well-being.

So at 4 am on Washington's Birthday (which back then was still February 22), Sam knocked it down. In a feat of mechanical daring many of us still find daunting, he carefully used a crow bar to unfasten one...then two...then a third turnbuckle. The wires on the other two sides of the triangulated support system then pulled down six of the tower's seven segments, leaving just one 70-foot stump still standing. It was so loud, Sam said, he was "amazed the whole town didn't wake up."

But this was the Montague Plains, the middle of nowhere. Sam ran to the road and flagged down the first car--it happened to be a police cruiser--and asked for a ride to the Turners Falls station. Atomic energy, said his typed statement, was dangerous, dirty, expensive, unneeded and, above all, a threat to our children. Tearing down the tower was a legitimate means of protecting the community.

This being Massachusetts, Sam was freed later that morning on his personal promise to return for trial. Facing a felony charge in September, he was acquitted on a technicality. A jury poll showed he would have been let go anyway.

The legendary historian Howard Zinn testified on Sam's behalf. So did Dr. John Gofman, first health director of the Atomic Energy Commission, who flew from California to warn this small-town jury that the atomic reactors he helped invent were instruments of what he called "mass murder."

The tower toppling and subsequent trial were pure, picturesque reborn Henry Thoreau, whose beloved Walden Pond is just 50 miles down wind.

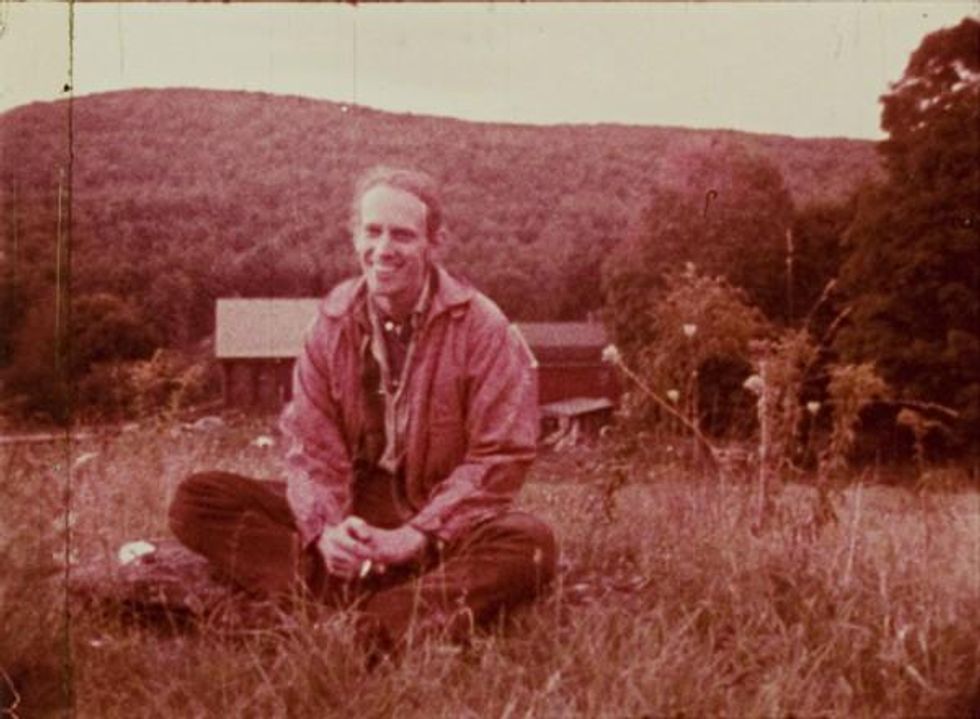

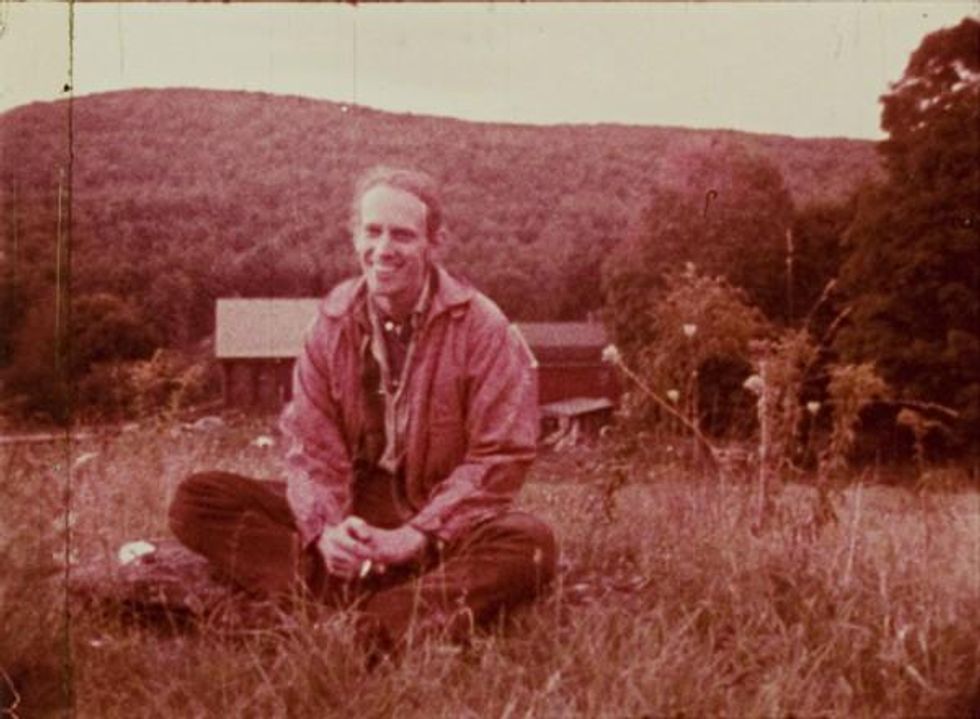

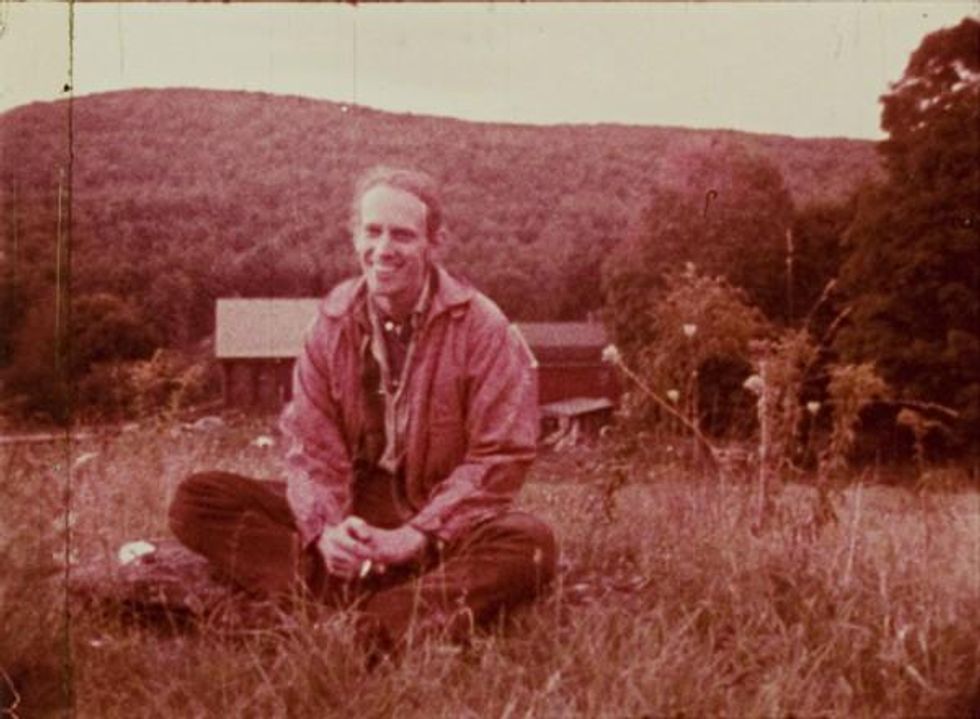

Sam was the perfect hero. Brilliant, charismatic, funny and unaffected, his combination of rural roots and an Amherst College degree made him an irresistible spokesperson for the nascent No Nukes campaign.

Backed by a community packed with activists, organizers, writers and journalists, the word spread like wildfire. Filmmaker Dan Keller, an Amherst classmate, made Green Mountain Post's award-winning Lovejoy's Nuclear War, produced on a shoe string, seen by millions on public television, at rallies, speeches, library gatherings, classrooms and more throughout the US, Europe and Japan. For a critical mass of citizen-activists, it was the first introduction to an issue on which the fate of the Earth had quietly hinged.

In 1975, Montague Farmer Fran Koster helped organize a "Toward Tomorrow" Fair in Amherst that featured green energy pioneer Amory Lovins and early wind advocate William Heronemus. A vision emerged of a Solartopian energy future, built entirely around renewables and efficiency, free of "King CONG"--coal, oil, nukes and gas.

Then the Clamshell Alliance took root in coastal New Hampshire. Dedicated to mass non-violent civil disobedience, the Clam began organizing the first mass protests against twin reactors proposed for Seabrook. In 1977, 1414 were arrested at the site. More than a thousand were locked up in National Guard armories, with some 550 protestors still there two weeks later.

Global saturation media coverage helped the Clam spawn dozens of sibling alliances. A truly national No Nukes movement was born.

On June 24, 1978, the Clam drew 20,000 citizens to a legal rally on the Seabrook site that featured Pete Seeger, Jackson Browne, John Hall and others. Nine months prior to Three Mile Island, it was the biggest US No Nukes gathering to that time.

So when the 1979 melt-down at TMI did occur, there was a feature film--The China Syndrome--and a critical mass of opposition firmly in place. As the entire northeast shuddered in fear, public opinion definitively shifted away from atomic energy.

That September, "No Nukes" concerts in New York featured Bonnie Raitt, Jackson Browne, Graham Nash, Bruce Springsteen, James Taylor and many more. Some 200,000 people rallied at Battery Park City (now the site of a pioneer solar housing development). The "No Nukes" feature film and platinum album helped certify mainstream opposition to atomic energy.

Today, in the wake of Chernobyl, Fukushima and decades of organizing, atomic energy is in steep decline. Nixon's promised 1000 reactors became 104, with at least two more to shut this year. New construction is virtually dead in Europe, with Germany rapidly converting to the Solartopian future promised so clearly in Amherst back in 1975.

Sam Lovejoy has kept the faith over the years, working for the state of Massachusetts to preserve environmentally sensitive land--including the Montague Plains, once targeted for a massive reactor complex, now an undisturbed piece of pristine parkland.

Dan Keller still farms organically, and still makes films, including a recent "Solartopia" YouTube starring Pete Seeger. Nina Keller, Francis Crowe, Randy Kehler, Betsy Corner, Deb Katz, Claire Chang, Janice Frey and other Montague Farmers and local activists are in their 40th year of No Nukes activism, aimed largely at shutting nearby Vermont Yankee--a victory that soon may be won. Anna Gyorgy, author of the 1979 "No Nukes" sourcebook, writes from Bonn on Germany's epic shift away from atomic power and toward renewables.

Rare amongst the era's communes, Montague Farm has survived intact. In an evolutionary leap, it became the base for the Zen Peacemaker organization of Roshi Bernie Glassman and Eve Marko. They preserved the land, saved the farmhouse, converted the ancient barn to an astonishing meditation center, and culminated their stay with a landmark gathering on Socially Engaged Buddhism. A new generation of owners is now making the place into a green conference center.

Like Montague Farm, the No Nukes movement still sustains its fair share of diverse opinions. But its commitment to non-violence has deepened, as has its impact on the nuclear industry. Among other things, it's forced open the financial and demand space for an epic expansion of Solartopian technologies--especially solar and wind, which are now significantly cheaper than nukes.

In the wake of that, and of Fukushima, new reactor construction is largely on the ropes in Europe and the US. But President Obama may now nominate a pro-nuclear Secretary of Energy. More than 400 deteriorating reactors still run worldwide, with escalating danger to us all. China, Russia, and South Korea still seem committed to new ones, as does India, where grassroots resistance is fierce.

There's also talk of a new generation of smaller reactors which are unproven, untested, and unlikely to succeed. The decades have taught us that money spent on any form of atomic energy (except for clean-up) means vital resources stripped from the Solartopian technologies we need to survive.

We've also learned that a single act of courage, in concert with a community of dedicated organizers, can change the world. The No Nukes movement continues to succeed with an epic commitment to creative non-violence.

In terms of technology, cost and do-ability, Solartopia is within our grasp. Politically, our ultimate challenge comes with the demand to sustain the daring, wisdom and organic zeal needed to win a green-powered Earth.

For that, we'll do well to remember the sound of one tower crashing.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

There it stood, 500 feet of insult and injury. And then it crashed to the ground.

The weather tower at the proposed Montague double-reactor complex was meant to test wind direction in case of an accident. In early 1974, the project was estimated at $1.35 billion, as much as double the entire assessed value of all the real estate in this rural Connecticut Valley town, 90 miles west of Boston. Then--39 years ago this week--Sam Lovejoy knocked it down.

Lovejoy lived at the old Liberation News Service farm, four miles from the site. Montague's population of about 7500 included a growing number of "hippie communes." As documented in Ray Mungo's Famous Long Ago, this one was born of a radical news service that had been infiltrated by the FBI, promoting a legendary split that led the founding faction to flee to rural Massachusetts.

And thus J. Edgar Hoover--may he spin in his grave over this one--became an inadvertent godfather to the movement against nuclear power.

When the local utility announced it would build atomic reactors on the eastern shore of the Connecticut River, 180 miles north of New York City, they thought they were waltzing into a docile rural community. But many of the local communes were pioneering a new generation's movement for organic farming, and were well-stocked with seasoned activists still working in the peace and civil rights movements. Radioactive fallout was not in synch with our new-found aversion to chemical sprays and fertilizers. Over the next three decades, this reborn organic ethos would help spawn a major on-going shift in the public view toward holistic food that continues today.

For those of us at Montague Farm, the idea of two gargantuan reactors four miles from our lovely young children, Eben and Sequoyah, our pristine one-acre garden and glorious maple sugar bush... all this and more prompted two clear, uncompromising words: NO NUKES!

We printed the first bumper stickers, drafted pamphlets and began organizing.

Nobody believed we could beat a massive corporation with more money than Lucifer. An initial poll showed three-quarters of the town in favor of the jobs, tax breaks and excitement the reactors would bring. For us, one out of four of our neighbors was a pretty good start.

But nationwide, when Richard Nixon said there'd be 1000 US reactors by the year 2000, nobody doubted him. Nuclear power was a popular assumption, a given supported by a large majority of the world's population. We needed a jolt to get our movement off the ground.

That would be the tower. All day and night it blinked on and off, ostensibly in warning to small planes flying in and out of the Turners Falls Airport. But it also stood as a symbol of arrogance and oppression, a steel calling card from a corporation that could not care less about our health, safety or organic well-being.

So at 4 am on Washington's Birthday (which back then was still February 22), Sam knocked it down. In a feat of mechanical daring many of us still find daunting, he carefully used a crow bar to unfasten one...then two...then a third turnbuckle. The wires on the other two sides of the triangulated support system then pulled down six of the tower's seven segments, leaving just one 70-foot stump still standing. It was so loud, Sam said, he was "amazed the whole town didn't wake up."

But this was the Montague Plains, the middle of nowhere. Sam ran to the road and flagged down the first car--it happened to be a police cruiser--and asked for a ride to the Turners Falls station. Atomic energy, said his typed statement, was dangerous, dirty, expensive, unneeded and, above all, a threat to our children. Tearing down the tower was a legitimate means of protecting the community.

This being Massachusetts, Sam was freed later that morning on his personal promise to return for trial. Facing a felony charge in September, he was acquitted on a technicality. A jury poll showed he would have been let go anyway.

The legendary historian Howard Zinn testified on Sam's behalf. So did Dr. John Gofman, first health director of the Atomic Energy Commission, who flew from California to warn this small-town jury that the atomic reactors he helped invent were instruments of what he called "mass murder."

The tower toppling and subsequent trial were pure, picturesque reborn Henry Thoreau, whose beloved Walden Pond is just 50 miles down wind.

Sam was the perfect hero. Brilliant, charismatic, funny and unaffected, his combination of rural roots and an Amherst College degree made him an irresistible spokesperson for the nascent No Nukes campaign.

Backed by a community packed with activists, organizers, writers and journalists, the word spread like wildfire. Filmmaker Dan Keller, an Amherst classmate, made Green Mountain Post's award-winning Lovejoy's Nuclear War, produced on a shoe string, seen by millions on public television, at rallies, speeches, library gatherings, classrooms and more throughout the US, Europe and Japan. For a critical mass of citizen-activists, it was the first introduction to an issue on which the fate of the Earth had quietly hinged.

In 1975, Montague Farmer Fran Koster helped organize a "Toward Tomorrow" Fair in Amherst that featured green energy pioneer Amory Lovins and early wind advocate William Heronemus. A vision emerged of a Solartopian energy future, built entirely around renewables and efficiency, free of "King CONG"--coal, oil, nukes and gas.

Then the Clamshell Alliance took root in coastal New Hampshire. Dedicated to mass non-violent civil disobedience, the Clam began organizing the first mass protests against twin reactors proposed for Seabrook. In 1977, 1414 were arrested at the site. More than a thousand were locked up in National Guard armories, with some 550 protestors still there two weeks later.

Global saturation media coverage helped the Clam spawn dozens of sibling alliances. A truly national No Nukes movement was born.

On June 24, 1978, the Clam drew 20,000 citizens to a legal rally on the Seabrook site that featured Pete Seeger, Jackson Browne, John Hall and others. Nine months prior to Three Mile Island, it was the biggest US No Nukes gathering to that time.

So when the 1979 melt-down at TMI did occur, there was a feature film--The China Syndrome--and a critical mass of opposition firmly in place. As the entire northeast shuddered in fear, public opinion definitively shifted away from atomic energy.

That September, "No Nukes" concerts in New York featured Bonnie Raitt, Jackson Browne, Graham Nash, Bruce Springsteen, James Taylor and many more. Some 200,000 people rallied at Battery Park City (now the site of a pioneer solar housing development). The "No Nukes" feature film and platinum album helped certify mainstream opposition to atomic energy.

Today, in the wake of Chernobyl, Fukushima and decades of organizing, atomic energy is in steep decline. Nixon's promised 1000 reactors became 104, with at least two more to shut this year. New construction is virtually dead in Europe, with Germany rapidly converting to the Solartopian future promised so clearly in Amherst back in 1975.

Sam Lovejoy has kept the faith over the years, working for the state of Massachusetts to preserve environmentally sensitive land--including the Montague Plains, once targeted for a massive reactor complex, now an undisturbed piece of pristine parkland.

Dan Keller still farms organically, and still makes films, including a recent "Solartopia" YouTube starring Pete Seeger. Nina Keller, Francis Crowe, Randy Kehler, Betsy Corner, Deb Katz, Claire Chang, Janice Frey and other Montague Farmers and local activists are in their 40th year of No Nukes activism, aimed largely at shutting nearby Vermont Yankee--a victory that soon may be won. Anna Gyorgy, author of the 1979 "No Nukes" sourcebook, writes from Bonn on Germany's epic shift away from atomic power and toward renewables.

Rare amongst the era's communes, Montague Farm has survived intact. In an evolutionary leap, it became the base for the Zen Peacemaker organization of Roshi Bernie Glassman and Eve Marko. They preserved the land, saved the farmhouse, converted the ancient barn to an astonishing meditation center, and culminated their stay with a landmark gathering on Socially Engaged Buddhism. A new generation of owners is now making the place into a green conference center.

Like Montague Farm, the No Nukes movement still sustains its fair share of diverse opinions. But its commitment to non-violence has deepened, as has its impact on the nuclear industry. Among other things, it's forced open the financial and demand space for an epic expansion of Solartopian technologies--especially solar and wind, which are now significantly cheaper than nukes.

In the wake of that, and of Fukushima, new reactor construction is largely on the ropes in Europe and the US. But President Obama may now nominate a pro-nuclear Secretary of Energy. More than 400 deteriorating reactors still run worldwide, with escalating danger to us all. China, Russia, and South Korea still seem committed to new ones, as does India, where grassroots resistance is fierce.

There's also talk of a new generation of smaller reactors which are unproven, untested, and unlikely to succeed. The decades have taught us that money spent on any form of atomic energy (except for clean-up) means vital resources stripped from the Solartopian technologies we need to survive.

We've also learned that a single act of courage, in concert with a community of dedicated organizers, can change the world. The No Nukes movement continues to succeed with an epic commitment to creative non-violence.

In terms of technology, cost and do-ability, Solartopia is within our grasp. Politically, our ultimate challenge comes with the demand to sustain the daring, wisdom and organic zeal needed to win a green-powered Earth.

For that, we'll do well to remember the sound of one tower crashing.

There it stood, 500 feet of insult and injury. And then it crashed to the ground.

The weather tower at the proposed Montague double-reactor complex was meant to test wind direction in case of an accident. In early 1974, the project was estimated at $1.35 billion, as much as double the entire assessed value of all the real estate in this rural Connecticut Valley town, 90 miles west of Boston. Then--39 years ago this week--Sam Lovejoy knocked it down.

Lovejoy lived at the old Liberation News Service farm, four miles from the site. Montague's population of about 7500 included a growing number of "hippie communes." As documented in Ray Mungo's Famous Long Ago, this one was born of a radical news service that had been infiltrated by the FBI, promoting a legendary split that led the founding faction to flee to rural Massachusetts.

And thus J. Edgar Hoover--may he spin in his grave over this one--became an inadvertent godfather to the movement against nuclear power.

When the local utility announced it would build atomic reactors on the eastern shore of the Connecticut River, 180 miles north of New York City, they thought they were waltzing into a docile rural community. But many of the local communes were pioneering a new generation's movement for organic farming, and were well-stocked with seasoned activists still working in the peace and civil rights movements. Radioactive fallout was not in synch with our new-found aversion to chemical sprays and fertilizers. Over the next three decades, this reborn organic ethos would help spawn a major on-going shift in the public view toward holistic food that continues today.

For those of us at Montague Farm, the idea of two gargantuan reactors four miles from our lovely young children, Eben and Sequoyah, our pristine one-acre garden and glorious maple sugar bush... all this and more prompted two clear, uncompromising words: NO NUKES!

We printed the first bumper stickers, drafted pamphlets and began organizing.

Nobody believed we could beat a massive corporation with more money than Lucifer. An initial poll showed three-quarters of the town in favor of the jobs, tax breaks and excitement the reactors would bring. For us, one out of four of our neighbors was a pretty good start.

But nationwide, when Richard Nixon said there'd be 1000 US reactors by the year 2000, nobody doubted him. Nuclear power was a popular assumption, a given supported by a large majority of the world's population. We needed a jolt to get our movement off the ground.

That would be the tower. All day and night it blinked on and off, ostensibly in warning to small planes flying in and out of the Turners Falls Airport. But it also stood as a symbol of arrogance and oppression, a steel calling card from a corporation that could not care less about our health, safety or organic well-being.

So at 4 am on Washington's Birthday (which back then was still February 22), Sam knocked it down. In a feat of mechanical daring many of us still find daunting, he carefully used a crow bar to unfasten one...then two...then a third turnbuckle. The wires on the other two sides of the triangulated support system then pulled down six of the tower's seven segments, leaving just one 70-foot stump still standing. It was so loud, Sam said, he was "amazed the whole town didn't wake up."

But this was the Montague Plains, the middle of nowhere. Sam ran to the road and flagged down the first car--it happened to be a police cruiser--and asked for a ride to the Turners Falls station. Atomic energy, said his typed statement, was dangerous, dirty, expensive, unneeded and, above all, a threat to our children. Tearing down the tower was a legitimate means of protecting the community.

This being Massachusetts, Sam was freed later that morning on his personal promise to return for trial. Facing a felony charge in September, he was acquitted on a technicality. A jury poll showed he would have been let go anyway.

The legendary historian Howard Zinn testified on Sam's behalf. So did Dr. John Gofman, first health director of the Atomic Energy Commission, who flew from California to warn this small-town jury that the atomic reactors he helped invent were instruments of what he called "mass murder."

The tower toppling and subsequent trial were pure, picturesque reborn Henry Thoreau, whose beloved Walden Pond is just 50 miles down wind.

Sam was the perfect hero. Brilliant, charismatic, funny and unaffected, his combination of rural roots and an Amherst College degree made him an irresistible spokesperson for the nascent No Nukes campaign.

Backed by a community packed with activists, organizers, writers and journalists, the word spread like wildfire. Filmmaker Dan Keller, an Amherst classmate, made Green Mountain Post's award-winning Lovejoy's Nuclear War, produced on a shoe string, seen by millions on public television, at rallies, speeches, library gatherings, classrooms and more throughout the US, Europe and Japan. For a critical mass of citizen-activists, it was the first introduction to an issue on which the fate of the Earth had quietly hinged.

In 1975, Montague Farmer Fran Koster helped organize a "Toward Tomorrow" Fair in Amherst that featured green energy pioneer Amory Lovins and early wind advocate William Heronemus. A vision emerged of a Solartopian energy future, built entirely around renewables and efficiency, free of "King CONG"--coal, oil, nukes and gas.

Then the Clamshell Alliance took root in coastal New Hampshire. Dedicated to mass non-violent civil disobedience, the Clam began organizing the first mass protests against twin reactors proposed for Seabrook. In 1977, 1414 were arrested at the site. More than a thousand were locked up in National Guard armories, with some 550 protestors still there two weeks later.

Global saturation media coverage helped the Clam spawn dozens of sibling alliances. A truly national No Nukes movement was born.

On June 24, 1978, the Clam drew 20,000 citizens to a legal rally on the Seabrook site that featured Pete Seeger, Jackson Browne, John Hall and others. Nine months prior to Three Mile Island, it was the biggest US No Nukes gathering to that time.

So when the 1979 melt-down at TMI did occur, there was a feature film--The China Syndrome--and a critical mass of opposition firmly in place. As the entire northeast shuddered in fear, public opinion definitively shifted away from atomic energy.

That September, "No Nukes" concerts in New York featured Bonnie Raitt, Jackson Browne, Graham Nash, Bruce Springsteen, James Taylor and many more. Some 200,000 people rallied at Battery Park City (now the site of a pioneer solar housing development). The "No Nukes" feature film and platinum album helped certify mainstream opposition to atomic energy.

Today, in the wake of Chernobyl, Fukushima and decades of organizing, atomic energy is in steep decline. Nixon's promised 1000 reactors became 104, with at least two more to shut this year. New construction is virtually dead in Europe, with Germany rapidly converting to the Solartopian future promised so clearly in Amherst back in 1975.

Sam Lovejoy has kept the faith over the years, working for the state of Massachusetts to preserve environmentally sensitive land--including the Montague Plains, once targeted for a massive reactor complex, now an undisturbed piece of pristine parkland.

Dan Keller still farms organically, and still makes films, including a recent "Solartopia" YouTube starring Pete Seeger. Nina Keller, Francis Crowe, Randy Kehler, Betsy Corner, Deb Katz, Claire Chang, Janice Frey and other Montague Farmers and local activists are in their 40th year of No Nukes activism, aimed largely at shutting nearby Vermont Yankee--a victory that soon may be won. Anna Gyorgy, author of the 1979 "No Nukes" sourcebook, writes from Bonn on Germany's epic shift away from atomic power and toward renewables.

Rare amongst the era's communes, Montague Farm has survived intact. In an evolutionary leap, it became the base for the Zen Peacemaker organization of Roshi Bernie Glassman and Eve Marko. They preserved the land, saved the farmhouse, converted the ancient barn to an astonishing meditation center, and culminated their stay with a landmark gathering on Socially Engaged Buddhism. A new generation of owners is now making the place into a green conference center.

Like Montague Farm, the No Nukes movement still sustains its fair share of diverse opinions. But its commitment to non-violence has deepened, as has its impact on the nuclear industry. Among other things, it's forced open the financial and demand space for an epic expansion of Solartopian technologies--especially solar and wind, which are now significantly cheaper than nukes.

In the wake of that, and of Fukushima, new reactor construction is largely on the ropes in Europe and the US. But President Obama may now nominate a pro-nuclear Secretary of Energy. More than 400 deteriorating reactors still run worldwide, with escalating danger to us all. China, Russia, and South Korea still seem committed to new ones, as does India, where grassroots resistance is fierce.

There's also talk of a new generation of smaller reactors which are unproven, untested, and unlikely to succeed. The decades have taught us that money spent on any form of atomic energy (except for clean-up) means vital resources stripped from the Solartopian technologies we need to survive.

We've also learned that a single act of courage, in concert with a community of dedicated organizers, can change the world. The No Nukes movement continues to succeed with an epic commitment to creative non-violence.

In terms of technology, cost and do-ability, Solartopia is within our grasp. Politically, our ultimate challenge comes with the demand to sustain the daring, wisdom and organic zeal needed to win a green-powered Earth.

For that, we'll do well to remember the sound of one tower crashing.