Reflections of an Anti-War Veteran

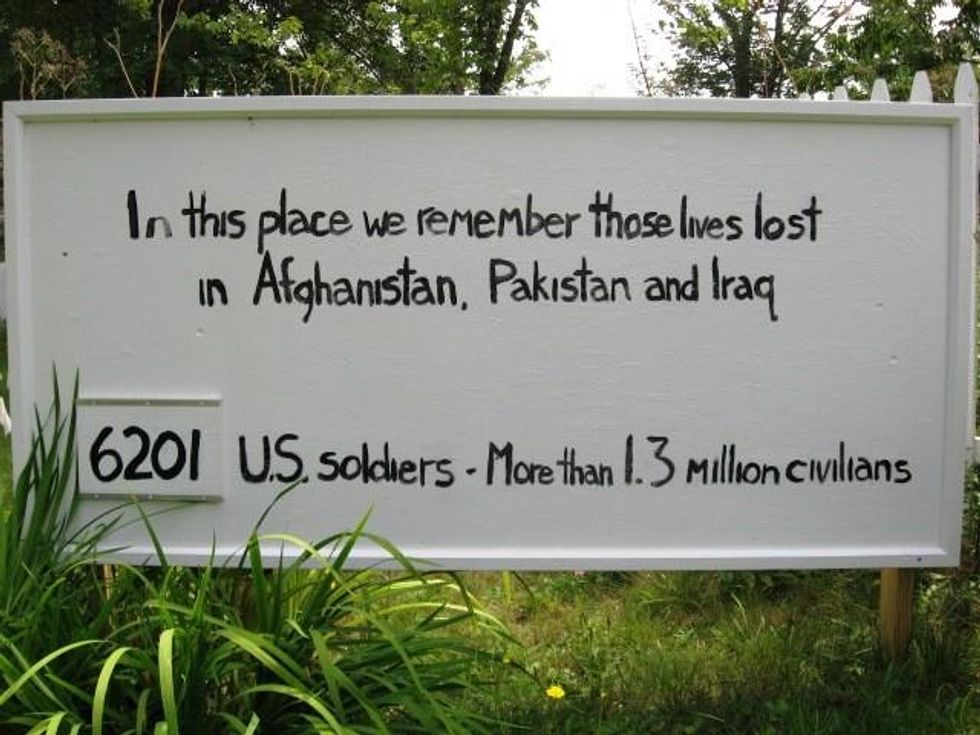

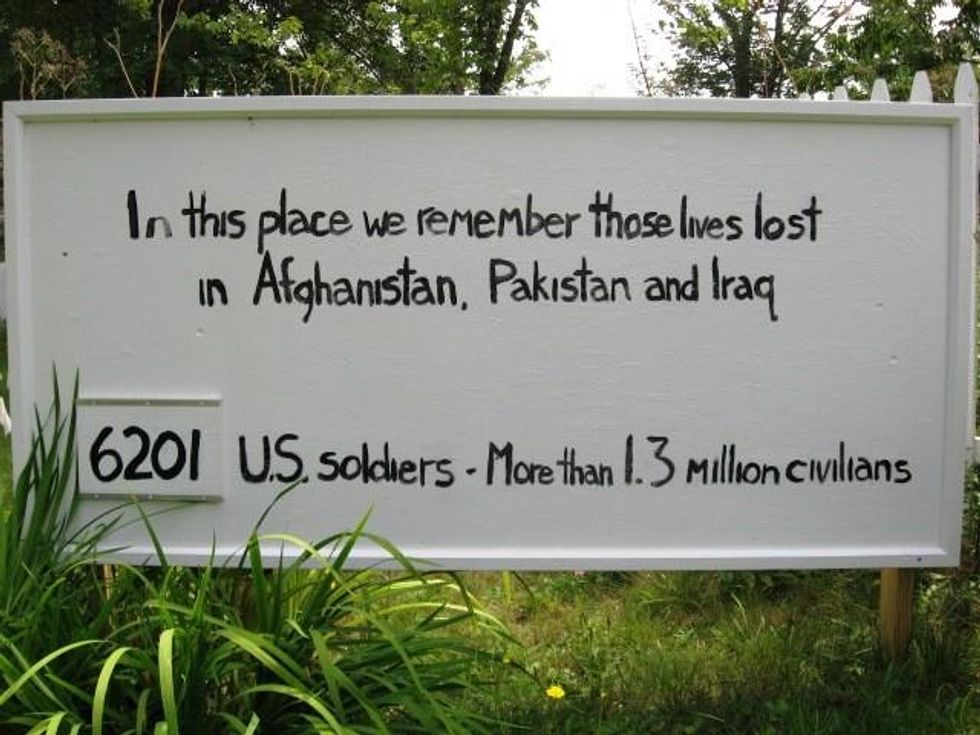

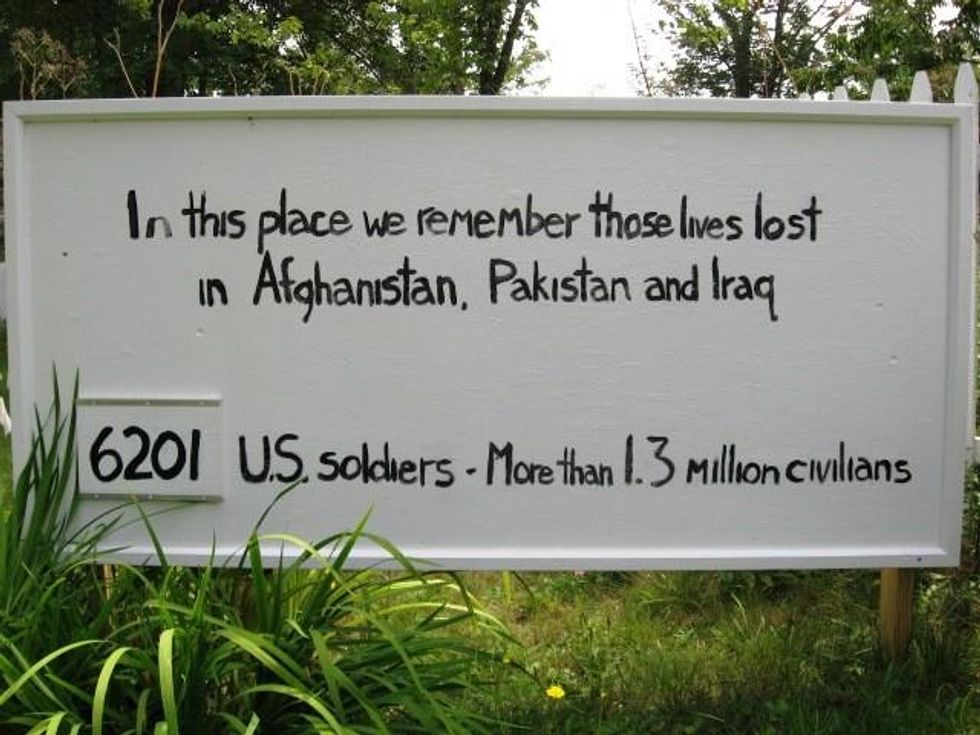

The following remarks were made on the occasion of the removal for winter of flags commemorating lives lost in Iraq and Afghanistan at the Iraq War Dead Memorial in Blue Hill, Maine on Saturday, November 10th, 2012:

I hope to make the case today for us to continue, even redouble, our efforts to effect real change when there may be a window of opportunity for our voices to persuade President Obama to morph into a leader faithful to a gentler inner self.

I have a comforting expectation that my words will fall on sympathetic ears. Not so, if this were your typical Armistice Day parade or gathering happening all over the country this weekend. My remarks don't celebrate or glorify the military, which is what we generally hear on this day. Quite the opposite.

I am extremely proud to be a member of Veterans for Peace. Founded 27 years ago in Maine, VFP now has over 5000 members and more than 130 chapters. We are the only veterans' organization that is opposed to all war and we're dedicated to increasing awareness of the costs of war, to counter-recruiting, and to seeking justice for veterans and all victims of war.

Unfortunately, most Americans would be dismissive of VFP, maintaining we're naive, that man is inherently violent and that, therefore, war is inevitable. My experience teaching peace has convinced me that, on the contrary, there are many cultures that are peaceful and that war is a matter of choice. We here in America resist that notion, I think, largely, because of our violent history. It is simply too uncomfortable for Americans to accept that wars aren't necessary or that war often has been closer to our leaders' first option rather than their last. And so our history only contributes to the disheartening resolute march down a blood-soaked and beaten path.

We Americans need to examine America's record honestly, just as we need to examine the American mythology of exceptionalism. Years ago I came to the conclusion that Martin Luther King, Jr's stinging rebuke on April 4, 1967, was right on. His country was the greatest purveyor of violence. That distinction is inarguably, I think, just as valid today.

Making the case for the U.S. being among the bloodiest of nations prior to WWII meets with considerable resistance, though it's pretty hard to dismiss the genocide of native Americans, the slave trade, our Civil War, the Mexican War, the Spanish American War, when war in the Philippines alone took 300,000 to 500,000 lives, and WWI and II. Could they possibly all be aberrations?

The picture since WWII is too fresh in our memory to deny. Between six and seven million people died in our three big wars since the "good" one--Korea, Vietnam, and Iraq. A total of six to seven million!

Celebrated author and activist Brian Willson's research found that between 1945 and 2008 there have been 390 overt U.S. military interventions. Author William Blum writes that we've bombed 28 countries. When I was teaching I was fond of citing peace guru Colman McCarthy's quiz. He asked his students how many of those incursions led to the establishment of a democratic government respectful of human rights. The answer, sadly and not surprisingly, is zero.

I have recently been reading John Tirman's, "The Deaths of Others", which addresses the question, "Why are Americans so indifferent to the deaths of others?" Tirman is the executive director of the Center for International Studies at MIT and was responsible for the surveys that found that an astonishing 655,000 deaths were attributable to the war in Iraq by 2006. That discovery prompted his investigation into the evident lack of sympathetic response in America to the bloodshed.

In part, Tirman explains, this callousness can be attributed to a conscious campaign by policy makers to assure the American public of the essential rightness of our wars and their benefits to those populations under siege, never mind the horrific death toll.

The selling of war to the American public is, of course, responsible for the victimization of the mostly young people commemorated here. No doubt, many, probably most, believed they were serving an admirable cause--that they were taking freedom and democracy to dark regions of the planet.

These lives lost, along with the physically and emotionally damaged who have returned represent the highest costs of our wars. As an aside: Can we ignore the suicides--nearly one military suicide a day for the first six months of 2012, 26 attempted suicides by active military personnel in July alone? But, the toll is extensive in many other ways we know.

There's the shear monetary drain and the associated "opportunity costs". Costs of our wars since 9/11 will be over $4 trillion. Trillions down a drain that might better have been dedicated to other problems---world poverty, climate change, renewable energy solutions.

Tirman has brought home to me the costs of wars and our militarism as experienced by others and the associated loss of our international stature. Americans may give little attention to our track record--they may be ignorant or oblivious, but citizens of other countries may not be so clueless.

It is well known, for instance, in Iraq and elsewhere in the Middle East that the incidence of abnormal births in Fallujah and Basra is off the charts, though not generally known here. The abnormalities found among the newborn to over half the families recently surveyed in Fallujah are such that we'd rather turn away. Certainly they are an echo of the legacy of Agent Orange in Vietnam where some 2-3 million victims live today, unable to take care of themselves.

In a world connected and informed as it is today, very little is secret. Not these histories in Iraq and Vietnam. Not the torture at the hands of our military, or CIA, or private contractors. Not the renditions, or drone assassinations, or kill lists. Not the crippling sanctions we have imposed on Iran based on totally unsubstantiated claims of a nuclear weapons program. It's all known.

Brian Willson believes that each of those killed at our hands leave behind an average of 5 loved ones who are traumatically conditioned to violence. We should ask what that means and how might those survivors feel about America. A family member of one of our errant drone attacks in Pakistan was quoted as saying, "It is beyond my imagination how they can lack all mercy and compassion, and carry on doing this for years. They are not human beings." We don't want to think about who "they" is.

It is useful to view the consequences of our vast military empire from the perspective of the "other"--through the eyes of the Vietnamese, the Chinese, the Iranians, the Pakistanis. We would have serious objections if the Chinese were to build a base on a Caribbean island as we are doing on the Korean island of Jeju. There would be "push back" if toxic defoliants were sprayed over Miami. And, there would be serious blowback if suddenly Americans were essentially vaporized from above as is happening in Pakistan, and Yemen, and the Sudan, and Mali. And I believe all our bases around the world cause far more mischief than do they make us safe.

So, yes, my experiences in the military and those years since have led me to hate war. For me it is personal. I have sat with and interviewed Inuit from Greenland who were displaced in Trail of Tears-like fashion to make way for Thule Air Force Base. I have sat with and interviewed people of Diego Garcia, a remote Indian Ocean island, who were evicted to make way for a gigantic base from which we have launched bombing missions over Iraq and Afghanistan. I have sat with and interviewed Marshall Islanders whose islands became uninhabitable thanks to our atomic weapons testing there. And I have sat with and interviewed Agent Orange victims and family members in Vietnam. The heart-wrenching stories I have heard, without being overly dramatic, have etched searing images. They are us and we are them and we ought to know their anguish.

For me it is personal. I did not know anyone commemorated here. But, I do know former Marine Jerry Stadtmiller, who was shot in the face in Vietnam and is blind, Duane Wagner who lost both legs to a grenade, Allen Hayes another double leg amputee, victim of a land-mine, Artie Guerrero who was shot four times in Vietnam and is confined to a wheelchair with trauma induced MS, Carlos Moleda, a Navy Seal paraplegic who was shot in Panama, Dan Jensen who lost a leg to a land mine. I knew well my three teammates, nine classmates, and my best friend, Don MacLaughlin whose names are all on the wall. I mourn for them. Just as I mourn the loss of these commemorated here. All victims of failed leadership. All victims of our failure to redirect our government.

Buffy Sainte-Marie has written, "He's the universal soldier. He's fighting for Canada, he's fighting for France and he's fighting for the U.S.A. He's the universal soldier and he really is to blame." But then, she goes on to say, "his orders come from far away no more. They come from here and there and you and me and brothers can't you see. This is not a way to put an end to war." In a youtube video Sainte-Marie says that while composing the song she realized we all must take responsibility--that the soldiers take their orders from the generals, the generals take their orders from the politicians, but the politicians take their orders from us. More like the 1% now; but we can't concede responsibility to them or allow them to prevail.

So I see all those commemorated here to be like you and me. It is right that they be mourned and not forgotten. They are you and me and we all must take responsibility and redouble our awareness and our work to stop what is being done in our names. We must build coalitions, with "occupiers", labor activists, education activists, with health care activists, marriage equality activists, women's rights activists, environmentalists, anti-corporatists, all of us and we must persist and we must know that if not us, then who?

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

The following remarks were made on the occasion of the removal for winter of flags commemorating lives lost in Iraq and Afghanistan at the Iraq War Dead Memorial in Blue Hill, Maine on Saturday, November 10th, 2012:

I hope to make the case today for us to continue, even redouble, our efforts to effect real change when there may be a window of opportunity for our voices to persuade President Obama to morph into a leader faithful to a gentler inner self.

I have a comforting expectation that my words will fall on sympathetic ears. Not so, if this were your typical Armistice Day parade or gathering happening all over the country this weekend. My remarks don't celebrate or glorify the military, which is what we generally hear on this day. Quite the opposite.

I am extremely proud to be a member of Veterans for Peace. Founded 27 years ago in Maine, VFP now has over 5000 members and more than 130 chapters. We are the only veterans' organization that is opposed to all war and we're dedicated to increasing awareness of the costs of war, to counter-recruiting, and to seeking justice for veterans and all victims of war.

Unfortunately, most Americans would be dismissive of VFP, maintaining we're naive, that man is inherently violent and that, therefore, war is inevitable. My experience teaching peace has convinced me that, on the contrary, there are many cultures that are peaceful and that war is a matter of choice. We here in America resist that notion, I think, largely, because of our violent history. It is simply too uncomfortable for Americans to accept that wars aren't necessary or that war often has been closer to our leaders' first option rather than their last. And so our history only contributes to the disheartening resolute march down a blood-soaked and beaten path.

We Americans need to examine America's record honestly, just as we need to examine the American mythology of exceptionalism. Years ago I came to the conclusion that Martin Luther King, Jr's stinging rebuke on April 4, 1967, was right on. His country was the greatest purveyor of violence. That distinction is inarguably, I think, just as valid today.

Making the case for the U.S. being among the bloodiest of nations prior to WWII meets with considerable resistance, though it's pretty hard to dismiss the genocide of native Americans, the slave trade, our Civil War, the Mexican War, the Spanish American War, when war in the Philippines alone took 300,000 to 500,000 lives, and WWI and II. Could they possibly all be aberrations?

The picture since WWII is too fresh in our memory to deny. Between six and seven million people died in our three big wars since the "good" one--Korea, Vietnam, and Iraq. A total of six to seven million!

Celebrated author and activist Brian Willson's research found that between 1945 and 2008 there have been 390 overt U.S. military interventions. Author William Blum writes that we've bombed 28 countries. When I was teaching I was fond of citing peace guru Colman McCarthy's quiz. He asked his students how many of those incursions led to the establishment of a democratic government respectful of human rights. The answer, sadly and not surprisingly, is zero.

I have recently been reading John Tirman's, "The Deaths of Others", which addresses the question, "Why are Americans so indifferent to the deaths of others?" Tirman is the executive director of the Center for International Studies at MIT and was responsible for the surveys that found that an astonishing 655,000 deaths were attributable to the war in Iraq by 2006. That discovery prompted his investigation into the evident lack of sympathetic response in America to the bloodshed.

In part, Tirman explains, this callousness can be attributed to a conscious campaign by policy makers to assure the American public of the essential rightness of our wars and their benefits to those populations under siege, never mind the horrific death toll.

The selling of war to the American public is, of course, responsible for the victimization of the mostly young people commemorated here. No doubt, many, probably most, believed they were serving an admirable cause--that they were taking freedom and democracy to dark regions of the planet.

These lives lost, along with the physically and emotionally damaged who have returned represent the highest costs of our wars. As an aside: Can we ignore the suicides--nearly one military suicide a day for the first six months of 2012, 26 attempted suicides by active military personnel in July alone? But, the toll is extensive in many other ways we know.

There's the shear monetary drain and the associated "opportunity costs". Costs of our wars since 9/11 will be over $4 trillion. Trillions down a drain that might better have been dedicated to other problems---world poverty, climate change, renewable energy solutions.

Tirman has brought home to me the costs of wars and our militarism as experienced by others and the associated loss of our international stature. Americans may give little attention to our track record--they may be ignorant or oblivious, but citizens of other countries may not be so clueless.

It is well known, for instance, in Iraq and elsewhere in the Middle East that the incidence of abnormal births in Fallujah and Basra is off the charts, though not generally known here. The abnormalities found among the newborn to over half the families recently surveyed in Fallujah are such that we'd rather turn away. Certainly they are an echo of the legacy of Agent Orange in Vietnam where some 2-3 million victims live today, unable to take care of themselves.

In a world connected and informed as it is today, very little is secret. Not these histories in Iraq and Vietnam. Not the torture at the hands of our military, or CIA, or private contractors. Not the renditions, or drone assassinations, or kill lists. Not the crippling sanctions we have imposed on Iran based on totally unsubstantiated claims of a nuclear weapons program. It's all known.

Brian Willson believes that each of those killed at our hands leave behind an average of 5 loved ones who are traumatically conditioned to violence. We should ask what that means and how might those survivors feel about America. A family member of one of our errant drone attacks in Pakistan was quoted as saying, "It is beyond my imagination how they can lack all mercy and compassion, and carry on doing this for years. They are not human beings." We don't want to think about who "they" is.

It is useful to view the consequences of our vast military empire from the perspective of the "other"--through the eyes of the Vietnamese, the Chinese, the Iranians, the Pakistanis. We would have serious objections if the Chinese were to build a base on a Caribbean island as we are doing on the Korean island of Jeju. There would be "push back" if toxic defoliants were sprayed over Miami. And, there would be serious blowback if suddenly Americans were essentially vaporized from above as is happening in Pakistan, and Yemen, and the Sudan, and Mali. And I believe all our bases around the world cause far more mischief than do they make us safe.

So, yes, my experiences in the military and those years since have led me to hate war. For me it is personal. I have sat with and interviewed Inuit from Greenland who were displaced in Trail of Tears-like fashion to make way for Thule Air Force Base. I have sat with and interviewed people of Diego Garcia, a remote Indian Ocean island, who were evicted to make way for a gigantic base from which we have launched bombing missions over Iraq and Afghanistan. I have sat with and interviewed Marshall Islanders whose islands became uninhabitable thanks to our atomic weapons testing there. And I have sat with and interviewed Agent Orange victims and family members in Vietnam. The heart-wrenching stories I have heard, without being overly dramatic, have etched searing images. They are us and we are them and we ought to know their anguish.

For me it is personal. I did not know anyone commemorated here. But, I do know former Marine Jerry Stadtmiller, who was shot in the face in Vietnam and is blind, Duane Wagner who lost both legs to a grenade, Allen Hayes another double leg amputee, victim of a land-mine, Artie Guerrero who was shot four times in Vietnam and is confined to a wheelchair with trauma induced MS, Carlos Moleda, a Navy Seal paraplegic who was shot in Panama, Dan Jensen who lost a leg to a land mine. I knew well my three teammates, nine classmates, and my best friend, Don MacLaughlin whose names are all on the wall. I mourn for them. Just as I mourn the loss of these commemorated here. All victims of failed leadership. All victims of our failure to redirect our government.

Buffy Sainte-Marie has written, "He's the universal soldier. He's fighting for Canada, he's fighting for France and he's fighting for the U.S.A. He's the universal soldier and he really is to blame." But then, she goes on to say, "his orders come from far away no more. They come from here and there and you and me and brothers can't you see. This is not a way to put an end to war." In a youtube video Sainte-Marie says that while composing the song she realized we all must take responsibility--that the soldiers take their orders from the generals, the generals take their orders from the politicians, but the politicians take their orders from us. More like the 1% now; but we can't concede responsibility to them or allow them to prevail.

So I see all those commemorated here to be like you and me. It is right that they be mourned and not forgotten. They are you and me and we all must take responsibility and redouble our awareness and our work to stop what is being done in our names. We must build coalitions, with "occupiers", labor activists, education activists, with health care activists, marriage equality activists, women's rights activists, environmentalists, anti-corporatists, all of us and we must persist and we must know that if not us, then who?

The following remarks were made on the occasion of the removal for winter of flags commemorating lives lost in Iraq and Afghanistan at the Iraq War Dead Memorial in Blue Hill, Maine on Saturday, November 10th, 2012:

I hope to make the case today for us to continue, even redouble, our efforts to effect real change when there may be a window of opportunity for our voices to persuade President Obama to morph into a leader faithful to a gentler inner self.

I have a comforting expectation that my words will fall on sympathetic ears. Not so, if this were your typical Armistice Day parade or gathering happening all over the country this weekend. My remarks don't celebrate or glorify the military, which is what we generally hear on this day. Quite the opposite.

I am extremely proud to be a member of Veterans for Peace. Founded 27 years ago in Maine, VFP now has over 5000 members and more than 130 chapters. We are the only veterans' organization that is opposed to all war and we're dedicated to increasing awareness of the costs of war, to counter-recruiting, and to seeking justice for veterans and all victims of war.

Unfortunately, most Americans would be dismissive of VFP, maintaining we're naive, that man is inherently violent and that, therefore, war is inevitable. My experience teaching peace has convinced me that, on the contrary, there are many cultures that are peaceful and that war is a matter of choice. We here in America resist that notion, I think, largely, because of our violent history. It is simply too uncomfortable for Americans to accept that wars aren't necessary or that war often has been closer to our leaders' first option rather than their last. And so our history only contributes to the disheartening resolute march down a blood-soaked and beaten path.

We Americans need to examine America's record honestly, just as we need to examine the American mythology of exceptionalism. Years ago I came to the conclusion that Martin Luther King, Jr's stinging rebuke on April 4, 1967, was right on. His country was the greatest purveyor of violence. That distinction is inarguably, I think, just as valid today.

Making the case for the U.S. being among the bloodiest of nations prior to WWII meets with considerable resistance, though it's pretty hard to dismiss the genocide of native Americans, the slave trade, our Civil War, the Mexican War, the Spanish American War, when war in the Philippines alone took 300,000 to 500,000 lives, and WWI and II. Could they possibly all be aberrations?

The picture since WWII is too fresh in our memory to deny. Between six and seven million people died in our three big wars since the "good" one--Korea, Vietnam, and Iraq. A total of six to seven million!

Celebrated author and activist Brian Willson's research found that between 1945 and 2008 there have been 390 overt U.S. military interventions. Author William Blum writes that we've bombed 28 countries. When I was teaching I was fond of citing peace guru Colman McCarthy's quiz. He asked his students how many of those incursions led to the establishment of a democratic government respectful of human rights. The answer, sadly and not surprisingly, is zero.

I have recently been reading John Tirman's, "The Deaths of Others", which addresses the question, "Why are Americans so indifferent to the deaths of others?" Tirman is the executive director of the Center for International Studies at MIT and was responsible for the surveys that found that an astonishing 655,000 deaths were attributable to the war in Iraq by 2006. That discovery prompted his investigation into the evident lack of sympathetic response in America to the bloodshed.

In part, Tirman explains, this callousness can be attributed to a conscious campaign by policy makers to assure the American public of the essential rightness of our wars and their benefits to those populations under siege, never mind the horrific death toll.

The selling of war to the American public is, of course, responsible for the victimization of the mostly young people commemorated here. No doubt, many, probably most, believed they were serving an admirable cause--that they were taking freedom and democracy to dark regions of the planet.

These lives lost, along with the physically and emotionally damaged who have returned represent the highest costs of our wars. As an aside: Can we ignore the suicides--nearly one military suicide a day for the first six months of 2012, 26 attempted suicides by active military personnel in July alone? But, the toll is extensive in many other ways we know.

There's the shear monetary drain and the associated "opportunity costs". Costs of our wars since 9/11 will be over $4 trillion. Trillions down a drain that might better have been dedicated to other problems---world poverty, climate change, renewable energy solutions.

Tirman has brought home to me the costs of wars and our militarism as experienced by others and the associated loss of our international stature. Americans may give little attention to our track record--they may be ignorant or oblivious, but citizens of other countries may not be so clueless.

It is well known, for instance, in Iraq and elsewhere in the Middle East that the incidence of abnormal births in Fallujah and Basra is off the charts, though not generally known here. The abnormalities found among the newborn to over half the families recently surveyed in Fallujah are such that we'd rather turn away. Certainly they are an echo of the legacy of Agent Orange in Vietnam where some 2-3 million victims live today, unable to take care of themselves.

In a world connected and informed as it is today, very little is secret. Not these histories in Iraq and Vietnam. Not the torture at the hands of our military, or CIA, or private contractors. Not the renditions, or drone assassinations, or kill lists. Not the crippling sanctions we have imposed on Iran based on totally unsubstantiated claims of a nuclear weapons program. It's all known.

Brian Willson believes that each of those killed at our hands leave behind an average of 5 loved ones who are traumatically conditioned to violence. We should ask what that means and how might those survivors feel about America. A family member of one of our errant drone attacks in Pakistan was quoted as saying, "It is beyond my imagination how they can lack all mercy and compassion, and carry on doing this for years. They are not human beings." We don't want to think about who "they" is.

It is useful to view the consequences of our vast military empire from the perspective of the "other"--through the eyes of the Vietnamese, the Chinese, the Iranians, the Pakistanis. We would have serious objections if the Chinese were to build a base on a Caribbean island as we are doing on the Korean island of Jeju. There would be "push back" if toxic defoliants were sprayed over Miami. And, there would be serious blowback if suddenly Americans were essentially vaporized from above as is happening in Pakistan, and Yemen, and the Sudan, and Mali. And I believe all our bases around the world cause far more mischief than do they make us safe.

So, yes, my experiences in the military and those years since have led me to hate war. For me it is personal. I have sat with and interviewed Inuit from Greenland who were displaced in Trail of Tears-like fashion to make way for Thule Air Force Base. I have sat with and interviewed people of Diego Garcia, a remote Indian Ocean island, who were evicted to make way for a gigantic base from which we have launched bombing missions over Iraq and Afghanistan. I have sat with and interviewed Marshall Islanders whose islands became uninhabitable thanks to our atomic weapons testing there. And I have sat with and interviewed Agent Orange victims and family members in Vietnam. The heart-wrenching stories I have heard, without being overly dramatic, have etched searing images. They are us and we are them and we ought to know their anguish.

For me it is personal. I did not know anyone commemorated here. But, I do know former Marine Jerry Stadtmiller, who was shot in the face in Vietnam and is blind, Duane Wagner who lost both legs to a grenade, Allen Hayes another double leg amputee, victim of a land-mine, Artie Guerrero who was shot four times in Vietnam and is confined to a wheelchair with trauma induced MS, Carlos Moleda, a Navy Seal paraplegic who was shot in Panama, Dan Jensen who lost a leg to a land mine. I knew well my three teammates, nine classmates, and my best friend, Don MacLaughlin whose names are all on the wall. I mourn for them. Just as I mourn the loss of these commemorated here. All victims of failed leadership. All victims of our failure to redirect our government.

Buffy Sainte-Marie has written, "He's the universal soldier. He's fighting for Canada, he's fighting for France and he's fighting for the U.S.A. He's the universal soldier and he really is to blame." But then, she goes on to say, "his orders come from far away no more. They come from here and there and you and me and brothers can't you see. This is not a way to put an end to war." In a youtube video Sainte-Marie says that while composing the song she realized we all must take responsibility--that the soldiers take their orders from the generals, the generals take their orders from the politicians, but the politicians take their orders from us. More like the 1% now; but we can't concede responsibility to them or allow them to prevail.

So I see all those commemorated here to be like you and me. It is right that they be mourned and not forgotten. They are you and me and we all must take responsibility and redouble our awareness and our work to stop what is being done in our names. We must build coalitions, with "occupiers", labor activists, education activists, with health care activists, marriage equality activists, women's rights activists, environmentalists, anti-corporatists, all of us and we must persist and we must know that if not us, then who?