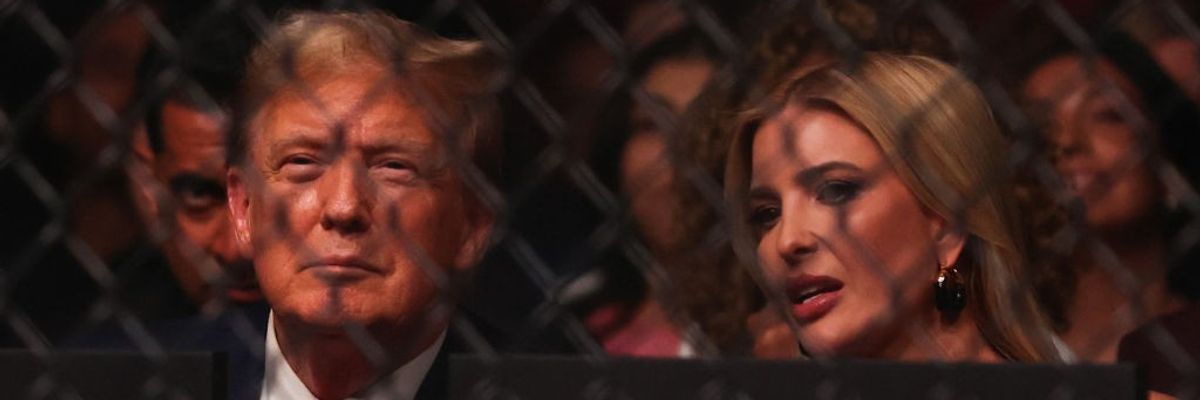

Former U.S. President Donald Trump and Ivanka Trump attend UFC 299 at Kaseya Center on March 9, 2024 in Miami, Florida.

Trump and O.J.: Delusional Psychos in Court Put America on Trial

Just as O.J. became symbolic of the false promise of a color-blind America, so has Trump masqueraded as the champion of Americans underserved by democracy.

It was the jokes about former President Donald Trump’s rumored flatulence in the courtroom that pushed me toward despair. And don’t think it was disgust with the subject matter either. After all, I’ve lived with teenagers and I wasn’t all that surprised by yet another Trump-inspired trivialization of a critical civic institution. What appalled me was the possibility that—let’s be clear here—such stories would somehow humanize the monster, that his alleged farting and possible use of adult diapers would win him sympathy. I even wondered whether such rumors could be part of a scheme to win him votes.

So, yes, Trump can make you that crazy.

Or maybe it’s something about important trials, about the slow unspooling of evidence and our hunger for resolution that makes us simultaneously twitchy and increasingly catatonic. I experienced this once before on a national level, just a little less than 30 years ago, when lawyers for another adored psycho tested the American justice system with what could only be called a sleazy brilliance. They put racism on trial. This time around, democracy may be at stake and it’s possible the defense lawyers may win again (as they just did with another monster, Harvey Weinstein).

Last month, for instance, the Los Angeles Times mistakenly inserted Trump for O.J. in an obituary of the former football star, claiming that the former president had served the former football player’s sentence in prison.

Since the first day of Trump’s trial, I’ve been remembering bits of the O.J. Simpson extravaganza, especially the moment when he was declared not guilty of killing his wife, Nicole Brown Simpson, and her friend Ronald Goldman, outside her condominium in Los Angeles. I recall that moment vividly. I was eating lunch in a Boston sports bar on Tuesday, October 3, 1995, when the verdict was suddenly trumpeted on what seemed like a dozen giant TV sets. The diners, predominantly white, froze in shock. As we sat there, silent, we slowly became aware of a presence surrounding us and then raucous sounds filled the dining room. The kitchen and wait staff, mostly Black, were on the perimeters of that room, clapping and shouting. I was stunned. I had never before witnessed, close up, such irreconcilable factions.

Other Divisions

There certainly have been other examples of the cleaving of America. The Revolution and the Civil War come to mind, not to speak of the half-century-old Boston school-busing controversy and, of course, the insurrection of January 6, 2021. Still, the division over the O.J. decision was so simple, focused, and emotional that it remains for me a dangerous symbol of intransigence. O.J. may have been more representational than real as a national influence, but he was enough of a force to make me wonder what his story presaged and what a verdict in the current trial might provoke in this far shakier time of ours, especially from former president and MAGA goon Donald Trump, a man eager to intimidate those trying him as well as everyone else.

Looking for parallels between Orenthal J. Simpson and Donald J. Trump may produce shaky outcomes, but it could also help sharpen our sense of their symbolic meanings. They were born 13 months apart in the post-World War II boom years. Although Trump was a white, rich New Yorker and O.J. a poor, Black Californian, they were both driven throughout their lives by a desperation to be admired. Both of them were also large men, gabby and good-looking. Their social cunning, however, wore distinctly different masks. Trump is crude in an entitled frat boy way, while O.J. was smooth and ingratiating, particularly with white men (though distinctly rough with women).

In my years as a sports reporter for The New York Times, I dealt with both of them. In one-on-one situations, I always felt I was being played but never threatened. With O.J., it was hard not to be overwhelmed by his neediness to be liked, but I must admit that I was flattered by the attention. With Trump, I knew I was being manipulated by his unctuousness, but he was good copy, too. Early on, it was easy to write Trump off as a buffoon and assume O.J. was a harmless, sweet-natured guy (although the broadcaster Howard Cosell dubbed him “the lost boy”). That either of them might go beyond being an entertainer seemed a silly notion at the time.

The division over the O.J. decision was so simple, focused, and emotional that it remains for me a dangerous symbol of intransigence.

In some ways neither did. For all Trump’s power to energize crowds, it’s never been thanks to an overwhelming idea, an inspiring example, or even an alluring promise. He merely gives his followers permission and justification to enjoy the short-term energy of hate. Eventually, it will undoubtedly turn against him, but not soon enough for the rest of us.

O.J., in contrast, made us feel good, reveling in his phenomenal skill on the football field—he was a beautiful player there and anything but a brute—while taking pleasure in his comedic skills. He was genuinely funny and willing to mock himself. With his 11-year Hall of Fame football career behind him, he began carefully crafting a Hollywood career, avoiding quick-buck blaxpolitation movies for lovable supporting roles. As sportswriter Ralph Wiley put it, white people came to consider Simpson a “unifying symbol of all races.”

The Counter-Revolutionary

O.J. was easy to like, a charming, charismatic, talented athlete and actor who conveniently served to offset much of the growing African-American activism in the world of sports.

The 1968 Olympic demonstrations of John Carlos and Tommie Smith, the hard anger of pro football superstar Jim Brown, the political rants of Muhammad Ali, among others, frightened the owners, broadcasters, and corporate executives who had just gotten a handle on making big money out of sports. O.J. was a welcome counterrevolutionary. And unlike most other Black stars, he was sociable and accessible. It was fun to play golf with him and cavort under his testosterone shower.

When O.J. died last month of prostate cancer at 76, the first image that came to my mind was of that divided Boston sports bar, but it was replaced fairly quickly by images of O.J. himself, iconic ones that shaped our notions of him and of America then, most of them offering a false promise of a color-blind country. Even more memorable than O.J. dancing with the football through whatever defensive line opposed him was O.J. clowning adorably on the movie screen or charging through an airport in a Hertz commercial.

His delusion like Trump’s (until the first of his court cases began recently) was nourished by being treated as if he and he alone could get away with anything.

As for me, I’ll never forget him sitting across a table one night in 1969, the self-defined essence of a figure somehow beyond race in this divided country of ours. That night in Joe Namath’s trendy midtown Manhattan bar, Bachelors III, left me with my basic sense of who that delightful and delusional man was. He was then a 22-year-old former college superstar holding out for more money in his rookie pro-football contract. I was a New York Times sports columnist who had been asked to introduce him to Namath, the recently famous New York Jets Super Bowl quarterback. The introductions had originally been Cosell’s night mission, but as the evening stretched on (and on), it simply got too late for him, and the task fell to me. (I’d been tagging along to cover the first meeting of those two football heroes.)

O.J. on O.J.

Well after midnight in that crowded bar, it became clear that Namath was taking his sweet time in some ritual of celebrity one-upmanship. Before he left, Cosell had offered to drag Namath over, but O.J., ever cool, shook his head. “You don’t rush the great ones,” he said. He started telling me stories to pass the time, ever gracious and clearly fearing I might get bored and leave.

One he told me that night I never forgot—and subsequently retold in the Oscar-winning ESPN documentary “O.J.: Made in America,” directed by Ezra Edelman. It took place at a teammate’s wedding. O.J. overheard a white woman at an adjoining table say, “Look, there’s O.J. Simpson and some [N-words].”

I was appalled. O.J. was amused by my reaction. He said, “No, it was great. Don’t you understand? She knew that I wasn’t Black. She saw me as O.J.”

Now, here’s the quantum O.J. leap: Why do so many people think the 2016 election of Donald Trump was an appropriate response to social and economically wounding decisions imposed by “the elites”?

Other stories followed, though I don’t remember them. All I could think about was how clueless poor O.J. was. He didn’t understand that he was traveling under the protection of an honorary white pass, revocable at any moment. While he could delude himself, I thought, maybe even carry others along in his fantasy, there would undoubtedly be a reckoning someday. Soon enough, Joe Namath did indeed arrive and I was able to slip away, pondering what had already become a disturbing memory, even as O.J. got that rookie football money he demanded and later became a successful movie actor.

His delusion like Trump’s (until the first of his court cases began recently) was nourished by being treated as if he and he alone could get away with anything. (No better example of such a belief was Trump’s 2016 comment that “I could stand in the middle of 5th Avenue and shoot somebody and I wouldn’t lose voters.”) Since his time at the University of Southern California, where he won the Heisman Trophy, college football’s highest award, the police, responding to the domestic violence complaints of his various girlfriends, would rarely stay longer than to collect an autograph. His second wife, Nicole Brown, called for help many times during and after their marriage, sometimes bruised and bleeding. O.J. was arrested once, in 1989, convicted of spousal abuse, and let off with a fine.

If any good came from any of this, including her death, it was the attention that domestic violence finally got.

Paybacks

As to her murder, it’s hard to believe that anyone who paid attention to the evidence brought out in the trial could actually have believed O.J. innocent (though, of course, the jury did exactly that). However, it’s easy to believe someone could think that the not-guilty verdict from a mostly Black jury was payback for all the racist police decisions that had killed so many Black men without any justice in sight. Both Americas expressed in that Boston sports bar could understand that—the only difference being that the exulting kitchen staff might think the payback appropriate, a rare win, while the stunned diners found it morally reprehensible and an implicit threat.

Both Americas might, however, agree on this: the verdict proved that the justice system worked—for anyone with the will and the money to take it all the way.

Now, here’s the quantum O.J. leap: Why do so many people think the 2016 election of Donald Trump was an appropriate response to social and economically wounding decisions imposed by “the elites”? Just as O.J. became symbolic of the false promise of a color-blind America, so has Trump masqueraded as the champion of Americans underserved by democracy, left behind by the exclusionary progress of technology, and likely to be replaced (so he claims) by immigrants of color.

And here’s the big question: What impact will that role of his have on the current Trump jury and, in effect, the 2024 election?

Tackling Trump

Is there any possibility that the Donald Trump chapter in American history is finally ending amid a chorus of farts, done in by a paper-chasing trial that couldn’t be more banal in its particulars? Should it be considered the latest form of ironic payback? After all, O.J. was finally brought down not by beating or even possibly murdering his wife, but by an almost comical armed robbery caper in which he tried to steal back some of his own memorabilia. For that, he would end up serving nine years in prison.

The possibility of a future Trump in prison, the very thought that no one is above the law could in any way apply to him, is, of course, the primary draw of this latest trial of a delusional psycho. Admittedly, it has yet to capture our attention as thoroughly as O.J.’s murder trial did, but it’s still early days in a courtroom where, without live camera and audio coverage, we can’t satisfy our digital-age need for that streaming TV experience. Maybe the fart jokes or some higher level of Trumpian comedy will engage our interest, or perhaps one of his future trials (if they ever take place) will do the trick. It’s hard, of course, for a parade of misdemeanors, including a presidential theft of national security documents, to compete with the memory of a violent murder.

Or maybe, as with so much else in American history, everything will simply start to run together. Last month, for instance, the Los Angeles Times mistakenly inserted Trump for O.J. in an obituary of the former football star, claiming that the former president had served the former football player’s sentence in prison. Republican lawyer and gadfly George Conway commented, “Understandable mistake. It can be hard to keep all these clearly guilty sociopaths straight.”

How true. And now, as we await the first of four possible juries on the former president, hold your nose. Odor in the court.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

It was the jokes about former President Donald Trump’s rumored flatulence in the courtroom that pushed me toward despair. And don’t think it was disgust with the subject matter either. After all, I’ve lived with teenagers and I wasn’t all that surprised by yet another Trump-inspired trivialization of a critical civic institution. What appalled me was the possibility that—let’s be clear here—such stories would somehow humanize the monster, that his alleged farting and possible use of adult diapers would win him sympathy. I even wondered whether such rumors could be part of a scheme to win him votes.

So, yes, Trump can make you that crazy.

Or maybe it’s something about important trials, about the slow unspooling of evidence and our hunger for resolution that makes us simultaneously twitchy and increasingly catatonic. I experienced this once before on a national level, just a little less than 30 years ago, when lawyers for another adored psycho tested the American justice system with what could only be called a sleazy brilliance. They put racism on trial. This time around, democracy may be at stake and it’s possible the defense lawyers may win again (as they just did with another monster, Harvey Weinstein).

Last month, for instance, the Los Angeles Times mistakenly inserted Trump for O.J. in an obituary of the former football star, claiming that the former president had served the former football player’s sentence in prison.

Since the first day of Trump’s trial, I’ve been remembering bits of the O.J. Simpson extravaganza, especially the moment when he was declared not guilty of killing his wife, Nicole Brown Simpson, and her friend Ronald Goldman, outside her condominium in Los Angeles. I recall that moment vividly. I was eating lunch in a Boston sports bar on Tuesday, October 3, 1995, when the verdict was suddenly trumpeted on what seemed like a dozen giant TV sets. The diners, predominantly white, froze in shock. As we sat there, silent, we slowly became aware of a presence surrounding us and then raucous sounds filled the dining room. The kitchen and wait staff, mostly Black, were on the perimeters of that room, clapping and shouting. I was stunned. I had never before witnessed, close up, such irreconcilable factions.

Other Divisions

There certainly have been other examples of the cleaving of America. The Revolution and the Civil War come to mind, not to speak of the half-century-old Boston school-busing controversy and, of course, the insurrection of January 6, 2021. Still, the division over the O.J. decision was so simple, focused, and emotional that it remains for me a dangerous symbol of intransigence. O.J. may have been more representational than real as a national influence, but he was enough of a force to make me wonder what his story presaged and what a verdict in the current trial might provoke in this far shakier time of ours, especially from former president and MAGA goon Donald Trump, a man eager to intimidate those trying him as well as everyone else.

Looking for parallels between Orenthal J. Simpson and Donald J. Trump may produce shaky outcomes, but it could also help sharpen our sense of their symbolic meanings. They were born 13 months apart in the post-World War II boom years. Although Trump was a white, rich New Yorker and O.J. a poor, Black Californian, they were both driven throughout their lives by a desperation to be admired. Both of them were also large men, gabby and good-looking. Their social cunning, however, wore distinctly different masks. Trump is crude in an entitled frat boy way, while O.J. was smooth and ingratiating, particularly with white men (though distinctly rough with women).

In my years as a sports reporter for The New York Times, I dealt with both of them. In one-on-one situations, I always felt I was being played but never threatened. With O.J., it was hard not to be overwhelmed by his neediness to be liked, but I must admit that I was flattered by the attention. With Trump, I knew I was being manipulated by his unctuousness, but he was good copy, too. Early on, it was easy to write Trump off as a buffoon and assume O.J. was a harmless, sweet-natured guy (although the broadcaster Howard Cosell dubbed him “the lost boy”). That either of them might go beyond being an entertainer seemed a silly notion at the time.

The division over the O.J. decision was so simple, focused, and emotional that it remains for me a dangerous symbol of intransigence.

In some ways neither did. For all Trump’s power to energize crowds, it’s never been thanks to an overwhelming idea, an inspiring example, or even an alluring promise. He merely gives his followers permission and justification to enjoy the short-term energy of hate. Eventually, it will undoubtedly turn against him, but not soon enough for the rest of us.

O.J., in contrast, made us feel good, reveling in his phenomenal skill on the football field—he was a beautiful player there and anything but a brute—while taking pleasure in his comedic skills. He was genuinely funny and willing to mock himself. With his 11-year Hall of Fame football career behind him, he began carefully crafting a Hollywood career, avoiding quick-buck blaxpolitation movies for lovable supporting roles. As sportswriter Ralph Wiley put it, white people came to consider Simpson a “unifying symbol of all races.”

The Counter-Revolutionary

O.J. was easy to like, a charming, charismatic, talented athlete and actor who conveniently served to offset much of the growing African-American activism in the world of sports.

The 1968 Olympic demonstrations of John Carlos and Tommie Smith, the hard anger of pro football superstar Jim Brown, the political rants of Muhammad Ali, among others, frightened the owners, broadcasters, and corporate executives who had just gotten a handle on making big money out of sports. O.J. was a welcome counterrevolutionary. And unlike most other Black stars, he was sociable and accessible. It was fun to play golf with him and cavort under his testosterone shower.

When O.J. died last month of prostate cancer at 76, the first image that came to my mind was of that divided Boston sports bar, but it was replaced fairly quickly by images of O.J. himself, iconic ones that shaped our notions of him and of America then, most of them offering a false promise of a color-blind country. Even more memorable than O.J. dancing with the football through whatever defensive line opposed him was O.J. clowning adorably on the movie screen or charging through an airport in a Hertz commercial.

His delusion like Trump’s (until the first of his court cases began recently) was nourished by being treated as if he and he alone could get away with anything.

As for me, I’ll never forget him sitting across a table one night in 1969, the self-defined essence of a figure somehow beyond race in this divided country of ours. That night in Joe Namath’s trendy midtown Manhattan bar, Bachelors III, left me with my basic sense of who that delightful and delusional man was. He was then a 22-year-old former college superstar holding out for more money in his rookie pro-football contract. I was a New York Times sports columnist who had been asked to introduce him to Namath, the recently famous New York Jets Super Bowl quarterback. The introductions had originally been Cosell’s night mission, but as the evening stretched on (and on), it simply got too late for him, and the task fell to me. (I’d been tagging along to cover the first meeting of those two football heroes.)

O.J. on O.J.

Well after midnight in that crowded bar, it became clear that Namath was taking his sweet time in some ritual of celebrity one-upmanship. Before he left, Cosell had offered to drag Namath over, but O.J., ever cool, shook his head. “You don’t rush the great ones,” he said. He started telling me stories to pass the time, ever gracious and clearly fearing I might get bored and leave.

One he told me that night I never forgot—and subsequently retold in the Oscar-winning ESPN documentary “O.J.: Made in America,” directed by Ezra Edelman. It took place at a teammate’s wedding. O.J. overheard a white woman at an adjoining table say, “Look, there’s O.J. Simpson and some [N-words].”

I was appalled. O.J. was amused by my reaction. He said, “No, it was great. Don’t you understand? She knew that I wasn’t Black. She saw me as O.J.”

Now, here’s the quantum O.J. leap: Why do so many people think the 2016 election of Donald Trump was an appropriate response to social and economically wounding decisions imposed by “the elites”?

Other stories followed, though I don’t remember them. All I could think about was how clueless poor O.J. was. He didn’t understand that he was traveling under the protection of an honorary white pass, revocable at any moment. While he could delude himself, I thought, maybe even carry others along in his fantasy, there would undoubtedly be a reckoning someday. Soon enough, Joe Namath did indeed arrive and I was able to slip away, pondering what had already become a disturbing memory, even as O.J. got that rookie football money he demanded and later became a successful movie actor.

His delusion like Trump’s (until the first of his court cases began recently) was nourished by being treated as if he and he alone could get away with anything. (No better example of such a belief was Trump’s 2016 comment that “I could stand in the middle of 5th Avenue and shoot somebody and I wouldn’t lose voters.”) Since his time at the University of Southern California, where he won the Heisman Trophy, college football’s highest award, the police, responding to the domestic violence complaints of his various girlfriends, would rarely stay longer than to collect an autograph. His second wife, Nicole Brown, called for help many times during and after their marriage, sometimes bruised and bleeding. O.J. was arrested once, in 1989, convicted of spousal abuse, and let off with a fine.

If any good came from any of this, including her death, it was the attention that domestic violence finally got.

Paybacks

As to her murder, it’s hard to believe that anyone who paid attention to the evidence brought out in the trial could actually have believed O.J. innocent (though, of course, the jury did exactly that). However, it’s easy to believe someone could think that the not-guilty verdict from a mostly Black jury was payback for all the racist police decisions that had killed so many Black men without any justice in sight. Both Americas expressed in that Boston sports bar could understand that—the only difference being that the exulting kitchen staff might think the payback appropriate, a rare win, while the stunned diners found it morally reprehensible and an implicit threat.

Both Americas might, however, agree on this: the verdict proved that the justice system worked—for anyone with the will and the money to take it all the way.

Now, here’s the quantum O.J. leap: Why do so many people think the 2016 election of Donald Trump was an appropriate response to social and economically wounding decisions imposed by “the elites”? Just as O.J. became symbolic of the false promise of a color-blind America, so has Trump masqueraded as the champion of Americans underserved by democracy, left behind by the exclusionary progress of technology, and likely to be replaced (so he claims) by immigrants of color.

And here’s the big question: What impact will that role of his have on the current Trump jury and, in effect, the 2024 election?

Tackling Trump

Is there any possibility that the Donald Trump chapter in American history is finally ending amid a chorus of farts, done in by a paper-chasing trial that couldn’t be more banal in its particulars? Should it be considered the latest form of ironic payback? After all, O.J. was finally brought down not by beating or even possibly murdering his wife, but by an almost comical armed robbery caper in which he tried to steal back some of his own memorabilia. For that, he would end up serving nine years in prison.

The possibility of a future Trump in prison, the very thought that no one is above the law could in any way apply to him, is, of course, the primary draw of this latest trial of a delusional psycho. Admittedly, it has yet to capture our attention as thoroughly as O.J.’s murder trial did, but it’s still early days in a courtroom where, without live camera and audio coverage, we can’t satisfy our digital-age need for that streaming TV experience. Maybe the fart jokes or some higher level of Trumpian comedy will engage our interest, or perhaps one of his future trials (if they ever take place) will do the trick. It’s hard, of course, for a parade of misdemeanors, including a presidential theft of national security documents, to compete with the memory of a violent murder.

Or maybe, as with so much else in American history, everything will simply start to run together. Last month, for instance, the Los Angeles Times mistakenly inserted Trump for O.J. in an obituary of the former football star, claiming that the former president had served the former football player’s sentence in prison. Republican lawyer and gadfly George Conway commented, “Understandable mistake. It can be hard to keep all these clearly guilty sociopaths straight.”

How true. And now, as we await the first of four possible juries on the former president, hold your nose. Odor in the court.

- Trump Attorneys Mocked for Requesting 2026 Date for January 6 Trial ›

- Listen Live: US Supreme Court Hears Outrageous Argument That Trump Is Above the Law ›

- House Democrats Call for 'Live Broadcasting' of Trump Trial ›

- Win for Trump as US Supreme Court Punts on Immunity Question ›

- Democracy Defenders Stress NY Trump Trial 'Is About Voter Deception' ›

- Judge Fines Trump $9K, Warns of 'Incarceratory Punishment' for Next Gag Order Violation ›

It was the jokes about former President Donald Trump’s rumored flatulence in the courtroom that pushed me toward despair. And don’t think it was disgust with the subject matter either. After all, I’ve lived with teenagers and I wasn’t all that surprised by yet another Trump-inspired trivialization of a critical civic institution. What appalled me was the possibility that—let’s be clear here—such stories would somehow humanize the monster, that his alleged farting and possible use of adult diapers would win him sympathy. I even wondered whether such rumors could be part of a scheme to win him votes.

So, yes, Trump can make you that crazy.

Or maybe it’s something about important trials, about the slow unspooling of evidence and our hunger for resolution that makes us simultaneously twitchy and increasingly catatonic. I experienced this once before on a national level, just a little less than 30 years ago, when lawyers for another adored psycho tested the American justice system with what could only be called a sleazy brilliance. They put racism on trial. This time around, democracy may be at stake and it’s possible the defense lawyers may win again (as they just did with another monster, Harvey Weinstein).

Last month, for instance, the Los Angeles Times mistakenly inserted Trump for O.J. in an obituary of the former football star, claiming that the former president had served the former football player’s sentence in prison.

Since the first day of Trump’s trial, I’ve been remembering bits of the O.J. Simpson extravaganza, especially the moment when he was declared not guilty of killing his wife, Nicole Brown Simpson, and her friend Ronald Goldman, outside her condominium in Los Angeles. I recall that moment vividly. I was eating lunch in a Boston sports bar on Tuesday, October 3, 1995, when the verdict was suddenly trumpeted on what seemed like a dozen giant TV sets. The diners, predominantly white, froze in shock. As we sat there, silent, we slowly became aware of a presence surrounding us and then raucous sounds filled the dining room. The kitchen and wait staff, mostly Black, were on the perimeters of that room, clapping and shouting. I was stunned. I had never before witnessed, close up, such irreconcilable factions.

Other Divisions

There certainly have been other examples of the cleaving of America. The Revolution and the Civil War come to mind, not to speak of the half-century-old Boston school-busing controversy and, of course, the insurrection of January 6, 2021. Still, the division over the O.J. decision was so simple, focused, and emotional that it remains for me a dangerous symbol of intransigence. O.J. may have been more representational than real as a national influence, but he was enough of a force to make me wonder what his story presaged and what a verdict in the current trial might provoke in this far shakier time of ours, especially from former president and MAGA goon Donald Trump, a man eager to intimidate those trying him as well as everyone else.

Looking for parallels between Orenthal J. Simpson and Donald J. Trump may produce shaky outcomes, but it could also help sharpen our sense of their symbolic meanings. They were born 13 months apart in the post-World War II boom years. Although Trump was a white, rich New Yorker and O.J. a poor, Black Californian, they were both driven throughout their lives by a desperation to be admired. Both of them were also large men, gabby and good-looking. Their social cunning, however, wore distinctly different masks. Trump is crude in an entitled frat boy way, while O.J. was smooth and ingratiating, particularly with white men (though distinctly rough with women).

In my years as a sports reporter for The New York Times, I dealt with both of them. In one-on-one situations, I always felt I was being played but never threatened. With O.J., it was hard not to be overwhelmed by his neediness to be liked, but I must admit that I was flattered by the attention. With Trump, I knew I was being manipulated by his unctuousness, but he was good copy, too. Early on, it was easy to write Trump off as a buffoon and assume O.J. was a harmless, sweet-natured guy (although the broadcaster Howard Cosell dubbed him “the lost boy”). That either of them might go beyond being an entertainer seemed a silly notion at the time.

The division over the O.J. decision was so simple, focused, and emotional that it remains for me a dangerous symbol of intransigence.

In some ways neither did. For all Trump’s power to energize crowds, it’s never been thanks to an overwhelming idea, an inspiring example, or even an alluring promise. He merely gives his followers permission and justification to enjoy the short-term energy of hate. Eventually, it will undoubtedly turn against him, but not soon enough for the rest of us.

O.J., in contrast, made us feel good, reveling in his phenomenal skill on the football field—he was a beautiful player there and anything but a brute—while taking pleasure in his comedic skills. He was genuinely funny and willing to mock himself. With his 11-year Hall of Fame football career behind him, he began carefully crafting a Hollywood career, avoiding quick-buck blaxpolitation movies for lovable supporting roles. As sportswriter Ralph Wiley put it, white people came to consider Simpson a “unifying symbol of all races.”

The Counter-Revolutionary

O.J. was easy to like, a charming, charismatic, talented athlete and actor who conveniently served to offset much of the growing African-American activism in the world of sports.

The 1968 Olympic demonstrations of John Carlos and Tommie Smith, the hard anger of pro football superstar Jim Brown, the political rants of Muhammad Ali, among others, frightened the owners, broadcasters, and corporate executives who had just gotten a handle on making big money out of sports. O.J. was a welcome counterrevolutionary. And unlike most other Black stars, he was sociable and accessible. It was fun to play golf with him and cavort under his testosterone shower.

When O.J. died last month of prostate cancer at 76, the first image that came to my mind was of that divided Boston sports bar, but it was replaced fairly quickly by images of O.J. himself, iconic ones that shaped our notions of him and of America then, most of them offering a false promise of a color-blind country. Even more memorable than O.J. dancing with the football through whatever defensive line opposed him was O.J. clowning adorably on the movie screen or charging through an airport in a Hertz commercial.

His delusion like Trump’s (until the first of his court cases began recently) was nourished by being treated as if he and he alone could get away with anything.

As for me, I’ll never forget him sitting across a table one night in 1969, the self-defined essence of a figure somehow beyond race in this divided country of ours. That night in Joe Namath’s trendy midtown Manhattan bar, Bachelors III, left me with my basic sense of who that delightful and delusional man was. He was then a 22-year-old former college superstar holding out for more money in his rookie pro-football contract. I was a New York Times sports columnist who had been asked to introduce him to Namath, the recently famous New York Jets Super Bowl quarterback. The introductions had originally been Cosell’s night mission, but as the evening stretched on (and on), it simply got too late for him, and the task fell to me. (I’d been tagging along to cover the first meeting of those two football heroes.)

O.J. on O.J.

Well after midnight in that crowded bar, it became clear that Namath was taking his sweet time in some ritual of celebrity one-upmanship. Before he left, Cosell had offered to drag Namath over, but O.J., ever cool, shook his head. “You don’t rush the great ones,” he said. He started telling me stories to pass the time, ever gracious and clearly fearing I might get bored and leave.

One he told me that night I never forgot—and subsequently retold in the Oscar-winning ESPN documentary “O.J.: Made in America,” directed by Ezra Edelman. It took place at a teammate’s wedding. O.J. overheard a white woman at an adjoining table say, “Look, there’s O.J. Simpson and some [N-words].”

I was appalled. O.J. was amused by my reaction. He said, “No, it was great. Don’t you understand? She knew that I wasn’t Black. She saw me as O.J.”

Now, here’s the quantum O.J. leap: Why do so many people think the 2016 election of Donald Trump was an appropriate response to social and economically wounding decisions imposed by “the elites”?

Other stories followed, though I don’t remember them. All I could think about was how clueless poor O.J. was. He didn’t understand that he was traveling under the protection of an honorary white pass, revocable at any moment. While he could delude himself, I thought, maybe even carry others along in his fantasy, there would undoubtedly be a reckoning someday. Soon enough, Joe Namath did indeed arrive and I was able to slip away, pondering what had already become a disturbing memory, even as O.J. got that rookie football money he demanded and later became a successful movie actor.

His delusion like Trump’s (until the first of his court cases began recently) was nourished by being treated as if he and he alone could get away with anything. (No better example of such a belief was Trump’s 2016 comment that “I could stand in the middle of 5th Avenue and shoot somebody and I wouldn’t lose voters.”) Since his time at the University of Southern California, where he won the Heisman Trophy, college football’s highest award, the police, responding to the domestic violence complaints of his various girlfriends, would rarely stay longer than to collect an autograph. His second wife, Nicole Brown, called for help many times during and after their marriage, sometimes bruised and bleeding. O.J. was arrested once, in 1989, convicted of spousal abuse, and let off with a fine.

If any good came from any of this, including her death, it was the attention that domestic violence finally got.

Paybacks

As to her murder, it’s hard to believe that anyone who paid attention to the evidence brought out in the trial could actually have believed O.J. innocent (though, of course, the jury did exactly that). However, it’s easy to believe someone could think that the not-guilty verdict from a mostly Black jury was payback for all the racist police decisions that had killed so many Black men without any justice in sight. Both Americas expressed in that Boston sports bar could understand that—the only difference being that the exulting kitchen staff might think the payback appropriate, a rare win, while the stunned diners found it morally reprehensible and an implicit threat.

Both Americas might, however, agree on this: the verdict proved that the justice system worked—for anyone with the will and the money to take it all the way.

Now, here’s the quantum O.J. leap: Why do so many people think the 2016 election of Donald Trump was an appropriate response to social and economically wounding decisions imposed by “the elites”? Just as O.J. became symbolic of the false promise of a color-blind America, so has Trump masqueraded as the champion of Americans underserved by democracy, left behind by the exclusionary progress of technology, and likely to be replaced (so he claims) by immigrants of color.

And here’s the big question: What impact will that role of his have on the current Trump jury and, in effect, the 2024 election?

Tackling Trump

Is there any possibility that the Donald Trump chapter in American history is finally ending amid a chorus of farts, done in by a paper-chasing trial that couldn’t be more banal in its particulars? Should it be considered the latest form of ironic payback? After all, O.J. was finally brought down not by beating or even possibly murdering his wife, but by an almost comical armed robbery caper in which he tried to steal back some of his own memorabilia. For that, he would end up serving nine years in prison.

The possibility of a future Trump in prison, the very thought that no one is above the law could in any way apply to him, is, of course, the primary draw of this latest trial of a delusional psycho. Admittedly, it has yet to capture our attention as thoroughly as O.J.’s murder trial did, but it’s still early days in a courtroom where, without live camera and audio coverage, we can’t satisfy our digital-age need for that streaming TV experience. Maybe the fart jokes or some higher level of Trumpian comedy will engage our interest, or perhaps one of his future trials (if they ever take place) will do the trick. It’s hard, of course, for a parade of misdemeanors, including a presidential theft of national security documents, to compete with the memory of a violent murder.

Or maybe, as with so much else in American history, everything will simply start to run together. Last month, for instance, the Los Angeles Times mistakenly inserted Trump for O.J. in an obituary of the former football star, claiming that the former president had served the former football player’s sentence in prison. Republican lawyer and gadfly George Conway commented, “Understandable mistake. It can be hard to keep all these clearly guilty sociopaths straight.”

How true. And now, as we await the first of four possible juries on the former president, hold your nose. Odor in the court.

- Trump Attorneys Mocked for Requesting 2026 Date for January 6 Trial ›

- Listen Live: US Supreme Court Hears Outrageous Argument That Trump Is Above the Law ›

- House Democrats Call for 'Live Broadcasting' of Trump Trial ›

- Win for Trump as US Supreme Court Punts on Immunity Question ›

- Democracy Defenders Stress NY Trump Trial 'Is About Voter Deception' ›

- Judge Fines Trump $9K, Warns of 'Incarceratory Punishment' for Next Gag Order Violation ›