SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

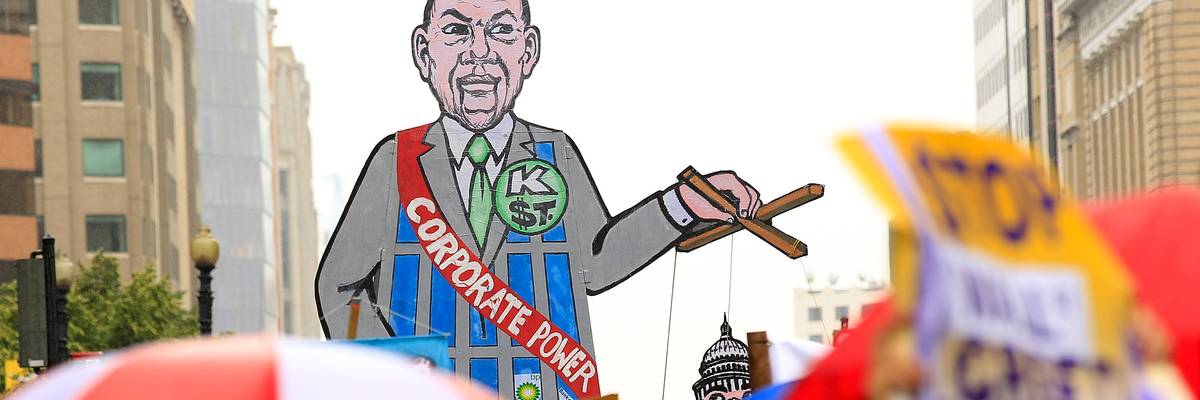

Activists march in a rally to call for Wall Street reform and bank accountability May 17, 2010 in Washington, DC. The march, held by National People's Action, SEIU, the AFL-CIO, and Jobs with Justice, was part of the three-day "Reclaim our Democracy 2010" conference organized by National People's Action.

As philosophers from Socrates to Jesus to Adam Smith have told us over and over: unregulated greed always ends up enriching the few while devastating the rest of society.

The failure of the Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) shows us, once again, that unrestrained greed isn’t good. For even modest greed to have a positive effect in society, it must be regulated.

The CEO of SVB didn’t like the regulations imposed after the 2008 financial meltdown by Congress’ Dodd-Frank legislation, and spent over a half-million dollars bribing…er, influencing…legislators (legalized by 5 Republicans on the Supreme Court) to change the law and exempt his and other smaller, regional banks from what he argued was the heavy hand of government.

While SVB and other smaller banks were generally prosperous and profitable, many wanted to escape from the regulations Congress imposed to protect both depositors and the economy, so they spread some money around Washington DC. Donald Trump then enthusiastically signed the deregulation of smaller banks like SVB into law in 2018.

As Senator Bernie Sanders noted this weekend:

“Let's be clear. The failure of Silicon Valley Bank is a direct result of an absurd 2018 bank deregulation bill signed by Donald Trump that I strongly opposed. Five years ago, the Republican Director of the Congressional Budget Office released a report finding that this legislation would increase the likelihood that a large financial firm with assets of between $100 billion and $250 billion would fail.”

Five years later — predictably — the bank went into receivership and people who’d put their money in its trust were looking at substantial losses while, once again, confidence in the entire system is shaken.

At New York’s First Republic Bank, people were standing in line as the weekend began, suggesting there may be a full-blown run on that bank today. And New York’s Signature Bank was just closed by banking regulators.

The CEO of SVB had pulled millions out just two weeks before, money that Congressman Ro Khanna says should be clawed back and used to make depositors whole:

“There should be a clawback of any of that money,” Khanna told The Washington Post. “It should be going to the depositors.”

Politicians and op-ed writers tight with banksters spent the weekend, of course, demanding government action and bailouts, like in 1987 and 2008. And this morning, President Biden announced he’s going to do it by bending the rules at FDIC. Frankly, he had little choice.

The CEO’s greed didn’t work out well for average taxpayers — who ultimately must backstop the FDIC if this spreads — and bank customers.

These same banksters are the first types of people to tell student loan borrowers that if they can’t repay their debts they need “discipline,” to suck it up, reduce their standard of living, and to “learn the lesson of responsibility.”

But when their own stupid decisions — in this case, investing in largely illiquid long-term bonds — come back to haunt them, they stand before Congress with their hands out.

The era from the 1850s through the 1920s was punctuated by periodic greed-driven bank failures and a lack of federal response to them. One of the biggest of those crashes presaged — some scholars argue, triggered — the Civil War.

Before running for public office Abraham Lincoln was a lawyer in private practice working for the railroads. On August 12, 1857, he was paid $4800 in a check, which he deposited and then converted to cash on August 31. That was fortunate for Lincoln, because just over a month later, in the Great Panic of October 1857, both the bank and the railroad were “forced to suspend payment.”

Of the 66 banks in Illinois, The Central Illinois Gazette (Champagne) reported that by the following April, 27 of them had gone into liquidation. It was a depression so vast that the Chicago Democratic Press declared at its start, the week of Sept. 30, 1857, “The financial pressure now prevailing in the country has no parallel in our business history.”

Unregulated greed wasn’t good back then, either: over 600,000 people died in the Civil War that bank crash contributed to.

Fast forward sixty years.

During the 1920s, according to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), “On average, more than 600 banks failed each year between 1921 and 1929.” In the process, billions of dollars were lost to depositors, mostly farmers, working people, and small businesses who’d been locked out of the big banks and didn’t have the resources to lobby Congress.

To make matters worse, because the Republican administrations of Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover all believed bank regulation was a bad thing that interfered with the greed-driven “invisible hand of the marketplace,” each allowed the trend to continue until the entire system collapsed in the 1929-1933 era.

That was another era, almost 100 years before ours, that proved how unregulated greed could damage our nation and create widespread misery (except among the greedy).

In January and February of 1932, respectively, Congress created the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) and the Glass-Steagall Act, regulating banks to prevent their rich owners from continuing to steal depositors’ cash and then walk away from the banks they’d plundered.

President Franklin Roosevelt, who took office in March of 1933, imposed further stiff regulations on banks and Wall Street, creating the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and putting Joe Kennedy in charge of it.

The late Gloria Swanson, who knew Kennedy well and intensely disliked him (he’d robbed and exploited her), told me over one of our many dinners in her New York apartment back in the 1980s that FDR told her he’d appointed Kennedy because, “It takes a crook to catch a crook.”

And FDR was going after the greedy crooks in a big way.

Between Glass-Steagal and the SEC, banking became a boring if reliably profitable business from the 1930s to the 1980s.

The nation prospered. The middle class grew. The banksters’ greed was hemmed in by FDR’s regulations, then kept there through the administrations of Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, Ford, and Carter. Bank directors and executives did well, but few were buying their own private jets.

Then, President Reagan, as part of his neoliberal “greed is good” agenda, experimented with bank deregulation by lifting many rules governing the operation of Savings and Loan institutions.

They’d been created in 1932 with the Federal Home Loan Act, which heavily regulated the industry and made it functionally subordinate to commercial banks.

But in 1982, Reagan pushed through the Garn-St. Germain Depository Institutions Act, eliminating previous S&L loan-to-value ratios and interest rate caps while killing their main oversight, Regulation Q.

Soon S&Ls were gambling with junk bonds and risky commercial real estate, leading over 1000 of them (almost a third of all S&Ls in the nation) to crash and burn.

Their greedy CEOs and senior executives made off with billions, leaving depositors in the lurch and the Federal government to clean up the mess. Once again, deregulating greed ended up costing the nation hundreds of billions while making a small group of S&L hustlers richer than the pharaohs.

In 1999, Republicans and a few neoliberal Democrats took another run at deregulating banks themselves, spurred into action by a pile of campaign cash made legal by Republicans on the Supreme Court when Lewis Powell wrote the 1978 opinion in First National Bank v Bellotti, writing explicitly that corporations were “persons” entitled to use their “First Amendment-protected free speech” (money) to influence politicians.

Deregulation would both increase bank profits while keeping the banking sector safe, we were told that year, because no banker or stockbroker in his right mind would risk being “embarrassed” by taking such big chances that a misstep could wipe out large sectors of the nation’s economy.

Greed, they told us, was self-regulating. Predictably, it didn’t quite work out that way.

Republican Senator Phil Gramm made that “self-regulating” point on the floor of the Senate in 1999 when selling the end of the 1933 Glass-Steagall law that prevented checkbook banks from using their depositors’ money to gamble in the stock, bond, and real estate markets.

Bought-off legislators fattened their campaign coffers while banksters started gambling and became billionaires. And, of course, it led us straight to the Bush Crash of 2008 when the entire system seized up and you and I bailed out Wall Street with trillions of dollars, hundreds of billions of which the banksters simply pocketed for themselves and their big business buddies as loans and massive bonuses.

Greed paid off for them, although you and I are still paying for it with our taxes via the national debt.

As with so many things, a kernel of truth — in this case about greed and self-interest — has been twisted into a gamed and rigged system by the morbidly rich. They’re quick to quote from the first chapter of Adam Smith’s 1776 classic The Wealth of Nations:

“It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity, but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities, but of their advantages. Nobody but a beggar chooses to depend chiefly upon the benevolence of his fellow-citizens.”

While true, advocates of deregulation completely ignore its corollary, expressed in the second chapter of Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments, in which he argues:

“Man is considered as moral because he is regarded as an accountable being. But an accountable being, as the word expresses, is a being that must give an account of its actions to some other, and that consequently must regulate them according to the good liking of this other.”

When Senators Mike Crapo (R-Idaho) and Joe Manchin (D-WV) pushed their 2018 Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act, dubbed by Elizabeth Warren and others as the Bank Lobbyist Act, many argued it would lead to more bank consolidations (it did) and let smaller banks like SVB take risks that could endanger depositors (they did).

Senator Warren noted on Twitter at the time:

“The #BankLobbyistAct takes 25 of the 40 biggest banks in the country off the watch list for more federal oversight. It weakens consumer protections on mortgages — and makes it harder to fight racial discrimination in housing,” adding that the legislation would “be paving the way for the next big crash.”

Unregulated greed, she predicted, would lead to disastrous outcomes.

And here we are. Whether the failure of the Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) will spark a wider contagion or just be a two-week story illustrating the stupidity of deregulating and trusting billionaire banksters to do the right thing is, as yet, unknown.

But the principle is known. When money, power, or political advantage are at stake, a small number of unscrupulous (sometimes called “sociopathic”) individuals will say or do any and everything they can to game the system for themselves to keep everybody else out.

It may be selling opioids that kill hundreds of thousands of Americans; or poisoning children’s metabolisms with processed, plastic-packaged, forever-chemical-laced “food” that leads to cancer, obesity, and diabetes; or pushing cigarettes or opposing wind and solar farms. There’s always somebody willing to sell their soul for the right price, and somebody else who can afford to pay that price.

We’ve all seen greed working in real time. My father was killed — knowingly — by the asbestos industry and my brother was killed with full knowledge and intention by the tobacco industry. If there’s not such a similar story in your life, you’re an outlier.

And what we all experience on a personal level is amplified a million times when a single greedy person seizes the power to help or destroy millions of lives, like the CEO of a giant employer that is fighting unionization, safety, or environmental regulation.

Often, these are the most high-functioning and well-educated/well-connected sociopaths among us…and the good ones (as in those “good” enough to make billions but only pay 3% income tax) are particularly successful at selling their own personalities: this is the compounding overlay of narcissism.

Donald Trump is its poster child.

Can we stop the sociopaths, the greed-heads, from continuing their destruction of our food supply, our housing stock, and our environment/climate?

It’s a fight, but the greed side literally can mobilize trillions, if necessary. Still, the human and intrinsic love of democracy and fairness mean the outcome is, at this moment, up in the air.

What we do know, however — as philosophers from Socrates to Jesus to Adam Smith have told us over and over — is that unregulated greed always ends up enriching the few while devastating the rest of society.

And, as we learned from the Iroquois and I write about in my next book, The Hidden History of American Democracy, working on behalf of and protecting society from greedy predators should be the first job of every government.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

The failure of the Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) shows us, once again, that unrestrained greed isn’t good. For even modest greed to have a positive effect in society, it must be regulated.

The CEO of SVB didn’t like the regulations imposed after the 2008 financial meltdown by Congress’ Dodd-Frank legislation, and spent over a half-million dollars bribing…er, influencing…legislators (legalized by 5 Republicans on the Supreme Court) to change the law and exempt his and other smaller, regional banks from what he argued was the heavy hand of government.

While SVB and other smaller banks were generally prosperous and profitable, many wanted to escape from the regulations Congress imposed to protect both depositors and the economy, so they spread some money around Washington DC. Donald Trump then enthusiastically signed the deregulation of smaller banks like SVB into law in 2018.

As Senator Bernie Sanders noted this weekend:

“Let's be clear. The failure of Silicon Valley Bank is a direct result of an absurd 2018 bank deregulation bill signed by Donald Trump that I strongly opposed. Five years ago, the Republican Director of the Congressional Budget Office released a report finding that this legislation would increase the likelihood that a large financial firm with assets of between $100 billion and $250 billion would fail.”

Five years later — predictably — the bank went into receivership and people who’d put their money in its trust were looking at substantial losses while, once again, confidence in the entire system is shaken.

At New York’s First Republic Bank, people were standing in line as the weekend began, suggesting there may be a full-blown run on that bank today. And New York’s Signature Bank was just closed by banking regulators.

The CEO of SVB had pulled millions out just two weeks before, money that Congressman Ro Khanna says should be clawed back and used to make depositors whole:

“There should be a clawback of any of that money,” Khanna told The Washington Post. “It should be going to the depositors.”

Politicians and op-ed writers tight with banksters spent the weekend, of course, demanding government action and bailouts, like in 1987 and 2008. And this morning, President Biden announced he’s going to do it by bending the rules at FDIC. Frankly, he had little choice.

The CEO’s greed didn’t work out well for average taxpayers — who ultimately must backstop the FDIC if this spreads — and bank customers.

These same banksters are the first types of people to tell student loan borrowers that if they can’t repay their debts they need “discipline,” to suck it up, reduce their standard of living, and to “learn the lesson of responsibility.”

But when their own stupid decisions — in this case, investing in largely illiquid long-term bonds — come back to haunt them, they stand before Congress with their hands out.

The era from the 1850s through the 1920s was punctuated by periodic greed-driven bank failures and a lack of federal response to them. One of the biggest of those crashes presaged — some scholars argue, triggered — the Civil War.

Before running for public office Abraham Lincoln was a lawyer in private practice working for the railroads. On August 12, 1857, he was paid $4800 in a check, which he deposited and then converted to cash on August 31. That was fortunate for Lincoln, because just over a month later, in the Great Panic of October 1857, both the bank and the railroad were “forced to suspend payment.”

Of the 66 banks in Illinois, The Central Illinois Gazette (Champagne) reported that by the following April, 27 of them had gone into liquidation. It was a depression so vast that the Chicago Democratic Press declared at its start, the week of Sept. 30, 1857, “The financial pressure now prevailing in the country has no parallel in our business history.”

Unregulated greed wasn’t good back then, either: over 600,000 people died in the Civil War that bank crash contributed to.

Fast forward sixty years.

During the 1920s, according to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), “On average, more than 600 banks failed each year between 1921 and 1929.” In the process, billions of dollars were lost to depositors, mostly farmers, working people, and small businesses who’d been locked out of the big banks and didn’t have the resources to lobby Congress.

To make matters worse, because the Republican administrations of Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover all believed bank regulation was a bad thing that interfered with the greed-driven “invisible hand of the marketplace,” each allowed the trend to continue until the entire system collapsed in the 1929-1933 era.

That was another era, almost 100 years before ours, that proved how unregulated greed could damage our nation and create widespread misery (except among the greedy).

In January and February of 1932, respectively, Congress created the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) and the Glass-Steagall Act, regulating banks to prevent their rich owners from continuing to steal depositors’ cash and then walk away from the banks they’d plundered.

President Franklin Roosevelt, who took office in March of 1933, imposed further stiff regulations on banks and Wall Street, creating the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and putting Joe Kennedy in charge of it.

The late Gloria Swanson, who knew Kennedy well and intensely disliked him (he’d robbed and exploited her), told me over one of our many dinners in her New York apartment back in the 1980s that FDR told her he’d appointed Kennedy because, “It takes a crook to catch a crook.”

And FDR was going after the greedy crooks in a big way.

Between Glass-Steagal and the SEC, banking became a boring if reliably profitable business from the 1930s to the 1980s.

The nation prospered. The middle class grew. The banksters’ greed was hemmed in by FDR’s regulations, then kept there through the administrations of Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, Ford, and Carter. Bank directors and executives did well, but few were buying their own private jets.

Then, President Reagan, as part of his neoliberal “greed is good” agenda, experimented with bank deregulation by lifting many rules governing the operation of Savings and Loan institutions.

They’d been created in 1932 with the Federal Home Loan Act, which heavily regulated the industry and made it functionally subordinate to commercial banks.

But in 1982, Reagan pushed through the Garn-St. Germain Depository Institutions Act, eliminating previous S&L loan-to-value ratios and interest rate caps while killing their main oversight, Regulation Q.

Soon S&Ls were gambling with junk bonds and risky commercial real estate, leading over 1000 of them (almost a third of all S&Ls in the nation) to crash and burn.

Their greedy CEOs and senior executives made off with billions, leaving depositors in the lurch and the Federal government to clean up the mess. Once again, deregulating greed ended up costing the nation hundreds of billions while making a small group of S&L hustlers richer than the pharaohs.

In 1999, Republicans and a few neoliberal Democrats took another run at deregulating banks themselves, spurred into action by a pile of campaign cash made legal by Republicans on the Supreme Court when Lewis Powell wrote the 1978 opinion in First National Bank v Bellotti, writing explicitly that corporations were “persons” entitled to use their “First Amendment-protected free speech” (money) to influence politicians.

Deregulation would both increase bank profits while keeping the banking sector safe, we were told that year, because no banker or stockbroker in his right mind would risk being “embarrassed” by taking such big chances that a misstep could wipe out large sectors of the nation’s economy.

Greed, they told us, was self-regulating. Predictably, it didn’t quite work out that way.

Republican Senator Phil Gramm made that “self-regulating” point on the floor of the Senate in 1999 when selling the end of the 1933 Glass-Steagall law that prevented checkbook banks from using their depositors’ money to gamble in the stock, bond, and real estate markets.

Bought-off legislators fattened their campaign coffers while banksters started gambling and became billionaires. And, of course, it led us straight to the Bush Crash of 2008 when the entire system seized up and you and I bailed out Wall Street with trillions of dollars, hundreds of billions of which the banksters simply pocketed for themselves and their big business buddies as loans and massive bonuses.

Greed paid off for them, although you and I are still paying for it with our taxes via the national debt.

As with so many things, a kernel of truth — in this case about greed and self-interest — has been twisted into a gamed and rigged system by the morbidly rich. They’re quick to quote from the first chapter of Adam Smith’s 1776 classic The Wealth of Nations:

“It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity, but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities, but of their advantages. Nobody but a beggar chooses to depend chiefly upon the benevolence of his fellow-citizens.”

While true, advocates of deregulation completely ignore its corollary, expressed in the second chapter of Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments, in which he argues:

“Man is considered as moral because he is regarded as an accountable being. But an accountable being, as the word expresses, is a being that must give an account of its actions to some other, and that consequently must regulate them according to the good liking of this other.”

When Senators Mike Crapo (R-Idaho) and Joe Manchin (D-WV) pushed their 2018 Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act, dubbed by Elizabeth Warren and others as the Bank Lobbyist Act, many argued it would lead to more bank consolidations (it did) and let smaller banks like SVB take risks that could endanger depositors (they did).

Senator Warren noted on Twitter at the time:

“The #BankLobbyistAct takes 25 of the 40 biggest banks in the country off the watch list for more federal oversight. It weakens consumer protections on mortgages — and makes it harder to fight racial discrimination in housing,” adding that the legislation would “be paving the way for the next big crash.”

Unregulated greed, she predicted, would lead to disastrous outcomes.

And here we are. Whether the failure of the Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) will spark a wider contagion or just be a two-week story illustrating the stupidity of deregulating and trusting billionaire banksters to do the right thing is, as yet, unknown.

But the principle is known. When money, power, or political advantage are at stake, a small number of unscrupulous (sometimes called “sociopathic”) individuals will say or do any and everything they can to game the system for themselves to keep everybody else out.

It may be selling opioids that kill hundreds of thousands of Americans; or poisoning children’s metabolisms with processed, plastic-packaged, forever-chemical-laced “food” that leads to cancer, obesity, and diabetes; or pushing cigarettes or opposing wind and solar farms. There’s always somebody willing to sell their soul for the right price, and somebody else who can afford to pay that price.

We’ve all seen greed working in real time. My father was killed — knowingly — by the asbestos industry and my brother was killed with full knowledge and intention by the tobacco industry. If there’s not such a similar story in your life, you’re an outlier.

And what we all experience on a personal level is amplified a million times when a single greedy person seizes the power to help or destroy millions of lives, like the CEO of a giant employer that is fighting unionization, safety, or environmental regulation.

Often, these are the most high-functioning and well-educated/well-connected sociopaths among us…and the good ones (as in those “good” enough to make billions but only pay 3% income tax) are particularly successful at selling their own personalities: this is the compounding overlay of narcissism.

Donald Trump is its poster child.

Can we stop the sociopaths, the greed-heads, from continuing their destruction of our food supply, our housing stock, and our environment/climate?

It’s a fight, but the greed side literally can mobilize trillions, if necessary. Still, the human and intrinsic love of democracy and fairness mean the outcome is, at this moment, up in the air.

What we do know, however — as philosophers from Socrates to Jesus to Adam Smith have told us over and over — is that unregulated greed always ends up enriching the few while devastating the rest of society.

And, as we learned from the Iroquois and I write about in my next book, The Hidden History of American Democracy, working on behalf of and protecting society from greedy predators should be the first job of every government.

The failure of the Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) shows us, once again, that unrestrained greed isn’t good. For even modest greed to have a positive effect in society, it must be regulated.

The CEO of SVB didn’t like the regulations imposed after the 2008 financial meltdown by Congress’ Dodd-Frank legislation, and spent over a half-million dollars bribing…er, influencing…legislators (legalized by 5 Republicans on the Supreme Court) to change the law and exempt his and other smaller, regional banks from what he argued was the heavy hand of government.

While SVB and other smaller banks were generally prosperous and profitable, many wanted to escape from the regulations Congress imposed to protect both depositors and the economy, so they spread some money around Washington DC. Donald Trump then enthusiastically signed the deregulation of smaller banks like SVB into law in 2018.

As Senator Bernie Sanders noted this weekend:

“Let's be clear. The failure of Silicon Valley Bank is a direct result of an absurd 2018 bank deregulation bill signed by Donald Trump that I strongly opposed. Five years ago, the Republican Director of the Congressional Budget Office released a report finding that this legislation would increase the likelihood that a large financial firm with assets of between $100 billion and $250 billion would fail.”

Five years later — predictably — the bank went into receivership and people who’d put their money in its trust were looking at substantial losses while, once again, confidence in the entire system is shaken.

At New York’s First Republic Bank, people were standing in line as the weekend began, suggesting there may be a full-blown run on that bank today. And New York’s Signature Bank was just closed by banking regulators.

The CEO of SVB had pulled millions out just two weeks before, money that Congressman Ro Khanna says should be clawed back and used to make depositors whole:

“There should be a clawback of any of that money,” Khanna told The Washington Post. “It should be going to the depositors.”

Politicians and op-ed writers tight with banksters spent the weekend, of course, demanding government action and bailouts, like in 1987 and 2008. And this morning, President Biden announced he’s going to do it by bending the rules at FDIC. Frankly, he had little choice.

The CEO’s greed didn’t work out well for average taxpayers — who ultimately must backstop the FDIC if this spreads — and bank customers.

These same banksters are the first types of people to tell student loan borrowers that if they can’t repay their debts they need “discipline,” to suck it up, reduce their standard of living, and to “learn the lesson of responsibility.”

But when their own stupid decisions — in this case, investing in largely illiquid long-term bonds — come back to haunt them, they stand before Congress with their hands out.

The era from the 1850s through the 1920s was punctuated by periodic greed-driven bank failures and a lack of federal response to them. One of the biggest of those crashes presaged — some scholars argue, triggered — the Civil War.

Before running for public office Abraham Lincoln was a lawyer in private practice working for the railroads. On August 12, 1857, he was paid $4800 in a check, which he deposited and then converted to cash on August 31. That was fortunate for Lincoln, because just over a month later, in the Great Panic of October 1857, both the bank and the railroad were “forced to suspend payment.”

Of the 66 banks in Illinois, The Central Illinois Gazette (Champagne) reported that by the following April, 27 of them had gone into liquidation. It was a depression so vast that the Chicago Democratic Press declared at its start, the week of Sept. 30, 1857, “The financial pressure now prevailing in the country has no parallel in our business history.”

Unregulated greed wasn’t good back then, either: over 600,000 people died in the Civil War that bank crash contributed to.

Fast forward sixty years.

During the 1920s, according to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), “On average, more than 600 banks failed each year between 1921 and 1929.” In the process, billions of dollars were lost to depositors, mostly farmers, working people, and small businesses who’d been locked out of the big banks and didn’t have the resources to lobby Congress.

To make matters worse, because the Republican administrations of Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover all believed bank regulation was a bad thing that interfered with the greed-driven “invisible hand of the marketplace,” each allowed the trend to continue until the entire system collapsed in the 1929-1933 era.

That was another era, almost 100 years before ours, that proved how unregulated greed could damage our nation and create widespread misery (except among the greedy).

In January and February of 1932, respectively, Congress created the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) and the Glass-Steagall Act, regulating banks to prevent their rich owners from continuing to steal depositors’ cash and then walk away from the banks they’d plundered.

President Franklin Roosevelt, who took office in March of 1933, imposed further stiff regulations on banks and Wall Street, creating the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and putting Joe Kennedy in charge of it.

The late Gloria Swanson, who knew Kennedy well and intensely disliked him (he’d robbed and exploited her), told me over one of our many dinners in her New York apartment back in the 1980s that FDR told her he’d appointed Kennedy because, “It takes a crook to catch a crook.”

And FDR was going after the greedy crooks in a big way.

Between Glass-Steagal and the SEC, banking became a boring if reliably profitable business from the 1930s to the 1980s.

The nation prospered. The middle class grew. The banksters’ greed was hemmed in by FDR’s regulations, then kept there through the administrations of Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, Ford, and Carter. Bank directors and executives did well, but few were buying their own private jets.

Then, President Reagan, as part of his neoliberal “greed is good” agenda, experimented with bank deregulation by lifting many rules governing the operation of Savings and Loan institutions.

They’d been created in 1932 with the Federal Home Loan Act, which heavily regulated the industry and made it functionally subordinate to commercial banks.

But in 1982, Reagan pushed through the Garn-St. Germain Depository Institutions Act, eliminating previous S&L loan-to-value ratios and interest rate caps while killing their main oversight, Regulation Q.

Soon S&Ls were gambling with junk bonds and risky commercial real estate, leading over 1000 of them (almost a third of all S&Ls in the nation) to crash and burn.

Their greedy CEOs and senior executives made off with billions, leaving depositors in the lurch and the Federal government to clean up the mess. Once again, deregulating greed ended up costing the nation hundreds of billions while making a small group of S&L hustlers richer than the pharaohs.

In 1999, Republicans and a few neoliberal Democrats took another run at deregulating banks themselves, spurred into action by a pile of campaign cash made legal by Republicans on the Supreme Court when Lewis Powell wrote the 1978 opinion in First National Bank v Bellotti, writing explicitly that corporations were “persons” entitled to use their “First Amendment-protected free speech” (money) to influence politicians.

Deregulation would both increase bank profits while keeping the banking sector safe, we were told that year, because no banker or stockbroker in his right mind would risk being “embarrassed” by taking such big chances that a misstep could wipe out large sectors of the nation’s economy.

Greed, they told us, was self-regulating. Predictably, it didn’t quite work out that way.

Republican Senator Phil Gramm made that “self-regulating” point on the floor of the Senate in 1999 when selling the end of the 1933 Glass-Steagall law that prevented checkbook banks from using their depositors’ money to gamble in the stock, bond, and real estate markets.

Bought-off legislators fattened their campaign coffers while banksters started gambling and became billionaires. And, of course, it led us straight to the Bush Crash of 2008 when the entire system seized up and you and I bailed out Wall Street with trillions of dollars, hundreds of billions of which the banksters simply pocketed for themselves and their big business buddies as loans and massive bonuses.

Greed paid off for them, although you and I are still paying for it with our taxes via the national debt.

As with so many things, a kernel of truth — in this case about greed and self-interest — has been twisted into a gamed and rigged system by the morbidly rich. They’re quick to quote from the first chapter of Adam Smith’s 1776 classic The Wealth of Nations:

“It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity, but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities, but of their advantages. Nobody but a beggar chooses to depend chiefly upon the benevolence of his fellow-citizens.”

While true, advocates of deregulation completely ignore its corollary, expressed in the second chapter of Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments, in which he argues:

“Man is considered as moral because he is regarded as an accountable being. But an accountable being, as the word expresses, is a being that must give an account of its actions to some other, and that consequently must regulate them according to the good liking of this other.”

When Senators Mike Crapo (R-Idaho) and Joe Manchin (D-WV) pushed their 2018 Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act, dubbed by Elizabeth Warren and others as the Bank Lobbyist Act, many argued it would lead to more bank consolidations (it did) and let smaller banks like SVB take risks that could endanger depositors (they did).

Senator Warren noted on Twitter at the time:

“The #BankLobbyistAct takes 25 of the 40 biggest banks in the country off the watch list for more federal oversight. It weakens consumer protections on mortgages — and makes it harder to fight racial discrimination in housing,” adding that the legislation would “be paving the way for the next big crash.”

Unregulated greed, she predicted, would lead to disastrous outcomes.

And here we are. Whether the failure of the Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) will spark a wider contagion or just be a two-week story illustrating the stupidity of deregulating and trusting billionaire banksters to do the right thing is, as yet, unknown.

But the principle is known. When money, power, or political advantage are at stake, a small number of unscrupulous (sometimes called “sociopathic”) individuals will say or do any and everything they can to game the system for themselves to keep everybody else out.

It may be selling opioids that kill hundreds of thousands of Americans; or poisoning children’s metabolisms with processed, plastic-packaged, forever-chemical-laced “food” that leads to cancer, obesity, and diabetes; or pushing cigarettes or opposing wind and solar farms. There’s always somebody willing to sell their soul for the right price, and somebody else who can afford to pay that price.

We’ve all seen greed working in real time. My father was killed — knowingly — by the asbestos industry and my brother was killed with full knowledge and intention by the tobacco industry. If there’s not such a similar story in your life, you’re an outlier.

And what we all experience on a personal level is amplified a million times when a single greedy person seizes the power to help or destroy millions of lives, like the CEO of a giant employer that is fighting unionization, safety, or environmental regulation.

Often, these are the most high-functioning and well-educated/well-connected sociopaths among us…and the good ones (as in those “good” enough to make billions but only pay 3% income tax) are particularly successful at selling their own personalities: this is the compounding overlay of narcissism.

Donald Trump is its poster child.

Can we stop the sociopaths, the greed-heads, from continuing their destruction of our food supply, our housing stock, and our environment/climate?

It’s a fight, but the greed side literally can mobilize trillions, if necessary. Still, the human and intrinsic love of democracy and fairness mean the outcome is, at this moment, up in the air.

What we do know, however — as philosophers from Socrates to Jesus to Adam Smith have told us over and over — is that unregulated greed always ends up enriching the few while devastating the rest of society.

And, as we learned from the Iroquois and I write about in my next book, The Hidden History of American Democracy, working on behalf of and protecting society from greedy predators should be the first job of every government.