February, 23 2011, 09:12am EDT

US: Lack of Paid Leave Harms Workers, Children

Weak Laws, Discrimination Bad for Families and Business

NEW YORK

Millions of US workers - including parents of infants - are harmed by weak or nonexistent laws on paid leave, breastfeeding accommodation, and discrimination against workers with family responsibilities, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today. Workers face grave health, financial, and career repercussions as a result. US employers miss productivity gains and turnover savings that these cost-effective policies generate in other countries.

The 90-page report, "Failing its Families: Lack of Paid Leave and Work-Family Supports in the US," is based on interviews with 64 parents across the country. It documents the health and financial impact on American workers of having little or no paid family leave after childbirth or adoption, employer reticence to offer breastfeeding support or flexible schedules, and workplace discrimination against new parents, especially mothers. Parents said that having scarce or no paid leave contributed to delaying babies' immunizations, postpartum depression and other health problems, and caused mothers to give up breastfeeding early. Many who took unpaid leave went into debt and some were forced to seek public assistance. Some women said employer bias against working mothers derailed their careers. Same-sex parents were often denied even unpaid leave.

"We can't afford not to guarantee paid family leave under law - especially in these tough economic times," said Janet Walsh, deputy women's rights director at Human Rights Watch and author of the report."The US is actually missing out by failing to ensure that all workers have access to paid family leave. Countries that have these programs show productivity gains, reduced turnover costs, and health care savings."

One woman interviewed by Human Rights Watch said her manager was unhappy about her pregnancy and forced her to clean up the floor and do tasks normally assigned to other staff in the last months of her pregnancy, and refused to let her use accrued paid sick leave after her baby was born. When she returned to work after a six-week unpaid leave, her manager denied her a space to pump breast milk, forced her to work night shifts, and threatened to fire her if she took time off for medical appointments for her ailing baby. Lacking health insurance, she received no treatment for severe post-partum depression.

The federal Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) enables US workers with new children or family members with serious medical conditions to take unpaid job-protected leave, but it covers only about half the workforce. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, only 11 percent of civilian workers (and 3 percent of the lowest-income workers) have paid family leave benefits. Roughly two-thirds of civilian workers have some paid sick leave, but only about a fifth of low-income workers do. Several studies have found that the number of employers voluntarily offering paid family leave is declining.

"Leaving paid leave to the whim of employers means millions of workers are left out, especially low-income workers who may need it most," Walsh said. "Unpaid leave is not a realistic option for many workers who cannot afford it or who risk losing their jobs if they take it."

California and New Jersey are the only two states with public paid family leave insurance programs. Both are financed exclusively through small employee payroll tax contributions. According to a newly released study of the California program conducted by researchers at the Center for Economic and Policy Research and the City University of New York, employers overwhelmingly reported that the program has had a positive or neutral effect on productivity, profitability, turnover, and employee morale. Small businesses were less likely than large ones to report any negative effect. Studies from other countries similarly have found that offering paid leave is good for business, increasing productivity and reducing employee turnover costs.

Moreover, research on the impact of paid maternity leave on health has found that paid and sufficiently long leaves are associated with increased breastfeeding, lower infant mortality, higher rates of immunizations and health visits for babies, and lower risk of postpartum depression.

"Around the world, policymakers understand that helping workers meet their work and family obligations is good public policy," Walsh said. "It's good for business, for the economy, for public health, and for families. It's past time for the US to get on board with this trend."

Other countries - and international treaties - have long recognized the need to provide better support for working families. At least 178 countries have national laws that guarantee paid leave for new mothers, and more than 50 also guarantee paid leave for new fathers. More than 100 countries offer 14 or more weeks of paid leave for new mothers, including Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom. The 34 members of the Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD), among the world's most developed countries, provide on average 18 weeks of paid maternity leave, with an average of 13 weeks at full pay. Additional paid parental leave for fathers and mothers is available in most OECD countries.

In a sign of the importance of paid leave for new parents in other countries, since 2008 and throughout the recession, changes to maternity, paternity, or parental leave benefits in most European Union countries either increased payment benefits or revised the program's structure without lowering benefits, according to a 2010 European Commission report.

Providing paid leave for new parents has not broken the bank in these countries, Human Rights Watch said. For example, public expenditures on maternity leave amount to an average of 0.3 percent of GDP for countries in the European Union and the OECD. Leave benefits are generally financed through public mechanisms, with funds coming from some combination of employee payroll tax deductions, general tax revenue, health insurance funds, and employer contributions. The trend is away from direct employer payment. A 2010 global survey by researchers at McGill and Northeastern Universities showed that countries guaranteeing leave to care for family health have the highest levels of economic competitiveness.

"With relatively minimal expenditures, paid family leave and other work-family supports are literally saving lives, promoting family financial stability, and even increasing business productivity," Walsh said.

The adoption of laws to enable workers to meet work and family obligations around the world has largely been in response to the massive growth in women's participation in the labor force over the past century. Yet in the US, workforce demographic changes have not brought about legal and policy changes to support the modern workforce. In the US, women now constitute roughly half of the workforce, and the vast majority of American children live in households where all adults are working.

In addition to lacking laws on paid family leave in most states, US law is weak in other areas important for working families, Human Rights Watch found. Federal law does provide some support for nursing mothers, but leaves out many workers. There is virtually no protection for workers seeking flexible schedules and little protection against workplace discrimination on the basis of family care-giving responsibilities.

Congress and state legislatures should enact public paid leave insurance for new parents and for workers caring for family members with serious health conditions, Human Rights Watch said. Federal and state governments should expand coverage under laws that support breastfeeding and pumping breast milk at work, promote flexible schedules and work conditions to accommodate family care needs, establish minimum standards for paid sick days, and amend antidiscrimination laws to explicitly prohibit discrimination on the basis of family responsibilities, Human Rights Watch said.

The US should also ratify international treaties that promote equality and decent employment conditions for workers with family responsibilities, including the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW).

"Despite its enthusiasm about 'family values,' the US is decades behind other countries in ensuring the well-being of working families," Walsh said. "Being an outlier is nothing to be proud of in a case like this. We need contemporary policies for contemporary workers."

Profiles of Parents Lacking Work-Family Policy Support

Anita R.

Anita R. works in a veterinary practice that offers no paid maternity leave benefits. After one of her children was born, she took three weeks off, using accrued vacation time. With another, she took four weeks of leave, three unpaid and one with vacation pay. She has no sick leave benefits. Anita's husband had no paid paternity leave and could not take time off when the children were born. When Anita discussed her last pregnancy and leave with her employer, the office manager cut her hours and pay. She filed a pregnancy discrimination claim but dropped it for fear of losing her job. Pumping breast milk at work was difficult. Anita's co-workers seemed horrified at the idea of a pump and were critical of her taking short breaks to express milk. Anita's family fell behind on credit card bills and car payments during her unpaid leave, and money for food was tight.

Diana T.

Diana T. was 18 and worked full-time at a large retail store when her first daughter was born. Her manager was unhappy about her pregnancy and forced Diana to pick up items off the floor late in her pregnancy, even if other staff was available. Diana took a six-week leave without pay when her first daughter was born since her employer did not allow her to use accrued sick pay. When her second daughter was born and she worked for another employer, Diana had a nine-week leave: six paid at 60 percent of her salary (of less than $30,000 per year) and one paid in full through accrued leave. Diana fell into credit card debt and had trouble paying rent during her unpaid leave. She also needed surgery twice shortly after the second birth. She requested, but was denied, a week off to heal and returned to work three days after surgery. Lacking space at work to pump breast milk, Diana breastfed her first baby for 2 months - well short of the 4-to-12 months she had originally planned. Diana had severe post-partum depression after both children, but especially after her first baby, who was ill. Diana's employer regularly threatened to replace her if she took time off for the baby's frequent medical appointments and often switched her to night work, which was especially difficult for her as a single parent. Diana went without health insurance for more than a year and was therefore never treated for her depression.

Samantha B.

When her son was born, Samantha B. worked at a non-profit organization that helped formerly incarcerated people find jobs. She took eight weeks of leave, four paid with accrued vacation and sick leave, and four unpaid. Samantha's husband got two days of paid parental leave, and took two weeks of vacation. Returning to work was difficult. Samantha could not work a late shift due to limited day care center hours, and for several months suffered abdominal pains and could not walk easily due to an infected C-section wound. She was laid off a few months after returning to work and told that her employer needed someone who could work a more flexible schedule. Samantha nursed for three months but stopped shortly after going back to work because there was no private or feasible place to pump. Her employer suggested using a heavily trafficked public restroom with no electric outlets and just two stalls. The unpaid leave took a financial toll. Samantha and her husband - who took on freelance work to supplement his full-time job - went into debt, deferred her student loans, and dipped into savings to pay rent. Her credit cards went into default and she received public assistance for months.

Theresa A.

Theresa A. has three adopted children. She had no leave at all for the first two adoptions because she was not entitled to leave under the Family and Medical Leave Act with one employer, and later could not afford unpaid leave even when entitled to time off under the FMLA. For her first adoption, Theresa returned home with her son from Russia, put him to bed at 5 a.m., and was at work by 11 a.m. With the second, Theresa took half a day off, and her partner had two weeks off. With the third adoption, Theresa's boss allowed her to take 12 weeks off under the FMLA: eight weeks paid through accrued annual leave and four weeks unpaid. Theresa would have taken leave for the first and second adoptions if it had been paid and she had been eligible. Both of her sons had behavior and emotional problems that leave time might have helped address. The first, adopted at 29 months, was behind in skills and had an eating disorder. He was terrified to be away from her, and it took four people at day care to hold him so she could leave each day. Theresa's second child, who had been through 13 foster placements, had severe behavior problems.

Hannah C.

Hannah C. worked close to 38 hours a week in a bank when she became pregnant - just short of full-time. As a result she had no benefits, and did not take a day off during her nine months of pregnancy even though she was ill throughout. Instead, she was assigned the work station closest to the restroom so that she could vomit, freshen up, and come back out. Hannah was not offered paid maternity leave, and she left her job when her son was born. She started caring for other children and doing odd jobs when her baby was about a month old, and struggled for many months to pay for rent and food. She eventually resorted to food stamps.

Human Rights Watch is one of the world's leading independent organizations dedicated to defending and protecting human rights. By focusing international attention where human rights are violated, we give voice to the oppressed and hold oppressors accountable for their crimes. Our rigorous, objective investigations and strategic, targeted advocacy build intense pressure for action and raise the cost of human rights abuse. For 30 years, Human Rights Watch has worked tenaciously to lay the legal and moral groundwork for deep-rooted change and has fought to bring greater justice and security to people around the world.

LATEST NEWS

‘Don't Give the Pentagon $1 Trillion,’ Critics Say as House Passes Record US Military Spending Bill

"From ending the nursing shortage to insuring uninsured children, preventing evictions, and replacing lead pipes, every dollar the Pentagon wastes is a dollar that isn't helping Americans get by," said one group.

Dec 10, 2025

US House lawmakers on Wednesday approved a $900.6 billion military spending bill, prompting critics to highlight ways in which taxpayer funds could be better spent on programs of social uplift instead of perpetual wars.

The lower chamber voted 312-112 in favor of the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for fiscal year 2026, which will fund what President Donald Trump and congressional Republicans call a "peace through strength" national security policy. The proposal now heads for a vote in the Senate, where it is also expected to pass.

Combined with $156 billion in supplemental funding included in the One Big Beautiful Bill signed in July by Trump, the NDAA would push military spending this fiscal year to over $1 trillion—a new record in absolute terms and a relative level unseen since World War II.

The House is about to vote on authorizing $901 billion in military spending, on top of the $156 billion included in the Big Beautiful Bill.70% of global military spending already comes from the US and its major allies.www.stephensemler.com/p/congress-s...

[image or embed]

— Stephen Semler (@stephensemler.bsky.social) December 10, 2025 at 1:16 PM

The Congressional Progressive Caucus (CPC) led opposition to the bill on Capitol Hill, focusing on what lawmakers called misplaced national priorities, as well as Trump's abuse of emergency powers to deploy National Guard troops in Democratic-controlled cities under pretext of fighting crime and unauthorized immigration.

Others sounded the alarm over the Trump administration's apparent march toward a war on Venezuela—which has never attacked the US or any other country in its nearly 200-year history but is rich in oil and is ruled by socialists offering an alternative to American-style capitalism.

"I will always support giving service members what they need to stay safe but that does not mean rubber-stamping bloated budgets or enabling unchecked executive war powers," CPC Deputy Chair Ilhan Omar (D-Minn.) said on social media, explaining her vote against legislation that "pours billions into weapons systems the Pentagon itself has said it does not need."

"It increases funding for defense contractors who profit from global instability and it advances a vision of national security rooted in militarization instead of diplomacy, human rights, or community well-being," Omar continued.

"At a time when families in Minnesota’s 5th District are struggling with rising costs, when our schools and social services remain underfunded, and when the Pentagon continues to evade a clean audit year after year, Congress should be investing in people," she added.

The Congressional Equality Caucus decried the NDAA's inclusion of a provision banning transgender women from full participation in sports programs at US military academies:

The NDAA should invest in our military, not target minority communities for exclusion.While we're grateful that most anti-LGBTQI+ provisions were removed, the GOP kept one anti-trans provision in the final bill—and that's one too many.We're committed to repealing it.

[image or embed]

— Congressional Equality Caucus (@equality.house.gov) December 10, 2025 at 3:03 PM

Advocacy groups also denounced the legislation, with the Institute for Policy Studies' National Priorities Project (NPP) noting that "from ending the nursing shortage to insuring uninsured children, preventing evictions, and replacing lead pipes, every dollar the Pentagon wastes is a dollar that isn't helping Americans get by."

"The last thing Congress should do is deliver $1 trillion into the hands of [Defense] Secretary Pete Hegseth," NPP program director Lindsay Koshgarian said in a statement Wednesday. "Under Secretary Hegseth's leadership, the Pentagon has killed unidentified boaters in the Caribbean, sent the National Guard to occupy peaceful US cities, and driven a destructive and divisive anti-diversity agenda in the military."

Keep ReadingShow Less

Fed Cut Interest Rates But Can't Undo 'Damage Created by Trump's Chaos Economy,' Expert Says

"Working families are heading into the holidays feeling stretched, stressed, and far from jolly."

Dec 10, 2025

A leading economist and key congressional Democrat on Wednesday pointed to the Federal Reserve's benchmark interest rate cut as just the latest evidence of the havoc that President Donald Trump is wreaking on the economy.

The US central bank has a dual mandate to promote price stability and maximum employment. The Federal Open Market Committee may raise the benchmark rate to reduce inflation, or cut it to spur economic growth, including hiring. However, the FOMC is currently contending with a cooling job market and soaring costs.

After the FOMC's two-day monthly meeting, the divided committee announced a quarter-point reduction to 3.5-3.75%. It's the third time the panel has cut the federal funds rate in recent months after a pause during the early part of Trump's second term.

"Today's decision shows that the Trump economy is in a sorry state and that the Federal Reserve is concerned about a weakening job market," House Budget Committee Ranking Member Brendan Boyle (D-Pa.) said in a statement. "On top of a flailing job market, the president's tariffs—his national sales tax—continue to fuel inflation."

"To make matters worse, extreme Republican policies, including Trump's Big Ugly Law, are driving healthcare costs sharply higher," he continued, pointing to the budget package that the president signed in July. "I will keep fighting to lower costs and for an economy that works for every American."

Alex Jacquez, a former Obama administration official who is now chief of policy and advocacy at the Groundwork Collaborative, similarly said that "Trump's reckless handling of the economy has backed the Fed into a corner—stuck between rising costs and a weakening job market, it has no choice but to try and offer what little relief they can to consumers via rate cuts."

"But the Fed cannot undo the damage created by Trump's chaos economy," Jacquez added, "and working families are heading into the holidays feeling stretched, stressed, and far from jolly."

Thanks to the historically long federal government shutdown, the FOMC didn't have typical data—the consumer price index or jobs report—to inform Wednesday's decision. Instead, its new statement and projections "relied on 'available indicators,' which Fed officials have said include their own internal surveys, community contacts, and private data," Reuters reported.

"The most recent official data on unemployment and inflation is for September, and showed the unemployment rate rising to 4.4% from 4.3%, while the Fed's preferred measure of inflation also increased slightly to 2.8% from 2.7%," the news agency noted. "The Fed has a 2% inflation target, but the pace of price increases has risen steadily from 2.3% in April, a fact at least partly attributable to the pass-through of rising import taxes to consumers and a driving force behind the central bank's policy divide."

The lack of government data has also shifted journalists' attention to other sources, including the revelation from global payroll processing firm ADP that the US lost 32,000 jobs in November, as well as Gallup's finding last week that Americans' confidence in the economy has fallen by seven points over the past month and is now at its lowest level in over a year.

The Associated Press highlighted that the rate cut is "good news" for US job-seekers:

"Overall, we've seen a slowing demand for workers with employers not hiring the way they did a couple of years ago," said Cory Stahle, senior economist at the Indeed Hiring Lab. "By lowering the interest rate, you make it a little more financially reasonable for employers to hire additional people. Especially in some areas—like startups, where companies lean pretty heavily on borrowed money—that's the hope here."

Stahle acknowledged that it could take time for the rate cuts to filter down to employers and then to workers, but he said the signal of the reduction is also important.

"Beyond the size of the cut, it tells employers and job-seekers something about the Federal Reserve's priorities and focus. That they're concerned about the labor market and willing to step in and support the labor market. It's an assurance of the reserve's priorities."

The Federal Reserve is now projecting only one rate cut next year. During a Wednesday press conference, Fed Chair Jerome Powell pointed to the three cuts since September and said that "we are well positioned to wait to see how the economy evolves."

However, Powell is on his way out, with his term ending in May, and Trump signaled in a Tuesday interview with Politico that agreeing with immediate interest rate cuts is a litmus test for his next nominee to fill the role.

Trump—who embarked on a nationwide "affordability tour" this week after claiming last week that "the word 'affordability' is a Democrat scam"—also graded the US economy on his watch, giving it an A+++++.

US Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) responded: "Really? 60% of Americans live paycheck to paycheck. 800,000 are homeless. Food prices are at record highs. Wages lag behind inflation. God help us when we have a B+++++ economy."

Keep ReadingShow Less

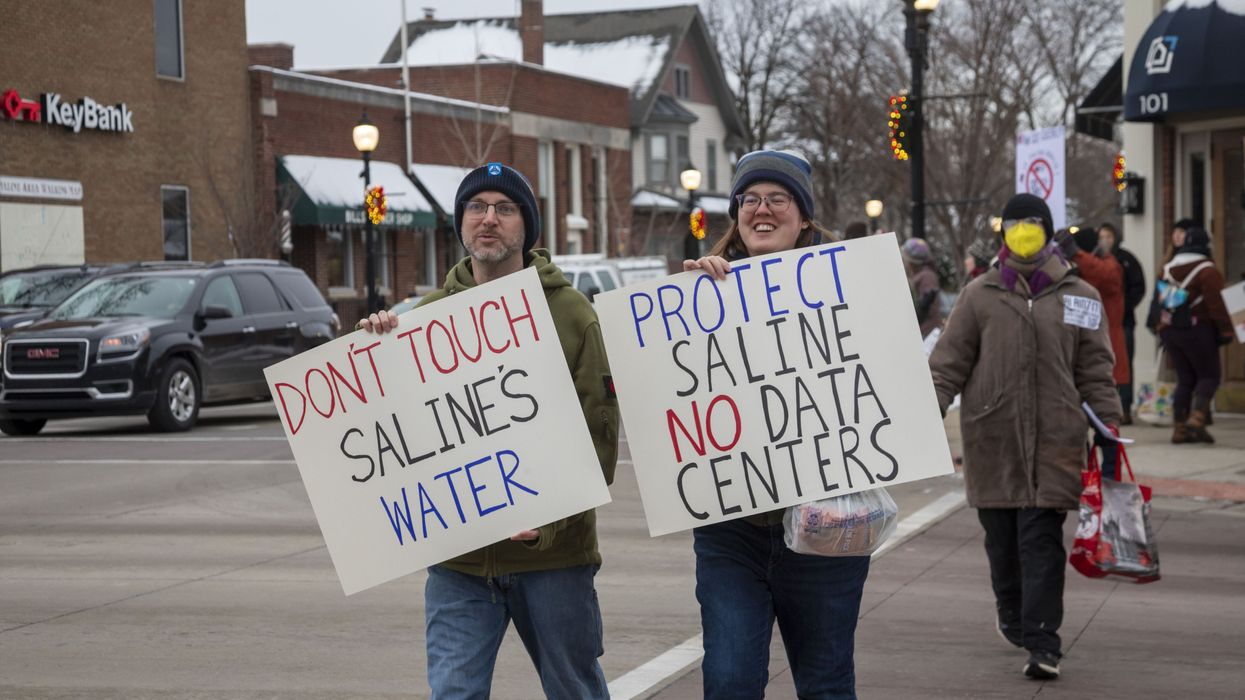

Sanders Champions Those Fighting Back Against Water-Sucking, Energy-Draining, Cost-Boosting Data Centers

Dec 10, 2025

Americans who are resisting the expansion of artificial intelligence data centers in their communities are up against local law enforcement and the Trump administration, which is seeking to compel cities and towns to host the massive facilities without residents' input.

On Wednesday, US Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) urged AI data center opponents to keep up the pressure on local, state, and federal leaders, warning that the rapid expansion of the multi-billion-dollar behemoths in places like northern Virginia, Wisconsin, and Michigan is set to benefit "oligarchs," while working people pay "with higher water and electric bills."

"Americans must fight back against billionaires who put profits over people," said the senator.

In a video posted on the social media platform X, Sanders pointed to two major AI projects—a $165 billion data center being built in Abilene, Texas by OpenAI and Oracle and one being constructed in Louisiana by Meta.

The centers are projected to use as much electricity as 750,000 homes and 1.2 million homes, respectively, and Meta's project will be "the size of Manhattan."

Hundreds gathered in Abilene in October for a "No Kings" protest where one local Democratic political candidate spoke out against "billion-dollar corporations like Oracle" and others "moving into our rural communities."

"They’re exploiting them for all of their resources, and they are creating a surveillance state,” said Riley Rodriguez, a candidate for Texas state Senate District 28.

In Holly Ridge, Lousiana, the construction of the world's largest data center has brought thousands of dump trucks and 18-wheelers driving through town on a daily basis, causing crashes to rise 600% and forcing a local school to shut down its playground due to safety concerns.

And people in communities across the US know the construction of massive data centers are only the beginning of their troubles, as electricity bills have surged this year in areas like northern Virginia, Illinois, and Ohio, which have a high concentration of the facilities.

The centers are also projected to use the same amount of water as 18.5 million homes normally, according to a letter signed by more than 200 environmental justice groups this week.

And in a survey of Pennsylvanians last week, Emerson College found 55% of respondents believed the expansion of AI will decrease the number of jobs available in their current industry. Sanders released an analysis in October showing that corporations including Amazon, Walmart, and UnitedHealth Group are already openly planning to slash jobs by shifting operations to AI.

In his video on Wednesday, Sanders applauded residents who have spoken out against the encroachment of Big Tech firms in their towns and cities.

"In community after community, Americans are fighting back against the data centers being built by some of the largest and most powerful corporations in the world," said Sanders. "They are opposing the destruction of their local environment, soaring electric bills, and the diversion of scarce water supplies."

Keep ReadingShow Less

Most Popular