The equipment was towed across millions of miles of ocean for six decades by marine scientists, meant to collect plankton--but its journeys have also given researchers a treasure trove of data on plastic pollution.

The continuous plankton reporter (CPR) was first deployed in 1931 to analyze the presence of plankton near the surface of the world's oceans. In recent decades, however, its travels have increasingly been disrupted by entanglements with plastic, according to a study published in Nature Communications on Tuesday.

"The message is that marine plastic has increased significantly and we are seeing it all over the world, even in places where you would not want to, like the Northwest Passage and other parts of the Arctic," Clare Ostle, a researcher at the Marine Biological Association in Plymouth, England, told the Guardian.

The CPR originated in northern England and has been continuously towed by boats across more than 6.5 million miles of ocean for more than 60 years.

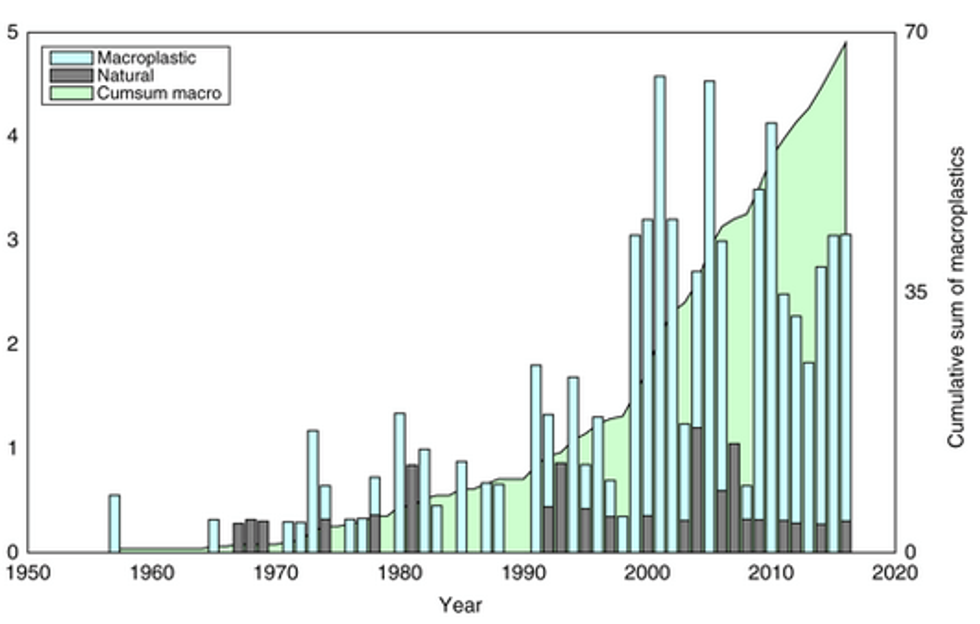

It was first disrupted by plastic entanglement in 1957, when a fishing line got in its way. Eight years later the CPR ran into a plastic bag. The disruptions became increasingly common in the following years.

By the 1990s, two percent of the CPR's missions were disrupted by plastic pollution--mainly discarded nets and other fishing equipment, as well as other plastic products.

The rate of disruption is now between three and four percent, according to scientists at the Marine Biological Association and the University of Plymouth, who compiled the research.

The CPR is pulled by boats at a depth of about 22 feet (7 meters) below the ocean surface, where many marine creatures live--confirming earlier studies which have found that marine life has been increasingly threatened by plastic pollution.

"The realization that plastics are ubiquitous, and that the consequent health impacts are yet to be fully understood, has increased the awareness surrounding plastics," the report reads. "There is a need for re-education, continued research, and awareness campaigns, in order to drive action from the individual as well as large-scale decisions on waste-management and product design."

"The dataset presented here," the authors said, "is an important historical record for the continued monitoring of plastics in the ocean, and confirms the importance of actions to reduce and improve plastic waste."