Corporate media are typically loath to cover protests (at least, those not of the right-wing variety), as years of FAIR analysis can attest. But the remarkable ongoing nationwide protests against racism and police brutality have not only drawn widespread media coverage, they've shifted the national conversation on public safety.

In the little more than two weeks since George Floyd's brutal death at the hands of Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin, the idea of defunding the police was mentioned on the nation's TV networks and in its national newspapers at least 300 times. In the entire year preceding that, it was mentioned exactly twice (Washington Post, 1/10/20; CNN, 6/22/19)--both times using the specter of police defunding as a political weapon, and completely disconnected from any activism advocating for it.

Today, nearly every major outlet has published an article attempting to explain what "defund the police" means--and most are treating the call with seriousness rather than derision. This remarkable shift comes as media outlets have become increasingly critical of the widespread violence by police departments across the country against nonviolent protesters, and against journalists themselves (FAIR.org, 6/9/20). This reporting on protester demands is a welcome change, and a testament to the power of nonviolent popular uprising.

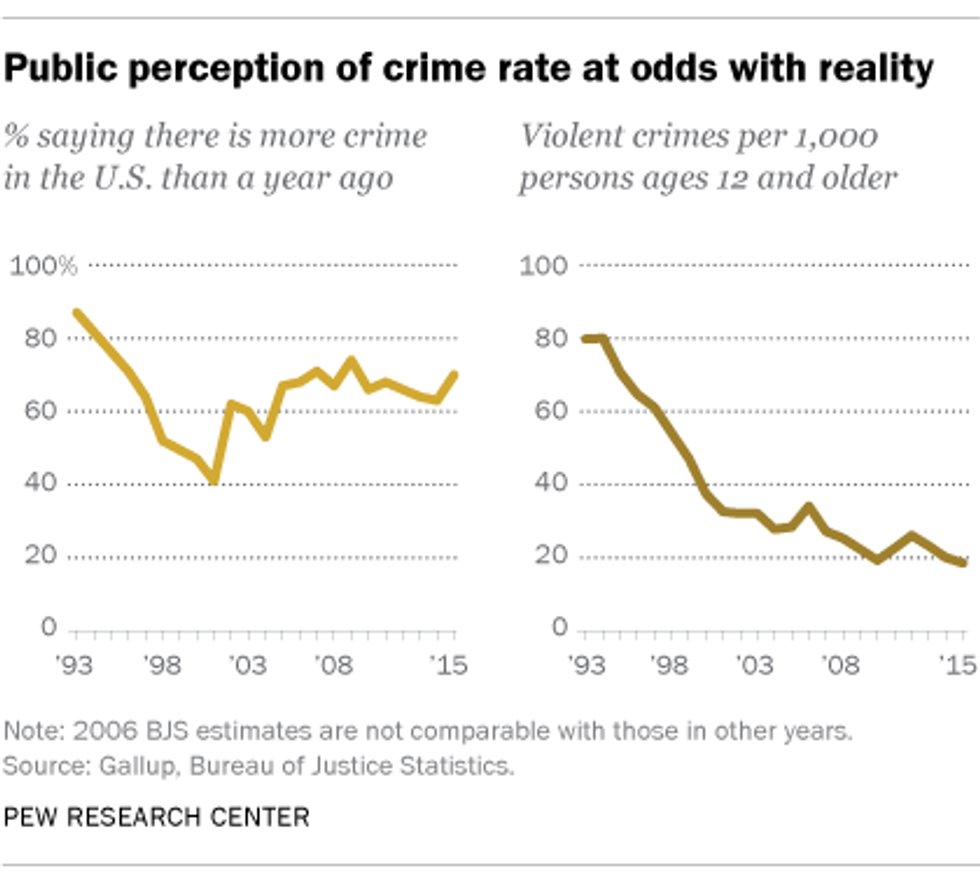

It's important to remember that media have been complicit in the steady increase in police budgets over the years. While violent crime has dropped dramatically since the early 1990s, people have consistently reported for the past 20 years that they believe it is increasing. (See Gallup and Pew research.) Media have played no small role in those misperceptions. The New York Times, for example, mentioned "homicide" or "murder" in 129 headlines in 1990, when the city's murder rate was 31 per 100,000. In 2013, when the rate had plummeted to 4 per 100,000, it ran more murder headlines--135 (HuffPost, 3/16/15).

And newspapers have long been cheerleaders for expanded policing, like the discredited "broken windows" strategy of ramping up policing of low-level offenses in the hopes of having an impact on violent crimes (FAIR.org, 7/3/16). As Josmar Trujillo has pointed out (FAIR.org, 2/12/16), in the wake of the 2014 protests over the police killings of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and Eric Garner in New York City, reporters and pundits steered the national conversation on police reform toward the idea of "community policing"--a term as agreeable-sounding as it is vague, and which in practice typically means more police, and more reliance on police for community problem-solving--exactly the opposite of what protesters were (and still are) calling for.

Today, even as ideas for police reform that barely surfaced in corporate media in the past are becoming part of the mainstream conversation, media continue to try to steer that conversation away from its radical edge.

First, the remarkable: The Washington Post editorial board (6/9/20)--not known for its friendliness to revolutionary ideas--called the "provocative slogan...a welcome call to reimagine public safety in the United States." The editorial asked whether police really ought to be responding to mental health emergencies, dealing with homelessness, and funding local governments by "extracting fees from citizens," and opined that "onlookers are rightfully alarmed at plans to slash social services while sparing police budgets."

The Los Angeles Times editorial board (6/8/20), which, as it openly acknowledged, "has consistently backed the expansion of the LAPD," argued that the city government's proposed 8% cut to the police budget should be "the beginning of a larger rethinking of the mission and scope of the LAPD," and that the city should stop "treating the LAPD as the answer to all public safety problems." At the same time, the paper clearly attempted to stake out limits on the debate, dismissing local organizations' call for a 90% police budget cut--with the funds redirected to community services and investment--as "extreme."

At the Baltimore Sun, the editorial board (6/8/20) weighed in with ambivalent support that served to defang protester demands. "Defund the Police: Not as Scary (or New) as It Sounds," read the headline, under which the board explained:

Here in Baltimore where the post-Freddie Gray police reform efforts have barely taken root, there's an urgency to addressing police misconduct and criminal justice disparities (as well as broader societal inequities that transcend policing) but not necessarily to fundamentally changing course.

They concluded: "This much is clear: Defunding is not an anarchist's plot so much as a continuation of reform efforts, many of which have proven effective."

Editorial support for protester demands, however tepid, was hardly uniform. The ever-reliably right-wing Wall Street Journal editorial board (6/8/20), for instance, held fast to fear-mongering under the headline, "Defund Police, Watch Crime Return," and many big local papers likewise pushed back against calls for police budget cuts (e.g., Chicago Tribune, 6/10/20; San Francisco Chronicle, 6/9/20; St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 6/8/20).

There are plenty of other examples of journalists and pundits throwing cold water on protester demands. Under the headline, "Protesters Hope This Is a Moment of Reckoning for American Policing. Experts Say Not So Fast," Washington Post reporters (6/7/20) warned hopeful protesters that "Floyd's killing might not be the watershed moment that civil rights advocates are hoping for."

Elsewhere in the Post (6/7/20), a team of reporters describing the defund police movement framed the dilemma facing politicians:

Officials face a politically fraught decision about how to respond, weighing whether to stand with protesters who are demanding an extreme overhaul at the risk of jeopardizing public safety and taking authority away from police officers in communities that have sought more protection against violent crime.

So to "stand with protesters" means "jeopardizing public safety"--thanks for clarifying, Washington Post!

But this pat framing contradicts some of its own sources, who attempted to explain that calls for defunding the police are not calls for abandonment of public safety, but rather reinvesting in resources that will enhance public safety without the threat or use of force--and not such that "someone just flips a switch and there are no police," in the quoted words of sociologist Alex Vitale, but over time.

It also quoted Minneapolis City Council president Lisa Bender, who explained the majority's decision to disband the city's police department:

It's our commitment to end policing as we know it, and re-create systems of public safety that actually keep us safe.... Our efforts at incremental reform have failed. Period.

The paper countered these views with several law enforcement voices, like acting Homeland Security Secretary Chad Wolf, who called the idea of defunding police "an absurd assertion"--and it's those voices that come through in the paper's "neutral" reporting voice.

Further down, the reporters wrote:

Though a popular rallying cry at a tense moment, defunding police departments is not always what residents really want, and the issue of just how many officers to put in neighborhoods is complex, particularly in areas with high rates of crime.

As evidence of what residents "really want," the paper pointed to a forum in Washington, DC, about

how to ensure children and teenagers have safe routes to and from school after students were killed on their commutes. Students said they wanted more officers to patrol their routes, but they also said they hated walking out of their school buildings in the afternoon and seeing police cars parked outside.

That's the whole point: what people "really want" is safety from violence, but for many, the sources of that violence include the police. When increased policing has always been the only solution given serious discussion in media, most people have had no way to even have a conversation about how to keep safe without having to rely primarily on a force trained in the use of militarized, violent tactics--which leaves them with seemingly contradictory and impossible responses to questions of public safety.

CNN's Chris Cillizza (6/8/20) devoted a recent column to the rhetorical question, "Is 'Defund the Police' a Massive Political Mistake?" Cillizza's main evidence is a series of tweets by Donald Trump about the "Radical Left" and "Law & Order," and his campaign's farcical attempts to link Joe "Shoot 'Em in the Leg" Biden to the Defund Police movement.

The "heart of the problem," Cillizza argued, is that while "it is likely that what most people involved in these protests want is not to take all money away from police departments and get rid of cops," but rather "an examination of the budgets for police departments and a look at the increased militarization of local law enforcement," Trump will destroy the nuance of that call.

In fact, "defund the police" means different things to different people saying it, but for nearly all of them it means much more than "looks" and "examinations." They point out that reform has been tried in many places--including Minneapolis, where Floyd was killed--to no effect, which is why alternatives to policing are needed.

But after watering down their demands, Cillizza's solution to the problem he laid out isn't using the power of journalism to make sure the conversation doesn't succumb to Trump's efforts. Instead, he advocated for politicians to likewise water down calls for deep, systemic change:

Democratic leaders need to change the conversation to be about reforming police departments and re-allocating some resources for more community building and less militarization.

By asking protesters to be less bold, to not overreach, Cillizza adheres to one of corporate media's most important roles: placing limits on the acceptable and the possible.

Many of those calling to defund the police do mean exactly that. While nearly every outlet has been quick to ridicule the idea of defunding the police entirely as ridiculous--parroting the message coming from police themselves--police abolitionists are indeed pushing people to envision a world where police (and prisons) as we know them are obsolete.

Taking away 90% of the LAPD's budget, as local activists have demanded, is essentially police abolition. As Mohamed Shehk of the abolitionist organization Critical Resistance argues:

Those in power work very hard to make us believe that imprisonment and policing are natural, but we know the opposite to be true. These systems had to be put in place, and must be constantly reinforced and legitimized to the point that we are made to believe that our society will descend into chaos if they don't exist. In reality, the prison industrial complex is responsible for the chaos that many people experience through separation, destabilization and state violence, especially in Black, Indigenous and communities of color.

Communities past and present have long used practices of resolving harm and conflict without relying on punitive measures, like caging or policing. There are many communities today who by default address conflict themselves because they simply don't trust the police--for good reason. More and more people have been exploring and practicing restorative and transformative justice models to hold people accountable for harm committed, many of which are inspired by Indigenous and non-Western practices and values. Harm and conflict predate cops and cages, will outlive them, and communities ultimately will continue to have creative ways of addressing and overcoming them.

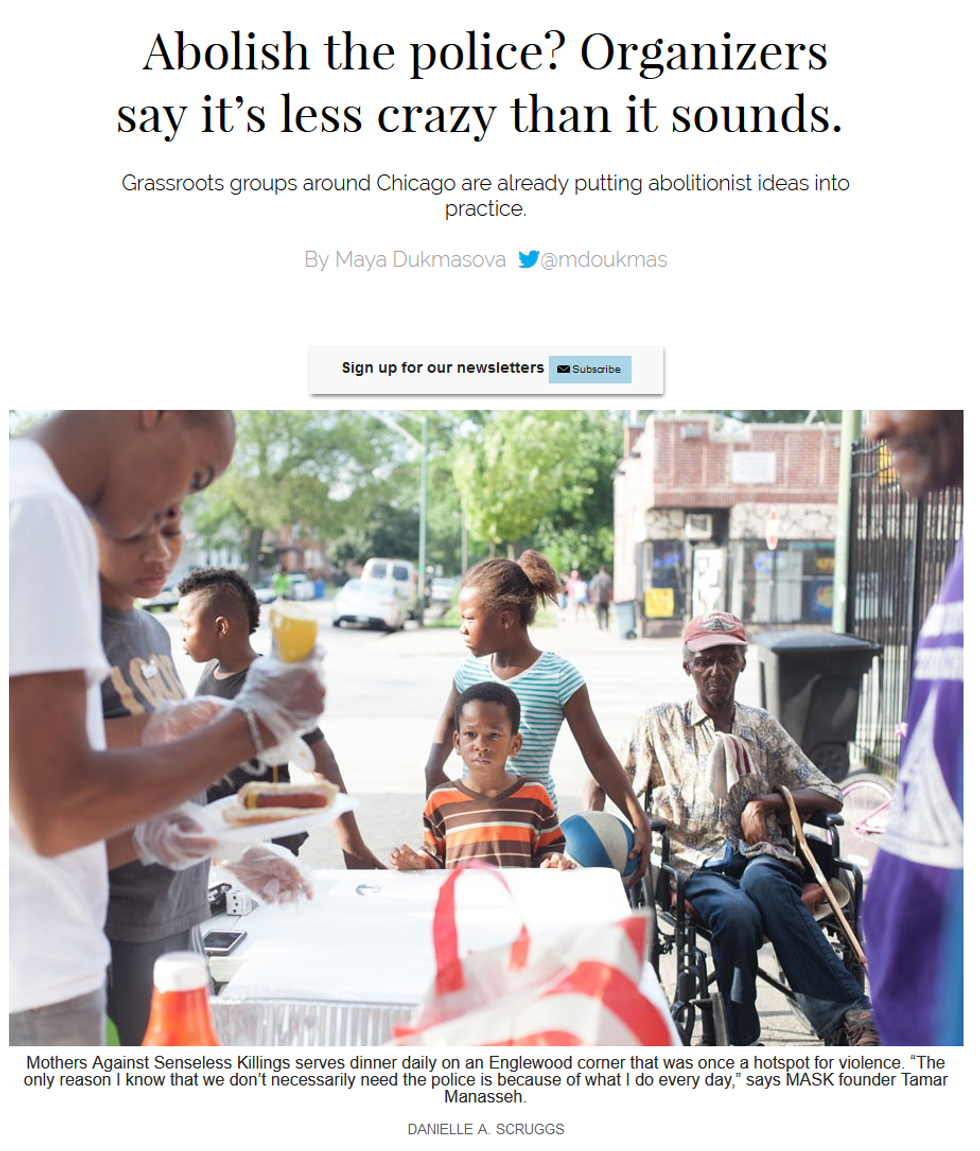

In a lengthy exploration of police abolition in the independent Chicago Reader (8/25/16), activist Mariame Kaba explains to reporter Maya Dukmasova that the abolitionist project is not just about police, but the whole prison industrial complex, and that it requires rethinking entire systems of crime, punishment, property and social relations: "Abolition is not about changing one thing. It's about changing everything, together."

Media wave away this possibility as absurd, but how to move beyond the US's racist, shockingly violent criminal justice system is a discussion our country not only can but desperately needs to have.