SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

New York Times depiction (1/25/20) of a wet market in Shenzhen, which is 680 miles from Wuhan. (Photo: Lam Yik Fei/New York Times)

The stigmatization of Asian people and their culture as "inferior" or "exotic" isn't a new phenomenon. What is considered acceptable or "strange" meat is often the result of arbitrary cultural norms, and Chinese food has often suffered from hypocritical cultural appropriation once it became popular, before being stigmatized again by racist and propagandistic news coverage following the Covid-19 outbreak (FAIR.org, 3/6/20, 3/24/20). Alongside a spike in hate crimes against Asian people are reports of Asian restaurants and other businesses--especially those owned and run by Chinese people--struggling to survive because of resurging racist stereotypes about "dirty" Chinese eating habits.

As James Palmer noted in Foreign Policy (1/27/20), debunking a widely circulated video of a supposed ordinary Chinese woman in Wuhan biting into a whole bat (the featured woman was the host of an online travel show, eating in the Micronesian nation of Palau), Americans have long branded Chinese people as carriers of disease. For example, in 1854, the New York Tribune wrote that Chinese people were "uncivilized, unclean, filthy beyond all conception."

And if there's a reason why it's widely believed that the novel coronavirus emerged in a Chinese "wet market" in Wuhan, it's because many of the earliest reports treated this origin theory as fact.

The South China Morning Post (1/22/20) reported that "exotic animals" were "available at a wet market in the central Chinese city of Wuhan that is ground zero of a new virus," with many of those infected having lived or worked near the Huanan Wholesale Seafood Market, which experts "believe is the source of the virus." The New York Times' "China's Omnivorous Markets Are in the Eye of a Lethal Outbreak Once Again" (1/25/20) reported that "the markets are fixtures in scores of Chinese cities," and "they are the source of an epidemic." The Wall Street Journal (1/26/20) reported that the "carcasses and live specimens" found in the Huanan Market are "typical of the wet markets where most people in this country buy their food," making China a "hot spot for such outbreaks," with its "long tradition of eating wildlife."

While the possibility of Covid-19 emerging from these so-called "wet markets" hasn't been eliminated, it is not at all certain that the virus emerged from these markets. When CNN (4/6/20) interviewed several virus experts for a report on the various origin theories of Covid-19, all of them acknowledged that anyone who claims to know the origins of the outbreak with certainty is "guessing," with the experts reportedly "at odds" over the "once widely accepted theory that the virus originated at a wet market."

New information is constantly being updated, and while scientists currently seem confident that the virus initially spilled over from bats, because they're considered to be natural hosts of coronaviruses, the intermediary animal host (if there is one) is still unidentified. Previous theories about intermediary hosts, like snakes sold in these "wet markets," have already been abandoned, with more recent theories about anteater-like pangolins serving as the intermediary hosts being dubious, as most of the already-illegal pangolin trade is for their dried scales, where viruses are unlikely to persist.

Early in the outbreak, a Lancet study (1/24/20) found that roughly a third of the first hospitalized patients--13 of 41--had no connection to the Huanan Market that featured so prominently in early reports regarding the timeline of the virus (e.g., Washington Post, 1/26/20; New York Times, 2/1/20), with the first patient having no reported link to the seafood market, as well as there being "no epidemiological link" between "the first patient and later cases."

When Science magazine (1/26/20) reported on the Lancet's findings, it noted that if their findings are correct, then the first infections must have occurred in November 2019--if not earlier--because of the incubation time between infection and symptoms surfacing. Although "Patient Zero" has yet to be identified, the South China Morning Post (3/13/20) seemed to confirm this hypothesis when it found that updated Chinese government data has traced the first case of someone in China suffering from Covid-19 symptoms to a 55-year-old resident of Hubei province on November 17, 2019.

All this casts doubt upon the Huanan Market being the source of the outbreak.

Yet one can find op-eds regularly echoing longstanding racist stereotypes in corporate media, seemingly without any knowledge or interest in what these "wet markets" actually are. One journalist formerly based in Shanghai claimed in USA Today (4/8/20) that the "strangest animals for human consumption" to his "Western eyes" were "turtles, snakes and frogs," before condemning Chinese "cultural traditions of medicine, animal husbandry and culinary tastes" for being a "unique incubator of terrible diseases." Georgetown professor Bradley Blakeman wrote a patronizing op-ed (The Hill, 4/1/20) arguing that "China's domestic demand and customs for exotic and live food are a direct threat to the health, safety and welfare of the world," calling on the world to focus on the "domestic food laws" of countries like China, where they aren't meeting "standards of health, safety and welfare."

One can also find articles pointing out the recognizable unsanitary eating habits of Americans (CNN, 8/10/17). Exotic meat like turtles, snakes, frogs, squirrels, camels and alligators can be eaten in the US as well, yet no one is singling the US out for the peculiar eating habits of some Americans. Neither are wildlife markets unique to Asia, as there are 80 slaughterhouses and live animal markets in New York City alone, the current global epicenter of the pandemic.

Corporate media also undermined the epidemiological need to be specific about what species the Huanan Market actually contained, and in what frequency, by relying on montages from different markets across China--with little acknowledgment of when and where these pictures were taken--while omitting the significant variations in cuisine among different regions of a country populated by over 1.3 billion people. A more contextual approach would have informed audiences that wildlife actually isn't commonly eaten in China--the practice being largely restricted to the southeast region and some towns--with many Chinese people disapproving of the practice as well (one recent poll showing near 97% strong disapproval).

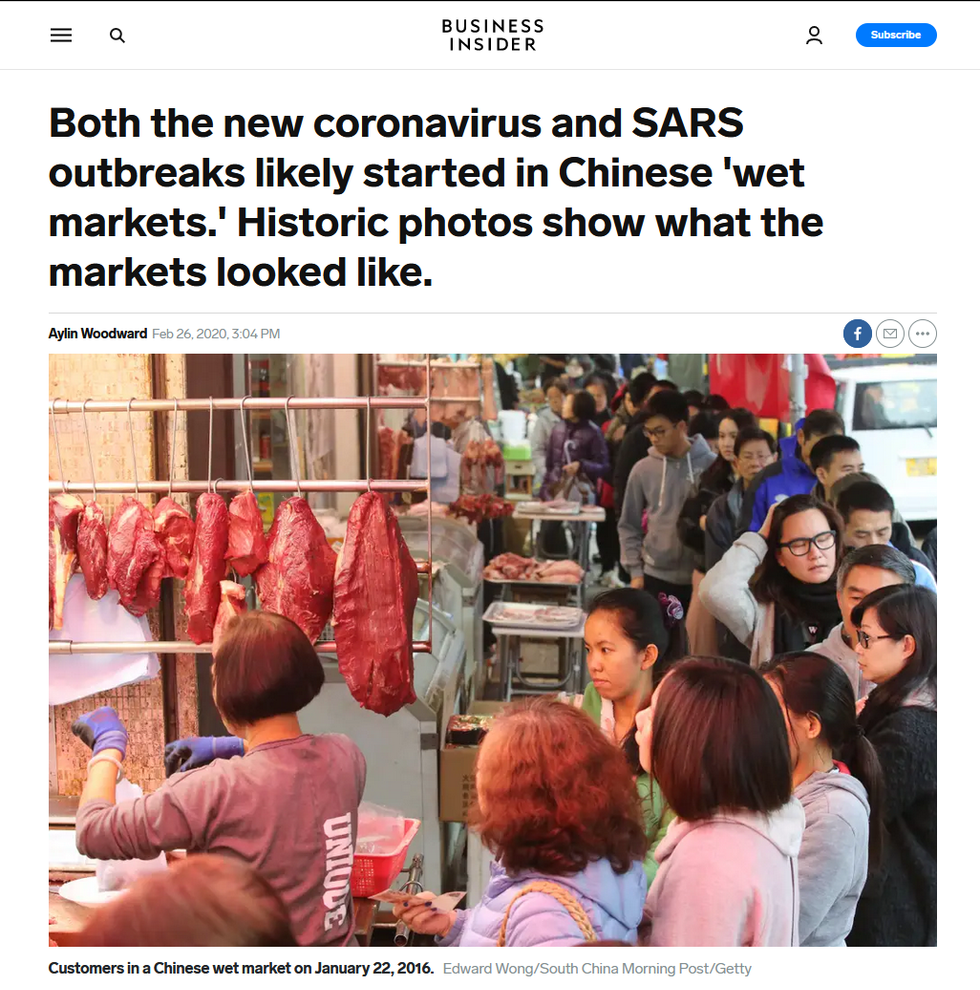

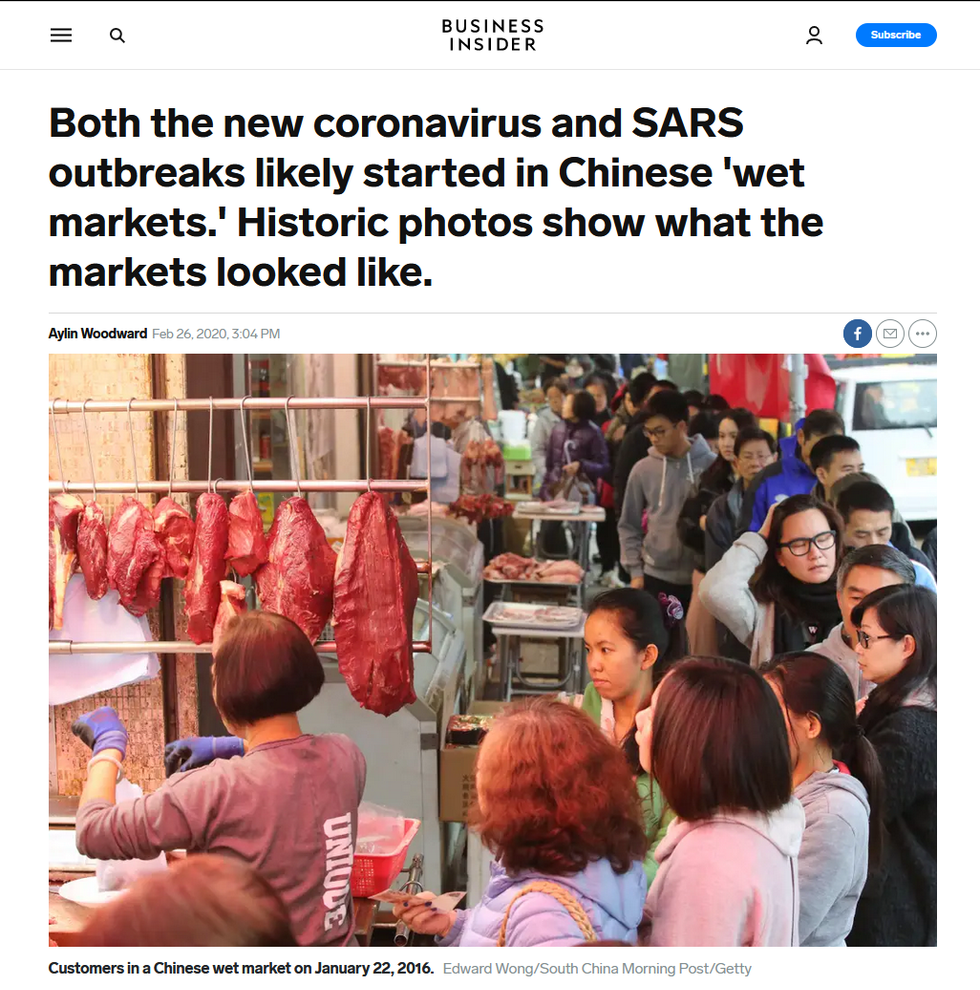

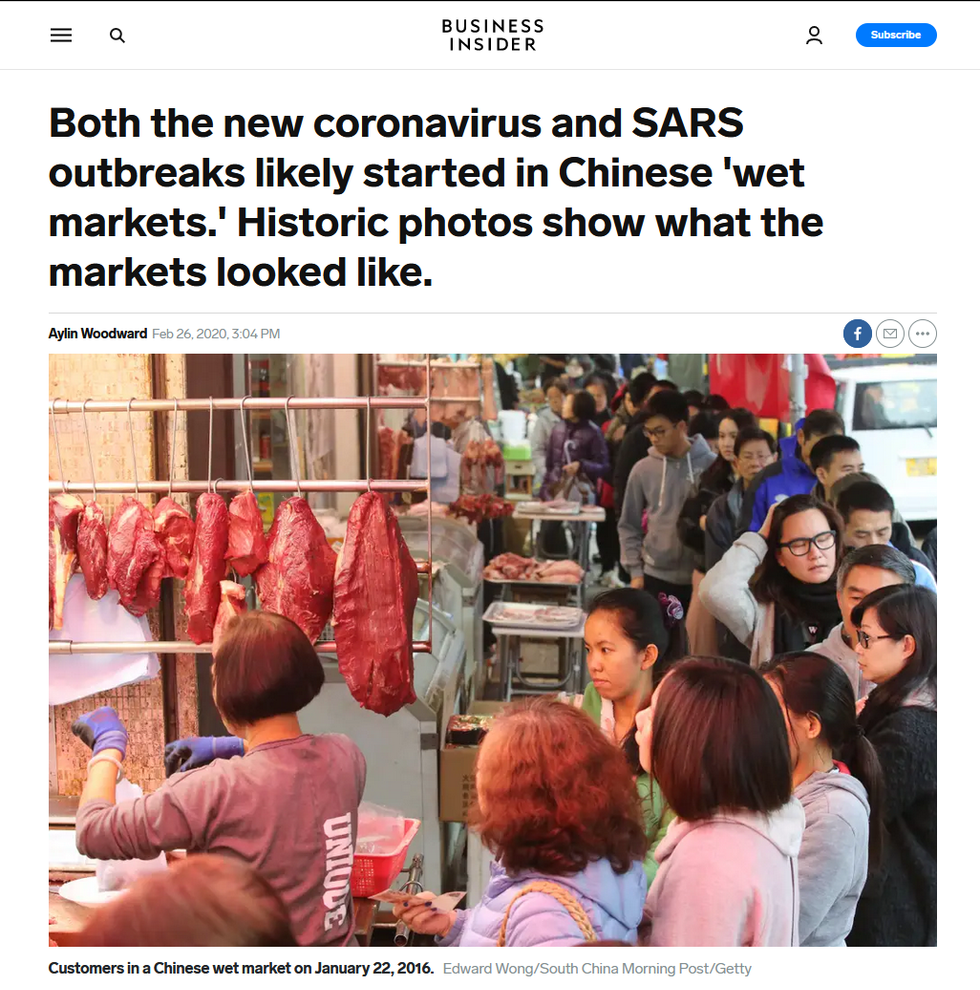

To maximize shock value, Business Insider's "Both the New Coronavirus and SARS Outbreaks Likely Started in Chinese 'Wet Markets.' Historic Photos Show What the Markets Looked Like" (2/26/20) featured numerous explicit images of wildlife being held in captivity, butchered and sold. Although Business Insider acknowledged that research since the shutdown of the infamous Huanan Market on January 1 has "indicated the market may not have been the origin of the outbreak," it nevertheless cited sources claiming that these "pandemics" are "more likely to originate in the Far East because of the close contact with live animals [and] the density of the population." It also needlessly invoked the stereotype of Asians eating dogs, despite its history of being used to justify American colonization, and having no connection to the virus:

Wet markets put people and live and dead animals--dogs, chickens, pigs, snakes, civets and more--in constant close contact. That makes it easy for zoonotic diseases to jump from animals to humans....

Wet markets like Huanan are common in China. They're called wet markets because vendors often slaughter animals in front of customers.

NPR's "Why They're Called 'Wet Markets'--and What Health Risks They Might Pose" (1/31/20) also featured images designed to stoke horror and distrust of Chinese food and hygiene, when it claimed to explain why "wet markets in mainland China" are "particularly problematic," and why they're called that. NPR falsely asserted:

Patients who came down with disease at the end of December all had connections to the Huanan Seafood Market in Wuhan China. The complex of stalls selling live fish, meat and wild animals is known in the region as a "wet market."

Researchers believe the new virus probably mutated from a coronavirus common in animals and jumped over to humans in the Wuhan bazaar.

I visited the Tai Po wet market in Hong Kong, and it's quite obvious why the term "wet" is used. Live fish in open tubs splash water all over the floor. The countertops of the stalls are red with blood as fish are gutted and filleted right in front of the customers' eyes. Live turtles and crustaceans climb over each other in boxes. Melting ice adds to the slush on the floor. There's lots of water, blood, fish scales and chicken guts. Things are wet.

Although Fox News's "China's Wet Markets Can Include these Bizarre, Unusual Items" (4/9/20) also acknowledged that "scientists have not yet determined exactly how the new coronavirus infected people," it still offered more sensationalist coverage by featuring graphic images of the scandalous items featured for sale in these markets (also featuring dogs):

But these kinds of wet markets, which have long included bizarre and unusual items, are known to operate in not the most sanitary conditions....

"Wet markets," as defined by the Oxford English Dictionary, are places "for the sale of fresh meat, fish and produce." They also sell an array of exotic animals.

And like many other "wet markets" in Asia and elsewhere, the animals at the Wuhan market lived in close proximity as they were tied up or stacked in cages.

Despite what these reports claim, "wet markets" are not called that because there's a lot of blood and water all over the place, where vendors often slaughter animals in front of customers. And neither should "wet markets" be confused with wildlife markets--as many journalists frequently do--since the vast majority of wet markets don't keep or sell wildlife.

While it's true that China's wildlife regulations could be improved, "wet market" is a blanket term used to describe any market that sells fresh produce and other perishable goods in an open air setting. They are called "wet markets" because they don't primarily sell "dry" nonperishable goods, like packaged noodles found in supermarkets; the "wet" comes from melting ice used to keep seafood fresh, as well as shop owners hosing down their stalls to keep their fresh produce clean (Quartz, 4/16/20).

Media coverage like the above also regularly omits the cultural, nutritional and economic importance of these wet markets for millions of Chinese people (Earth Island Journal, 4/13/20). Wet markets serve an important function by fostering interpersonal relationships, passing down cultural food knowledge, in addition to offering more nutritious food at lower prices for low-income families, compared to the processed food containing higher amounts of salt and sugar found in supermarkets (LA Times, 3/11/20). Although supermarkets now account for about half of all grocery spending in China, the attraction of wet markets is similar to the appeal of Western farmers markets, and the low prevalence of food-borne microbial illnesses in East Asia suggests they aren't cesspools of disease, but generally do a good job of providing households with affordable and fresh produce (Washington Post, 4/5/20).

More importantly, as anthropologists Christos Lynteris and Lyle Fearnley pointed out (The Conversation, 1/31/20):

Where [wet] markets do contain what many Western media portray as "wild animals," the majority of these are actually bred and farmed in captivity, such as mallard ducks, frogs or snakes. Only a smaller proportion of animals are actually poached from the wild for sale.

For the sake of argument, even if we were to assume that Covid-19 emerged from the Huanan Market, it still isn't obvious why China should be blamed for the pandemic. What is perhaps most omitted in the discussion of Chinese wet markets is the perspective of farmers, producers and vendors. Although media reports often marvel at the consumption of wild animals, little is said about why farmers produce them.

When one investigates why some Chinese farmers engage in the wildlife trade, it's because the Chinese Communist Party once encouraged the wildlife trade as part of their strategy of state-directed rapid industrialization financed by foreign investment. The Chinese government pursued this path in order to overcome the economic devastation inherited in the aftermath of the Century of Humiliation by Western and Japanese colonialism, as well as to avoid the counterrevolutionary hostility from the US that led to the USSR's collapse (Monthly Review, 3/31/08). When China industrialized its food production system as part of this strategy--and pushed out smallholding farmers from the livestock industry in the process--some of them turned to the increasingly lucrative wildlife trade encouraged by globalization (and corporate media) to survive.

More astute journalists have already connected the increasing frequency of zoonotic pandemics like Covid-19 to larger systemic causes, rather than offering simplistic and culturally biased condemnations of Chinese hygiene and eating habits. Several have pointed out that Covid-19's emergence is inseparable from globalization and the ongoing climate crisis, as humans are devastating the natural habitats of many species by altering terrestrial and marine environments, which then increases the nature and frequency of human contact with wildlife harboring diseases. This health and climate crisis is also inseparable from industrial food production and meat-eating habits around the world coming from the cesspools of filth and disease we call factory farms (Al-Jazeera, 3/30/20; Vox, 4/22/20).

So when we read reports condemning China's pollution and previous encouragement of the wildlife trade (omitting the US's role and China's impressive environmental progress), it's important to keep the complex legacy of colonialism in mind before issuing hasty and hypocritical condemnations. It's easy to point fingers at Chinese "wet markets" to distract from the US's failures, but US journalists should prioritize holding their own government accountable, and connecting seemingly isolated issues to larger causes.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

The stigmatization of Asian people and their culture as "inferior" or "exotic" isn't a new phenomenon. What is considered acceptable or "strange" meat is often the result of arbitrary cultural norms, and Chinese food has often suffered from hypocritical cultural appropriation once it became popular, before being stigmatized again by racist and propagandistic news coverage following the Covid-19 outbreak (FAIR.org, 3/6/20, 3/24/20). Alongside a spike in hate crimes against Asian people are reports of Asian restaurants and other businesses--especially those owned and run by Chinese people--struggling to survive because of resurging racist stereotypes about "dirty" Chinese eating habits.

As James Palmer noted in Foreign Policy (1/27/20), debunking a widely circulated video of a supposed ordinary Chinese woman in Wuhan biting into a whole bat (the featured woman was the host of an online travel show, eating in the Micronesian nation of Palau), Americans have long branded Chinese people as carriers of disease. For example, in 1854, the New York Tribune wrote that Chinese people were "uncivilized, unclean, filthy beyond all conception."

And if there's a reason why it's widely believed that the novel coronavirus emerged in a Chinese "wet market" in Wuhan, it's because many of the earliest reports treated this origin theory as fact.

The South China Morning Post (1/22/20) reported that "exotic animals" were "available at a wet market in the central Chinese city of Wuhan that is ground zero of a new virus," with many of those infected having lived or worked near the Huanan Wholesale Seafood Market, which experts "believe is the source of the virus." The New York Times' "China's Omnivorous Markets Are in the Eye of a Lethal Outbreak Once Again" (1/25/20) reported that "the markets are fixtures in scores of Chinese cities," and "they are the source of an epidemic." The Wall Street Journal (1/26/20) reported that the "carcasses and live specimens" found in the Huanan Market are "typical of the wet markets where most people in this country buy their food," making China a "hot spot for such outbreaks," with its "long tradition of eating wildlife."

While the possibility of Covid-19 emerging from these so-called "wet markets" hasn't been eliminated, it is not at all certain that the virus emerged from these markets. When CNN (4/6/20) interviewed several virus experts for a report on the various origin theories of Covid-19, all of them acknowledged that anyone who claims to know the origins of the outbreak with certainty is "guessing," with the experts reportedly "at odds" over the "once widely accepted theory that the virus originated at a wet market."

New information is constantly being updated, and while scientists currently seem confident that the virus initially spilled over from bats, because they're considered to be natural hosts of coronaviruses, the intermediary animal host (if there is one) is still unidentified. Previous theories about intermediary hosts, like snakes sold in these "wet markets," have already been abandoned, with more recent theories about anteater-like pangolins serving as the intermediary hosts being dubious, as most of the already-illegal pangolin trade is for their dried scales, where viruses are unlikely to persist.

Early in the outbreak, a Lancet study (1/24/20) found that roughly a third of the first hospitalized patients--13 of 41--had no connection to the Huanan Market that featured so prominently in early reports regarding the timeline of the virus (e.g., Washington Post, 1/26/20; New York Times, 2/1/20), with the first patient having no reported link to the seafood market, as well as there being "no epidemiological link" between "the first patient and later cases."

When Science magazine (1/26/20) reported on the Lancet's findings, it noted that if their findings are correct, then the first infections must have occurred in November 2019--if not earlier--because of the incubation time between infection and symptoms surfacing. Although "Patient Zero" has yet to be identified, the South China Morning Post (3/13/20) seemed to confirm this hypothesis when it found that updated Chinese government data has traced the first case of someone in China suffering from Covid-19 symptoms to a 55-year-old resident of Hubei province on November 17, 2019.

All this casts doubt upon the Huanan Market being the source of the outbreak.

Yet one can find op-eds regularly echoing longstanding racist stereotypes in corporate media, seemingly without any knowledge or interest in what these "wet markets" actually are. One journalist formerly based in Shanghai claimed in USA Today (4/8/20) that the "strangest animals for human consumption" to his "Western eyes" were "turtles, snakes and frogs," before condemning Chinese "cultural traditions of medicine, animal husbandry and culinary tastes" for being a "unique incubator of terrible diseases." Georgetown professor Bradley Blakeman wrote a patronizing op-ed (The Hill, 4/1/20) arguing that "China's domestic demand and customs for exotic and live food are a direct threat to the health, safety and welfare of the world," calling on the world to focus on the "domestic food laws" of countries like China, where they aren't meeting "standards of health, safety and welfare."

One can also find articles pointing out the recognizable unsanitary eating habits of Americans (CNN, 8/10/17). Exotic meat like turtles, snakes, frogs, squirrels, camels and alligators can be eaten in the US as well, yet no one is singling the US out for the peculiar eating habits of some Americans. Neither are wildlife markets unique to Asia, as there are 80 slaughterhouses and live animal markets in New York City alone, the current global epicenter of the pandemic.

Corporate media also undermined the epidemiological need to be specific about what species the Huanan Market actually contained, and in what frequency, by relying on montages from different markets across China--with little acknowledgment of when and where these pictures were taken--while omitting the significant variations in cuisine among different regions of a country populated by over 1.3 billion people. A more contextual approach would have informed audiences that wildlife actually isn't commonly eaten in China--the practice being largely restricted to the southeast region and some towns--with many Chinese people disapproving of the practice as well (one recent poll showing near 97% strong disapproval).

To maximize shock value, Business Insider's "Both the New Coronavirus and SARS Outbreaks Likely Started in Chinese 'Wet Markets.' Historic Photos Show What the Markets Looked Like" (2/26/20) featured numerous explicit images of wildlife being held in captivity, butchered and sold. Although Business Insider acknowledged that research since the shutdown of the infamous Huanan Market on January 1 has "indicated the market may not have been the origin of the outbreak," it nevertheless cited sources claiming that these "pandemics" are "more likely to originate in the Far East because of the close contact with live animals [and] the density of the population." It also needlessly invoked the stereotype of Asians eating dogs, despite its history of being used to justify American colonization, and having no connection to the virus:

Wet markets put people and live and dead animals--dogs, chickens, pigs, snakes, civets and more--in constant close contact. That makes it easy for zoonotic diseases to jump from animals to humans....

Wet markets like Huanan are common in China. They're called wet markets because vendors often slaughter animals in front of customers.

NPR's "Why They're Called 'Wet Markets'--and What Health Risks They Might Pose" (1/31/20) also featured images designed to stoke horror and distrust of Chinese food and hygiene, when it claimed to explain why "wet markets in mainland China" are "particularly problematic," and why they're called that. NPR falsely asserted:

Patients who came down with disease at the end of December all had connections to the Huanan Seafood Market in Wuhan China. The complex of stalls selling live fish, meat and wild animals is known in the region as a "wet market."

Researchers believe the new virus probably mutated from a coronavirus common in animals and jumped over to humans in the Wuhan bazaar.

I visited the Tai Po wet market in Hong Kong, and it's quite obvious why the term "wet" is used. Live fish in open tubs splash water all over the floor. The countertops of the stalls are red with blood as fish are gutted and filleted right in front of the customers' eyes. Live turtles and crustaceans climb over each other in boxes. Melting ice adds to the slush on the floor. There's lots of water, blood, fish scales and chicken guts. Things are wet.

Although Fox News's "China's Wet Markets Can Include these Bizarre, Unusual Items" (4/9/20) also acknowledged that "scientists have not yet determined exactly how the new coronavirus infected people," it still offered more sensationalist coverage by featuring graphic images of the scandalous items featured for sale in these markets (also featuring dogs):

But these kinds of wet markets, which have long included bizarre and unusual items, are known to operate in not the most sanitary conditions....

"Wet markets," as defined by the Oxford English Dictionary, are places "for the sale of fresh meat, fish and produce." They also sell an array of exotic animals.

And like many other "wet markets" in Asia and elsewhere, the animals at the Wuhan market lived in close proximity as they were tied up or stacked in cages.

Despite what these reports claim, "wet markets" are not called that because there's a lot of blood and water all over the place, where vendors often slaughter animals in front of customers. And neither should "wet markets" be confused with wildlife markets--as many journalists frequently do--since the vast majority of wet markets don't keep or sell wildlife.

While it's true that China's wildlife regulations could be improved, "wet market" is a blanket term used to describe any market that sells fresh produce and other perishable goods in an open air setting. They are called "wet markets" because they don't primarily sell "dry" nonperishable goods, like packaged noodles found in supermarkets; the "wet" comes from melting ice used to keep seafood fresh, as well as shop owners hosing down their stalls to keep their fresh produce clean (Quartz, 4/16/20).

Media coverage like the above also regularly omits the cultural, nutritional and economic importance of these wet markets for millions of Chinese people (Earth Island Journal, 4/13/20). Wet markets serve an important function by fostering interpersonal relationships, passing down cultural food knowledge, in addition to offering more nutritious food at lower prices for low-income families, compared to the processed food containing higher amounts of salt and sugar found in supermarkets (LA Times, 3/11/20). Although supermarkets now account for about half of all grocery spending in China, the attraction of wet markets is similar to the appeal of Western farmers markets, and the low prevalence of food-borne microbial illnesses in East Asia suggests they aren't cesspools of disease, but generally do a good job of providing households with affordable and fresh produce (Washington Post, 4/5/20).

More importantly, as anthropologists Christos Lynteris and Lyle Fearnley pointed out (The Conversation, 1/31/20):

Where [wet] markets do contain what many Western media portray as "wild animals," the majority of these are actually bred and farmed in captivity, such as mallard ducks, frogs or snakes. Only a smaller proportion of animals are actually poached from the wild for sale.

For the sake of argument, even if we were to assume that Covid-19 emerged from the Huanan Market, it still isn't obvious why China should be blamed for the pandemic. What is perhaps most omitted in the discussion of Chinese wet markets is the perspective of farmers, producers and vendors. Although media reports often marvel at the consumption of wild animals, little is said about why farmers produce them.

When one investigates why some Chinese farmers engage in the wildlife trade, it's because the Chinese Communist Party once encouraged the wildlife trade as part of their strategy of state-directed rapid industrialization financed by foreign investment. The Chinese government pursued this path in order to overcome the economic devastation inherited in the aftermath of the Century of Humiliation by Western and Japanese colonialism, as well as to avoid the counterrevolutionary hostility from the US that led to the USSR's collapse (Monthly Review, 3/31/08). When China industrialized its food production system as part of this strategy--and pushed out smallholding farmers from the livestock industry in the process--some of them turned to the increasingly lucrative wildlife trade encouraged by globalization (and corporate media) to survive.

More astute journalists have already connected the increasing frequency of zoonotic pandemics like Covid-19 to larger systemic causes, rather than offering simplistic and culturally biased condemnations of Chinese hygiene and eating habits. Several have pointed out that Covid-19's emergence is inseparable from globalization and the ongoing climate crisis, as humans are devastating the natural habitats of many species by altering terrestrial and marine environments, which then increases the nature and frequency of human contact with wildlife harboring diseases. This health and climate crisis is also inseparable from industrial food production and meat-eating habits around the world coming from the cesspools of filth and disease we call factory farms (Al-Jazeera, 3/30/20; Vox, 4/22/20).

So when we read reports condemning China's pollution and previous encouragement of the wildlife trade (omitting the US's role and China's impressive environmental progress), it's important to keep the complex legacy of colonialism in mind before issuing hasty and hypocritical condemnations. It's easy to point fingers at Chinese "wet markets" to distract from the US's failures, but US journalists should prioritize holding their own government accountable, and connecting seemingly isolated issues to larger causes.

The stigmatization of Asian people and their culture as "inferior" or "exotic" isn't a new phenomenon. What is considered acceptable or "strange" meat is often the result of arbitrary cultural norms, and Chinese food has often suffered from hypocritical cultural appropriation once it became popular, before being stigmatized again by racist and propagandistic news coverage following the Covid-19 outbreak (FAIR.org, 3/6/20, 3/24/20). Alongside a spike in hate crimes against Asian people are reports of Asian restaurants and other businesses--especially those owned and run by Chinese people--struggling to survive because of resurging racist stereotypes about "dirty" Chinese eating habits.

As James Palmer noted in Foreign Policy (1/27/20), debunking a widely circulated video of a supposed ordinary Chinese woman in Wuhan biting into a whole bat (the featured woman was the host of an online travel show, eating in the Micronesian nation of Palau), Americans have long branded Chinese people as carriers of disease. For example, in 1854, the New York Tribune wrote that Chinese people were "uncivilized, unclean, filthy beyond all conception."

And if there's a reason why it's widely believed that the novel coronavirus emerged in a Chinese "wet market" in Wuhan, it's because many of the earliest reports treated this origin theory as fact.

The South China Morning Post (1/22/20) reported that "exotic animals" were "available at a wet market in the central Chinese city of Wuhan that is ground zero of a new virus," with many of those infected having lived or worked near the Huanan Wholesale Seafood Market, which experts "believe is the source of the virus." The New York Times' "China's Omnivorous Markets Are in the Eye of a Lethal Outbreak Once Again" (1/25/20) reported that "the markets are fixtures in scores of Chinese cities," and "they are the source of an epidemic." The Wall Street Journal (1/26/20) reported that the "carcasses and live specimens" found in the Huanan Market are "typical of the wet markets where most people in this country buy their food," making China a "hot spot for such outbreaks," with its "long tradition of eating wildlife."

While the possibility of Covid-19 emerging from these so-called "wet markets" hasn't been eliminated, it is not at all certain that the virus emerged from these markets. When CNN (4/6/20) interviewed several virus experts for a report on the various origin theories of Covid-19, all of them acknowledged that anyone who claims to know the origins of the outbreak with certainty is "guessing," with the experts reportedly "at odds" over the "once widely accepted theory that the virus originated at a wet market."

New information is constantly being updated, and while scientists currently seem confident that the virus initially spilled over from bats, because they're considered to be natural hosts of coronaviruses, the intermediary animal host (if there is one) is still unidentified. Previous theories about intermediary hosts, like snakes sold in these "wet markets," have already been abandoned, with more recent theories about anteater-like pangolins serving as the intermediary hosts being dubious, as most of the already-illegal pangolin trade is for their dried scales, where viruses are unlikely to persist.

Early in the outbreak, a Lancet study (1/24/20) found that roughly a third of the first hospitalized patients--13 of 41--had no connection to the Huanan Market that featured so prominently in early reports regarding the timeline of the virus (e.g., Washington Post, 1/26/20; New York Times, 2/1/20), with the first patient having no reported link to the seafood market, as well as there being "no epidemiological link" between "the first patient and later cases."

When Science magazine (1/26/20) reported on the Lancet's findings, it noted that if their findings are correct, then the first infections must have occurred in November 2019--if not earlier--because of the incubation time between infection and symptoms surfacing. Although "Patient Zero" has yet to be identified, the South China Morning Post (3/13/20) seemed to confirm this hypothesis when it found that updated Chinese government data has traced the first case of someone in China suffering from Covid-19 symptoms to a 55-year-old resident of Hubei province on November 17, 2019.

All this casts doubt upon the Huanan Market being the source of the outbreak.

Yet one can find op-eds regularly echoing longstanding racist stereotypes in corporate media, seemingly without any knowledge or interest in what these "wet markets" actually are. One journalist formerly based in Shanghai claimed in USA Today (4/8/20) that the "strangest animals for human consumption" to his "Western eyes" were "turtles, snakes and frogs," before condemning Chinese "cultural traditions of medicine, animal husbandry and culinary tastes" for being a "unique incubator of terrible diseases." Georgetown professor Bradley Blakeman wrote a patronizing op-ed (The Hill, 4/1/20) arguing that "China's domestic demand and customs for exotic and live food are a direct threat to the health, safety and welfare of the world," calling on the world to focus on the "domestic food laws" of countries like China, where they aren't meeting "standards of health, safety and welfare."

One can also find articles pointing out the recognizable unsanitary eating habits of Americans (CNN, 8/10/17). Exotic meat like turtles, snakes, frogs, squirrels, camels and alligators can be eaten in the US as well, yet no one is singling the US out for the peculiar eating habits of some Americans. Neither are wildlife markets unique to Asia, as there are 80 slaughterhouses and live animal markets in New York City alone, the current global epicenter of the pandemic.

Corporate media also undermined the epidemiological need to be specific about what species the Huanan Market actually contained, and in what frequency, by relying on montages from different markets across China--with little acknowledgment of when and where these pictures were taken--while omitting the significant variations in cuisine among different regions of a country populated by over 1.3 billion people. A more contextual approach would have informed audiences that wildlife actually isn't commonly eaten in China--the practice being largely restricted to the southeast region and some towns--with many Chinese people disapproving of the practice as well (one recent poll showing near 97% strong disapproval).

To maximize shock value, Business Insider's "Both the New Coronavirus and SARS Outbreaks Likely Started in Chinese 'Wet Markets.' Historic Photos Show What the Markets Looked Like" (2/26/20) featured numerous explicit images of wildlife being held in captivity, butchered and sold. Although Business Insider acknowledged that research since the shutdown of the infamous Huanan Market on January 1 has "indicated the market may not have been the origin of the outbreak," it nevertheless cited sources claiming that these "pandemics" are "more likely to originate in the Far East because of the close contact with live animals [and] the density of the population." It also needlessly invoked the stereotype of Asians eating dogs, despite its history of being used to justify American colonization, and having no connection to the virus:

Wet markets put people and live and dead animals--dogs, chickens, pigs, snakes, civets and more--in constant close contact. That makes it easy for zoonotic diseases to jump from animals to humans....

Wet markets like Huanan are common in China. They're called wet markets because vendors often slaughter animals in front of customers.

NPR's "Why They're Called 'Wet Markets'--and What Health Risks They Might Pose" (1/31/20) also featured images designed to stoke horror and distrust of Chinese food and hygiene, when it claimed to explain why "wet markets in mainland China" are "particularly problematic," and why they're called that. NPR falsely asserted:

Patients who came down with disease at the end of December all had connections to the Huanan Seafood Market in Wuhan China. The complex of stalls selling live fish, meat and wild animals is known in the region as a "wet market."

Researchers believe the new virus probably mutated from a coronavirus common in animals and jumped over to humans in the Wuhan bazaar.

I visited the Tai Po wet market in Hong Kong, and it's quite obvious why the term "wet" is used. Live fish in open tubs splash water all over the floor. The countertops of the stalls are red with blood as fish are gutted and filleted right in front of the customers' eyes. Live turtles and crustaceans climb over each other in boxes. Melting ice adds to the slush on the floor. There's lots of water, blood, fish scales and chicken guts. Things are wet.

Although Fox News's "China's Wet Markets Can Include these Bizarre, Unusual Items" (4/9/20) also acknowledged that "scientists have not yet determined exactly how the new coronavirus infected people," it still offered more sensationalist coverage by featuring graphic images of the scandalous items featured for sale in these markets (also featuring dogs):

But these kinds of wet markets, which have long included bizarre and unusual items, are known to operate in not the most sanitary conditions....

"Wet markets," as defined by the Oxford English Dictionary, are places "for the sale of fresh meat, fish and produce." They also sell an array of exotic animals.

And like many other "wet markets" in Asia and elsewhere, the animals at the Wuhan market lived in close proximity as they were tied up or stacked in cages.

Despite what these reports claim, "wet markets" are not called that because there's a lot of blood and water all over the place, where vendors often slaughter animals in front of customers. And neither should "wet markets" be confused with wildlife markets--as many journalists frequently do--since the vast majority of wet markets don't keep or sell wildlife.

While it's true that China's wildlife regulations could be improved, "wet market" is a blanket term used to describe any market that sells fresh produce and other perishable goods in an open air setting. They are called "wet markets" because they don't primarily sell "dry" nonperishable goods, like packaged noodles found in supermarkets; the "wet" comes from melting ice used to keep seafood fresh, as well as shop owners hosing down their stalls to keep their fresh produce clean (Quartz, 4/16/20).

Media coverage like the above also regularly omits the cultural, nutritional and economic importance of these wet markets for millions of Chinese people (Earth Island Journal, 4/13/20). Wet markets serve an important function by fostering interpersonal relationships, passing down cultural food knowledge, in addition to offering more nutritious food at lower prices for low-income families, compared to the processed food containing higher amounts of salt and sugar found in supermarkets (LA Times, 3/11/20). Although supermarkets now account for about half of all grocery spending in China, the attraction of wet markets is similar to the appeal of Western farmers markets, and the low prevalence of food-borne microbial illnesses in East Asia suggests they aren't cesspools of disease, but generally do a good job of providing households with affordable and fresh produce (Washington Post, 4/5/20).

More importantly, as anthropologists Christos Lynteris and Lyle Fearnley pointed out (The Conversation, 1/31/20):

Where [wet] markets do contain what many Western media portray as "wild animals," the majority of these are actually bred and farmed in captivity, such as mallard ducks, frogs or snakes. Only a smaller proportion of animals are actually poached from the wild for sale.

For the sake of argument, even if we were to assume that Covid-19 emerged from the Huanan Market, it still isn't obvious why China should be blamed for the pandemic. What is perhaps most omitted in the discussion of Chinese wet markets is the perspective of farmers, producers and vendors. Although media reports often marvel at the consumption of wild animals, little is said about why farmers produce them.

When one investigates why some Chinese farmers engage in the wildlife trade, it's because the Chinese Communist Party once encouraged the wildlife trade as part of their strategy of state-directed rapid industrialization financed by foreign investment. The Chinese government pursued this path in order to overcome the economic devastation inherited in the aftermath of the Century of Humiliation by Western and Japanese colonialism, as well as to avoid the counterrevolutionary hostility from the US that led to the USSR's collapse (Monthly Review, 3/31/08). When China industrialized its food production system as part of this strategy--and pushed out smallholding farmers from the livestock industry in the process--some of them turned to the increasingly lucrative wildlife trade encouraged by globalization (and corporate media) to survive.

More astute journalists have already connected the increasing frequency of zoonotic pandemics like Covid-19 to larger systemic causes, rather than offering simplistic and culturally biased condemnations of Chinese hygiene and eating habits. Several have pointed out that Covid-19's emergence is inseparable from globalization and the ongoing climate crisis, as humans are devastating the natural habitats of many species by altering terrestrial and marine environments, which then increases the nature and frequency of human contact with wildlife harboring diseases. This health and climate crisis is also inseparable from industrial food production and meat-eating habits around the world coming from the cesspools of filth and disease we call factory farms (Al-Jazeera, 3/30/20; Vox, 4/22/20).

So when we read reports condemning China's pollution and previous encouragement of the wildlife trade (omitting the US's role and China's impressive environmental progress), it's important to keep the complex legacy of colonialism in mind before issuing hasty and hypocritical condemnations. It's easy to point fingers at Chinese "wet markets" to distract from the US's failures, but US journalists should prioritize holding their own government accountable, and connecting seemingly isolated issues to larger causes.