SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

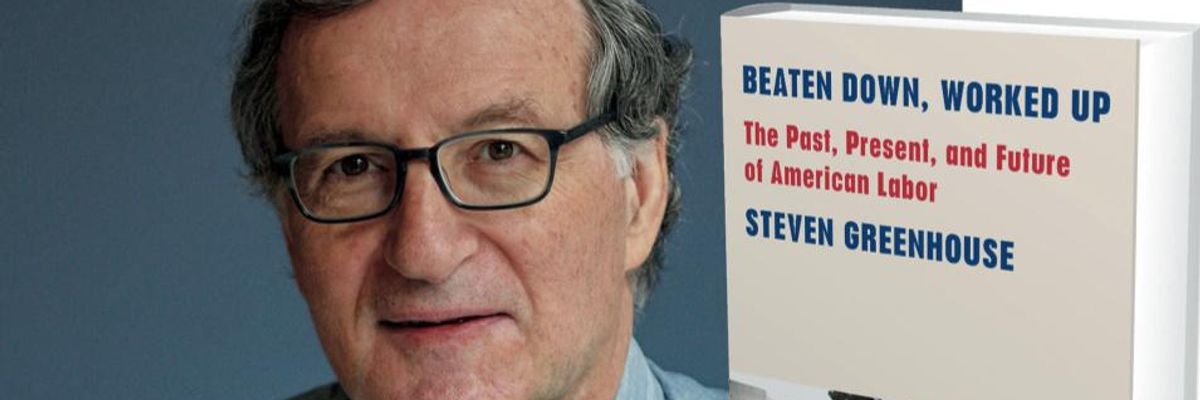

Veteran journalist Steven Greenhouse is the author of the new book Beaten Down, Worked Up: The Past, Present and Future of American Labor. (Photo: Michael Lionstar / Penguin Random House)

This past Saturday was the annual Labor Day Parade in New York City. They don't have it on the actual holiday anymore - too many people are more interested in a long, late summer weekend in the mountains or at the beach.

And yet the parade itself is a grand celebration of unions, even if in recent experience, there are more people marching up Fifth Avenue than on the sidewalk watching.

In a nutshell, that's kind of the state of organized labor in America these days; enthusiasm among those of us who are members of unions, who enjoy the power of solidarity at the bargaining table and fiercely believe in the importance of labor when it comes to fighting economic inequity, versus a public that too often reacts with indifference or even outright hostility.

But that's changing. There are signs of encouragement that come from both a vivid history, despite calamities along the way, and the growing realization among people that especially in these days of Trump and a corporate America running roughshod over working men and women there's a vital need to come together in the name of self-preservation and resistance.

In the interest of full disclosure, I was president of an AFL-CIO union, the Writers Guild of America East, for ten years and currently serve on its council. I've seen firsthand the strength that organized people in a union can bring to bear against organized money and influence.

That's one reason it was a pleasure to sit down last week with Steven Greenhouse, author of the new book Beaten Down, Worked Up: The Past, Present and Future of American Labor. Washington Post columnist E.J. Dionne described it as "an excellent account of how important strong unions were in moving our nation toward greater economic and social justice, and how the decline has increased inequality, and unfairness." But there is hope in this book as well, evidence of renewed recognition of the nation's workers as a growing force to be reckoned with once again.

Greenhouse spent three decades at The New York Times, 19 of them as its labor and workplace correspondent. He published his first book, The Big Squeeze: Tough Times for the American Worker, in 2009 and now brings his expertise in workplace issues to a number of publications including The Times, and The Guardian, The American Prospect, Time magazine, and the Columbia Journalism Review.

Our conversation is below, edited in some places for clarity, and also can be heard via SoundCloud:

We're recording this just a couple of days after the Labor Day weekend and it strikes me that increasingly we have lost sight of the significance of that holiday. What has happened to American labor, and why are our citizens so ignorant of its history?

It is upsetting that so many Americans are ignorant about Labor Day and labor unions. One of the reasons my editor asked me to write the book was that there was a great concern that tens of millions of Americans know far too little about unions, far too little about labor, far too little about what unions have accomplished over the decades for American workers. They've really played a pivotal role in creating the middle class. I love the bumper sticker and it's really true, "Unions: The Folks who Brought You the Weekend."

I think in school nowadays, a lot of students don't learn anything about, or learn very little about unions. And I can only begin to imagine what anti-union states like Mississippi and Alabama teach about unions. There isn't enough coverage of average workers and what they face in the news media. There are some labor reporters on some of the vigorous new websites, like Huffington Post, and Vox. But the TV networks don't do enough, the radio networks don't do enough. There's lots of coverage about tariffs, and Wall Street, but very little about how tough it is for many millions of workers to make ends meet.

We keep hearing Donald Trump say, "I've made American great again. It's the best thing ever." Well, 40% of the American people can't afford to pay a $400 bill. So we have problems. And I wrote this book to really shine a light on the problems American workers face, and that's caused in part by the decline in unions. [But] I also write about what can be done to rebuild worker power to help create a fairer, more democratic America.

You've structured [the book] in a very interesting and I think highly readable way, by telling us stories of individuals from around the country and their struggles to make a living. Terrence Wise and his family are a good example. Can you tell me about them?

I was doing a radio interview and there's a fast food worker on from Kansas City, Terrence Wise. He says he works full-time at Burger King, and full-time at Pizza Hut. He and his family were homeless at the time because one of the fast food chains had cut his hours back, and his fiancee, a home care worker, had hurt her back badly. So, even though he was basically working two full-time jobs, he, his fiancee and their three daughters were homeless.

I interviewed him later in the day, and he told me he was once studying for the clergy, but he had to drop out of school because he couldn't make ends meet. So I went to Kansas City, I wrote a profile of him for The New York Times.

He said, "I'm a fast food worker, I push for a $15 wage. All these people come in and say, 'You should go to college. That's how you should raise your income. Don't protest for higher wages.'" And he said, "I'd love to go to college. I have three daughters. I just can't drop my job and go to college."

[Even] if all the fast food workers, and all the home care aides, and all the cleaners and janitors went to college to improve their education, to get higher wages, we're still going to need millions and millions of fast food workers and home care workers, cleaners, and janitors. And they should not be consigned to poverty wages of $7.25 an hour. Terrence Wise has a very eloquent story of working two full-time jobs; he would leave his home at 6:00 AM to head to the first job before his three daughters got up. He'd finish one job around 3:00, then he'd go to the other job, and often get home after midnight, after his daughters had gone to sleep. And his daughters were complaining, "Hey, dad, we never see you anymore."

How would a union change his life?

It would win him higher wages, it would perhaps mean improved staff -- he said that on a weekday normally, 12, 14 people work prime shifts at the restaurant. On Sundays, there are only four people who work. But on Sundays in Kansas City there often are big football games where millions of people mob downtown to go to the stadium. But there are just four people working. He says, "We work our tails off." And if there were union, that could help improve staffing levels, he might have to worry less if he ever complained about bad conditions, or a bullying boss. He won't have to worry so much about being arbitrarily fired for speaking out. Unions would help protect him.

You begin by laying out a great many disturbing facts and figures about the state of labor in this country, noting that the United States now has the weakest labor movement of any industrial nation -- and that too often, employers fail to show workers basic respect. What happened? What changed?

I covered labor and workplace matters in The New York Times for 19 years, a pretty good stretch of time -- 200, 300 stories a year. But over 19 years, you see trends, and during the late '90s and the first decade of the 2000s, I saw that... while corporations were getting record profits -- this was years before the big recession -- things were getting worse and worse for workers. Wages were stagnant, companies, though they had record profits, were cutting back on healthcare coverage, cutting back on pensions, just trying to maximize their profits and squeeze their workers.

You ask why this is happening. Unions have grown much weaker. They've gone from representing 35% of the workforce in the 1950s, to 25% in the 1980s, now down to just over 10%; in the private sector, just over 6%.

Unions help make sure that workers are treated with dignity and respect. You have a shop steward who will talk back to a bullying boss, trying to make sure they don't treat you like dirt.

Another big change, I believe, is this focus on profit maximization. I write in the book that during World War II, unions and management really worked hand in hand, working closely together because they had a common enemy, the Nazis, the Axis. And relations were pretty good between management and labor in the 1950s and 1960s, but fast forward to the1970s. The economy faced some real crises, the oil shocks, and in the 1980s we had a horrible recession, and a huge inflow of imports. So corporate America said, "Hey, we have really got to get tougher on workers. This cooperation in the '50s and '60s, that's not the way to go. We've got to increase our profits."

So, they got much tougher on workers, much tougher on labor unions, and in 1980, Ronald Regan was elected as a conservative. Former head of the Screen Actor's Guild, former union president, but there was an illegal strike in his first few months in office by the air traffic controllers, and he really cracked down very, very hard to show who's boss.

He fired 11,700 air traffic controllers, and that sent a strong message both to corporate America and to unions. To unions, it sent a message that you better be careful if you're militant, because bad things can happen. And to corporate America, it sent a message, a green light saying, "Hey folks, it's now fine to get tough on workers, get tough on unions, because if the president of the United States can do it, so can you."

Weaker unions, tougher management practices, greater competition from abroad, and let me add one other thing, Sometimes I talk about how in World War II, the son of the banker and the son of the steelworker would be in the trenches together. And they felt a solidarity, they respected each other. I think that carried over in the '50s and '60s -- if you were a CEO, you were not out to screw and squeeze badly the guys who were in the trenches with you. They knew workers more, related to them more, and corporate headquarters was often right next to the factory. So, you lived near these workers and saw them every day.

I submit that capitalism in the United States has changed. It used to be managerial capitalism where a lot of managers were kind of benevolent, and not too tough. Now we have financial capitalism, Wall Street capitalism, and the folks on Wall Street really put humongous pressure on CEOs to maximize profits, and that often translates to squeezing workers on wages, and on health coverage, and on pensions, and on days off, and this and that.

Now people go to business school, and their views of how to run a business and how to treat workers are much different from the guys who fought in the trenches alongside blue-collar guys, and they became managers. I think a lot of business executives just don't relate to average workers. They just see them, not so much as people, [but] as costs, and as cogs.

You talked about the air traffic controllers, and one of the things that you mention in the book that struck me is that ironically, in 1980, they had endorsed Reagan for president because they were angry with Jimmy Carter and deregulation. It's extraordinary.

I have several chapters about the rise of labor focusing on some of the key, crucial dramatic episodes, like this great strike in 1909 by immigrant female garment workers in New York that won a huge victory, a 52-hour week. One of the crazy things is, so many Americans take the 40-hour week for granted, but here are all these people fighting for the 52-hour week. And then I write about the Flint sit-down strike, where workers sat down in a GM plant in Flint, Michigan for seven weeks in the middle of winter [1936-37], often without much heat General Motors was vicious towards the union. It used to have spies, used to have thugs beat up people. Ford as well.

And that was the biggest, most important strike in the 20th century. It was a huge victory, and it enabled the unionization of what was then the world's largest company. I have a chapter about another huge famous strike, the 1968 Memphis sanitation worker strike. A huge victory for labor rights and civil rights.

That's the rise of labor. Then I write about the decline of labor. The air traffic controller strike was not labor's finest hour. They were one of the very few unions to endorse Ronald Reagan. And when Reagan won, they thought, "This is great. We picked a winner. We'll be able to get a great deal from him." So, they demanded huge wage increases, far more than other federal workers, and they wanted these huge wage increases while having their workweek cut from five days to four days.

Under regulations for the federal workforce that were developed by President Kennedy, presidents weren't allowed to even negotiate about wages with federal employees. So, the Reagan administration gave them a few extra percent, almost twice as much as other federal employees, but [the controllers union] said, "We want more." They were super militant, and they walked out and they did not talk with other union leaders, they did not ask their advice, they did not seek support. They kind of walked out on a limb, and Ronald Reagan was more than happy to cut it off to show who's boss.

I'm sorry to say, and I feel terrible for these workers, the air traffic controllers that got fired, but I don't think the union was acting as wisely as it should. It was an illegal strike, and if you're going to engage in an illegal strike, you better be damn sure you have a lot of public support. And they did almost nothing to get public support [or] support from other unions as well.

You mention in the book that insofar as the negative things that have happened to labor, sometimes the wounds have been self-inflicted, that we've done it to ourselves.

There are a lot of great things in labor history. There were these heroic strikes, they'd stand up to the Pinkertons, and they'd stand up to the thugs. They won major gains. But unfortunately there was a darker side of unions. There was way too much union corruption, especially in the 1950s with the Teamsters and the Longshoremen. We're sitting on 51st Street in Manhattan -- four blocks south of here this very well-known labor newspaper columnist was blinded. They threw acid in his eyes because he had written a negative column about the operating engineer's union.

So there was a lot of corruption, too much violence, too much discrimination against African American workers, Asian American workers, Hispanic workers.

I've had lots of arguments with people over the years about union corruption, and I say it's much less than it used to be in the 1950s and the 1960s. The federal government really did a good job cleaning it up, and I think a lot of union leaders realized we have to be cleaner. There have been recent problems with the UAW, unfortunately. And that's not good.

But I argue with people, saying, I don't think corruption in labor unions now is any worse than corruption in business or corruption in government. Seeing so much corruption in business and in government today, I'm almost ready to start saying there's less corruption in unions than there is in business and government, pound for pound. Unions, after discriminating against women, and African Americans, Asian Americans, they've really come around a long way. They realized, in many ways, the future of labor is female workers, workers of color, immigrant workers. And they're doing a much better job trying to unionize these workers.

Not just unionize them, but take something like the Fight for $15 [the campaign to raise the minimum wage to $15 an hour]. The Service Employees International Union [SEIU], which really underwrote and inspired the Fight for $15 said, "We have a big problem in the United States. We're not focusing enough on the low wage workers and the difficult lives they face, and we want to change the national discussion to focus on that." The SEIU was very big hearted, because it realized it's going to help a lot of workers who aren't union members, but it just said, "We're going to spend some serious money to mobilize fast food workers, to put pressure on legislators, to put pressure on governors, to put pressure on companies to raise the floor." Because the floor in the United States is very low.

I was a reporter for The New York Times in Paris for five years as the European economics correspondent. And fast food workers in Denmark average over $20 an hour while they make $7.00, $8.00 here. All these folks in Europe made fun of what they called McJobs. And the SEIU said, "We have to raise the floor." So, it really helped -- they estimate now 24 million workers have had their wages increased because of the Fight for $15.

I was the first reporter in the nation to write about it. The first strike was November 29th, 2012. I remember speaking to the organizing director who said, "Our goal is a $15 [an hour] wage." I said, "Are you out of your gourd? $15 when you have people making $7.25, $8.00? That's just pie in the sky."

So, here we are, less than seven years later. New York State, California, Maryland, Connecticut, New Jersey, Washington, DC, Massachusetts, Illinois have passed $15 minimum wages. And some red states, like Arkansas, have raised their minimum wages. Not to $15, but the Fight for $15 has really changed the conversation, has really had ripple effects across the nation. And it shows [what happens] when a union acts smart, uses its money wisely, and knows how to hit a chord. It really came up with an important and popular message that wages are too low. It could really make a huge difference in our nation.

The hotel worker's union had a big strike last fall against Marriott. And I interviewed several hotel workers who were on strike, and they said, "I got to do two jobs, I got to do three jobs, making $8.00 or $9.00 an hour just doesn't cut it. I can't raise my two kids." So, they came up with a slogan for the strike, "One job is not enough." And again, it caught on like wildfire. People realize there's something wrong if you live in the richest nation on earth, and you can't begin to support your family working one full-time job.

You tell this story about what your mother said to you, when you were in Wisconsin while [then Governor] Scott Walker was cracking down on the public sector unions.

My mother was born in the 1920s, she was a teenager during the Great Depression. I was in Madison, Wisconsin, covering the fight to defeat Scott Walker's big effort to weaken public sector unions, to gut their right to collective bargaining, and really make their health and pension plans worse. I was on the phone with my mother. She was 86 at the time. This was back in 2011. And she said, "When I was growing up, people used to say, 'Look at the good wages and benefits that people in a union have. I want to join a union.' Now people say, 'Look at the good wages and benefits that union members have. They're getting more than what I get. That's not fair. Let's take away some of what they have.'"

And I add in my book, "Her comments captured an unfortunate loss of solidarity among Americans, as well as a lamentable impulse not to lift each other up, but to take away from other workers who might have it a little better."

Which reminds me -- nowadays, a lot of corporations say, "We're a much wealthier nation than in the 1930s, when the union movement took off. Corporations treat their workers well, rely on us, we'll take care of you."

Don't tell that to many workers at Wal-Mart, or Amazon, or McDonald's. And in my book, I quote Martin Luther King Jr.'s response to this. He said, "The labor movement was the principle force that transformed misery and despair into hope and progress. Out of its bold struggles, economic and social reform gave birth to unemployment insurance, old age pensions, government relief to the destitute, and above all, new wage levels that meant not mere survival, but a tolerable life. The captains of industry did not need this transformation. They resisted it until they were overcome."

And that was not long after George Meany, then the head of the AFL-CIO, had jumped on A. Phillip Randolph [president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters] for daring to talk about the needs of African Americans in the labor force.

I'm not a professional historian, but I know how to get enough information to write a good historical story. And one thing I didn't realize: the great Samuel Gompers, who was the first president of the American Federation of Labor, and is famous for saying, "We want more, we want more schools, we want more education, we want more freedom, more time for our better selves," he was also extremely anti-Chinese. I didn't realize he was one of the main forces behind the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. So you learn some of the dark side of history.

But then you learn about people like the great A. Philip Randolph who people don't know nearly enough about, one of the great labor leaders of the 20th century. He was running a leftist socialist newspaper in Harlem, The Messenger. There was a union, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, which represented the porters on the Pullman cars, and every union president, every union official would get fired [by the Pullman company], would get punished. So, they came up with this great idea, let's hire a non-Pullman worker to head the union. And they hired Randolph.

He was a key figure in labor history and in civil rights history. He was the one who pushed President Roosevelt, President FDR, to agree to integrate munitions factories, arms factories. He got Harry Truman to integrate the armed forces.

Everyone thinks it was the great Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. who organized the 1963 March on Washington. It's little known that the person who really organized it was A. Philip Randolph, and it's also not known that the folks who really paid for it and underwrote it were the United Automobile Workers. It's also not known that a lot of the original money for Caesar Chavez and the founding of the United Farm Workers also came from the UAW, and the UAW, Walter Reuther, they were the great bright light of unions in the 1950s, 1960s, 1970s.

Reuther, one of my heroes, you describe as the builder of the middle class.

Reuther grew up in West Virginia, his father was active with the brewer's union. Actually, when Reuther was a little boy, he visited the great socialist leader Eugene Debs in prison. Debs was in prison for calling for resisting the draft during World War I. But Debs was another great, great leader. Former head of the railroad union.

Reuther went to work in the auto industry. It was miserably dangerous. He used to work 13, 14 hour shifts. He became very active with the UAW. He was a brilliant guy; he rose up very quickly in the union. He became its president by age of 30 or so. And he really took on General Motors after World War II. He held a huge strike, and after that strike, GM did not want another big fight with the UAW, so they reached this amazing landmark settlement in 1950. At the time, union contracts usually lasted just a year and then you had to haggle and hassle over finding a new contract.

And General Motors also had a very smart CEO, Charles Wilson, Engine Charlie Wilson, and he wanted to hugely expand GM because America was building the interstate highways, people were moving to the suburbs, and he saw there was going to be this huge demand for automobiles. He wanted to greatly expand GM's production capacity, but there was one thorn in his side. The UAW. So, he basically told Reuther, "Let's have a win-win deal." And Reuther was smart, and he knew that sometimes if you work with management, great things happen. So, they reached this landmark agreement -- at a time when most union agreements were one year, they reached a five year agreement that called for a 2% annual improvement in pay to keep up [productivity]. Productivity was improving steadily, so there was 2% for that. Plus they got raises of several percent beyond that, plus there were bonuses.

So, over a five-year period, real after-inflation pay rose 20%. And that contract probably did more than any other single thing to really create the American middle class. Because that contract covered several hundred thousands of people -- it was adopted in other automakers, then the steelworkers got a similar contract. And all these other unionized companies said, "We got to do something like that." And then all these non-union companies that were eager not to be unionized said, "If we're going to keep out unions, we have to be generous like GM."

This was the Treaty of Detroit.

Yes. Companies were profitable, but before the Treaty of Detroit, the companies were keeping a lot of the profits for themselves. But after the Treaty of Detroit, and Walter Reuther, companies were forced to share much more of their profits, and that really financed, underwrote the formation of the middle class, and thanks to unions, we have the world's largest and richest middle class.

And partly because of the decline of the unions in the past, two, three, four decades, we're seeing a decline in the middle class. It's not just the decline of unions, it's also we're competing far more than before with China and Bangladesh, and Mexico. And that unfortunately, and almost necessarily will tug down wages in the United States.

I wanted to ask you about another of my labor heroes, Frances Perkins.

I've been fascinated by three people in labor history. Clara Lemlich, who was a young woman in New York in the early 1900s. She grew up in the Ukraine, Jewish family. She wasn't allowed to go to school because she was Jewish. And there was a horrible pogrom not far away from where she lived, so her family moved to New York City.

She wanted to be a doctor but she only spoke Yiddish. And so, she went to work in a sweatshop, and she became a firebrand, was speaking on soapboxes, and she was the spark that ignited the largest strike by women in American history, the 1909 uprising of 20,000 female garment workers that won the 52-hour work week.

Walter Reuther, whom I talked about, was another figure who fascinated me. A. Philip Randolph, too. But also Frances Perkins. She was labor secretary under Franklin Roosevelt, the nation's first female cabinet member. And I argue in my book that Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal maybe should be called Frances Perkins' New Deal.

Frances Perkins went to Mount Holyoke College, she taught for a while at a fancy girl's school north of Chicago called Ferry Hall. And while in Chicago, she became very involved with Jane Addams and Hull House. She said, "I don't want to spend my life teaching rich young ladies. I want to help the poor, I want to help workers." And she went to work in Philadelphia for a group that helped a lot of young African American immigrant women who were being pushed into prostitution.

Then she went to Columbia, to go to graduate school here in New York. And she also got a job as the head of the New York office of the National Consumers League. The National Consumers League was really an anti-sweatshop organization, and people don't realize that back before the Civil War, it pushed to boycott goods, cotton and sugar, made by slave labor.

She was very pro-worker, and she was having tea at a friend's house on Washington Square North, on a Saturday afternoon [in 1911], and they hear some sirens, fire engines, and the butler says, "There's something going on over there." And Frances Perkins literally runs 200 yards over to the Triangle fire, the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, which was just east of Washington Square. She stood and literally watched the poor young women jumping out of the windows to their deaths. 143 people died in that fire.

That also really changed her life, and she was appointed to head an investigative commission about why this happened and what could be done to stop this from happening [again]. Governor Al Smith appointed her as a top labor official. Then a succeeding governor, someone named Franklin Delano Roosevelt, made her his state's labor commissioner. She was the highest paid female government official in the country at the time.

Roosevelt's elected president, and his wife Eleanor and the great Jane Addams are saying, "You should name Frances Perkins your Labor Secretary." And all these union leaders are sneering at the idea of naming a woman, and they say, "You should only name a union official." And Roosevelt said, "Only a small minority of workers are in unions. The great majority are not in unions. We have to fight for them, too." And so, FDR summoned Frances Perkins to his very nice townhouse on East 65th Street in Manhattan, to feel her out about becoming labor secretary.

She had real gumption. She went with a list saying, if you want me to be labor secretary, these are the things you have to agree to: a 40-hour work week, Social Security, prohibitions on child labor, overtime laws, unemployment insurance, welfare for laid-off workers. And he agreed to all this.

So, you look at some of the great achievements of the New Deal, it's Social Security, it's the 40 hour work week, it's the minimum wage and overtime, it's unemployment insurance, She was a great underrated American. I often say, maybe she's the woman who should be on the $20 bill.

I wanted to talk to you about politics. You write in the book that labor unions have done more than any other institution to mobilize average Americans to get involved in our democracy and elections. How so?

At their peak, unions had 20 million members. And they wanted to elect candidates who would help workers. How do you elect candidates? You talk to your fellow union members to say, you should vote for this person or that person. You knock on doors, you make phone calls. My father, served in World War II, he served in Japan, he got back and his first job is with the AFL-CIO. The great Sidney Hillman, head of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers, in 1946 was running something called the Committee on Political Education, which was the AFL-CIO's political arm, and they realized we have to mobilize workers, get union members to vote.

And that really carried forward. Studies show that union members learn to go to meetings with management and speak up. When they do collective bargaining they help think through strategies. They hold meetings where they discuss what should be said, what the talking points should be. They help organize protests. A lot of union members learn basic political skills, learn the importance of electing people who say we'll vote to raise the minimum wage, who will vote to have more for the Occupational Safety and Health Act.

Some people, some lawmakers are against those things. So I think unions have played a very important role in politics. I also say in the book that other than perhaps the military, unions have done more to bring together people of all races and religions to work together. I read about some unions nowadays, there are Caucasians and Africans Americans, and Bangladeshis, and Eritreans, and Puerto Ricans, and Dominicans. Unions are really a great, functioning melting pot that bring people together for a common cause.

But the problem that you also point out is that in the 2015-16 election cycle, business outspent labor 16 to 1, by 3.4 billion dollars to 213 million.

Michael, it kills me when I hear conservative commentators and corporations say, "Big labor, it's too big. It's too powerful." And then I say, look, business contributed $3.4 billion in 2016, labor, $213 million. And look at lobbying. Each year, in lobbying in Washington, corporations spend just under $3 billion dollars, which is 660 times as much as the $48 million spent by unions.

Why did Congress, when it was dominated by Republicans, rush to enact a one trillion dollar tax cut for corporations when corporations already had record profits, when Wall Street was already at record levels? Because they were dancing to the tune of corporate lobbyists and corporate donors. And you didn't see Congress rushing to raise the minimum wage, they didn't care much about what happened with workers.

I argue very strongly in the book that things are really badly askew. The playing field is tilted badly against workers, and we need to fix that by having a fairer campaign finance system so that the Koch brothers and Sheldon Adelson don't have a million times as much say as the average school teacher, or Wal-Mart worker, or truck driver, or steel worker.

And we need to make it easier for folks to unionize, but it'll be very hard to enact laws like that until we fix our very broken, campaign finance system. Because so many lawmakers feel indebted to the wealthy donors and corporations that played a huge role in electing them.

But you write that part of Trump's success was that American workers were so frustrated about stagnant wages, and factories going out of business and going to other countries. That a lot of his success was that he played to that. And of course, in reality, he has done just the opposite.

This wonderful New Deal coalition of white workers and black workers, and Hispanic workers, and women, they all pulled together. And the Democrats increasingly, I'm sorry to say, have turned their backs away from blue collar workers, and I say it's unfortunate that Hillary Clinton too often became the candidate of the professional class. One could probably say the same about John Kerry, that they [associated with] lawyers, and Wall Street investors, and Hollywood celebrities, and they weren't paying enough attention to blue-collar workers. And Trump saw that.

Bill Clinton, and Hillary to some degree, and Barack Obama to some degree, they were very for free trade. And corporations are pushing that free trade agenda very hard, but a lot of these trade agreements really gave short shrift to workers. And I think Barack Obama unfortunately did not see that sufficiently, nor did Bill Clinton or Hillary, and Trump saw how angry workers in the Midwest were.

I think Trump is a very clever man, but a humongous demagogue, and he went to Ohio and Wisconsin and Michigan and Pennsylvania, and said, "What's happening with trade is horrible, China's raping us. I'm going to stop the outflow of jobs. I'm going to stop factories from closing. I'm going to bring back all the jobs." And people ate this stuff up.

I was in industrial areas in Pennsylvania, interviewing some workers. And some said, "I love what he said, he's our guy. He's going to fight for us." I spoke to some other people who said, "I know he was kind of full of BS, but he cared about our issues and it's important for me to feel that we're electing someone who cares about our issues."

I write in my book that while Trump promised to be the American worker's best friend, he and his appointees have in action after action after action -- rolling back overtime rules, saying Wall Street firms no longer have to work in the best interest in handling workers' 401Ks, reducing the number of safety investigators -- one thing after another, have taken anti-worker actions. I think it shows what contempt some politicians have toward workers. And I submit that if worker power were much, much greater, no politician would be acting so contemptuously toward workers.

But are you finding now, to whomever you're speaking, or whatever you're observing, that the anti-labor things that he has done have galvanized labor in this country?

Michael, yes and no. He still has a lot of blue collar people who love him...

I just wrote this big article saying he's kind of this magician. 95% of his actions involving workers are anti-worker -- reducing safety inspectors, reducing enforcement on minimum wage violations, making it easier to give federal contracts to companies that violate sex discrimination laws, and racial discrimination laws, and overtime laws -- but the one thing he's doing that people are really paying attention to is he's fighting China on trade. And I think a lot of workers see that, and think, "Oh, Trump is our hero. He's really sticking it to China on trade." They don't focus on the other 95%.

I think informed people, people who don't watch Fox News get a better sense of how anti-worker he is. But it's like the magician holds one hand in the spotlight, saying, "Look at this! I'm fighting China, I'm fighting China," while in the dark, the other hand that no one sees is pounding on workers. And I quoted this list of 50, 60 anti-worker actions his administration has taken. It's really startling.

I think the one area involving labor and workers where he's made good on his promises is that he promised to fight hard on trade, and he has. But I argue that he's really screwed that up royally. I used to cover the State Department and diplomacy for The New York Times. And Diplomacy 101, if you're going against another power, whether it's Russia or China, you don't do it by yourself. You get your allies. You get Canada, you get the NATO countries, you get the European Union, you get Japan, you get Australia to line up alongside you to really maximize pressure on your antagonist.

Unfortunately, Trump has alienated Canada, he's badly alienated NATO, he's badly alienated the European Union, he's alienated Japan, he's angered Australia, so he's [alone] doing this one-on-one confrontation with China. That screws a lot of Americans, because China can focus its retaliation on American farmers, American industries, and on American consumers. When it focuses its retaliation on just us, it hurts. Whereas, if we're with the 28 countries of the European Union and Canada and Australia and Japan, it could not punish us in the same way.

So, not only has he reduced our leverage greatly by going it alone, but he's ensured that American consumers and farmers and workers and industries will be hurt much worse.

I say he's done good in pursuing his goal of fighting China on trade, because China has really broken a lot of trade rules. Its' been stealing trade secrets, its been demanding that American companies turn over their technologies. So, China has in ways been a bad actor. But if you're going to do this huge fight, you've got to do it smartly, you've got to do it with allies. Not like someone who's just, "I'm going to fight him and I'm tough and he's just going to kiss my ring, and then it'll all be over." It's not going well with China.

Are you finding that any of the Democratic candidates are offering much more than lip service to labor at this point?

I covered labor for The New York Times from 1995 to 2014. And every two years during a congressional election or a presidential election I'd go out to Wisconsin or Michigan or Pennsylvania or Ohio to write about labor and the campaign. And Bill Clinton, Barack Obama, they didn't talk that much about unions. But I really see it very different this year. Partly because there are 20 candidates, and so they're looking for every edge, and they know one way to get an edge is to talk to labor.

But I think it's far deeper than that. I think they see, and I think Tom Perez, the head of the DNC, is telling them this, too. They see we lost Wisconsin, we lost Michigan, we lost Pennsylvania. Those were all labor strongholds. In my book, I explain that Scott Walker, in trying to eviscerate unions, helped reduce union membership in Wisconsin by over 150,000 during the past decade. Trump won Wisconsin by 22,000. So, you can imagine if union membership were much higher, and unions communicated with more union members, mobilized more union members, maybe Trump would not have won Wisconsin.

Ditto in Michigan. The Republicans there passed several things, a right to work law, a law making it much harder for childcare workers and healthcare workers to unionize, plus the auto industry crisis really reduced union membership there by about 140,000 in the past 10 years. Donald Trump won Michigan by 11,000.

I argue that certainly voter suppression, voter ID laws, made a big difference in Wisconsin and Michigan. But I also think its been underappreciated the degree to which the decline of unions helped Trump to win and Hillary to lose in those states.

I think the Democratic candidates really see that. And they realize finally, finally it's time to try to do something serious to help unions. So it's not a surprise that Bernie Sanders put out a pro-union platform. But if you read it, and you know anything about what it would take to rebuild unions, it's a very smart plan. It takes what the AFL-CIO wants, and what the SEIU wants.

Beto O'Rourke, and Pete Buttigieg, they've also put out union plans . And you look at Elizabeth Warren's trade plan, it's really smart. It says for too long, our trade policy has been for corporations, by corporations, of corporations. And we got to change it so it's for workers, for consumers, and she really wants to use trade agreements to raise labor standards while far too often they've pulled down labor standards.

So I think the candidates get it. Is it just lip service or not? I think a lot of them are serious. They realize that for the good of the Democratic Party, for the good of maintaining a decent social safety net, for the good of protecting Social Security, for the good of protecting Medicare, it's important to have a strong union movement because it will help protect all those things.

We talked about Fight for $15. What are some of the other positive things that are happening for the American worker right now?

It's kind of this contradictory moment because the percentage of workers in unions is way down. But then there's all this good news for labor, all this encouraging stuff. Some is statistical. Earlier this week, Gallup came out with its annual survey saying that public approval of unions is the highest it's been in around 50 years, 64%. That's up from 48% about 10 years ago. That's a big, big increase.

There's this big study by some folks at MIT saying 50% of non-union, non-managerial workers would vote to join a union tomorrow if they could. That's up from around 32% twenty years ago. And the highest approval rate for unions is among people ages 18 to 34.

One of the most hopeful things I've seen is in our union is the number of young people who are so enthusiastic.

Yes. And so, that's promising. Other promising things, if you'd asked me two or three years ago, "How are unions doing?" I'd say, "Except for the Fight for $15, they're pretty dead in the water." Then all of a sudden, pow! We saw the West Virginia teacher strike, and the Oklahoma teacher strike, and the Arizona teacher strike. And these were humongous strikes. Tens of thousands of workers, they were on the front page of newspapers, they led the TV news. People saw, hey, unions are important. They can do great things. And one of the really good things about the teacher strikes is that it wasn't just hey, I want a 7% raise, I want a 15% raise. It's also that what's happening in our states is bad for our kids, it's bad for our schools, and we unions are fighting, not just for us but for the schools, for the kids.

One of the crazy things, and I write about this in the book, is in West Virginia and Oklahoma and Arizona, red, red, red states, in all three states there are big tax cuts for the rich, big tax cuts for corporations, tax cuts especially for fracking. And as a result of those tax cuts, their general budgets were frozen, including the education budget. So for year after year, the education budgets weren't going up. And I interviewed some teachers in Arizona. One from a Phoenix suburb said she hadn't gotten a raise in 10 years. I interviewed Noah Karvelis, this 23-year-old music teacher who was really one of the people who ignited the Arizona strike. He was being paid $32,000 a year. As a teacher.

He only makes a little more than fast food workers. I interviewed this teacher who said she works at McDonald's from 8:00 PM to midnight each night to make ends meet and support her daughter. And then she has to get up at 6:00 AM to teach.

So, the #RedForEd strikes were really promising, and people really saw the potential of unions. The Fight for $15 has been really promising. In our industry, journalism, Michael, there's been a huge surge of people in the digital media; Vox, Vice, Slate, Salon, Huffington Post, 20, 30 other websites. The New York Times has long been unionized, The Washington Post has long been unionized, but the two most anti-union newspapers in the country, the LA Times and the Chicago Tribune, have both unionized. There's been a huge unionization wave in adjunct professors and graduate students.

So, I think a lot of well-educated people see that we do much better banding together in unions than we do alone. It's not easy to go in to your boss and say, "The 2% raise you gave me isn't enough. I want 4%." It's much better for 100 people to go in and say, "That 2% raise really sucked. You're not being fair to us. Your company's profitable. You should really give us a bigger raise."

Hopeful?

Well, it's the most hopeful I've been in a while, and there's certainly much more energy. But I'm sorry to say, [you look at] the way corporations dominate campaign finance, the way the rich dominate so many elections, And you look at how they've bought so many of the state legislatures. You read Jane Mayer's great book, Dark Money, for instance. And this new book, Kochland. I realized the whole climate denial movement was created by these two guys, the Koch brothers, because they were worried that the fight against global warming, and against carbon emissions would hurt their industry.

They bought up some professors, and they bought up some think tanks, and those professors and think tanks started spewing out false things about global warming. They had their report, so then they could buy lawmakers to do the same thing. And it's the same thing regarding workers. All these people say, "Oh, raising the minimum wage is terrible for workers, terrible for workers, terrible for workers." The workers don't think so. Business does, but workers know that a higher minimum wage really helps them and their families.

The book is Beaten Down, Worked Up. And I highly recommend it. Steven Greenhouse, thank you.

Thanks very much, Michael. Great to be here.

Donald Trump’s attacks on democracy, justice, and a free press are escalating — putting everything we stand for at risk. We believe a better world is possible, but we can’t get there without your support. Common Dreams stands apart. We answer only to you — our readers, activists, and changemakers — not to billionaires or corporations. Our independence allows us to cover the vital stories that others won’t, spotlighting movements for peace, equality, and human rights. Right now, our work faces unprecedented challenges. Misinformation is spreading, journalists are under attack, and financial pressures are mounting. As a reader-supported, nonprofit newsroom, your support is crucial to keep this journalism alive. Whatever you can give — $10, $25, or $100 — helps us stay strong and responsive when the world needs us most. Together, we’ll continue to build the independent, courageous journalism our movement relies on. Thank you for being part of this community. |

This past Saturday was the annual Labor Day Parade in New York City. They don't have it on the actual holiday anymore - too many people are more interested in a long, late summer weekend in the mountains or at the beach.

And yet the parade itself is a grand celebration of unions, even if in recent experience, there are more people marching up Fifth Avenue than on the sidewalk watching.

In a nutshell, that's kind of the state of organized labor in America these days; enthusiasm among those of us who are members of unions, who enjoy the power of solidarity at the bargaining table and fiercely believe in the importance of labor when it comes to fighting economic inequity, versus a public that too often reacts with indifference or even outright hostility.

But that's changing. There are signs of encouragement that come from both a vivid history, despite calamities along the way, and the growing realization among people that especially in these days of Trump and a corporate America running roughshod over working men and women there's a vital need to come together in the name of self-preservation and resistance.

In the interest of full disclosure, I was president of an AFL-CIO union, the Writers Guild of America East, for ten years and currently serve on its council. I've seen firsthand the strength that organized people in a union can bring to bear against organized money and influence.

That's one reason it was a pleasure to sit down last week with Steven Greenhouse, author of the new book Beaten Down, Worked Up: The Past, Present and Future of American Labor. Washington Post columnist E.J. Dionne described it as "an excellent account of how important strong unions were in moving our nation toward greater economic and social justice, and how the decline has increased inequality, and unfairness." But there is hope in this book as well, evidence of renewed recognition of the nation's workers as a growing force to be reckoned with once again.

Greenhouse spent three decades at The New York Times, 19 of them as its labor and workplace correspondent. He published his first book, The Big Squeeze: Tough Times for the American Worker, in 2009 and now brings his expertise in workplace issues to a number of publications including The Times, and The Guardian, The American Prospect, Time magazine, and the Columbia Journalism Review.

Our conversation is below, edited in some places for clarity, and also can be heard via SoundCloud:

We're recording this just a couple of days after the Labor Day weekend and it strikes me that increasingly we have lost sight of the significance of that holiday. What has happened to American labor, and why are our citizens so ignorant of its history?

It is upsetting that so many Americans are ignorant about Labor Day and labor unions. One of the reasons my editor asked me to write the book was that there was a great concern that tens of millions of Americans know far too little about unions, far too little about labor, far too little about what unions have accomplished over the decades for American workers. They've really played a pivotal role in creating the middle class. I love the bumper sticker and it's really true, "Unions: The Folks who Brought You the Weekend."

I think in school nowadays, a lot of students don't learn anything about, or learn very little about unions. And I can only begin to imagine what anti-union states like Mississippi and Alabama teach about unions. There isn't enough coverage of average workers and what they face in the news media. There are some labor reporters on some of the vigorous new websites, like Huffington Post, and Vox. But the TV networks don't do enough, the radio networks don't do enough. There's lots of coverage about tariffs, and Wall Street, but very little about how tough it is for many millions of workers to make ends meet.

We keep hearing Donald Trump say, "I've made American great again. It's the best thing ever." Well, 40% of the American people can't afford to pay a $400 bill. So we have problems. And I wrote this book to really shine a light on the problems American workers face, and that's caused in part by the decline in unions. [But] I also write about what can be done to rebuild worker power to help create a fairer, more democratic America.

You've structured [the book] in a very interesting and I think highly readable way, by telling us stories of individuals from around the country and their struggles to make a living. Terrence Wise and his family are a good example. Can you tell me about them?

I was doing a radio interview and there's a fast food worker on from Kansas City, Terrence Wise. He says he works full-time at Burger King, and full-time at Pizza Hut. He and his family were homeless at the time because one of the fast food chains had cut his hours back, and his fiancee, a home care worker, had hurt her back badly. So, even though he was basically working two full-time jobs, he, his fiancee and their three daughters were homeless.

I interviewed him later in the day, and he told me he was once studying for the clergy, but he had to drop out of school because he couldn't make ends meet. So I went to Kansas City, I wrote a profile of him for The New York Times.

He said, "I'm a fast food worker, I push for a $15 wage. All these people come in and say, 'You should go to college. That's how you should raise your income. Don't protest for higher wages.'" And he said, "I'd love to go to college. I have three daughters. I just can't drop my job and go to college."

[Even] if all the fast food workers, and all the home care aides, and all the cleaners and janitors went to college to improve their education, to get higher wages, we're still going to need millions and millions of fast food workers and home care workers, cleaners, and janitors. And they should not be consigned to poverty wages of $7.25 an hour. Terrence Wise has a very eloquent story of working two full-time jobs; he would leave his home at 6:00 AM to head to the first job before his three daughters got up. He'd finish one job around 3:00, then he'd go to the other job, and often get home after midnight, after his daughters had gone to sleep. And his daughters were complaining, "Hey, dad, we never see you anymore."

How would a union change his life?

It would win him higher wages, it would perhaps mean improved staff -- he said that on a weekday normally, 12, 14 people work prime shifts at the restaurant. On Sundays, there are only four people who work. But on Sundays in Kansas City there often are big football games where millions of people mob downtown to go to the stadium. But there are just four people working. He says, "We work our tails off." And if there were union, that could help improve staffing levels, he might have to worry less if he ever complained about bad conditions, or a bullying boss. He won't have to worry so much about being arbitrarily fired for speaking out. Unions would help protect him.

You begin by laying out a great many disturbing facts and figures about the state of labor in this country, noting that the United States now has the weakest labor movement of any industrial nation -- and that too often, employers fail to show workers basic respect. What happened? What changed?

I covered labor and workplace matters in The New York Times for 19 years, a pretty good stretch of time -- 200, 300 stories a year. But over 19 years, you see trends, and during the late '90s and the first decade of the 2000s, I saw that... while corporations were getting record profits -- this was years before the big recession -- things were getting worse and worse for workers. Wages were stagnant, companies, though they had record profits, were cutting back on healthcare coverage, cutting back on pensions, just trying to maximize their profits and squeeze their workers.

You ask why this is happening. Unions have grown much weaker. They've gone from representing 35% of the workforce in the 1950s, to 25% in the 1980s, now down to just over 10%; in the private sector, just over 6%.

Unions help make sure that workers are treated with dignity and respect. You have a shop steward who will talk back to a bullying boss, trying to make sure they don't treat you like dirt.

Another big change, I believe, is this focus on profit maximization. I write in the book that during World War II, unions and management really worked hand in hand, working closely together because they had a common enemy, the Nazis, the Axis. And relations were pretty good between management and labor in the 1950s and 1960s, but fast forward to the1970s. The economy faced some real crises, the oil shocks, and in the 1980s we had a horrible recession, and a huge inflow of imports. So corporate America said, "Hey, we have really got to get tougher on workers. This cooperation in the '50s and '60s, that's not the way to go. We've got to increase our profits."

So, they got much tougher on workers, much tougher on labor unions, and in 1980, Ronald Regan was elected as a conservative. Former head of the Screen Actor's Guild, former union president, but there was an illegal strike in his first few months in office by the air traffic controllers, and he really cracked down very, very hard to show who's boss.

He fired 11,700 air traffic controllers, and that sent a strong message both to corporate America and to unions. To unions, it sent a message that you better be careful if you're militant, because bad things can happen. And to corporate America, it sent a message, a green light saying, "Hey folks, it's now fine to get tough on workers, get tough on unions, because if the president of the United States can do it, so can you."

Weaker unions, tougher management practices, greater competition from abroad, and let me add one other thing, Sometimes I talk about how in World War II, the son of the banker and the son of the steelworker would be in the trenches together. And they felt a solidarity, they respected each other. I think that carried over in the '50s and '60s -- if you were a CEO, you were not out to screw and squeeze badly the guys who were in the trenches with you. They knew workers more, related to them more, and corporate headquarters was often right next to the factory. So, you lived near these workers and saw them every day.

I submit that capitalism in the United States has changed. It used to be managerial capitalism where a lot of managers were kind of benevolent, and not too tough. Now we have financial capitalism, Wall Street capitalism, and the folks on Wall Street really put humongous pressure on CEOs to maximize profits, and that often translates to squeezing workers on wages, and on health coverage, and on pensions, and on days off, and this and that.

Now people go to business school, and their views of how to run a business and how to treat workers are much different from the guys who fought in the trenches alongside blue-collar guys, and they became managers. I think a lot of business executives just don't relate to average workers. They just see them, not so much as people, [but] as costs, and as cogs.

You talked about the air traffic controllers, and one of the things that you mention in the book that struck me is that ironically, in 1980, they had endorsed Reagan for president because they were angry with Jimmy Carter and deregulation. It's extraordinary.

I have several chapters about the rise of labor focusing on some of the key, crucial dramatic episodes, like this great strike in 1909 by immigrant female garment workers in New York that won a huge victory, a 52-hour week. One of the crazy things is, so many Americans take the 40-hour week for granted, but here are all these people fighting for the 52-hour week. And then I write about the Flint sit-down strike, where workers sat down in a GM plant in Flint, Michigan for seven weeks in the middle of winter [1936-37], often without much heat General Motors was vicious towards the union. It used to have spies, used to have thugs beat up people. Ford as well.

And that was the biggest, most important strike in the 20th century. It was a huge victory, and it enabled the unionization of what was then the world's largest company. I have a chapter about another huge famous strike, the 1968 Memphis sanitation worker strike. A huge victory for labor rights and civil rights.

That's the rise of labor. Then I write about the decline of labor. The air traffic controller strike was not labor's finest hour. They were one of the very few unions to endorse Ronald Reagan. And when Reagan won, they thought, "This is great. We picked a winner. We'll be able to get a great deal from him." So, they demanded huge wage increases, far more than other federal workers, and they wanted these huge wage increases while having their workweek cut from five days to four days.

Under regulations for the federal workforce that were developed by President Kennedy, presidents weren't allowed to even negotiate about wages with federal employees. So, the Reagan administration gave them a few extra percent, almost twice as much as other federal employees, but [the controllers union] said, "We want more." They were super militant, and they walked out and they did not talk with other union leaders, they did not ask their advice, they did not seek support. They kind of walked out on a limb, and Ronald Reagan was more than happy to cut it off to show who's boss.

I'm sorry to say, and I feel terrible for these workers, the air traffic controllers that got fired, but I don't think the union was acting as wisely as it should. It was an illegal strike, and if you're going to engage in an illegal strike, you better be damn sure you have a lot of public support. And they did almost nothing to get public support [or] support from other unions as well.

You mention in the book that insofar as the negative things that have happened to labor, sometimes the wounds have been self-inflicted, that we've done it to ourselves.

There are a lot of great things in labor history. There were these heroic strikes, they'd stand up to the Pinkertons, and they'd stand up to the thugs. They won major gains. But unfortunately there was a darker side of unions. There was way too much union corruption, especially in the 1950s with the Teamsters and the Longshoremen. We're sitting on 51st Street in Manhattan -- four blocks south of here this very well-known labor newspaper columnist was blinded. They threw acid in his eyes because he had written a negative column about the operating engineer's union.

So there was a lot of corruption, too much violence, too much discrimination against African American workers, Asian American workers, Hispanic workers.

I've had lots of arguments with people over the years about union corruption, and I say it's much less than it used to be in the 1950s and the 1960s. The federal government really did a good job cleaning it up, and I think a lot of union leaders realized we have to be cleaner. There have been recent problems with the UAW, unfortunately. And that's not good.

But I argue with people, saying, I don't think corruption in labor unions now is any worse than corruption in business or corruption in government. Seeing so much corruption in business and in government today, I'm almost ready to start saying there's less corruption in unions than there is in business and government, pound for pound. Unions, after discriminating against women, and African Americans, Asian Americans, they've really come around a long way. They realized, in many ways, the future of labor is female workers, workers of color, immigrant workers. And they're doing a much better job trying to unionize these workers.

Not just unionize them, but take something like the Fight for $15 [the campaign to raise the minimum wage to $15 an hour]. The Service Employees International Union [SEIU], which really underwrote and inspired the Fight for $15 said, "We have a big problem in the United States. We're not focusing enough on the low wage workers and the difficult lives they face, and we want to change the national discussion to focus on that." The SEIU was very big hearted, because it realized it's going to help a lot of workers who aren't union members, but it just said, "We're going to spend some serious money to mobilize fast food workers, to put pressure on legislators, to put pressure on governors, to put pressure on companies to raise the floor." Because the floor in the United States is very low.

I was a reporter for The New York Times in Paris for five years as the European economics correspondent. And fast food workers in Denmark average over $20 an hour while they make $7.00, $8.00 here. All these folks in Europe made fun of what they called McJobs. And the SEIU said, "We have to raise the floor." So, it really helped -- they estimate now 24 million workers have had their wages increased because of the Fight for $15.

I was the first reporter in the nation to write about it. The first strike was November 29th, 2012. I remember speaking to the organizing director who said, "Our goal is a $15 [an hour] wage." I said, "Are you out of your gourd? $15 when you have people making $7.25, $8.00? That's just pie in the sky."

So, here we are, less than seven years later. New York State, California, Maryland, Connecticut, New Jersey, Washington, DC, Massachusetts, Illinois have passed $15 minimum wages. And some red states, like Arkansas, have raised their minimum wages. Not to $15, but the Fight for $15 has really changed the conversation, has really had ripple effects across the nation. And it shows [what happens] when a union acts smart, uses its money wisely, and knows how to hit a chord. It really came up with an important and popular message that wages are too low. It could really make a huge difference in our nation.

The hotel worker's union had a big strike last fall against Marriott. And I interviewed several hotel workers who were on strike, and they said, "I got to do two jobs, I got to do three jobs, making $8.00 or $9.00 an hour just doesn't cut it. I can't raise my two kids." So, they came up with a slogan for the strike, "One job is not enough." And again, it caught on like wildfire. People realize there's something wrong if you live in the richest nation on earth, and you can't begin to support your family working one full-time job.

You tell this story about what your mother said to you, when you were in Wisconsin while [then Governor] Scott Walker was cracking down on the public sector unions.

My mother was born in the 1920s, she was a teenager during the Great Depression. I was in Madison, Wisconsin, covering the fight to defeat Scott Walker's big effort to weaken public sector unions, to gut their right to collective bargaining, and really make their health and pension plans worse. I was on the phone with my mother. She was 86 at the time. This was back in 2011. And she said, "When I was growing up, people used to say, 'Look at the good wages and benefits that people in a union have. I want to join a union.' Now people say, 'Look at the good wages and benefits that union members have. They're getting more than what I get. That's not fair. Let's take away some of what they have.'"

And I add in my book, "Her comments captured an unfortunate loss of solidarity among Americans, as well as a lamentable impulse not to lift each other up, but to take away from other workers who might have it a little better."

Which reminds me -- nowadays, a lot of corporations say, "We're a much wealthier nation than in the 1930s, when the union movement took off. Corporations treat their workers well, rely on us, we'll take care of you."

Don't tell that to many workers at Wal-Mart, or Amazon, or McDonald's. And in my book, I quote Martin Luther King Jr.'s response to this. He said, "The labor movement was the principle force that transformed misery and despair into hope and progress. Out of its bold struggles, economic and social reform gave birth to unemployment insurance, old age pensions, government relief to the destitute, and above all, new wage levels that meant not mere survival, but a tolerable life. The captains of industry did not need this transformation. They resisted it until they were overcome."

And that was not long after George Meany, then the head of the AFL-CIO, had jumped on A. Phillip Randolph [president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters] for daring to talk about the needs of African Americans in the labor force.

I'm not a professional historian, but I know how to get enough information to write a good historical story. And one thing I didn't realize: the great Samuel Gompers, who was the first president of the American Federation of Labor, and is famous for saying, "We want more, we want more schools, we want more education, we want more freedom, more time for our better selves," he was also extremely anti-Chinese. I didn't realize he was one of the main forces behind the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. So you learn some of the dark side of history.

But then you learn about people like the great A. Philip Randolph who people don't know nearly enough about, one of the great labor leaders of the 20th century. He was running a leftist socialist newspaper in Harlem, The Messenger. There was a union, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, which represented the porters on the Pullman cars, and every union president, every union official would get fired [by the Pullman company], would get punished. So, they came up with this great idea, let's hire a non-Pullman worker to head the union. And they hired Randolph.

He was a key figure in labor history and in civil rights history. He was the one who pushed President Roosevelt, President FDR, to agree to integrate munitions factories, arms factories. He got Harry Truman to integrate the armed forces.

Everyone thinks it was the great Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. who organized the 1963 March on Washington. It's little known that the person who really organized it was A. Philip Randolph, and it's also not known that the folks who really paid for it and underwrote it were the United Automobile Workers. It's also not known that a lot of the original money for Caesar Chavez and the founding of the United Farm Workers also came from the UAW, and the UAW, Walter Reuther, they were the great bright light of unions in the 1950s, 1960s, 1970s.

Reuther, one of my heroes, you describe as the builder of the middle class.

Reuther grew up in West Virginia, his father was active with the brewer's union. Actually, when Reuther was a little boy, he visited the great socialist leader Eugene Debs in prison. Debs was in prison for calling for resisting the draft during World War I. But Debs was another great, great leader. Former head of the railroad union.

Reuther went to work in the auto industry. It was miserably dangerous. He used to work 13, 14 hour shifts. He became very active with the UAW. He was a brilliant guy; he rose up very quickly in the union. He became its president by age of 30 or so. And he really took on General Motors after World War II. He held a huge strike, and after that strike, GM did not want another big fight with the UAW, so they reached this amazing landmark settlement in 1950. At the time, union contracts usually lasted just a year and then you had to haggle and hassle over finding a new contract.

And General Motors also had a very smart CEO, Charles Wilson, Engine Charlie Wilson, and he wanted to hugely expand GM because America was building the interstate highways, people were moving to the suburbs, and he saw there was going to be this huge demand for automobiles. He wanted to greatly expand GM's production capacity, but there was one thorn in his side. The UAW. So, he basically told Reuther, "Let's have a win-win deal." And Reuther was smart, and he knew that sometimes if you work with management, great things happen. So, they reached this landmark agreement -- at a time when most union agreements were one year, they reached a five year agreement that called for a 2% annual improvement in pay to keep up [productivity]. Productivity was improving steadily, so there was 2% for that. Plus they got raises of several percent beyond that, plus there were bonuses.

So, over a five-year period, real after-inflation pay rose 20%. And that contract probably did more than any other single thing to really create the American middle class. Because that contract covered several hundred thousands of people -- it was adopted in other automakers, then the steelworkers got a similar contract. And all these other unionized companies said, "We got to do something like that." And then all these non-union companies that were eager not to be unionized said, "If we're going to keep out unions, we have to be generous like GM."

This was the Treaty of Detroit.

Yes. Companies were profitable, but before the Treaty of Detroit, the companies were keeping a lot of the profits for themselves. But after the Treaty of Detroit, and Walter Reuther, companies were forced to share much more of their profits, and that really financed, underwrote the formation of the middle class, and thanks to unions, we have the world's largest and richest middle class.

And partly because of the decline of the unions in the past, two, three, four decades, we're seeing a decline in the middle class. It's not just the decline of unions, it's also we're competing far more than before with China and Bangladesh, and Mexico. And that unfortunately, and almost necessarily will tug down wages in the United States.

I wanted to ask you about another of my labor heroes, Frances Perkins.

I've been fascinated by three people in labor history. Clara Lemlich, who was a young woman in New York in the early 1900s. She grew up in the Ukraine, Jewish family. She wasn't allowed to go to school because she was Jewish. And there was a horrible pogrom not far away from where she lived, so her family moved to New York City.

She wanted to be a doctor but she only spoke Yiddish. And so, she went to work in a sweatshop, and she became a firebrand, was speaking on soapboxes, and she was the spark that ignited the largest strike by women in American history, the 1909 uprising of 20,000 female garment workers that won the 52-hour work week.

Walter Reuther, whom I talked about, was another figure who fascinated me. A. Philip Randolph, too. But also Frances Perkins. She was labor secretary under Franklin Roosevelt, the nation's first female cabinet member. And I argue in my book that Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal maybe should be called Frances Perkins' New Deal.

Frances Perkins went to Mount Holyoke College, she taught for a while at a fancy girl's school north of Chicago called Ferry Hall. And while in Chicago, she became very involved with Jane Addams and Hull House. She said, "I don't want to spend my life teaching rich young ladies. I want to help the poor, I want to help workers." And she went to work in Philadelphia for a group that helped a lot of young African American immigrant women who were being pushed into prostitution.

Then she went to Columbia, to go to graduate school here in New York. And she also got a job as the head of the New York office of the National Consumers League. The National Consumers League was really an anti-sweatshop organization, and people don't realize that back before the Civil War, it pushed to boycott goods, cotton and sugar, made by slave labor.

She was very pro-worker, and she was having tea at a friend's house on Washington Square North, on a Saturday afternoon [in 1911], and they hear some sirens, fire engines, and the butler says, "There's something going on over there." And Frances Perkins literally runs 200 yards over to the Triangle fire, the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, which was just east of Washington Square. She stood and literally watched the poor young women jumping out of the windows to their deaths. 143 people died in that fire.

That also really changed her life, and she was appointed to head an investigative commission about why this happened and what could be done to stop this from happening [again]. Governor Al Smith appointed her as a top labor official. Then a succeeding governor, someone named Franklin Delano Roosevelt, made her his state's labor commissioner. She was the highest paid female government official in the country at the time.

Roosevelt's elected president, and his wife Eleanor and the great Jane Addams are saying, "You should name Frances Perkins your Labor Secretary." And all these union leaders are sneering at the idea of naming a woman, and they say, "You should only name a union official." And Roosevelt said, "Only a small minority of workers are in unions. The great majority are not in unions. We have to fight for them, too." And so, FDR summoned Frances Perkins to his very nice townhouse on East 65th Street in Manhattan, to feel her out about becoming labor secretary.

She had real gumption. She went with a list saying, if you want me to be labor secretary, these are the things you have to agree to: a 40-hour work week, Social Security, prohibitions on child labor, overtime laws, unemployment insurance, welfare for laid-off workers. And he agreed to all this.

So, you look at some of the great achievements of the New Deal, it's Social Security, it's the 40 hour work week, it's the minimum wage and overtime, it's unemployment insurance, She was a great underrated American. I often say, maybe she's the woman who should be on the $20 bill.

I wanted to talk to you about politics. You write in the book that labor unions have done more than any other institution to mobilize average Americans to get involved in our democracy and elections. How so?

At their peak, unions had 20 million members. And they wanted to elect candidates who would help workers. How do you elect candidates? You talk to your fellow union members to say, you should vote for this person or that person. You knock on doors, you make phone calls. My father, served in World War II, he served in Japan, he got back and his first job is with the AFL-CIO. The great Sidney Hillman, head of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers, in 1946 was running something called the Committee on Political Education, which was the AFL-CIO's political arm, and they realized we have to mobilize workers, get union members to vote.