SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

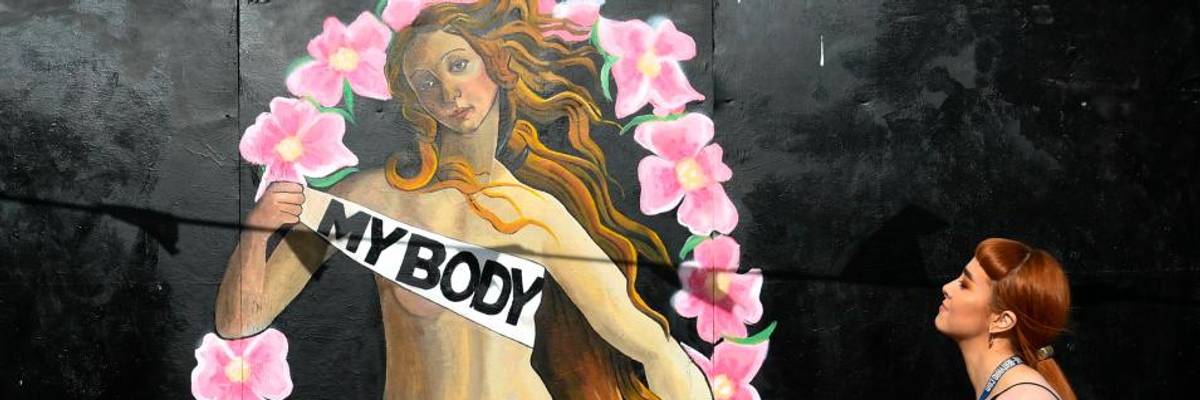

A woman walks in front of a pro-choice mural relating to the laws regarding abortion in Dublin on May 11, 2018 ahead of a national referendum (Photo: Artur Widak/AFP/Getty Images)

I have never said this publicly before, but in December 1974 I had an abortion.

I was 22 years old, living in a cold, dark house in Portland, Oregon, spending my days huddled in front of a wood stove trying to finish my undergraduate senior thesis. I did not want to have a baby. I didn't know what would come next in my life, but I knew it would not include raising a child. Until the moment the doctor told me I was pregnant -- we didn't have at-home tests in those days -- I'd always believed that, although it was perfectly ethical for other women to have abortions, I would never do so. In that electric instant, however, I knew that what I had believed about myself was wrong.

My boyfriend wanted to cheer me up. "Put on your coat," he said. "We're going somewhere." He was a kind guy and we'd bonded over a shared interest in all things mechanical. I'd fallen in love with him a couple of years before when he'd taught me how to replace the ball joints on an ancient Rambler station wagon. I was probably even more in love with his raucous Irish Catholic family, especially his mother, the family matriarch, who'd graduated from Portland State long after giving birth to the last of her own six children.

My boyfriend was sweet, but his emotional imagination was a bit limited. That particular day, his idea of cheering me up turned out to be a visit to a local plumbing store, where we took in the wonders of flexible cables and bin after bin of nicely made solid brass fittings. You won't be surprised to learn that the excursion left me inadequately cheered.

What he may have lacked in emotional skills, however, he more than made up for in moral sensitivity. Some years later, long after we'd split up and I'd begun my first serious relationship with a woman, I asked him why we'd never talked about the abortion. "I knew it had to be up to you," he explained, "and I know you usually try to give other people what they want. Once you'd decided, I didn't want to risk saying anything to change your mind." Unlike many men, including our current president, my boyfriend believed that decisions about my body were mine alone to make.

Not Bad Luck, But a Bit Sloppy

In some ways, I was lucky. For one thing, early pregnancy made me queasy, so I recognized what was going on soon enough to have a simple termination. That was a piece of luck because I hadn't menstruated for over a year, so I didn't figure it out the way most women do -- by missing my period.

My gynecologist misdiagnosed my failure to menstruate. He was so fascinated by the fact that one of my parents was of Ashkenazi Jewish descent that he never thought to ask me whether I'd been starving myself to achieve something vaguely approaching Twiggy-like thinness. Being underweight is a much more common cause of missing periods than genetic disease. He blamed my amenorrhea on an obscure condition that afflicts Jewish women with eastern European ancestry and then added, "But I don't understand it. You don't have any of the other symptoms." In any case, he told me that, if I ever wanted to conceive I would probably have to take medication. Or, as it turned out, gain a few pounds.

I was also lucky that it was 1974. Only the year before the Supreme Court had affirmed my right to end a pregnancy in its landmark Roe v. Waderuling. Overnight, the decision to have an abortion had become a private matter between my doctor and me. Even before Roe, Oregon was one of the few states that permitted abortion with only one restriction -- a 30-day residency requirement. As a college dormitory resident assistant, I'd already accompanied a fellow student to the clean, professional clinic in Portland for a pre-Roe abortion.

People in California weren't so lucky. My present partner who went to the University of California, Berkeley, recalls that her friends had to travel to Tijuana, Mexico, for abortions, where they knew no one, didn't speak the language, and could only hope that they wouldn't end up sick, injured, or infertile.

My doctor had privileges at that same Portland clinic and the arrangements were simple. I was less lucky, however, in that my private health insurance, like most then and now, did not cover an abortion. It cost $400 -- equivalent to somewhere between $2,078 and $2,175 in today's dollars. That was a lot of money for a couple of scholarship students to put together. Fortunately, we'd set aside some of what we'd made the previous summer painting houses for my boyfriend's father.

Why Am I Telling You This?

At this moment in the age of Trump, it's long past time for people like me to go public about our abortions. Efforts to deny women abortion access (not to mention contraception) have only accelerated as the president seeks to appease his right-wing Christian supporters.

I teach ethics to undergraduates. We often spend class time on issues of sexuality, pleasure, and consent, and by the end of the first class my students always know that I'm a lesbian. I have never, however, taught a class on abortion. In the past, I explained this to friends by saying that I didn't want some of my students, implicitly or explicitly, to call other students murderers.

But the truth is darker than that. I didn't want them calling me a murderer. Yet the reason I come out about my sexual orientation applies no less to the classroom discussions I should have (but haven't) had about abortion. I come out because I want all my students to encounter a professor who's not ashamed to be a lesbian. Over the years, quite a few LGBTQ+ students have told me how much they appreciated my intentional visibility, how helpful they found it as they were navigating their own budding sexual lives. I think, however, that it's no less useful for students who identify with the heterosexual majority to observe that a woman like me can be a professor.

If I can come out as a lesbian, why not as a person who's had an abortion, especially in this embattled time of ours? It's not that I think abortion is murder. I don't think that a zygote, an embryo, or even a fetus is a person. It's easy to get confused about this when opponents of women's autonomy call the throbbing of a millimeters-long collection of cells a "fetal heartbeat" and use its presence to prevent women six-weeks pregnant or less from securing an abortion. Because many women don't even know they're pregnant at six weeks -- I didn't -- "fetal heartbeat laws" effectively ban almost all abortions. By the end of June 2019, at least eight states (Arkansas, Georgia, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Dakota, and Ohio) had passed just such a law. So far, none of them has gone into effect. As Anna North and Catherine Kim of Vox report, "The North Dakota, Arkansas, Iowa, Kentucky, and Mississippi bans have been blocked by courts" and, on July 3rd, a federal court issued a temporary injunction on the Ohio law, while the case against it proceeds.

People advocating such fetal heartbeat laws carry with them an image of the developing fetus that reminds me of the seventeenth-century belief that each human sperm cell contains a "homunculus," a miniature human being, curled up inside it. That's not actually how a fetus develops. "It's a process -- the heart doesn't just pop up one day," as gynecologist Sara Imershein told Guardian reporter Adrian Horton recently. "It's not a little child that just appears and just grows larger."

Anti-choice types have introduced another piece of obfuscation with the expression "late-term abortion." The average full-term pregnancy lasts 40 weeks, as Dr. Jen Gunter, also a gynecologist, explained to Horton. Doctors only call pregnancies that last longer than 40 weeks "late-term." However, as Horton points out, "Anti-abortion activists twisted the phrase into a political construct understood to be any abortion after the 21st week, late in the second trimester." In reality, says Gunter of the actual medical definition of the term, "Nobody is doing late-term abortions -- it doesn't happen, but it's become a part of our lexicon now."

Smashing the Patriarchy?

There's another reason why it's easier these days to be a lesbian in public than a woman who has chosen to have an abortion. While the years since the 1973 Roe decision have seen a profound expansion of legal rights and social acceptance for LGBTQ+ people, the same decades have been marked by periodic sharp declines in access to abortion and a steady, fierce, sometimes even murderous increase in attacks on it and its providers by the evangelical right in particular. This is not, perhaps, as surprising as it might seem. Abortion rights actually present a much deeper challenge to the status quo than gay people marrying or becoming soldiers.

For years I've wondered why my gay leaders think the two things I most want in the world are to get married and join the Army. After decades of struggle and litigation, however, gay activists have, in fact, secured both these goals (though President Trump has done his best to keep trans people from serving openly in the military). Neither achievement, however, has proven much of a threat to the cultural or economic status quo.

What could be more American, after all, than joining the imperial forces? While Donald Trump's Fourth of July "Salute to America" hardly launched the conflation of patriotism and militarism, it certainly reminded us that, for many people, "America" and "military" are two words for the same thing. And what could be more American than marrying and creating another consumption unit -- a nuclear family household, complete with children (however conceived)? Nothing about these two life paths turns out to lie far from the mainstream.

Abortion, by contrast, seems to violate the natural order of things. Women are supposed to have children. That's what women do. That's who women are. It's one thing to be childless by misfortune, but deciding to end a pregnancy is another matter entirely. It cuts off a possible future. That's what the word "decide" means in Latin -- "to cut away."

What I have cut away from my life, both literally and figuratively, is the work of childbearing and childrearing, the two activities that continue to define womanhood in my own and probably most other cultures. And while I believe that this choice was right for me -- and was also my right -- all these years later, I'm still, as my boyfriend observed, sensitive to the judgment of others. As a woman who never bore children, I'm aware that I'm an outlier even among those who have had abortions, most of whom have or will have children.

Even now, I probably wouldn't have the courage to tell my story if it weren't for a young African-American woman named Renee Bracey Sherman. She happens to be the niece of good friends of mine, but more important, she is, as she calls herself, "the Beyonce of Abortion Storytelling." For nearly a decade now, she has been telling her own abortion story, training other women to tell theirs, and urging all of us to listen. Pinned to the top of her Twitter feed is this warm greeting: "Daily reminder: if you've had an abortion, you don't need forgiveness from anyone unless you want it. You did nothing wrong. You are loved."

You can't imagine the abuse, the death threats she's received, often from people claiming to know where she lives. "Someone sent me an email," she told the Association for Women's Rights in Development, saying "that they hoped that I would get sold into the sex trade and get raped over and over and over again and forced to give birth over and over and over again until I finally died from childbirth."

Renee sees her commitment to women's abortion rights as profoundly life affirming -- especially for black women who are the most likely among us to choose abortion and the most affected by its increasing unavailability. She is offended by the attempts of white anti-abortion legislators to coopt the Black Lives Matter movement, as for example when Missouri state representative Mike Moon introduced the "All Lives Matter Act" in 2015. (It would have outlawed abortion by defining human life as beginning at conception.) As John Eligon of the New York Times recently reported, even among black evangelicals, there is substantial suspicion of white anti-abortion activists who describe their work as rising from a concern for black lives:

"'Those who are most vocal about abortion and abortion laws are my white brothers and sisters, and yet many of them don't care about the plight of the poor, the plight of the immigrant, the plight of African-Americans,' said the Rev. Dr. Luke Bobo, a minister from Kansas City, Mo., who is vehemently opposed to abortion. 'My argument here is, let's think about the entire life span of the person.'"

Why Now?

Why write now about an abortion I had almost half a century ago? At my age, of course, I'll never need another one, so why even mention such a personal matter, let alone publicize it?

In the age of Donald Trump and Brett Kavanaugh, the answer seems all too clear to me. As we second-wave feminists insisted long ago, the personal is political. Struggles over who cleans the house and who has -- or doesn't have -- babies have deep implications for the distribution of power in a society. This remains true today, as state governments, national politicians, and the Trump administration ramp up their campaigns to harness or control women's fertility, whether to produce babies of a desired race (as Iowa Congressman Steve King has advocated) or to prevent others from being born (as the long history of forced sterilization of women of color and poor women illustrates).

We've been going backwards on abortion access for decades. Since 1976, the Hyde Amendment has denied abortion services to women who get their health care through the federal Medicaid program, or indeed to anyone whose health insurance is federally funded. (A few states, like California, opt to pick up the tab with state funds.) But even for women who can afford abortions, options have steadily dwindled, as states pass laws restricting the operations of abortion clinics. Women sometimes have to travel hundreds of miles for a termination. Only a single clinic in Missouri, for example, provides abortions today.

Worse yet, the appointment of Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court may well have cemented an anti-Roe majority there. But the Trump administration hasn't waited for a future Supreme Court decision to move against abortion. It has already reinstated both domestic and international "gag rules" that prohibit federal funding for any nonprofit or non-governmental agency that even mentions the existence of abortion as an option for pregnant women. In the case of that international gag rule, organizations receiving U.S. government funds are not only prevented from providing abortion services or referrals directly, but may not donate money from any source to other organizations that do. Most of these organizations provide many other health services for women from birth control to cancer and HIV treatment. Clearly, preserving the "right to life" doesn't apply to the lives of actual women in this country or the developing world.

So the current perilous state of reproductive liberty is part of why I'm talking about my abortion now. But there's another reason. When I spent time in Central America in the 1980s, I found that the first question women I met often asked me was "Cuantos hijos tiene?" -- "How many children do you have?" They assumed that a woman in her early thirties would have children and this was their (very reasonable) way of reaching out across a cultural divide, of looking for commonality with this gringa who'd landed in their community. I was always a little embarrassed that the answer was "none." I would respond, however, that, although I had no children of my own, I had a compromiso -- a commitment -- to making the world a better place for children everywhere.

I was certainly telling them the truth then -- and I hope my life since hasn't made a liar of me -- but at the time, in some secret part of myself, I also believed that my decision not to have children was a selfish one. There was too much I wanted to do in my own life to voluntarily take on the responsibility for the lives of dependent others. Now, though, as the horrors of climate change reveal themselves daily, I sometimes think that choosing not to bring another resource-devouring, fossil-fuel-burning, carbon-dioxide-emitting American into the world might actually have been the most unselfish thing I've ever done.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

I have never said this publicly before, but in December 1974 I had an abortion.

I was 22 years old, living in a cold, dark house in Portland, Oregon, spending my days huddled in front of a wood stove trying to finish my undergraduate senior thesis. I did not want to have a baby. I didn't know what would come next in my life, but I knew it would not include raising a child. Until the moment the doctor told me I was pregnant -- we didn't have at-home tests in those days -- I'd always believed that, although it was perfectly ethical for other women to have abortions, I would never do so. In that electric instant, however, I knew that what I had believed about myself was wrong.

My boyfriend wanted to cheer me up. "Put on your coat," he said. "We're going somewhere." He was a kind guy and we'd bonded over a shared interest in all things mechanical. I'd fallen in love with him a couple of years before when he'd taught me how to replace the ball joints on an ancient Rambler station wagon. I was probably even more in love with his raucous Irish Catholic family, especially his mother, the family matriarch, who'd graduated from Portland State long after giving birth to the last of her own six children.

My boyfriend was sweet, but his emotional imagination was a bit limited. That particular day, his idea of cheering me up turned out to be a visit to a local plumbing store, where we took in the wonders of flexible cables and bin after bin of nicely made solid brass fittings. You won't be surprised to learn that the excursion left me inadequately cheered.

What he may have lacked in emotional skills, however, he more than made up for in moral sensitivity. Some years later, long after we'd split up and I'd begun my first serious relationship with a woman, I asked him why we'd never talked about the abortion. "I knew it had to be up to you," he explained, "and I know you usually try to give other people what they want. Once you'd decided, I didn't want to risk saying anything to change your mind." Unlike many men, including our current president, my boyfriend believed that decisions about my body were mine alone to make.

Not Bad Luck, But a Bit Sloppy

In some ways, I was lucky. For one thing, early pregnancy made me queasy, so I recognized what was going on soon enough to have a simple termination. That was a piece of luck because I hadn't menstruated for over a year, so I didn't figure it out the way most women do -- by missing my period.

My gynecologist misdiagnosed my failure to menstruate. He was so fascinated by the fact that one of my parents was of Ashkenazi Jewish descent that he never thought to ask me whether I'd been starving myself to achieve something vaguely approaching Twiggy-like thinness. Being underweight is a much more common cause of missing periods than genetic disease. He blamed my amenorrhea on an obscure condition that afflicts Jewish women with eastern European ancestry and then added, "But I don't understand it. You don't have any of the other symptoms." In any case, he told me that, if I ever wanted to conceive I would probably have to take medication. Or, as it turned out, gain a few pounds.

I was also lucky that it was 1974. Only the year before the Supreme Court had affirmed my right to end a pregnancy in its landmark Roe v. Waderuling. Overnight, the decision to have an abortion had become a private matter between my doctor and me. Even before Roe, Oregon was one of the few states that permitted abortion with only one restriction -- a 30-day residency requirement. As a college dormitory resident assistant, I'd already accompanied a fellow student to the clean, professional clinic in Portland for a pre-Roe abortion.

People in California weren't so lucky. My present partner who went to the University of California, Berkeley, recalls that her friends had to travel to Tijuana, Mexico, for abortions, where they knew no one, didn't speak the language, and could only hope that they wouldn't end up sick, injured, or infertile.

My doctor had privileges at that same Portland clinic and the arrangements were simple. I was less lucky, however, in that my private health insurance, like most then and now, did not cover an abortion. It cost $400 -- equivalent to somewhere between $2,078 and $2,175 in today's dollars. That was a lot of money for a couple of scholarship students to put together. Fortunately, we'd set aside some of what we'd made the previous summer painting houses for my boyfriend's father.

Why Am I Telling You This?

At this moment in the age of Trump, it's long past time for people like me to go public about our abortions. Efforts to deny women abortion access (not to mention contraception) have only accelerated as the president seeks to appease his right-wing Christian supporters.

I teach ethics to undergraduates. We often spend class time on issues of sexuality, pleasure, and consent, and by the end of the first class my students always know that I'm a lesbian. I have never, however, taught a class on abortion. In the past, I explained this to friends by saying that I didn't want some of my students, implicitly or explicitly, to call other students murderers.

But the truth is darker than that. I didn't want them calling me a murderer. Yet the reason I come out about my sexual orientation applies no less to the classroom discussions I should have (but haven't) had about abortion. I come out because I want all my students to encounter a professor who's not ashamed to be a lesbian. Over the years, quite a few LGBTQ+ students have told me how much they appreciated my intentional visibility, how helpful they found it as they were navigating their own budding sexual lives. I think, however, that it's no less useful for students who identify with the heterosexual majority to observe that a woman like me can be a professor.

If I can come out as a lesbian, why not as a person who's had an abortion, especially in this embattled time of ours? It's not that I think abortion is murder. I don't think that a zygote, an embryo, or even a fetus is a person. It's easy to get confused about this when opponents of women's autonomy call the throbbing of a millimeters-long collection of cells a "fetal heartbeat" and use its presence to prevent women six-weeks pregnant or less from securing an abortion. Because many women don't even know they're pregnant at six weeks -- I didn't -- "fetal heartbeat laws" effectively ban almost all abortions. By the end of June 2019, at least eight states (Arkansas, Georgia, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Dakota, and Ohio) had passed just such a law. So far, none of them has gone into effect. As Anna North and Catherine Kim of Vox report, "The North Dakota, Arkansas, Iowa, Kentucky, and Mississippi bans have been blocked by courts" and, on July 3rd, a federal court issued a temporary injunction on the Ohio law, while the case against it proceeds.

People advocating such fetal heartbeat laws carry with them an image of the developing fetus that reminds me of the seventeenth-century belief that each human sperm cell contains a "homunculus," a miniature human being, curled up inside it. That's not actually how a fetus develops. "It's a process -- the heart doesn't just pop up one day," as gynecologist Sara Imershein told Guardian reporter Adrian Horton recently. "It's not a little child that just appears and just grows larger."

Anti-choice types have introduced another piece of obfuscation with the expression "late-term abortion." The average full-term pregnancy lasts 40 weeks, as Dr. Jen Gunter, also a gynecologist, explained to Horton. Doctors only call pregnancies that last longer than 40 weeks "late-term." However, as Horton points out, "Anti-abortion activists twisted the phrase into a political construct understood to be any abortion after the 21st week, late in the second trimester." In reality, says Gunter of the actual medical definition of the term, "Nobody is doing late-term abortions -- it doesn't happen, but it's become a part of our lexicon now."

Smashing the Patriarchy?

There's another reason why it's easier these days to be a lesbian in public than a woman who has chosen to have an abortion. While the years since the 1973 Roe decision have seen a profound expansion of legal rights and social acceptance for LGBTQ+ people, the same decades have been marked by periodic sharp declines in access to abortion and a steady, fierce, sometimes even murderous increase in attacks on it and its providers by the evangelical right in particular. This is not, perhaps, as surprising as it might seem. Abortion rights actually present a much deeper challenge to the status quo than gay people marrying or becoming soldiers.

For years I've wondered why my gay leaders think the two things I most want in the world are to get married and join the Army. After decades of struggle and litigation, however, gay activists have, in fact, secured both these goals (though President Trump has done his best to keep trans people from serving openly in the military). Neither achievement, however, has proven much of a threat to the cultural or economic status quo.

What could be more American, after all, than joining the imperial forces? While Donald Trump's Fourth of July "Salute to America" hardly launched the conflation of patriotism and militarism, it certainly reminded us that, for many people, "America" and "military" are two words for the same thing. And what could be more American than marrying and creating another consumption unit -- a nuclear family household, complete with children (however conceived)? Nothing about these two life paths turns out to lie far from the mainstream.

Abortion, by contrast, seems to violate the natural order of things. Women are supposed to have children. That's what women do. That's who women are. It's one thing to be childless by misfortune, but deciding to end a pregnancy is another matter entirely. It cuts off a possible future. That's what the word "decide" means in Latin -- "to cut away."

What I have cut away from my life, both literally and figuratively, is the work of childbearing and childrearing, the two activities that continue to define womanhood in my own and probably most other cultures. And while I believe that this choice was right for me -- and was also my right -- all these years later, I'm still, as my boyfriend observed, sensitive to the judgment of others. As a woman who never bore children, I'm aware that I'm an outlier even among those who have had abortions, most of whom have or will have children.

Even now, I probably wouldn't have the courage to tell my story if it weren't for a young African-American woman named Renee Bracey Sherman. She happens to be the niece of good friends of mine, but more important, she is, as she calls herself, "the Beyonce of Abortion Storytelling." For nearly a decade now, she has been telling her own abortion story, training other women to tell theirs, and urging all of us to listen. Pinned to the top of her Twitter feed is this warm greeting: "Daily reminder: if you've had an abortion, you don't need forgiveness from anyone unless you want it. You did nothing wrong. You are loved."

You can't imagine the abuse, the death threats she's received, often from people claiming to know where she lives. "Someone sent me an email," she told the Association for Women's Rights in Development, saying "that they hoped that I would get sold into the sex trade and get raped over and over and over again and forced to give birth over and over and over again until I finally died from childbirth."

Renee sees her commitment to women's abortion rights as profoundly life affirming -- especially for black women who are the most likely among us to choose abortion and the most affected by its increasing unavailability. She is offended by the attempts of white anti-abortion legislators to coopt the Black Lives Matter movement, as for example when Missouri state representative Mike Moon introduced the "All Lives Matter Act" in 2015. (It would have outlawed abortion by defining human life as beginning at conception.) As John Eligon of the New York Times recently reported, even among black evangelicals, there is substantial suspicion of white anti-abortion activists who describe their work as rising from a concern for black lives:

"'Those who are most vocal about abortion and abortion laws are my white brothers and sisters, and yet many of them don't care about the plight of the poor, the plight of the immigrant, the plight of African-Americans,' said the Rev. Dr. Luke Bobo, a minister from Kansas City, Mo., who is vehemently opposed to abortion. 'My argument here is, let's think about the entire life span of the person.'"

Why Now?

Why write now about an abortion I had almost half a century ago? At my age, of course, I'll never need another one, so why even mention such a personal matter, let alone publicize it?

In the age of Donald Trump and Brett Kavanaugh, the answer seems all too clear to me. As we second-wave feminists insisted long ago, the personal is political. Struggles over who cleans the house and who has -- or doesn't have -- babies have deep implications for the distribution of power in a society. This remains true today, as state governments, national politicians, and the Trump administration ramp up their campaigns to harness or control women's fertility, whether to produce babies of a desired race (as Iowa Congressman Steve King has advocated) or to prevent others from being born (as the long history of forced sterilization of women of color and poor women illustrates).

We've been going backwards on abortion access for decades. Since 1976, the Hyde Amendment has denied abortion services to women who get their health care through the federal Medicaid program, or indeed to anyone whose health insurance is federally funded. (A few states, like California, opt to pick up the tab with state funds.) But even for women who can afford abortions, options have steadily dwindled, as states pass laws restricting the operations of abortion clinics. Women sometimes have to travel hundreds of miles for a termination. Only a single clinic in Missouri, for example, provides abortions today.

Worse yet, the appointment of Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court may well have cemented an anti-Roe majority there. But the Trump administration hasn't waited for a future Supreme Court decision to move against abortion. It has already reinstated both domestic and international "gag rules" that prohibit federal funding for any nonprofit or non-governmental agency that even mentions the existence of abortion as an option for pregnant women. In the case of that international gag rule, organizations receiving U.S. government funds are not only prevented from providing abortion services or referrals directly, but may not donate money from any source to other organizations that do. Most of these organizations provide many other health services for women from birth control to cancer and HIV treatment. Clearly, preserving the "right to life" doesn't apply to the lives of actual women in this country or the developing world.

So the current perilous state of reproductive liberty is part of why I'm talking about my abortion now. But there's another reason. When I spent time in Central America in the 1980s, I found that the first question women I met often asked me was "Cuantos hijos tiene?" -- "How many children do you have?" They assumed that a woman in her early thirties would have children and this was their (very reasonable) way of reaching out across a cultural divide, of looking for commonality with this gringa who'd landed in their community. I was always a little embarrassed that the answer was "none." I would respond, however, that, although I had no children of my own, I had a compromiso -- a commitment -- to making the world a better place for children everywhere.

I was certainly telling them the truth then -- and I hope my life since hasn't made a liar of me -- but at the time, in some secret part of myself, I also believed that my decision not to have children was a selfish one. There was too much I wanted to do in my own life to voluntarily take on the responsibility for the lives of dependent others. Now, though, as the horrors of climate change reveal themselves daily, I sometimes think that choosing not to bring another resource-devouring, fossil-fuel-burning, carbon-dioxide-emitting American into the world might actually have been the most unselfish thing I've ever done.

I have never said this publicly before, but in December 1974 I had an abortion.

I was 22 years old, living in a cold, dark house in Portland, Oregon, spending my days huddled in front of a wood stove trying to finish my undergraduate senior thesis. I did not want to have a baby. I didn't know what would come next in my life, but I knew it would not include raising a child. Until the moment the doctor told me I was pregnant -- we didn't have at-home tests in those days -- I'd always believed that, although it was perfectly ethical for other women to have abortions, I would never do so. In that electric instant, however, I knew that what I had believed about myself was wrong.

My boyfriend wanted to cheer me up. "Put on your coat," he said. "We're going somewhere." He was a kind guy and we'd bonded over a shared interest in all things mechanical. I'd fallen in love with him a couple of years before when he'd taught me how to replace the ball joints on an ancient Rambler station wagon. I was probably even more in love with his raucous Irish Catholic family, especially his mother, the family matriarch, who'd graduated from Portland State long after giving birth to the last of her own six children.

My boyfriend was sweet, but his emotional imagination was a bit limited. That particular day, his idea of cheering me up turned out to be a visit to a local plumbing store, where we took in the wonders of flexible cables and bin after bin of nicely made solid brass fittings. You won't be surprised to learn that the excursion left me inadequately cheered.

What he may have lacked in emotional skills, however, he more than made up for in moral sensitivity. Some years later, long after we'd split up and I'd begun my first serious relationship with a woman, I asked him why we'd never talked about the abortion. "I knew it had to be up to you," he explained, "and I know you usually try to give other people what they want. Once you'd decided, I didn't want to risk saying anything to change your mind." Unlike many men, including our current president, my boyfriend believed that decisions about my body were mine alone to make.

Not Bad Luck, But a Bit Sloppy

In some ways, I was lucky. For one thing, early pregnancy made me queasy, so I recognized what was going on soon enough to have a simple termination. That was a piece of luck because I hadn't menstruated for over a year, so I didn't figure it out the way most women do -- by missing my period.

My gynecologist misdiagnosed my failure to menstruate. He was so fascinated by the fact that one of my parents was of Ashkenazi Jewish descent that he never thought to ask me whether I'd been starving myself to achieve something vaguely approaching Twiggy-like thinness. Being underweight is a much more common cause of missing periods than genetic disease. He blamed my amenorrhea on an obscure condition that afflicts Jewish women with eastern European ancestry and then added, "But I don't understand it. You don't have any of the other symptoms." In any case, he told me that, if I ever wanted to conceive I would probably have to take medication. Or, as it turned out, gain a few pounds.

I was also lucky that it was 1974. Only the year before the Supreme Court had affirmed my right to end a pregnancy in its landmark Roe v. Waderuling. Overnight, the decision to have an abortion had become a private matter between my doctor and me. Even before Roe, Oregon was one of the few states that permitted abortion with only one restriction -- a 30-day residency requirement. As a college dormitory resident assistant, I'd already accompanied a fellow student to the clean, professional clinic in Portland for a pre-Roe abortion.

People in California weren't so lucky. My present partner who went to the University of California, Berkeley, recalls that her friends had to travel to Tijuana, Mexico, for abortions, where they knew no one, didn't speak the language, and could only hope that they wouldn't end up sick, injured, or infertile.

My doctor had privileges at that same Portland clinic and the arrangements were simple. I was less lucky, however, in that my private health insurance, like most then and now, did not cover an abortion. It cost $400 -- equivalent to somewhere between $2,078 and $2,175 in today's dollars. That was a lot of money for a couple of scholarship students to put together. Fortunately, we'd set aside some of what we'd made the previous summer painting houses for my boyfriend's father.

Why Am I Telling You This?

At this moment in the age of Trump, it's long past time for people like me to go public about our abortions. Efforts to deny women abortion access (not to mention contraception) have only accelerated as the president seeks to appease his right-wing Christian supporters.

I teach ethics to undergraduates. We often spend class time on issues of sexuality, pleasure, and consent, and by the end of the first class my students always know that I'm a lesbian. I have never, however, taught a class on abortion. In the past, I explained this to friends by saying that I didn't want some of my students, implicitly or explicitly, to call other students murderers.

But the truth is darker than that. I didn't want them calling me a murderer. Yet the reason I come out about my sexual orientation applies no less to the classroom discussions I should have (but haven't) had about abortion. I come out because I want all my students to encounter a professor who's not ashamed to be a lesbian. Over the years, quite a few LGBTQ+ students have told me how much they appreciated my intentional visibility, how helpful they found it as they were navigating their own budding sexual lives. I think, however, that it's no less useful for students who identify with the heterosexual majority to observe that a woman like me can be a professor.

If I can come out as a lesbian, why not as a person who's had an abortion, especially in this embattled time of ours? It's not that I think abortion is murder. I don't think that a zygote, an embryo, or even a fetus is a person. It's easy to get confused about this when opponents of women's autonomy call the throbbing of a millimeters-long collection of cells a "fetal heartbeat" and use its presence to prevent women six-weeks pregnant or less from securing an abortion. Because many women don't even know they're pregnant at six weeks -- I didn't -- "fetal heartbeat laws" effectively ban almost all abortions. By the end of June 2019, at least eight states (Arkansas, Georgia, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Dakota, and Ohio) had passed just such a law. So far, none of them has gone into effect. As Anna North and Catherine Kim of Vox report, "The North Dakota, Arkansas, Iowa, Kentucky, and Mississippi bans have been blocked by courts" and, on July 3rd, a federal court issued a temporary injunction on the Ohio law, while the case against it proceeds.

People advocating such fetal heartbeat laws carry with them an image of the developing fetus that reminds me of the seventeenth-century belief that each human sperm cell contains a "homunculus," a miniature human being, curled up inside it. That's not actually how a fetus develops. "It's a process -- the heart doesn't just pop up one day," as gynecologist Sara Imershein told Guardian reporter Adrian Horton recently. "It's not a little child that just appears and just grows larger."

Anti-choice types have introduced another piece of obfuscation with the expression "late-term abortion." The average full-term pregnancy lasts 40 weeks, as Dr. Jen Gunter, also a gynecologist, explained to Horton. Doctors only call pregnancies that last longer than 40 weeks "late-term." However, as Horton points out, "Anti-abortion activists twisted the phrase into a political construct understood to be any abortion after the 21st week, late in the second trimester." In reality, says Gunter of the actual medical definition of the term, "Nobody is doing late-term abortions -- it doesn't happen, but it's become a part of our lexicon now."

Smashing the Patriarchy?

There's another reason why it's easier these days to be a lesbian in public than a woman who has chosen to have an abortion. While the years since the 1973 Roe decision have seen a profound expansion of legal rights and social acceptance for LGBTQ+ people, the same decades have been marked by periodic sharp declines in access to abortion and a steady, fierce, sometimes even murderous increase in attacks on it and its providers by the evangelical right in particular. This is not, perhaps, as surprising as it might seem. Abortion rights actually present a much deeper challenge to the status quo than gay people marrying or becoming soldiers.

For years I've wondered why my gay leaders think the two things I most want in the world are to get married and join the Army. After decades of struggle and litigation, however, gay activists have, in fact, secured both these goals (though President Trump has done his best to keep trans people from serving openly in the military). Neither achievement, however, has proven much of a threat to the cultural or economic status quo.

What could be more American, after all, than joining the imperial forces? While Donald Trump's Fourth of July "Salute to America" hardly launched the conflation of patriotism and militarism, it certainly reminded us that, for many people, "America" and "military" are two words for the same thing. And what could be more American than marrying and creating another consumption unit -- a nuclear family household, complete with children (however conceived)? Nothing about these two life paths turns out to lie far from the mainstream.

Abortion, by contrast, seems to violate the natural order of things. Women are supposed to have children. That's what women do. That's who women are. It's one thing to be childless by misfortune, but deciding to end a pregnancy is another matter entirely. It cuts off a possible future. That's what the word "decide" means in Latin -- "to cut away."

What I have cut away from my life, both literally and figuratively, is the work of childbearing and childrearing, the two activities that continue to define womanhood in my own and probably most other cultures. And while I believe that this choice was right for me -- and was also my right -- all these years later, I'm still, as my boyfriend observed, sensitive to the judgment of others. As a woman who never bore children, I'm aware that I'm an outlier even among those who have had abortions, most of whom have or will have children.

Even now, I probably wouldn't have the courage to tell my story if it weren't for a young African-American woman named Renee Bracey Sherman. She happens to be the niece of good friends of mine, but more important, she is, as she calls herself, "the Beyonce of Abortion Storytelling." For nearly a decade now, she has been telling her own abortion story, training other women to tell theirs, and urging all of us to listen. Pinned to the top of her Twitter feed is this warm greeting: "Daily reminder: if you've had an abortion, you don't need forgiveness from anyone unless you want it. You did nothing wrong. You are loved."

You can't imagine the abuse, the death threats she's received, often from people claiming to know where she lives. "Someone sent me an email," she told the Association for Women's Rights in Development, saying "that they hoped that I would get sold into the sex trade and get raped over and over and over again and forced to give birth over and over and over again until I finally died from childbirth."

Renee sees her commitment to women's abortion rights as profoundly life affirming -- especially for black women who are the most likely among us to choose abortion and the most affected by its increasing unavailability. She is offended by the attempts of white anti-abortion legislators to coopt the Black Lives Matter movement, as for example when Missouri state representative Mike Moon introduced the "All Lives Matter Act" in 2015. (It would have outlawed abortion by defining human life as beginning at conception.) As John Eligon of the New York Times recently reported, even among black evangelicals, there is substantial suspicion of white anti-abortion activists who describe their work as rising from a concern for black lives:

"'Those who are most vocal about abortion and abortion laws are my white brothers and sisters, and yet many of them don't care about the plight of the poor, the plight of the immigrant, the plight of African-Americans,' said the Rev. Dr. Luke Bobo, a minister from Kansas City, Mo., who is vehemently opposed to abortion. 'My argument here is, let's think about the entire life span of the person.'"

Why Now?

Why write now about an abortion I had almost half a century ago? At my age, of course, I'll never need another one, so why even mention such a personal matter, let alone publicize it?

In the age of Donald Trump and Brett Kavanaugh, the answer seems all too clear to me. As we second-wave feminists insisted long ago, the personal is political. Struggles over who cleans the house and who has -- or doesn't have -- babies have deep implications for the distribution of power in a society. This remains true today, as state governments, national politicians, and the Trump administration ramp up their campaigns to harness or control women's fertility, whether to produce babies of a desired race (as Iowa Congressman Steve King has advocated) or to prevent others from being born (as the long history of forced sterilization of women of color and poor women illustrates).

We've been going backwards on abortion access for decades. Since 1976, the Hyde Amendment has denied abortion services to women who get their health care through the federal Medicaid program, or indeed to anyone whose health insurance is federally funded. (A few states, like California, opt to pick up the tab with state funds.) But even for women who can afford abortions, options have steadily dwindled, as states pass laws restricting the operations of abortion clinics. Women sometimes have to travel hundreds of miles for a termination. Only a single clinic in Missouri, for example, provides abortions today.

Worse yet, the appointment of Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court may well have cemented an anti-Roe majority there. But the Trump administration hasn't waited for a future Supreme Court decision to move against abortion. It has already reinstated both domestic and international "gag rules" that prohibit federal funding for any nonprofit or non-governmental agency that even mentions the existence of abortion as an option for pregnant women. In the case of that international gag rule, organizations receiving U.S. government funds are not only prevented from providing abortion services or referrals directly, but may not donate money from any source to other organizations that do. Most of these organizations provide many other health services for women from birth control to cancer and HIV treatment. Clearly, preserving the "right to life" doesn't apply to the lives of actual women in this country or the developing world.

So the current perilous state of reproductive liberty is part of why I'm talking about my abortion now. But there's another reason. When I spent time in Central America in the 1980s, I found that the first question women I met often asked me was "Cuantos hijos tiene?" -- "How many children do you have?" They assumed that a woman in her early thirties would have children and this was their (very reasonable) way of reaching out across a cultural divide, of looking for commonality with this gringa who'd landed in their community. I was always a little embarrassed that the answer was "none." I would respond, however, that, although I had no children of my own, I had a compromiso -- a commitment -- to making the world a better place for children everywhere.

I was certainly telling them the truth then -- and I hope my life since hasn't made a liar of me -- but at the time, in some secret part of myself, I also believed that my decision not to have children was a selfish one. There was too much I wanted to do in my own life to voluntarily take on the responsibility for the lives of dependent others. Now, though, as the horrors of climate change reveal themselves daily, I sometimes think that choosing not to bring another resource-devouring, fossil-fuel-burning, carbon-dioxide-emitting American into the world might actually have been the most unselfish thing I've ever done.