SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

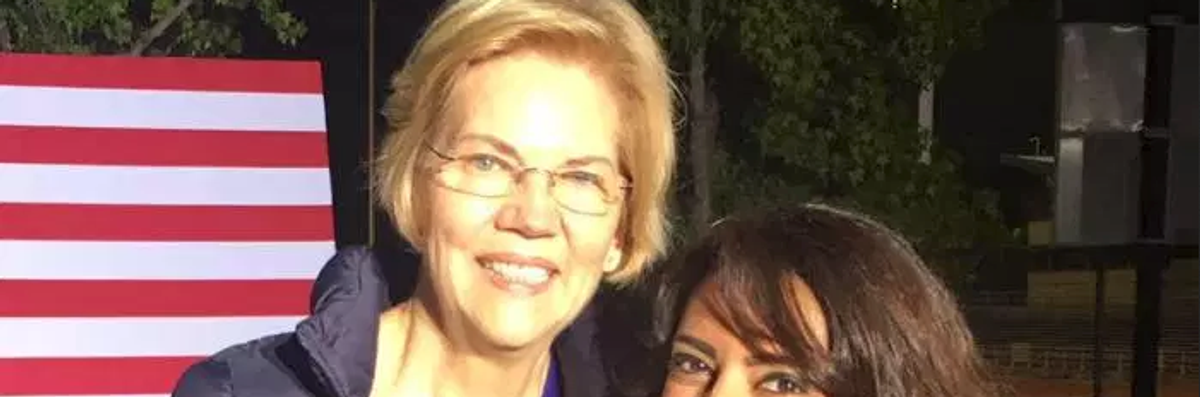

2020 Democratic presidential candidate Sen. Elizabeth Warren pictured with educator Sonya Mehta at rally in Oakland, California last week.

The Internet is a costume party in which everyone comes dressed in an opinion, or rather dozens of them or an endless array, one right after another. An opinion is, traditionally or at least ideally, a conclusion reached after weighing the evidence, but that takes time and so people are dashing about in sloppy, ill-formed opinions or rather snap judgments which are to well-formed opinions what trash bags are to evening gowns. If opinions were like clothes, this would just be awkward, but opinions are also like votes. They shape the discourse and eventually the reality of the world we live in. Journalists used to say that everyone is entitled to their own opinion, but not their own facts, but opinions are supposed to be based on facts and when the facts are wrong or distorted or weaponized, trouble sets in.

There was actually a nice victory over distortion and insinuation a couple of weeks ago. The Washington Post put out a story on May 23 that was titled "While teaching, Elizabeth Warren worked on more than 50 legal matters, charging as much as $675 an hour." (If you look it up now, the title has been changed to not shout about the money any more.) It was kind of a nonstory: one of the nation's leading bankruptcy lawyers, while teaching at one of the nation's most distinguished law schools, did some work on the side, as law professors apparently often do.

If you didn't know anything about legal experts' compensation rates, $675 an hour might seem high, and the whole thing seemed to be trying to suggest that there was something shady about the whole thing. Perhaps women are not supposed to earn a lot of money, though we knew from the sideswipes about Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez's waitress work that we are not supposed to work in low wage jobs either. Perhaps women are always either too much or not enough. For the record, I am wildly enthused about Warren as a presidential candidate, but I was enthused about accuracy a long time before she came along, and this is a story mostly about accuracy and its opposites. The stories I'm relating could be told about any number of other candidates who've been misrepresented in ways that have stuck as smears.

One of the two journalists, Annie Linskey, had penned an earlier Post story whose headline suggested a desperate reaching for controversy: "Elizabeth Warren reshaped our view of the middle class. But some see an angle." The story declared there had been, "a bitter dispute over the integrity of Warren's work that shadowed her for years as she climbed the academic ladder," which turned out to be one angry competitor whose claims about her integrity didn't hold up, according to others in the field. One of the peculiarities of journalism is that "evenhandedness" can degenerate into pretending that everyone is equivalent, that the fossil fuel industry and the scientists have equally valid positions on climate change, that everyone has to have a scandal and all scandals are approximately the same size.

Response to the Washington Post's story about her $675 an hour was a best case scenario. A barrage of legal experts, lawyers, and law school professors (and Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez) hit social media, while readers hit the Washington Post with 2,700 comments; those that I read were all scathing. By the end of the day, Slate had a story headlined "Washington Post Discovers That Elizabeth Warren Was Paid a Reasonable Fee for Providing Legal Services to Unobjectionable Clients" and Esquire and New York Magazine had also mocked the Post's insinuations.

The first round may be malicious, the second is gullible, and then the weaponized information becomes what everyone thinks they know.

Eight days later, things didn't go as well, perhaps because the misinformation didn't start out in a high-profile outlet. Warren spoke at a big outdoor gathering--the crowd was estimated at 6,500--in Oakland, California, and a young woman introduced her. The introduction was full of praise for public education, for Warren's plan to make preschool affordable by taxing billionaires, for her college debt plan, for "full funding of cradle to college funding as a cornerstone of her presidency." The speaker, Sonya Mehta, had taught kindergarten for five years at an Oakland school that became a nonprofit charter school the year she started, at age 24, and then gone on to work for a ballot campaign to increase public school funding in the county, then for an Oakland educational nonprofit focused on teacher sustainabilty called The Teaching Well.

But an education blogger in Pennsylvania called her a "charter school lobbyist," and then education policy figure Diane Ravitch said on her blog that Warren "was introduced by a representative of Great Oakland Public Schools, a billionaire-funded anti-teacher, pro-charter, pro-'reform' operation." By the end of the week, The Progressive had stated, with a link to the education blogger's piece, that "her introduction at an Oakland rally by a former charter school teacher associated with a charter lobbying organization was seen by some as a calculated signal that she is more supportive of charter schools than her progressive rival, Bernie Sanders."

Seen by some as a calculated signal is both vague and incriminating: we never find out who the some are, but the implication of "calculated signal" is that Mehta was chosen to make a political statement and that that statement is pro-charter school. The calculated signal: would it matter unless Warren was the one making it? So is that an assertion Warren was involved in the decision, or is the vague language a way to have it both ways? The carelessness with which they represented this young woman of color--who had not previously been in the public eye--was also disconcerting.

For the record, Warren has been an ardent public school supporter, a critic of for-profit charter schools, and a fierce opponent of education secretary Betsy DeVos. She's promised she would put a public school teacher in DeVos's job; if elected, she'd also put a former public school special education teacher, herself, in the White House.

In the Bay Area so much heat was arising from the charges that I contacted Mehta to try to shed some light on the situation. This is what she told me: she has never been a lobbyist. She has never been a representative or employee of Great Oakland Public Schools. She was a fellow there in 2014-2015, while working full-time as a teacher, which, she told me, meant she went to a three-hour meeting once a month for several months. She volunteered with the organization later and she supports, she says, "aspects of its work on district budget oversight and parent organizing."

She also told me she helped unionize the school she taught at, supported the 2019 Oakland teacher's strike (which was evident in a social media post of hers earlier this year), went to the state capitol with the strikers to advocate for more public school funding, and works for an organization that also supported the strike directly. She's ardent about Elizabeth Warren and public education and public funding for public education, as she made clear in her short speech.

None of these commenters actually know why Mehta was chosen, or who chose her or what the campaign knew about her, so there isn't a basis for a conclusion about what the campaign thinks, insofar as campaigns think, or to assume that Warren was directly involved in the choice. Therefore they and their readers cannot conclude that it reflects on what Warren believes or intends, but some did anyway. "I don't know" is often the most accurate thing you can say, but it is not the kind of opinion you can dress up in for a party--though it is the kind of statement you can publish as journalism.

The falsehoods and insinuations seem to have influenced a lot of people, and I heard from locals that Warren was losing support and supporters over this. Some of that is on people who were careless about their criteria for reaching a conclusion, but I've seen how this works with earlier smears about earlier candidates: the first round may be malicious, the second is gullible, and then the weaponized information becomes what everyone thinks they know, or a vague unease, or a fuzzy suspicion. It dilutes, a smear becoming a stain becoming a taint.

In my own dreams of educational reform, there's a curriculum focused on how to research anything and check everything, how to understand what is and isn't substantiated by the facts, when you do and don't have the evidence to draw a conclusion, and how to live with the uncertainty and mystery that abound in all of us. Such an education would inoculate against the propaganda, lies, distortions, and rumors that circulate so freely now, on the left and in the center as well as on the right. In the meantime, the responsibility for the news rests with consumers as well as producers, or rather when we accept and repeat statements we too become producers of the beliefs that shape this world. It behooves us to do so with care.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

The Internet is a costume party in which everyone comes dressed in an opinion, or rather dozens of them or an endless array, one right after another. An opinion is, traditionally or at least ideally, a conclusion reached after weighing the evidence, but that takes time and so people are dashing about in sloppy, ill-formed opinions or rather snap judgments which are to well-formed opinions what trash bags are to evening gowns. If opinions were like clothes, this would just be awkward, but opinions are also like votes. They shape the discourse and eventually the reality of the world we live in. Journalists used to say that everyone is entitled to their own opinion, but not their own facts, but opinions are supposed to be based on facts and when the facts are wrong or distorted or weaponized, trouble sets in.

There was actually a nice victory over distortion and insinuation a couple of weeks ago. The Washington Post put out a story on May 23 that was titled "While teaching, Elizabeth Warren worked on more than 50 legal matters, charging as much as $675 an hour." (If you look it up now, the title has been changed to not shout about the money any more.) It was kind of a nonstory: one of the nation's leading bankruptcy lawyers, while teaching at one of the nation's most distinguished law schools, did some work on the side, as law professors apparently often do.

If you didn't know anything about legal experts' compensation rates, $675 an hour might seem high, and the whole thing seemed to be trying to suggest that there was something shady about the whole thing. Perhaps women are not supposed to earn a lot of money, though we knew from the sideswipes about Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez's waitress work that we are not supposed to work in low wage jobs either. Perhaps women are always either too much or not enough. For the record, I am wildly enthused about Warren as a presidential candidate, but I was enthused about accuracy a long time before she came along, and this is a story mostly about accuracy and its opposites. The stories I'm relating could be told about any number of other candidates who've been misrepresented in ways that have stuck as smears.

One of the two journalists, Annie Linskey, had penned an earlier Post story whose headline suggested a desperate reaching for controversy: "Elizabeth Warren reshaped our view of the middle class. But some see an angle." The story declared there had been, "a bitter dispute over the integrity of Warren's work that shadowed her for years as she climbed the academic ladder," which turned out to be one angry competitor whose claims about her integrity didn't hold up, according to others in the field. One of the peculiarities of journalism is that "evenhandedness" can degenerate into pretending that everyone is equivalent, that the fossil fuel industry and the scientists have equally valid positions on climate change, that everyone has to have a scandal and all scandals are approximately the same size.

Response to the Washington Post's story about her $675 an hour was a best case scenario. A barrage of legal experts, lawyers, and law school professors (and Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez) hit social media, while readers hit the Washington Post with 2,700 comments; those that I read were all scathing. By the end of the day, Slate had a story headlined "Washington Post Discovers That Elizabeth Warren Was Paid a Reasonable Fee for Providing Legal Services to Unobjectionable Clients" and Esquire and New York Magazine had also mocked the Post's insinuations.

The first round may be malicious, the second is gullible, and then the weaponized information becomes what everyone thinks they know.

Eight days later, things didn't go as well, perhaps because the misinformation didn't start out in a high-profile outlet. Warren spoke at a big outdoor gathering--the crowd was estimated at 6,500--in Oakland, California, and a young woman introduced her. The introduction was full of praise for public education, for Warren's plan to make preschool affordable by taxing billionaires, for her college debt plan, for "full funding of cradle to college funding as a cornerstone of her presidency." The speaker, Sonya Mehta, had taught kindergarten for five years at an Oakland school that became a nonprofit charter school the year she started, at age 24, and then gone on to work for a ballot campaign to increase public school funding in the county, then for an Oakland educational nonprofit focused on teacher sustainabilty called The Teaching Well.

But an education blogger in Pennsylvania called her a "charter school lobbyist," and then education policy figure Diane Ravitch said on her blog that Warren "was introduced by a representative of Great Oakland Public Schools, a billionaire-funded anti-teacher, pro-charter, pro-'reform' operation." By the end of the week, The Progressive had stated, with a link to the education blogger's piece, that "her introduction at an Oakland rally by a former charter school teacher associated with a charter lobbying organization was seen by some as a calculated signal that she is more supportive of charter schools than her progressive rival, Bernie Sanders."

Seen by some as a calculated signal is both vague and incriminating: we never find out who the some are, but the implication of "calculated signal" is that Mehta was chosen to make a political statement and that that statement is pro-charter school. The calculated signal: would it matter unless Warren was the one making it? So is that an assertion Warren was involved in the decision, or is the vague language a way to have it both ways? The carelessness with which they represented this young woman of color--who had not previously been in the public eye--was also disconcerting.

For the record, Warren has been an ardent public school supporter, a critic of for-profit charter schools, and a fierce opponent of education secretary Betsy DeVos. She's promised she would put a public school teacher in DeVos's job; if elected, she'd also put a former public school special education teacher, herself, in the White House.

In the Bay Area so much heat was arising from the charges that I contacted Mehta to try to shed some light on the situation. This is what she told me: she has never been a lobbyist. She has never been a representative or employee of Great Oakland Public Schools. She was a fellow there in 2014-2015, while working full-time as a teacher, which, she told me, meant she went to a three-hour meeting once a month for several months. She volunteered with the organization later and she supports, she says, "aspects of its work on district budget oversight and parent organizing."

She also told me she helped unionize the school she taught at, supported the 2019 Oakland teacher's strike (which was evident in a social media post of hers earlier this year), went to the state capitol with the strikers to advocate for more public school funding, and works for an organization that also supported the strike directly. She's ardent about Elizabeth Warren and public education and public funding for public education, as she made clear in her short speech.

None of these commenters actually know why Mehta was chosen, or who chose her or what the campaign knew about her, so there isn't a basis for a conclusion about what the campaign thinks, insofar as campaigns think, or to assume that Warren was directly involved in the choice. Therefore they and their readers cannot conclude that it reflects on what Warren believes or intends, but some did anyway. "I don't know" is often the most accurate thing you can say, but it is not the kind of opinion you can dress up in for a party--though it is the kind of statement you can publish as journalism.

The falsehoods and insinuations seem to have influenced a lot of people, and I heard from locals that Warren was losing support and supporters over this. Some of that is on people who were careless about their criteria for reaching a conclusion, but I've seen how this works with earlier smears about earlier candidates: the first round may be malicious, the second is gullible, and then the weaponized information becomes what everyone thinks they know, or a vague unease, or a fuzzy suspicion. It dilutes, a smear becoming a stain becoming a taint.

In my own dreams of educational reform, there's a curriculum focused on how to research anything and check everything, how to understand what is and isn't substantiated by the facts, when you do and don't have the evidence to draw a conclusion, and how to live with the uncertainty and mystery that abound in all of us. Such an education would inoculate against the propaganda, lies, distortions, and rumors that circulate so freely now, on the left and in the center as well as on the right. In the meantime, the responsibility for the news rests with consumers as well as producers, or rather when we accept and repeat statements we too become producers of the beliefs that shape this world. It behooves us to do so with care.

The Internet is a costume party in which everyone comes dressed in an opinion, or rather dozens of them or an endless array, one right after another. An opinion is, traditionally or at least ideally, a conclusion reached after weighing the evidence, but that takes time and so people are dashing about in sloppy, ill-formed opinions or rather snap judgments which are to well-formed opinions what trash bags are to evening gowns. If opinions were like clothes, this would just be awkward, but opinions are also like votes. They shape the discourse and eventually the reality of the world we live in. Journalists used to say that everyone is entitled to their own opinion, but not their own facts, but opinions are supposed to be based on facts and when the facts are wrong or distorted or weaponized, trouble sets in.

There was actually a nice victory over distortion and insinuation a couple of weeks ago. The Washington Post put out a story on May 23 that was titled "While teaching, Elizabeth Warren worked on more than 50 legal matters, charging as much as $675 an hour." (If you look it up now, the title has been changed to not shout about the money any more.) It was kind of a nonstory: one of the nation's leading bankruptcy lawyers, while teaching at one of the nation's most distinguished law schools, did some work on the side, as law professors apparently often do.

If you didn't know anything about legal experts' compensation rates, $675 an hour might seem high, and the whole thing seemed to be trying to suggest that there was something shady about the whole thing. Perhaps women are not supposed to earn a lot of money, though we knew from the sideswipes about Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez's waitress work that we are not supposed to work in low wage jobs either. Perhaps women are always either too much or not enough. For the record, I am wildly enthused about Warren as a presidential candidate, but I was enthused about accuracy a long time before she came along, and this is a story mostly about accuracy and its opposites. The stories I'm relating could be told about any number of other candidates who've been misrepresented in ways that have stuck as smears.

One of the two journalists, Annie Linskey, had penned an earlier Post story whose headline suggested a desperate reaching for controversy: "Elizabeth Warren reshaped our view of the middle class. But some see an angle." The story declared there had been, "a bitter dispute over the integrity of Warren's work that shadowed her for years as she climbed the academic ladder," which turned out to be one angry competitor whose claims about her integrity didn't hold up, according to others in the field. One of the peculiarities of journalism is that "evenhandedness" can degenerate into pretending that everyone is equivalent, that the fossil fuel industry and the scientists have equally valid positions on climate change, that everyone has to have a scandal and all scandals are approximately the same size.

Response to the Washington Post's story about her $675 an hour was a best case scenario. A barrage of legal experts, lawyers, and law school professors (and Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez) hit social media, while readers hit the Washington Post with 2,700 comments; those that I read were all scathing. By the end of the day, Slate had a story headlined "Washington Post Discovers That Elizabeth Warren Was Paid a Reasonable Fee for Providing Legal Services to Unobjectionable Clients" and Esquire and New York Magazine had also mocked the Post's insinuations.

The first round may be malicious, the second is gullible, and then the weaponized information becomes what everyone thinks they know.

Eight days later, things didn't go as well, perhaps because the misinformation didn't start out in a high-profile outlet. Warren spoke at a big outdoor gathering--the crowd was estimated at 6,500--in Oakland, California, and a young woman introduced her. The introduction was full of praise for public education, for Warren's plan to make preschool affordable by taxing billionaires, for her college debt plan, for "full funding of cradle to college funding as a cornerstone of her presidency." The speaker, Sonya Mehta, had taught kindergarten for five years at an Oakland school that became a nonprofit charter school the year she started, at age 24, and then gone on to work for a ballot campaign to increase public school funding in the county, then for an Oakland educational nonprofit focused on teacher sustainabilty called The Teaching Well.

But an education blogger in Pennsylvania called her a "charter school lobbyist," and then education policy figure Diane Ravitch said on her blog that Warren "was introduced by a representative of Great Oakland Public Schools, a billionaire-funded anti-teacher, pro-charter, pro-'reform' operation." By the end of the week, The Progressive had stated, with a link to the education blogger's piece, that "her introduction at an Oakland rally by a former charter school teacher associated with a charter lobbying organization was seen by some as a calculated signal that she is more supportive of charter schools than her progressive rival, Bernie Sanders."

Seen by some as a calculated signal is both vague and incriminating: we never find out who the some are, but the implication of "calculated signal" is that Mehta was chosen to make a political statement and that that statement is pro-charter school. The calculated signal: would it matter unless Warren was the one making it? So is that an assertion Warren was involved in the decision, or is the vague language a way to have it both ways? The carelessness with which they represented this young woman of color--who had not previously been in the public eye--was also disconcerting.

For the record, Warren has been an ardent public school supporter, a critic of for-profit charter schools, and a fierce opponent of education secretary Betsy DeVos. She's promised she would put a public school teacher in DeVos's job; if elected, she'd also put a former public school special education teacher, herself, in the White House.

In the Bay Area so much heat was arising from the charges that I contacted Mehta to try to shed some light on the situation. This is what she told me: she has never been a lobbyist. She has never been a representative or employee of Great Oakland Public Schools. She was a fellow there in 2014-2015, while working full-time as a teacher, which, she told me, meant she went to a three-hour meeting once a month for several months. She volunteered with the organization later and she supports, she says, "aspects of its work on district budget oversight and parent organizing."

She also told me she helped unionize the school she taught at, supported the 2019 Oakland teacher's strike (which was evident in a social media post of hers earlier this year), went to the state capitol with the strikers to advocate for more public school funding, and works for an organization that also supported the strike directly. She's ardent about Elizabeth Warren and public education and public funding for public education, as she made clear in her short speech.

None of these commenters actually know why Mehta was chosen, or who chose her or what the campaign knew about her, so there isn't a basis for a conclusion about what the campaign thinks, insofar as campaigns think, or to assume that Warren was directly involved in the choice. Therefore they and their readers cannot conclude that it reflects on what Warren believes or intends, but some did anyway. "I don't know" is often the most accurate thing you can say, but it is not the kind of opinion you can dress up in for a party--though it is the kind of statement you can publish as journalism.

The falsehoods and insinuations seem to have influenced a lot of people, and I heard from locals that Warren was losing support and supporters over this. Some of that is on people who were careless about their criteria for reaching a conclusion, but I've seen how this works with earlier smears about earlier candidates: the first round may be malicious, the second is gullible, and then the weaponized information becomes what everyone thinks they know, or a vague unease, or a fuzzy suspicion. It dilutes, a smear becoming a stain becoming a taint.

In my own dreams of educational reform, there's a curriculum focused on how to research anything and check everything, how to understand what is and isn't substantiated by the facts, when you do and don't have the evidence to draw a conclusion, and how to live with the uncertainty and mystery that abound in all of us. Such an education would inoculate against the propaganda, lies, distortions, and rumors that circulate so freely now, on the left and in the center as well as on the right. In the meantime, the responsibility for the news rests with consumers as well as producers, or rather when we accept and repeat statements we too become producers of the beliefs that shape this world. It behooves us to do so with care.