We all know how thoroughly Bernie Sanders shook up American politics, particularly within the Democratic Party, when he took his challenge to the generally unchallenged, and usually unspoken rule of big money in politics. Even now they're starting to argue about whether he's the party's 2020 frontrunner. And yet political currents at home and abroad suggest a case for him doing something that could shake up the applecart just as thoroughly for a second time - by actually becoming a Democrat for keeps.

It's not as if his record as the longest-serving independent in the history of the U.S. Congress (a status only interrupted during his run for the presidential nomination) hasn't served him well, or anything like that. Clearly it's been a significant contributor to the fact that even people who disagree with him regard him as a straight-shooter. No, so far as his own career goes, Sanders might just as well stay independent. It could well be the case, however, that the enthusiasm his campaign has injected into mainstream politics would be more effectively channeled if he made his plunge into party politics permanent. The question ultimately comes down to one of unity - and clarity of purpose. What would best unify the broad swath of activists and potential activists trying to develop a political force capable of breaking corporate dominance in American politics?

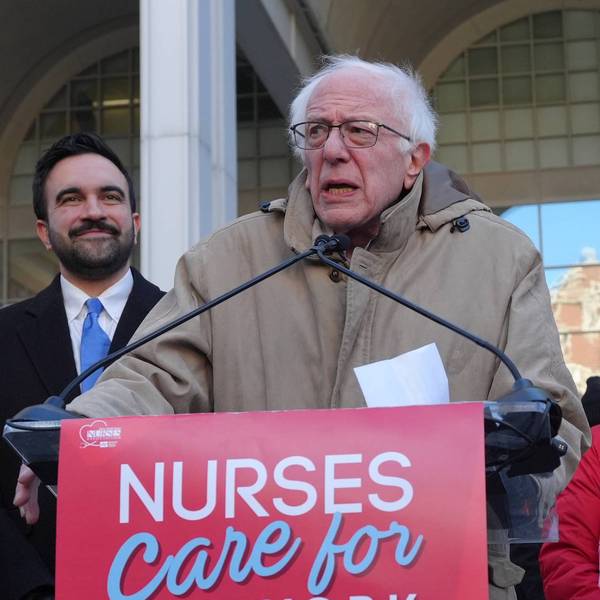

Sometimes things can be clearer from the outside looking in. Canadian author Naomi Klein, for instance, while recognizing the difficulty "of taking over a party that has been colonized by neoliberalism and by the interests of economic elites who do not want to change"--i.e., the Democratic Party--understands the effort as an unavoidable part of a "battle for the soul of, not just the party, but the country." This perspective seems not always as clear back home, though, where only recently Rose Ann DeMoro, executive director of National Nurses United--an organization as closely linked to the Sanders campaign as any--warned a California Democratic Party convention that "If we dismiss progressive values and reinforce the status quo, don't assume the activists in California and around this country are going to stay with the Democratic Party."

And yet, isn't that precisely what those committed to maintaining the status quo of big money hegemony in politics should assume--that the activists are going to stay and fight to end their control of both major parties? Their worst nightmare is not that we will pick up and leave if we don't get what we want, but that we won't leave!

Meanwhile, for those who fear that abandoning capital "I" political Independent status necessarily means compromising small "i" independence in the eyes of the electorate, you won't find a better example of that ethos than in the recent experience of Jeremy Corbyn and the British Labour Party. For all of the grievances that some people who came into electoral politics with the Sanders campaign may have against the Democratic Party, they surely pale in comparison with Corbyn's treatment at the hands of the Labour Party, whose Members of Parliament last year voted no confidence in him by a 172-57 margin, despite his enthusiastic support among the party rank and file. (And his treatment in the establishment media was even worse.)

But still he--and they--persisted, ultimately producing an electoral platform that proposed re-nationalization of the railways, free public higher education, and a range of other policies that proved to resonate far better with the electorate that those of the pro-business New Labour types who frown upon them--and him.

Why did Corbyn's supporters stay and fight in a party where they were so clearly unwelcome? Because if they were serious about changing their country, there was nowhere else to go. Which is much the situation we face in regard to the Democratic Party here, where any smart big money guy has got to hope that the anti-corporate control types will get fed up with feeling unloved and leave the field to those who've been running the show.

Any decision as to Sanders's political status is obviously ultimately his to make, of course. Yet his oft-stated point, "It's not about me, it's us"--so central to his campaign--does suggest that the consideration is a legitimate matter for all of "us." And one can't help but wonder if Bernie Sanders couldn't add a measure of clarity to the current situation.