Is Political Inequality the Worst Kind?

The most pernicious form of inequality—political inequality—is one of the least discussed.

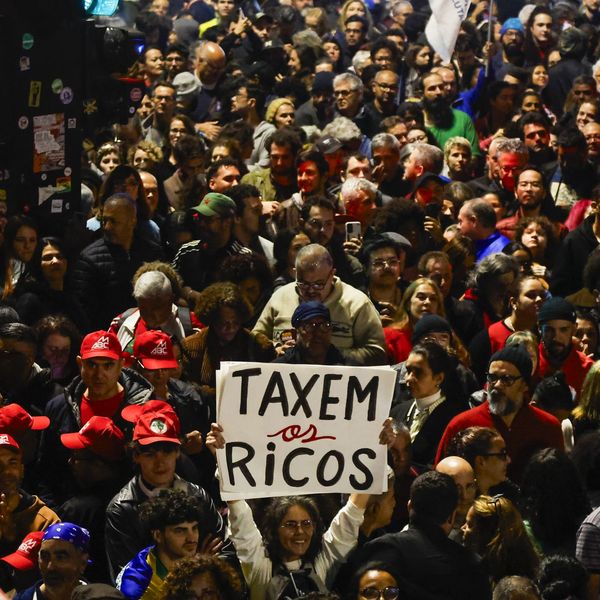

There is enormous focus these days on economic inequality, and for good reason. The gap between the top 1 percent and other Americans is growing, the middle class that built the country and ensured social stability is shrinking, and the likely consequences of those phenomena aren't pretty.

Discussions about equality often run aground due to our different definitions of the term. That's especially true in the United States, where our Constitution guarantees us only equality before the law. Cynics may quote Anatole France for the proposition that "In its majestic equality, the law forbids rich and poor alike to sleep under bridges, beg in the streets and steal loaves of bread," but ours is a system of negative rights--a system that protects individual liberties against encroachments by the state. Efforts to ameliorate material deprivations are thus statutory, not constitutional, and as we have seen, those statutory entitlements are vulnerable to ideological efforts to punish poor people.

Our public discourse around "equality" tends to focus on issues of legal and economic equality and the relationship--or conflict--between the two. We rarely discuss a third kind of equality--democratic equality--despite the fact that it has a major influence on whether the country achieves the others.

Democratic equality simply means the equal right of each citizen to vote, and to participate in the democratic process. It probably won't come as a surprise to find that we aren't doing terribly well on that front, either.

The influence of money in politics has grown exponentially since the Supreme Court's ill-considered decision in Citizens United. Ever since the case of Buckley v. Valeo, the Court has conflated money with speech, and the result has been that those with money are able to "speak" much more loudly and effectively than the rest of us. When democracy becomes "pay to play," there is no equality of participation.

It isn't just money. In my state--which is unfortunately not an outlier-- the legislature has used its power to make it more difficult to vote.

We have one of the strictest Voter ID laws in the nation--in order to cast a ballot, you must not only have a government-issued picture ID, that ID must have an expiration date. (This excludes the IDs issued by state universities, which lack an expiration date.) Middle-class folks assume that it's simple enough to obtain such identification, but for poorer people--particularly older black citizens who were born at home and lack a birth certificate--getting the necessary documentation can be both onerous and costly. (Despite pious rhetoric about deterring "voter fraud," scholars agree that the incidence of fraudulent in-person voting is virtually nil.)

My state legislature has also declined to enact other measures that encourage or facilitate voting by working-class Americans: keeping the polls open past six, establishing convenient voting centers, expanding early voting.

It's bad enough that lawmakers see fit to erect barriers to voting rather than making it easier. But the most serious denial of democratic equality comes through partisan gerrymandering that produces an abundance of "safe" seats and eliminates voter choice.

Increasingly, especially at the state level, our legislators choose their voters--the voters don't choose their representatives. So even when disadvantaged folks make it past the obstacles and manage to cast their ballots, they often find they are given no meaningful choice. A growing number of elections are uncontested.

The result of all this is a particularly pernicious form of inequality--the people who would benefit most from the election of candidates willing to work for legal and/or economic equality--have less access, less influence and less voice.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

There is enormous focus these days on economic inequality, and for good reason. The gap between the top 1 percent and other Americans is growing, the middle class that built the country and ensured social stability is shrinking, and the likely consequences of those phenomena aren't pretty.

Discussions about equality often run aground due to our different definitions of the term. That's especially true in the United States, where our Constitution guarantees us only equality before the law. Cynics may quote Anatole France for the proposition that "In its majestic equality, the law forbids rich and poor alike to sleep under bridges, beg in the streets and steal loaves of bread," but ours is a system of negative rights--a system that protects individual liberties against encroachments by the state. Efforts to ameliorate material deprivations are thus statutory, not constitutional, and as we have seen, those statutory entitlements are vulnerable to ideological efforts to punish poor people.

Our public discourse around "equality" tends to focus on issues of legal and economic equality and the relationship--or conflict--between the two. We rarely discuss a third kind of equality--democratic equality--despite the fact that it has a major influence on whether the country achieves the others.

Democratic equality simply means the equal right of each citizen to vote, and to participate in the democratic process. It probably won't come as a surprise to find that we aren't doing terribly well on that front, either.

The influence of money in politics has grown exponentially since the Supreme Court's ill-considered decision in Citizens United. Ever since the case of Buckley v. Valeo, the Court has conflated money with speech, and the result has been that those with money are able to "speak" much more loudly and effectively than the rest of us. When democracy becomes "pay to play," there is no equality of participation.

It isn't just money. In my state--which is unfortunately not an outlier-- the legislature has used its power to make it more difficult to vote.

We have one of the strictest Voter ID laws in the nation--in order to cast a ballot, you must not only have a government-issued picture ID, that ID must have an expiration date. (This excludes the IDs issued by state universities, which lack an expiration date.) Middle-class folks assume that it's simple enough to obtain such identification, but for poorer people--particularly older black citizens who were born at home and lack a birth certificate--getting the necessary documentation can be both onerous and costly. (Despite pious rhetoric about deterring "voter fraud," scholars agree that the incidence of fraudulent in-person voting is virtually nil.)

My state legislature has also declined to enact other measures that encourage or facilitate voting by working-class Americans: keeping the polls open past six, establishing convenient voting centers, expanding early voting.

It's bad enough that lawmakers see fit to erect barriers to voting rather than making it easier. But the most serious denial of democratic equality comes through partisan gerrymandering that produces an abundance of "safe" seats and eliminates voter choice.

Increasingly, especially at the state level, our legislators choose their voters--the voters don't choose their representatives. So even when disadvantaged folks make it past the obstacles and manage to cast their ballots, they often find they are given no meaningful choice. A growing number of elections are uncontested.

The result of all this is a particularly pernicious form of inequality--the people who would benefit most from the election of candidates willing to work for legal and/or economic equality--have less access, less influence and less voice.

There is enormous focus these days on economic inequality, and for good reason. The gap between the top 1 percent and other Americans is growing, the middle class that built the country and ensured social stability is shrinking, and the likely consequences of those phenomena aren't pretty.

Discussions about equality often run aground due to our different definitions of the term. That's especially true in the United States, where our Constitution guarantees us only equality before the law. Cynics may quote Anatole France for the proposition that "In its majestic equality, the law forbids rich and poor alike to sleep under bridges, beg in the streets and steal loaves of bread," but ours is a system of negative rights--a system that protects individual liberties against encroachments by the state. Efforts to ameliorate material deprivations are thus statutory, not constitutional, and as we have seen, those statutory entitlements are vulnerable to ideological efforts to punish poor people.

Our public discourse around "equality" tends to focus on issues of legal and economic equality and the relationship--or conflict--between the two. We rarely discuss a third kind of equality--democratic equality--despite the fact that it has a major influence on whether the country achieves the others.

Democratic equality simply means the equal right of each citizen to vote, and to participate in the democratic process. It probably won't come as a surprise to find that we aren't doing terribly well on that front, either.

The influence of money in politics has grown exponentially since the Supreme Court's ill-considered decision in Citizens United. Ever since the case of Buckley v. Valeo, the Court has conflated money with speech, and the result has been that those with money are able to "speak" much more loudly and effectively than the rest of us. When democracy becomes "pay to play," there is no equality of participation.

It isn't just money. In my state--which is unfortunately not an outlier-- the legislature has used its power to make it more difficult to vote.

We have one of the strictest Voter ID laws in the nation--in order to cast a ballot, you must not only have a government-issued picture ID, that ID must have an expiration date. (This excludes the IDs issued by state universities, which lack an expiration date.) Middle-class folks assume that it's simple enough to obtain such identification, but for poorer people--particularly older black citizens who were born at home and lack a birth certificate--getting the necessary documentation can be both onerous and costly. (Despite pious rhetoric about deterring "voter fraud," scholars agree that the incidence of fraudulent in-person voting is virtually nil.)

My state legislature has also declined to enact other measures that encourage or facilitate voting by working-class Americans: keeping the polls open past six, establishing convenient voting centers, expanding early voting.

It's bad enough that lawmakers see fit to erect barriers to voting rather than making it easier. But the most serious denial of democratic equality comes through partisan gerrymandering that produces an abundance of "safe" seats and eliminates voter choice.

Increasingly, especially at the state level, our legislators choose their voters--the voters don't choose their representatives. So even when disadvantaged folks make it past the obstacles and manage to cast their ballots, they often find they are given no meaningful choice. A growing number of elections are uncontested.

The result of all this is a particularly pernicious form of inequality--the people who would benefit most from the election of candidates willing to work for legal and/or economic equality--have less access, less influence and less voice.