The White House is cloaked in secrecy and Congress doesn't like it. From drone operations to NSA surveillance to under-the-table negotiations of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which many are calling a global corporate coup, representatives are urging the Obama administration to declassify information they feel should be public knowledge. They've written letters, spoken out, and attempted to cut funding for these programs.

But in the midst of all this secrecy and frustration they've either forgotten or ignored their most powerful tool: the Speech or Debate Clause of the Constitution. Both houses of Congress "shall in all Cases, except Treason, Felony, and Breach of the Peace, be privileged from Arrest during their attendance at the Session of their Respective Houses, and in going to and from the same," reads Article 1, Section 6. "And for any Speech or Debate in either House, they shall not be questioned in any other Place."

The Clause protects Congress' autonomy from the Executive. It ensures that representatives can express themselves without having to fear prosecution based on their political beliefs, "in order to enable to encourage a representative of the publick," as James Wilson elaborated in 1791, from "the resentment of every one, however powerful, to whom the exercise of that liberty may occasion offence."

The law is meant to empower the legislative branch lest the president should overstretch his/her limits of control, which seems to be the hallmark of the Obama administration. It's time, then, for our favorite politicians to use it.

The Speech or Debate Clause is not an obscure law. It was enshrined in several court cases, most notably the 1972 Supreme Court case of Gravel v. United States, in which Mike Gravel, the former Senator to Alaska, was prosecuted for entering the then classified Pentagon Papers into the public record as well as arranging for its publication in the Beacon Press. The Senator, who had received a copy of the document from an editor at the Washington Post, felt that the atrocities committed by the U.S. in Vietnam were not something that should be hidden from the American public. In a 5 to 4 ruling, the Supreme Court reaffirmed Gravel's right to free speech without impunity and extended that right to his congressional aides, as long as that speech was relevant to his position as a member of Congress.

So where are the Gravels of today? Some point to Senators Ron Wyden (D-Oregon) and Mark Udall (D-Colorado), who've been longtime critics of the NSA's surveillance programs as well as the CIA's drone operations. Wyden and Udall have access to classified information, like Gravel did in 1971, that they feel should be disclosed to the public. But they've portrayed themselves as stifled crusaders, well-intentioned politicians who only wish that they could reveal more than just the "tip of the iceberg."

Well legally they can, in accordance with the Speech or Debate Clause. In fact, Wyden had thought a lot about leaking information on the NSA surveillance programs before Snowden he said in a recent interview with Rolling Stone, deciding finally against doing so because, being in "a watchdog role, you try to work within the rules."

The same can be said about U.S. drone operations abroad. Although it is true that even members of the Senate intelligence committee are not being given all the information they need for proper oversight, they're still kept loosely in the loop and "receive notification with key details of each strike," Dianne Feinstein wrote in February, "shortly after [the drone strikes] occur."

Yet Wyden, Udall, and Senator Angus King (I-Maine), all of whom have been critical of the president acting as judge, jury and executioner and are members of the intelligence committee, have refused to expose details on this new kind of warfare, which has pulled the U.S. into three new battlefields - Yemen, Pakistan and Somalia - and which, by some estimates, has killed more than 3,000 people.

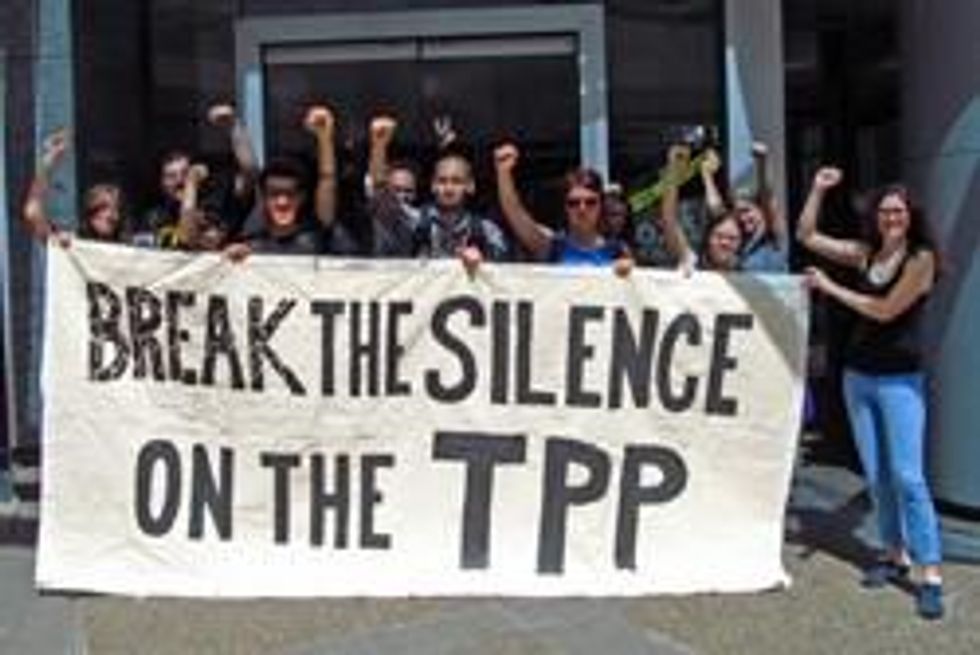

Finally, there's the Trans-Pacific Partnership, or TPP, which stands as the most important trade deal of the last thirty years and which is also being concealed from the people it would affect most: the poor. In short, it's an agreement that will fine and punish countries and communities that don't open up their floodgates to corporate development and ownership, whether it be natural resources, labor, or the Internet. It'll be a win-win for corporations: either countries get out of the way of corporate projects, or face suits when they try to impose rules and regulations, usually resulting in their having to compensate companies for expected lost profits.

The negotiations are conducted in secret with the help of 600 corporate advisors and Congress has had limited access to the texts coming out of the negotiations. There are members of Congress who've been given permission to look at the documents coming out of these secret meetings, but those documents have been - you guessed correctly - labeled as classified.

So again, for those Congress members who've been given access to those documents, their voices are muffled. Rep. Alan Grayson (D-Florida), who saw an edited version of the TPP text, said that if Americans knew what was going on behind these closed doors many would be horrified.

"Having seen what I've seen," he told the Huffington Post in June, "I would characterize this as a gross abrogation of American sovereignty...I would further characterize it as a punch in the face to the middle class of America. I think that's fair to say from what I've seen so far. But I'm not allowed to tell you why."

The image of a helpless Congress is, in many ways, an illusion. It's more accurate to say that representatives today are more reluctant to challenge the executive branch, whose secrecy surrounding the NSA, drones, and the TPP is intimately connected to corporate interests, whether they be to the defense, intelligence, or financial industries.

The tools available to Congress, like the Speech or Debate Clause, haven't changed. But the atmosphere has. With a record number of whistleblowers being prosecuted, along with the relentlessly tightening grip of corporate donors on their politicians, it is becoming more and more difficult to do what Gravel did in 1971 without the fear of consequences. Still, Gravel says, it's no excuse to remain silent.

"The fact is that people like Wyden and Udall," Gravel told me over the phone in July, "who I think are extremely fine Senators, don't have the guts to put their political views aside...When you're a part of the Senate, you're a part of the club. If you do things that don't sit well with the majority, which I've experienced, you receive a great deal of peer pressure. It's a question of putting the principled issue over any selfish, personal issue."