Recognizing the Importance of Goldwater, or Learning to Analyze and Practice Progressive Politics in their Historical Dimension

If you get a chance, you should take a look at the debate between Glen Ford and Michael Eric Dyson that aired as part of the September 7th edition of Amy Goodman's Democracy Now (video below). The extended interchange is valuable for many reasons.

The most immediately evident of these is that it "breaks the silence", as Amy likes to say, on the enormous disdain that many liberals and progressives feel for Obama and his policies.

If you get a chance, you should take a look at the debate between Glen Ford and Michael Eric Dyson that aired as part of the September 7th edition of Amy Goodman's Democracy Now (video below). The extended interchange is valuable for many reasons.

The most immediately evident of these is that it "breaks the silence", as Amy likes to say, on the enormous disdain that many liberals and progressives feel for Obama and his policies.

Faced with the President's glaring record of servitude to the most reactionary forces of our culture--a record he does not even make the slightest effort to dispute--Dyson (think of the verbal torrents of Cornell West but with a dramatically reduced quotient of cognitive and lexical precision) does what so many liberals who like to think of themselves as oh-so-savvy customarily do: he mocks Ford for his lack of practicality and his supposed preference for pristine ideals over the messy work of achieving incremental progress in the "real world" of politics.

As De Tocqueville noticed early on, the ideology of pragmatism (and let's not kid ourselves, as so many in the USA do today, that it is any less an ideology than Communism or Conservatism) has a powerful grip on the American psyche.

The attraction is quite understandable. For the considerable (non-slave and non--indigenous) portion of the early US population that was fleeing from the hierarchical social orders of the Old World, the idea that a person's value would be calibrated not in the light of their class pertinence or their ability to regurgitate a priori bodies of theory, but rather in terms of their ability to produce palpable life improvements in real time, pragmatism was truly intoxicating.

But our enthusiasm for pragmatism comes at a price, a cost we seldom address here in the United States, but that is more than evident to our friends around the world. What they see quite clearly--and what we are largely blind to--is the radically presentist nature of our society's dominant way of framing problems.

In putting so much value on what can be accomplished here and now through whatever means possible, we sadly neglect what theorists call the diachronic, or longitudinal, elements of cultural change, that is, the techniques that have proven effective at engendering large (and arguably much more important and durable) transformations in the social fabric over an extended period of time.

American salesmen, having long understood this particular weakness of our cultural training, have built a many of their approaches to their potential clients around it.

When I go into a car dealership, the first and most essential goal of the sales associate is to convince me that there are special deals on cars today that are better than anything I could expect in the future. He wants to convince me, in effect, that there really is no tomorrow when it comes to my getting the best deal.

Which brings us back to Michael Eric Dyson.

In the debate with Ford, he repeatedly tries to kettle his interlocutor into adopting a rigidly presentist understanding of progressive politics. He constantly states, in one verbally overblown way or another, that all that really matters is this particular political playing field, this particular election, and from there, the particular question of whether he will ultimately say "yes" or "no" to Obama.

I must say I was a bit surprised at the docility with which Ford, who possesses a razor sharp intellect and does not suffer fools gladly, put up with the Toyotathon treatment from Dyson.

Had he been a bit more at the top of his game that day, he might have challenged the Dyson's reductionist approach with something like this.

"Dr. Dyson, you are imploring me and many others with my outlook to vote for Obama in the name of pragmatism. Well, the first and most essential task that those supporting a candidate in the name of pragmatism have is demonstrating the palpable results achieved by that person.

You have clearly failed to generate any such bill of particulars. Rather, you have talked in vague terms about how he would, or could, be better over the next four years than the Republican he will be facing in November. The best you could come up with in terms of a real achievement, was a corporate-designed Health Care Reform that will not even go into effect until 2014.

But let's leave all that aside for a moment and address an arguably more important element of you argument, such as it is.

That would be your hammering insistence that if we want to create a better society, what really needs to be front and center is today's specific game of electoral politics.

I am glad that you think this is so important.

But if you had spent a little more time studying the recent history of social and political transformations in the world, you'd probably have a different view.

I could speak to you about how it was that in Uruguay, in 2004, the country's progressives finally broke the duopoly the elites first imposed upon the population in the 19th century.

Or I could talk about what is going on today in Quebec and Catalonia, and how the transformations there, like those in Uruguay, have little, if anything, to do with slavishly accepting, as you do, the accepted set of available electoral options put forth by the society's power elites.

But perhaps it would be better if we simply looked at how the Republicans, the people you love to vilify, and love to use as a cover for your beloved candidate's mendacious and frequently murderous record, achieved their structural hegemony (in the sense of completely controlling the tone and parameters of our political discourse) within American life at the end of the last century.

As you know, today's Republican party is firmly controlled by its most radically bellicose and anti-social elements. Fifty years ago, however, this was not the case.

In the early 1960s, the Republicans found themselves in a situation quite similar to the one the Democrats find themselves in today; they were completely trapped within the paradigms of reality developed and sold to the American people by the opposing party in the years since the Great Depression

The New Deal, with its implied faith in the ability of government to better the lives of ordinary citizens, was king. Many Republicans grumbled privately about this. Few, however, dared to challenge the core suppositions of the New Deal consensus openly. Indeed, for all his popularity during his two terms in office, Eisenhower never laid a glove on the edifice of state built by Roosevelt and Truman in the thirties and forties.

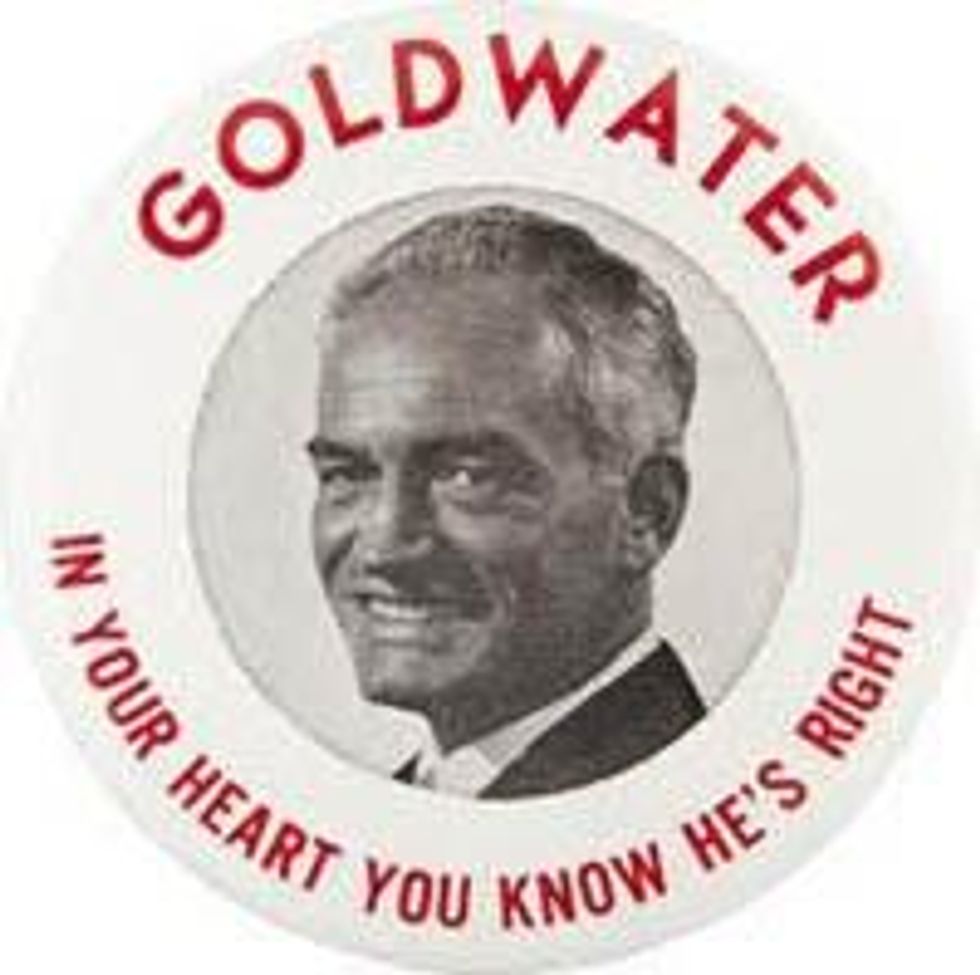

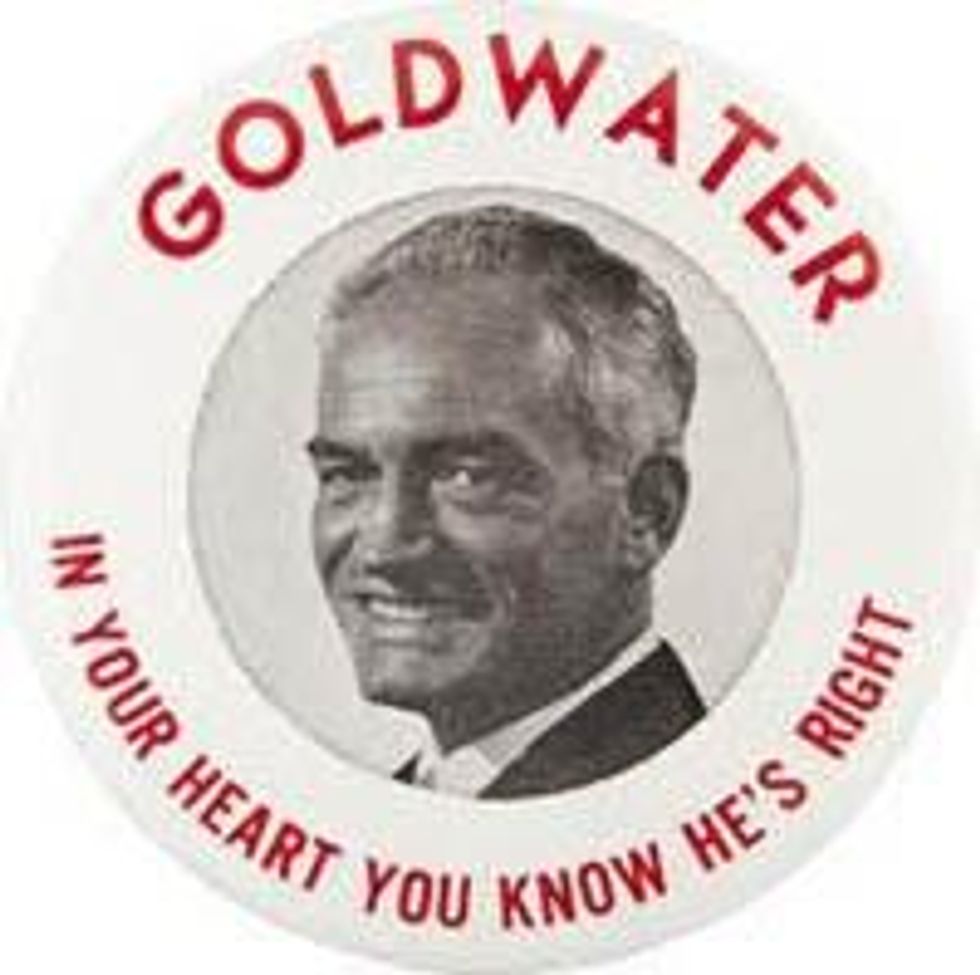

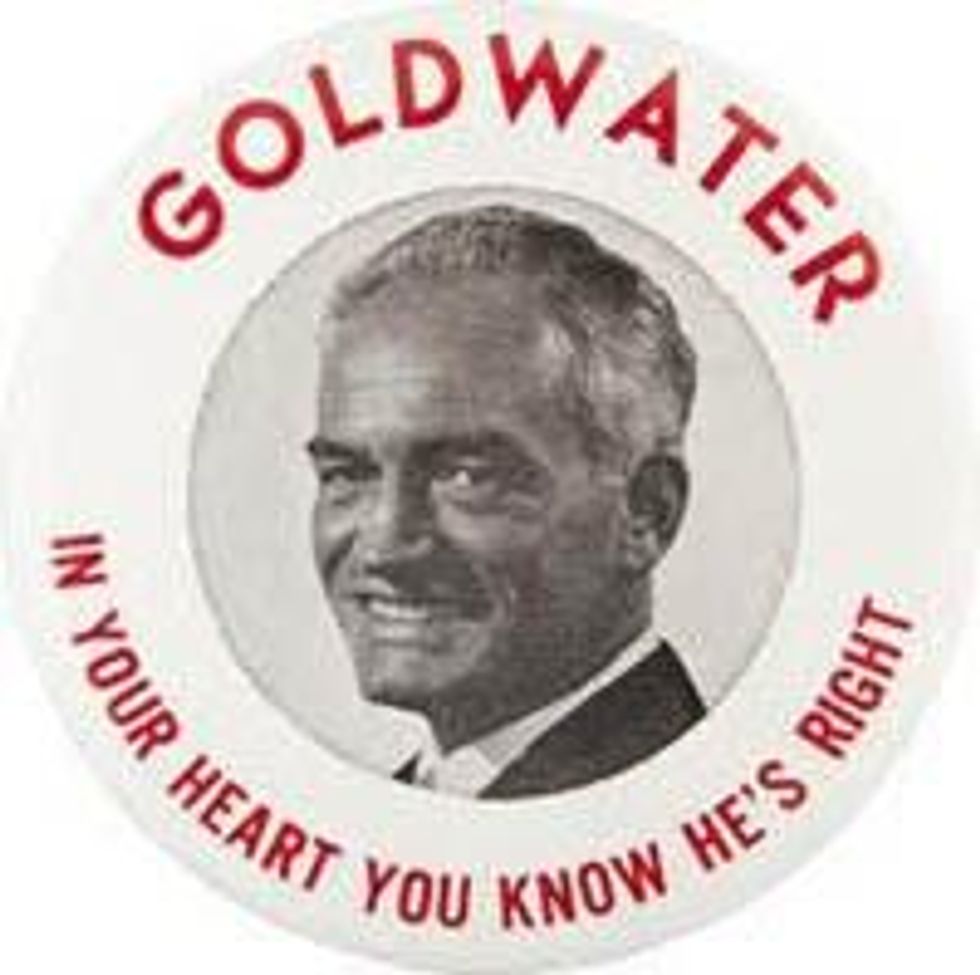

Then along came a man named Barry Goldwater. Goldwater detested the New Deal and the idea that the best course in US foreign policy was to grudgingly accept the prominent role of the Soviet Union in world affairs. And he sensed that there were--lurking beneath the apparent tranquility of our society's New Deal consensus--a whole lot of other people who shared his points of view.

He understood, moreover, that unless someone from his party openly challenged the underlying premises of the New Deal, the Republicans would forever be trapped within its repertoire of political possibilities, and in a decidedly secondary role at that.

And so what did he do?

He ran a campaign for president in which he spoke openly and with conviction about his beliefs.

He, of course, lost and was ridiculed by many of the day's more prominent pundits throughout the process.

But in losing, he carved out a social space for the articulation of his brand of conservative thought. And he let the many people who had come to believe over the previous 25 years that it was fruitless to challenge the assumptions of the New Deal know that they could, in fact, do so in loud voices and live to tell the story.

A mere 16 years later (I realize that for presentists like you that seems like a lot of time, but it really isn't) , Ronald Reagan won the White House on a platform based largely on the "whacky" and "extreme" ideas first articulated on the big stage by Goldwater and his small, enthusiastic, and guilt-free band of supporters in 1964.

Had Goldwater seen the election in the way Dyson want us to see the coming one, which is to say in purely presentist terms, he would have probably acted quite differently. He probably would have tailored his message to attract what the media today loves to call "those all-important centrist voters".

In so doing, he would have no doubt garnered more votes. But he also would have lost the opportunity to begin the process of resetting the dominant paradigms of American political life.

As we enter the fourth decade of the Conservative's effective control of our country's political and social discourses, and we watch one supposedly progressive political actor after another dissolve into mush before the suicidal "conventional wisdom" of our time (forged by the heedless sons and daughters of the Goldwater and Reagan revolutions), isn't it about time that we stop listening to the allegedly "pragmatic" bloviators of the Dyson school and begin to ask what it will take, and more specifically, what sacrifices must we embrace today (including "strategic" election losses), so that tomorrow for our children and grandchildren might inhabit a society that is firmly rooted in concepts of human dignity and progressive values?

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

If you get a chance, you should take a look at the debate between Glen Ford and Michael Eric Dyson that aired as part of the September 7th edition of Amy Goodman's Democracy Now (video below). The extended interchange is valuable for many reasons.

The most immediately evident of these is that it "breaks the silence", as Amy likes to say, on the enormous disdain that many liberals and progressives feel for Obama and his policies.

Faced with the President's glaring record of servitude to the most reactionary forces of our culture--a record he does not even make the slightest effort to dispute--Dyson (think of the verbal torrents of Cornell West but with a dramatically reduced quotient of cognitive and lexical precision) does what so many liberals who like to think of themselves as oh-so-savvy customarily do: he mocks Ford for his lack of practicality and his supposed preference for pristine ideals over the messy work of achieving incremental progress in the "real world" of politics.

As De Tocqueville noticed early on, the ideology of pragmatism (and let's not kid ourselves, as so many in the USA do today, that it is any less an ideology than Communism or Conservatism) has a powerful grip on the American psyche.

The attraction is quite understandable. For the considerable (non-slave and non--indigenous) portion of the early US population that was fleeing from the hierarchical social orders of the Old World, the idea that a person's value would be calibrated not in the light of their class pertinence or their ability to regurgitate a priori bodies of theory, but rather in terms of their ability to produce palpable life improvements in real time, pragmatism was truly intoxicating.

But our enthusiasm for pragmatism comes at a price, a cost we seldom address here in the United States, but that is more than evident to our friends around the world. What they see quite clearly--and what we are largely blind to--is the radically presentist nature of our society's dominant way of framing problems.

In putting so much value on what can be accomplished here and now through whatever means possible, we sadly neglect what theorists call the diachronic, or longitudinal, elements of cultural change, that is, the techniques that have proven effective at engendering large (and arguably much more important and durable) transformations in the social fabric over an extended period of time.

American salesmen, having long understood this particular weakness of our cultural training, have built a many of their approaches to their potential clients around it.

When I go into a car dealership, the first and most essential goal of the sales associate is to convince me that there are special deals on cars today that are better than anything I could expect in the future. He wants to convince me, in effect, that there really is no tomorrow when it comes to my getting the best deal.

Which brings us back to Michael Eric Dyson.

In the debate with Ford, he repeatedly tries to kettle his interlocutor into adopting a rigidly presentist understanding of progressive politics. He constantly states, in one verbally overblown way or another, that all that really matters is this particular political playing field, this particular election, and from there, the particular question of whether he will ultimately say "yes" or "no" to Obama.

I must say I was a bit surprised at the docility with which Ford, who possesses a razor sharp intellect and does not suffer fools gladly, put up with the Toyotathon treatment from Dyson.

Had he been a bit more at the top of his game that day, he might have challenged the Dyson's reductionist approach with something like this.

"Dr. Dyson, you are imploring me and many others with my outlook to vote for Obama in the name of pragmatism. Well, the first and most essential task that those supporting a candidate in the name of pragmatism have is demonstrating the palpable results achieved by that person.

You have clearly failed to generate any such bill of particulars. Rather, you have talked in vague terms about how he would, or could, be better over the next four years than the Republican he will be facing in November. The best you could come up with in terms of a real achievement, was a corporate-designed Health Care Reform that will not even go into effect until 2014.

But let's leave all that aside for a moment and address an arguably more important element of you argument, such as it is.

That would be your hammering insistence that if we want to create a better society, what really needs to be front and center is today's specific game of electoral politics.

I am glad that you think this is so important.

But if you had spent a little more time studying the recent history of social and political transformations in the world, you'd probably have a different view.

I could speak to you about how it was that in Uruguay, in 2004, the country's progressives finally broke the duopoly the elites first imposed upon the population in the 19th century.

Or I could talk about what is going on today in Quebec and Catalonia, and how the transformations there, like those in Uruguay, have little, if anything, to do with slavishly accepting, as you do, the accepted set of available electoral options put forth by the society's power elites.

But perhaps it would be better if we simply looked at how the Republicans, the people you love to vilify, and love to use as a cover for your beloved candidate's mendacious and frequently murderous record, achieved their structural hegemony (in the sense of completely controlling the tone and parameters of our political discourse) within American life at the end of the last century.

As you know, today's Republican party is firmly controlled by its most radically bellicose and anti-social elements. Fifty years ago, however, this was not the case.

In the early 1960s, the Republicans found themselves in a situation quite similar to the one the Democrats find themselves in today; they were completely trapped within the paradigms of reality developed and sold to the American people by the opposing party in the years since the Great Depression

The New Deal, with its implied faith in the ability of government to better the lives of ordinary citizens, was king. Many Republicans grumbled privately about this. Few, however, dared to challenge the core suppositions of the New Deal consensus openly. Indeed, for all his popularity during his two terms in office, Eisenhower never laid a glove on the edifice of state built by Roosevelt and Truman in the thirties and forties.

Then along came a man named Barry Goldwater. Goldwater detested the New Deal and the idea that the best course in US foreign policy was to grudgingly accept the prominent role of the Soviet Union in world affairs. And he sensed that there were--lurking beneath the apparent tranquility of our society's New Deal consensus--a whole lot of other people who shared his points of view.

He understood, moreover, that unless someone from his party openly challenged the underlying premises of the New Deal, the Republicans would forever be trapped within its repertoire of political possibilities, and in a decidedly secondary role at that.

And so what did he do?

He ran a campaign for president in which he spoke openly and with conviction about his beliefs.

He, of course, lost and was ridiculed by many of the day's more prominent pundits throughout the process.

But in losing, he carved out a social space for the articulation of his brand of conservative thought. And he let the many people who had come to believe over the previous 25 years that it was fruitless to challenge the assumptions of the New Deal know that they could, in fact, do so in loud voices and live to tell the story.

A mere 16 years later (I realize that for presentists like you that seems like a lot of time, but it really isn't) , Ronald Reagan won the White House on a platform based largely on the "whacky" and "extreme" ideas first articulated on the big stage by Goldwater and his small, enthusiastic, and guilt-free band of supporters in 1964.

Had Goldwater seen the election in the way Dyson want us to see the coming one, which is to say in purely presentist terms, he would have probably acted quite differently. He probably would have tailored his message to attract what the media today loves to call "those all-important centrist voters".

In so doing, he would have no doubt garnered more votes. But he also would have lost the opportunity to begin the process of resetting the dominant paradigms of American political life.

As we enter the fourth decade of the Conservative's effective control of our country's political and social discourses, and we watch one supposedly progressive political actor after another dissolve into mush before the suicidal "conventional wisdom" of our time (forged by the heedless sons and daughters of the Goldwater and Reagan revolutions), isn't it about time that we stop listening to the allegedly "pragmatic" bloviators of the Dyson school and begin to ask what it will take, and more specifically, what sacrifices must we embrace today (including "strategic" election losses), so that tomorrow for our children and grandchildren might inhabit a society that is firmly rooted in concepts of human dignity and progressive values?

If you get a chance, you should take a look at the debate between Glen Ford and Michael Eric Dyson that aired as part of the September 7th edition of Amy Goodman's Democracy Now (video below). The extended interchange is valuable for many reasons.

The most immediately evident of these is that it "breaks the silence", as Amy likes to say, on the enormous disdain that many liberals and progressives feel for Obama and his policies.

Faced with the President's glaring record of servitude to the most reactionary forces of our culture--a record he does not even make the slightest effort to dispute--Dyson (think of the verbal torrents of Cornell West but with a dramatically reduced quotient of cognitive and lexical precision) does what so many liberals who like to think of themselves as oh-so-savvy customarily do: he mocks Ford for his lack of practicality and his supposed preference for pristine ideals over the messy work of achieving incremental progress in the "real world" of politics.

As De Tocqueville noticed early on, the ideology of pragmatism (and let's not kid ourselves, as so many in the USA do today, that it is any less an ideology than Communism or Conservatism) has a powerful grip on the American psyche.

The attraction is quite understandable. For the considerable (non-slave and non--indigenous) portion of the early US population that was fleeing from the hierarchical social orders of the Old World, the idea that a person's value would be calibrated not in the light of their class pertinence or their ability to regurgitate a priori bodies of theory, but rather in terms of their ability to produce palpable life improvements in real time, pragmatism was truly intoxicating.

But our enthusiasm for pragmatism comes at a price, a cost we seldom address here in the United States, but that is more than evident to our friends around the world. What they see quite clearly--and what we are largely blind to--is the radically presentist nature of our society's dominant way of framing problems.

In putting so much value on what can be accomplished here and now through whatever means possible, we sadly neglect what theorists call the diachronic, or longitudinal, elements of cultural change, that is, the techniques that have proven effective at engendering large (and arguably much more important and durable) transformations in the social fabric over an extended period of time.

American salesmen, having long understood this particular weakness of our cultural training, have built a many of their approaches to their potential clients around it.

When I go into a car dealership, the first and most essential goal of the sales associate is to convince me that there are special deals on cars today that are better than anything I could expect in the future. He wants to convince me, in effect, that there really is no tomorrow when it comes to my getting the best deal.

Which brings us back to Michael Eric Dyson.

In the debate with Ford, he repeatedly tries to kettle his interlocutor into adopting a rigidly presentist understanding of progressive politics. He constantly states, in one verbally overblown way or another, that all that really matters is this particular political playing field, this particular election, and from there, the particular question of whether he will ultimately say "yes" or "no" to Obama.

I must say I was a bit surprised at the docility with which Ford, who possesses a razor sharp intellect and does not suffer fools gladly, put up with the Toyotathon treatment from Dyson.

Had he been a bit more at the top of his game that day, he might have challenged the Dyson's reductionist approach with something like this.

"Dr. Dyson, you are imploring me and many others with my outlook to vote for Obama in the name of pragmatism. Well, the first and most essential task that those supporting a candidate in the name of pragmatism have is demonstrating the palpable results achieved by that person.

You have clearly failed to generate any such bill of particulars. Rather, you have talked in vague terms about how he would, or could, be better over the next four years than the Republican he will be facing in November. The best you could come up with in terms of a real achievement, was a corporate-designed Health Care Reform that will not even go into effect until 2014.

But let's leave all that aside for a moment and address an arguably more important element of you argument, such as it is.

That would be your hammering insistence that if we want to create a better society, what really needs to be front and center is today's specific game of electoral politics.

I am glad that you think this is so important.

But if you had spent a little more time studying the recent history of social and political transformations in the world, you'd probably have a different view.

I could speak to you about how it was that in Uruguay, in 2004, the country's progressives finally broke the duopoly the elites first imposed upon the population in the 19th century.

Or I could talk about what is going on today in Quebec and Catalonia, and how the transformations there, like those in Uruguay, have little, if anything, to do with slavishly accepting, as you do, the accepted set of available electoral options put forth by the society's power elites.

But perhaps it would be better if we simply looked at how the Republicans, the people you love to vilify, and love to use as a cover for your beloved candidate's mendacious and frequently murderous record, achieved their structural hegemony (in the sense of completely controlling the tone and parameters of our political discourse) within American life at the end of the last century.

As you know, today's Republican party is firmly controlled by its most radically bellicose and anti-social elements. Fifty years ago, however, this was not the case.

In the early 1960s, the Republicans found themselves in a situation quite similar to the one the Democrats find themselves in today; they were completely trapped within the paradigms of reality developed and sold to the American people by the opposing party in the years since the Great Depression

The New Deal, with its implied faith in the ability of government to better the lives of ordinary citizens, was king. Many Republicans grumbled privately about this. Few, however, dared to challenge the core suppositions of the New Deal consensus openly. Indeed, for all his popularity during his two terms in office, Eisenhower never laid a glove on the edifice of state built by Roosevelt and Truman in the thirties and forties.

Then along came a man named Barry Goldwater. Goldwater detested the New Deal and the idea that the best course in US foreign policy was to grudgingly accept the prominent role of the Soviet Union in world affairs. And he sensed that there were--lurking beneath the apparent tranquility of our society's New Deal consensus--a whole lot of other people who shared his points of view.

He understood, moreover, that unless someone from his party openly challenged the underlying premises of the New Deal, the Republicans would forever be trapped within its repertoire of political possibilities, and in a decidedly secondary role at that.

And so what did he do?

He ran a campaign for president in which he spoke openly and with conviction about his beliefs.

He, of course, lost and was ridiculed by many of the day's more prominent pundits throughout the process.

But in losing, he carved out a social space for the articulation of his brand of conservative thought. And he let the many people who had come to believe over the previous 25 years that it was fruitless to challenge the assumptions of the New Deal know that they could, in fact, do so in loud voices and live to tell the story.

A mere 16 years later (I realize that for presentists like you that seems like a lot of time, but it really isn't) , Ronald Reagan won the White House on a platform based largely on the "whacky" and "extreme" ideas first articulated on the big stage by Goldwater and his small, enthusiastic, and guilt-free band of supporters in 1964.

Had Goldwater seen the election in the way Dyson want us to see the coming one, which is to say in purely presentist terms, he would have probably acted quite differently. He probably would have tailored his message to attract what the media today loves to call "those all-important centrist voters".

In so doing, he would have no doubt garnered more votes. But he also would have lost the opportunity to begin the process of resetting the dominant paradigms of American political life.

As we enter the fourth decade of the Conservative's effective control of our country's political and social discourses, and we watch one supposedly progressive political actor after another dissolve into mush before the suicidal "conventional wisdom" of our time (forged by the heedless sons and daughters of the Goldwater and Reagan revolutions), isn't it about time that we stop listening to the allegedly "pragmatic" bloviators of the Dyson school and begin to ask what it will take, and more specifically, what sacrifices must we embrace today (including "strategic" election losses), so that tomorrow for our children and grandchildren might inhabit a society that is firmly rooted in concepts of human dignity and progressive values?