GOP 'Doubling Down on a Failed Agenda' With New Reconciliation Framework, Says Key Dem

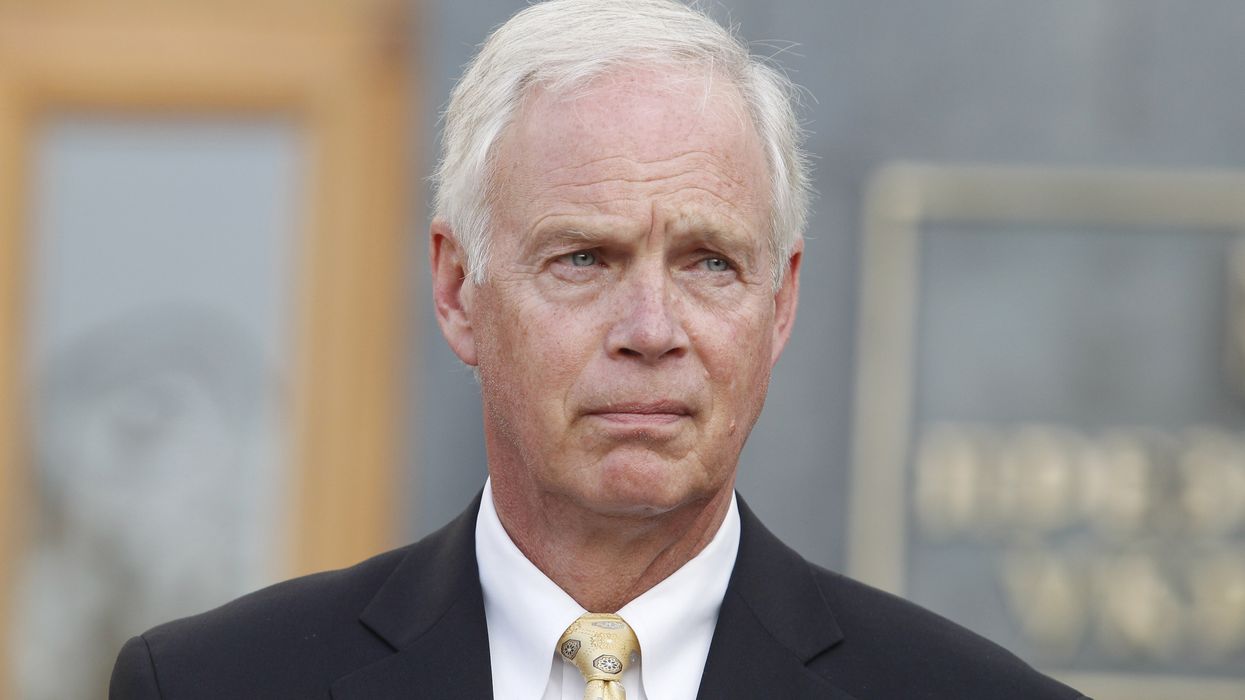

"Americans will pay a steep price if Republicans move forward with this disastrous agenda," said Sen. Ron Wyden.

The House Republican Study Committee on Tuesday released a blueprint for a new budget reconciliation package with the purported goal of making "life more affordable for working families."

However, according to an analysis by Washington Post economic policy reporter Jacob Bogage, two of the three most expensive items in the GOP budget blueprint would be the elimination of the federal estate tax, which would provide a massive windfall to the richest US households, and indexing capital gains to inflation, which even the conservative American Enterprise Institute contends "would further distort taxpayer decisions and increase the ability to shelter income from taxation."

Other items in the GOP blueprint include refilling the Strategic Petroleum Reserve with oil seized from Venezuela, blocking federal funds for abortion providers, and a new "excise tax on colleges that allow trans women in sports."

Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.), ranking member of the Senate Finance Committee, wasted no time ripping the proposal from the largest right-wing House caucus to pieces.

"After passing the largest health care cut in American history, Republicans are doubling down on a failed agenda that benefits billionaires and giant corporations while ripping away food, healthcare and other basic necessities,” Wyden said. “This legislation will eliminate protections for Americans with preexisting conditions, place more red tape between families and their healthcare, and seize ideological trophies instead of focusing on making life more affordable. Americans will pay a steep price if Republicans move forward with this disastrous agenda.”

Richard Phillips, pensions and tax policy director for Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), marveled at the GOP loading up a bill supposedly focused on working families with massive giveaways to the wealthiest Americans.

"As part of it's new affordability agenda for the American people the Republican Study Committee reveals its plan to give the wealthiest 0.2% of estates a $281 billion tax break?" he wrote in a post on X.

Chuck Marr, vice president of federal tax policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, similarly called the GOP blueprint "tone deaf."

"Nothing says attack the affordability crisis working-class people face than Rs calling for eliminating the estate tax for the wealthiest heirs in the country—just months after giving them a $30 million tax free exemption," he wrote.

The GOP's second attempt at a budget reconciliation package comes months after it passed the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, a reconciliation package that gave more tax breaks to the rich, but cut Medicaid spending by nearly $1 trillion over the next decade, while also slashing spending on the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program by nearly $200 billion over the same period.