As Maria Carey and Wham once again dominate the airwaves, and another year comes to a close, let us consider whether 2023 was another year wasted in our fight against the sixth extinction or the year we turned a corner, as the mainstream media claim?

With only six years left to cut global CO2 emissions by

45% from 2010 levels, are we on track to meet the aspirations of the Paris Agreement, or are we heading for the near-term collapse of our Earth’s systems? In a similar vein, the 2022 Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework aims to halt and reverse biodiversity loss by 2030. Was 2023 the year we spared nature?

The first place to start will be global CO2 emissions. With 45% cuts necessary by 2030, we need our emissions to drop by 9.2% per year. Drum roll please… according to the Global Carbon Project, we added more than 40 billion tons of CO2 to our atmosphere and oceans, and our emissions, rather unsurprisingly, grew

1.1% to record levels. Methane and nitrous oxide emission forecasts are not yet in, but there is little reason to believe they will buck their long-term trend upward into the atmosphere—especially as it appears that a positive feedback loop may have been crossed with natural methane emissions rising between 2020 and 2023, potentially due to the three-year La Niña period, which saw increased rainfall in tropical wetlands.

The latest COP was proof of just how dysfunctional our response to these threats is. So, what can be done?

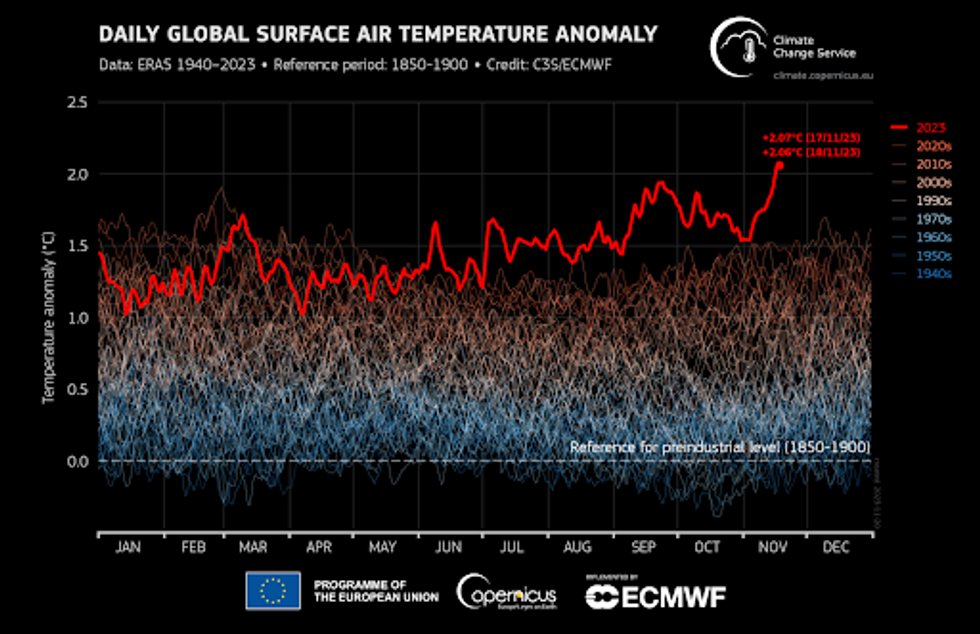

This year’s transition from La Niña into the warming El Niño phase gave us a glimpse of our future as we experienced record-breaking temperatures all over our planet. In 2023, around

one-third of days exceeded 2.7°F (1.5°C) of global average warming compared to the 1850-1900 period. Avoiding global average warming of 2.7°F (1.5°C) was the aspirational 2050 goal of the Paris agreement, yet we have passed this threshold for much of 2023, admittedly due to the temporary El Niño period. As if this wasn’t terrifying enough, just a month after this news broke, global average temperatures exceeded historical levels by over 3.62°F (2°C), while the main Paris agreement goal was to limit global average temperature rise to 3.62°F (2°C). All this adds up to 2023 becoming the hottest year on record. Global temperature records only began in 1880, but the European Union’s Copernicus Climate Change Service is “virtually certain” that 2023 will be the hottest year in 125,000 years, more than half the history of modern humans.

All this extra heat in our atmosphere, oceans, and soil has led to startling events this past year. Wildfires tore through Maui with at least 100 people killed. Canada saw 15.6 million hectares burned—leading to residents in the city that never sleeps literally wide-eyed due to smoke blanketing New York. Canada’s wildfire season was declared its worst on record; an area the size of England was incinerated. As Canada burned, California swapped its usual fiery summer season for its first tropical storm in 84 years, leaving 26 million people at risk of flooding.

Research from the Chinese Academy of Sciences warned that in addition to surface warming, the strong El Niño in 2023-2024 is “predicted to trigger a cascade of climate crises including marine heatwave intensification, ocean deoxygenation, damage to marine ecosystems, sea-level rise, crop yield reduction, and oceanic diversity reduction.” A report from the University of Exeter further warned that we are at risk of crossing five boundaries known as “tipping points” within the next decade. Crossing these boundaries could lead to abrupt or irreversible changes in the natural world and “severely damage our planet’s life-support systems and threaten the stability of our societies.” These systems are the Greenland and West Antarctic ice sheets, warm-water coral reefs, North Atlantic Subpolar Gyre circulation, and permafrost regions.

Even more alarming, if that is possible, was the news that the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), known as the Gulf Stream, could shut down completely by 2025. You would think the response to these reports would spur us into immediate far-reaching action, but we’ll get to that later. We are clearly failing on climate; what about biodiversity?

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has long been the gold standard when evaluating the percentage of species at risk of extinction. According to the IUCN, 28% of all assessed species are at risk: 41% of amphibians, 26% of mammals, 12% of birds, 37% of sharks and rays, 35% of corals, 21% of reptiles, and 34% of conifers.

If we are to avoid planetary turmoil, then we will need to stop being obedient and start to disobey those responsible for ruining our future in exchange for GDP growth.

A report from Queen’s University Belfast in May 2023 laid out the threat starkly. They focused on dynamic population trends in 71,000 animal species spanning mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fishes. Their findings showed that, of the species on the IUCN’s Red List listed as ‘non-threatened,’ 33% showed population declines. Globally, 48% of species were experiencing declines, 49% were stable, and 3% were increasing. Clearly, the 3% showing population increases are insufficient to replace those species in decline. This led the authors of the report to state: “Our study contributes a further signal indicating that global biodiversity is entering a mass extinction, with ecosystem heterogeneity and functioning, biodiversity persistence, and human well-being under increasing threat.”

Most of the declines are happening in the tropics, but 34% of plants and 40% of animals in the U.S. are at risk with 41% of ecosystems threatened by range-wide collapse. In the U.K., the situation proves what happens in the tropics won’t stay in the tropics. Here, around 16% of all species are at risk of extinction, and 43% of birds, 31% of reptiles, 26% of mammals, and 54% of flowering plant species are threatened. The annual Forest Declaration Assessment states we are 21% off target to halt deforestation by 2030. It appears we are failing badly on biodiversity too.

With economic development causing the climate and biodiversity crises we see, you would think our societies would be in fine fettle, but this is not the case. Although the rise in global gross domestic product has remained largely unchanged since the advent of neoliberalism in the late 1970s, homelessness has continued to rise; around 1.6 billion are living in poor housing with 15 million being forcibly evicted each year.

Another metric that is useful when evaluating our progress as a species is the number of mouths which go unfed each day. The number was declining year on year until 2015, leading Steven Pinker et al. to declare we had never had it so good. Fast forward to 2023, and the number of humans facing chronic hunger has risen sharply since 2015 to 783 million. This has nothing to do with scarcity. Each human being needs to eat 2,250 calories per day, and we currently grow 6,000 calories per person per day.

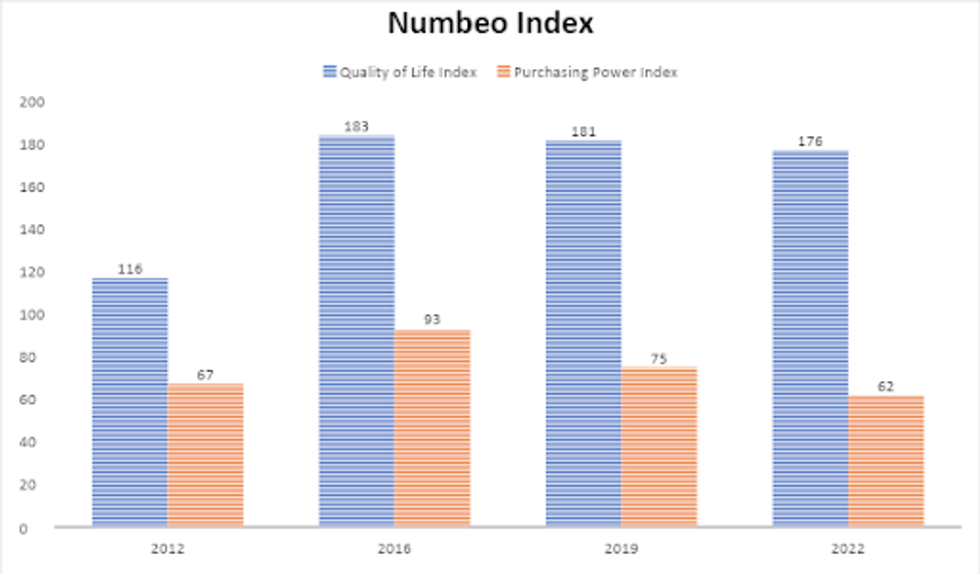

The Numbeo Index is another useful guide to human well-being. Ostensibly set up to compare the cost of living globally, it can also illuminate quality of life. The data showed positive progress until 2016, but since then things have declined. Purchasing power also dipped from 2016 to 2019, and by 2022 all the gains made from 2012 to 2016 had been erased.

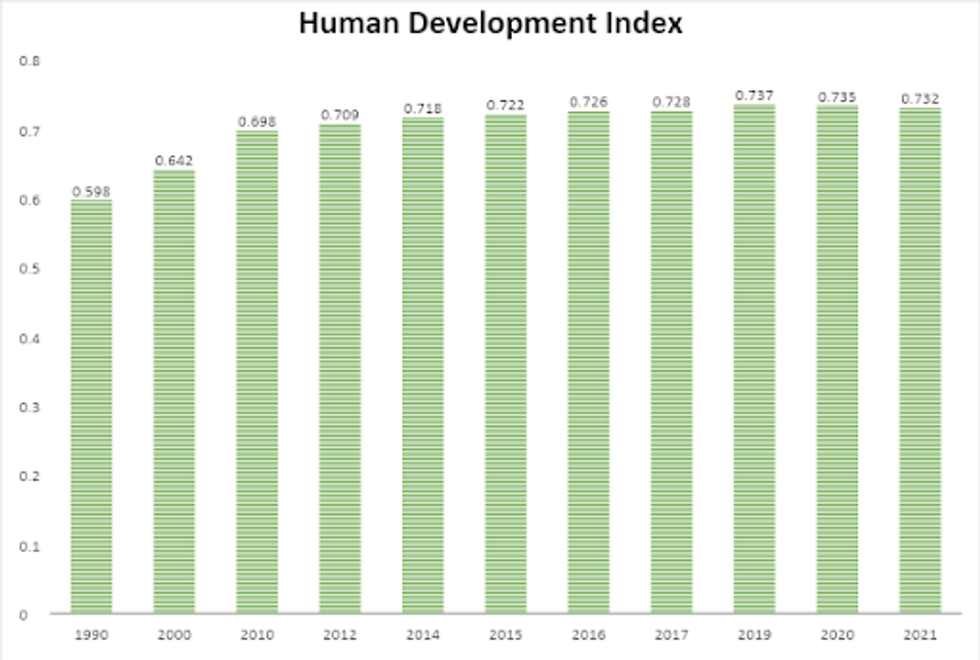

The United Nations Human Development Index (HDI) also saw a regression in 90% of countries in both 2020 and 2021—the latest data available. Many will attribute the decline to the pandemic, but, due to a lag from data collection to publication, much of the data for 2020 was collected in 2019, and the decline was underway before the pandemic hit.

While most of us on Earth have felt the pinch in recent years, some of us are doing better than ever. The fortunes of billionaires is increasing by $2.7 billion a day, and the richest 1% have grabbed almost two-thirds of new wealth since 2020—equaling $42 trillion, leaving the remaining third for the bottom 99%. The system isn’t broken: It’s working just as intended.

So, how have governments, aware of all this data and much more, attempted to tackle the existential threats we face? At the 28th installment of the Conference of the Parties (COP) this month in Dubai, our elected leaders finally agreed that “transitioning away from fossil fuels” was necessary. Elementary school children could have told us this at a fraction of the cost, and they wouldn’t have taken the best part of 30 years to decide this.

It is hardly surprising when you consider that COP28 was presided over by Sultan Ahmed Al Jaber: the boss of the state energy giant ADNOC. At the outset of the COP, he stated there was “no science” that showed we need to phase out fossil fuel use to limit warming to 1.5°C. It is understandable that he declared the outcome “a true victory for those who are sincere and genuine in helping address this global climate challenge” and “a true victory for those who are pragmatic, results-oriented, and led by the science.”

When it comes to the largest cause of biodiversity loss, massive “success” was enjoyed yet again. This time, the criterion for success was a bar so low that an ant would struggle to limbo underneath. Pundits were applauding the fact that agriculture was actually discussed at all at a COP—an industry responsible for a third of global emissions and the primary driver of biodiversity loss has thus far been ignored at all prior iterations of the COP franchise. That we are even able to discuss food is shocking considering that major players like chemical giant Bayer, meat supplier JBS, and fertilizer company Nutrien were all present in record numbers to prevent the changes we so badly need from occurring. The latest COP was proof of just how dysfunctional our response to these threats is. So, what can be done?

This is the million-dollar question that can provide an equal number of answers. What we can all be clear about is that ignoring the situation and “hoping” for change will result in nothing but complete climate chaos and the breakdown of our societies. Before that, we will also be complicit in the genocide of the

Global South, who are already badly affected by our lifestyles, apathy, and obedience. A few easy actions those of us in the industrialized world can do are change who we get our household energy from and change how we energize our bodies. Moving to

renewable energy suppliers and

plant-based diets could get us beyond the 45% cut we need by 2030. This will buy us time. Our governments, however, have shown that they are unable to offer us long-term security and have thus torn up the social contract between us. If we are to avoid planetary turmoil, then we will need to stop being obedient and start to disobey those responsible for ruining our future in exchange for GDP growth. One thing is certain: If 2024 is much the same as 2023, then we will be one year closer to extinction, not salvation.