There were about 250,000 slaves in Texas when it became the last state to release African American bodies from the cruelest institution known to American history.

Partial Freedom: What Juneteenth Looks Like for Prisoners Like Us

If our ancestors were able not only to survive but also sometimes thrive in the face of enslavers’ disregard for their humanity, so can we.

Juneteenth is a bittersweet day for Black people in prison holding onto the promise of freedom.

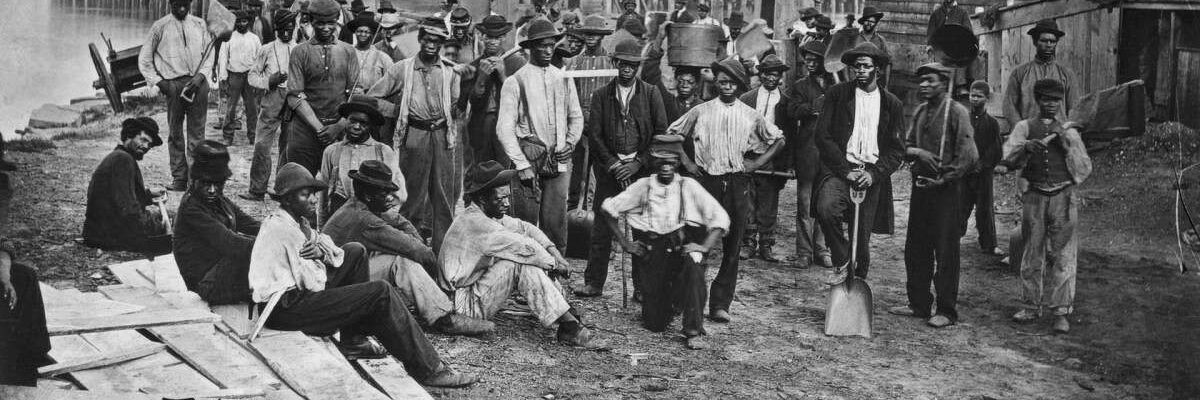

Let’s start with history. The Emancipation Proclamation—issued by Abraham Lincoln on September 22, 1862, during the American Civil War—declared that on January 1 all slaves in the Confederacy would be “forever free.” Unfortunately, that freedom didn’t extend to the four slaveholding states not in rebellion against the Union, and the proclamation was of course ignored by the Confederate states in rebellion. For the roughly 4 million people enslaved, Lincoln's declaration was symbolic; only after the Civil War ended was the proclamation enforced.

But the end of the fighting in April 1865 didn’t immediately end slavery everywhere. As the Union Army took control of more Confederate territory during the war, Texas became a safe haven for slaveholders. Finally, on June 19, Union General Gordon Granger rode into Galveston and issued General Order No. 3, announcing freedom for those enslaved.

The end of the fighting in April 1865 didn’t immediately end slavery everywhere.

There were about 250,000 slaves in Texas when it became the last state to release African American bodies from the cruelest institution known to American history. By the end of that year, the 13th Amendment abolished slavery, mostly (more on that soon).

Darrell Jackson: My understanding of Juneteenth developed in prison

Juneteenth has long been a special day in Black communities, but I didn’t learn about it until I went to prison.

In the early 2000s, prisoners at Washington State Penitentiary in Walla Walla decided to hold a Juneteenth celebration. Because the Department of Corrections didn’t treat the day as special, Black prisoners used the category of "African American Cultural Event" (which had usually been used to celebrate Black History Month) as a platform to celebrate Juneteenth. The spirit of liberation moved through the incarcerated population, motivating other prison facilities across the state to follow suit.

It seems hard to believe, but prior to my incarceration, I knew nothing about Juneteenth. I had taken classes that included American history, but the event apparently wasn’t part of my school's curriculum. I first heard about that history from other prisoners at Clallam Bay Correction Center, where I was incarcerated in 2009, and that prompted me to learn more about the ways that African Americans mark Juneteenth. By the time I had entered the prison system, Black prisoners had expanded the celebration to include family, friends, and community members, creating an opportunity for prisoners to connect with loved ones in ways that regular visiting did not permit. We were able to choose what foods we ate and provide our own entertainment, using creative ways to communicate inspiring messages to the African American prison population and their families.

One memorable moment for me came in June 2012. The Black Prisoners Caucus was hosting the event, which had not happened since 2007, and a friend and I were asked to perform a few songs. It was my first vocal performance and I was extremely nervous. When we finished, my friend's 7-year-old daughter shouted from the audience, "Daddy, they killed it!" Though I didn't have any family present at the event, that little girl's endorsement etched a long-lasting smile on my heart. Her words had become a soothing balm in the face of the stress, self-doubt, depression, and anger I had felt as a prisoner throughout that year.

It’s important for the world to know that Juneteenth holds great significance for the Black bodies who are locked away in prison. But we shouldn’t forget that the 13th Amendment abolished slavery and involuntary servitude, “except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.” For the men and women who are Black and in prison, that exception connects us to our ancestors who were in chains long ago.

Antoine Davis: The conflict of celebrating freedom while in chains

I can only imagine the effect that June 19, 1865, had on the souls of those trapped in the most barbaric institution in American history. The hope for freedom, passed down from one generation to another, had finally come to pass. Tears from Black faces must have run like rivers, not from the pains of a master's lashes but from the joy of knowing that one’s momma and daddy, sons and daughters, family and friends would no longer live in bondage.

Such images of joy have run through my mind as I have celebrated Juneteenth with Black families and White families, all occupying the same space in the prison's visiting room. While our loved ones laugh and dance, eat and rejoice, the truth about what we celebrate creates for me a tension between joy and grief. The joy comes from recognizing how far we've come as a people. The grief comes from the reminder that while chattel slavery was abolished, a new form continues in a prison system that incarcerates African American people at an alarming rate.

Prisoners aren’t the only people who understand the injustice. For several decades, activists and academics have developed an analysis called “Thirteentherism,” which argues that the 13th Amendment created constitutional protection for the brutal convict-leasing system that former Confederate states created after Reconstruction and which evolved into today’s system of racialized mass incarceration.

Here’s just one statistic of many: In Washington state, 33 percent of prisoners serving a sentence longer than 15 years for an offense committed before their 25th birthday are black. Blacks make up 4.3 percent of the state's population.

The statistics that demonstrate the racialized disparities in prisons make me think of Devontae Crawford, who at the age of 20 was sentenced to 35 years in prison. Although he committed a crime with three white friends, Devontae ended up with more time than all his crime partners put together. Today, all three of them are free, and Devontae still has 30 years left to do in prison.

One of my closest friends, who asked to remain anonymous, also comes to mind. He was sentenced to 170 years in prison after his white friend shot a man during an altercation. Although his friend admitted to being the gunman, this prisoner remains incarcerated while his white friend was released after serving seven years.

Jackson/Davis: Still slaves to the system

As Black men in prison, we live the tension between celebrating the abolition of slavery and struggling inside the criminal justice system that replaced slavery. We prisoners who are left to deteriorate inside one of America's most inhumane systems are able to find joy in celebrating Juneteenth, but not without indignities.

For example, a number of us were told by the DOC that prisoners would have to pay an estimated $1,500 for this year's Juneteenth celebration—$500 for food, not including the cost to our guests, and $1,000 to pay for additional guards. Juneteenth became a national holiday in 2021, and DOC officials decided that African American prisoners should cover the overtime and holiday pay for the extra guards deemed to be necessary for us to celebrate Juneteenth with our children.

That’s a lot of money for any working folks, but consider what it means for people who make 42 cents an hour, maxing out at $55 a month. No matter what the job in prison, that’s our DOC wage. This means that if we African American prisoners want to include our children in celebrating the historical meaning behind June 19, we will be forced to give the prison facility 3,600 hours of labor. The irony is hardly subtle: Prisoners in Washington state who work at near-slave wages will have to pay to celebrate a day that represents freedom.

We live with this injustice, but we African American prisoners find a way to maintain joy in the face of adversity. It's never easy to cope with the social conditions that are designed to diminish prisoners’ sense of their own value, but we keep on keeping on. If our ancestors were able not only to survive but also sometimes thrive in the face of enslavers’ disregard for their humanity, so can we. Something as simple as a 7-year-old girl shouting encouragement after a Juneteenth performance can be enough to keep us going.

African American prisoners have learned to embrace all the positives, celebrating freedom when we can while living in modern-day chains.An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Juneteenth is a bittersweet day for Black people in prison holding onto the promise of freedom.

Let’s start with history. The Emancipation Proclamation—issued by Abraham Lincoln on September 22, 1862, during the American Civil War—declared that on January 1 all slaves in the Confederacy would be “forever free.” Unfortunately, that freedom didn’t extend to the four slaveholding states not in rebellion against the Union, and the proclamation was of course ignored by the Confederate states in rebellion. For the roughly 4 million people enslaved, Lincoln's declaration was symbolic; only after the Civil War ended was the proclamation enforced.

But the end of the fighting in April 1865 didn’t immediately end slavery everywhere. As the Union Army took control of more Confederate territory during the war, Texas became a safe haven for slaveholders. Finally, on June 19, Union General Gordon Granger rode into Galveston and issued General Order No. 3, announcing freedom for those enslaved.

The end of the fighting in April 1865 didn’t immediately end slavery everywhere.

There were about 250,000 slaves in Texas when it became the last state to release African American bodies from the cruelest institution known to American history. By the end of that year, the 13th Amendment abolished slavery, mostly (more on that soon).

Darrell Jackson: My understanding of Juneteenth developed in prison

Juneteenth has long been a special day in Black communities, but I didn’t learn about it until I went to prison.

In the early 2000s, prisoners at Washington State Penitentiary in Walla Walla decided to hold a Juneteenth celebration. Because the Department of Corrections didn’t treat the day as special, Black prisoners used the category of "African American Cultural Event" (which had usually been used to celebrate Black History Month) as a platform to celebrate Juneteenth. The spirit of liberation moved through the incarcerated population, motivating other prison facilities across the state to follow suit.

It seems hard to believe, but prior to my incarceration, I knew nothing about Juneteenth. I had taken classes that included American history, but the event apparently wasn’t part of my school's curriculum. I first heard about that history from other prisoners at Clallam Bay Correction Center, where I was incarcerated in 2009, and that prompted me to learn more about the ways that African Americans mark Juneteenth. By the time I had entered the prison system, Black prisoners had expanded the celebration to include family, friends, and community members, creating an opportunity for prisoners to connect with loved ones in ways that regular visiting did not permit. We were able to choose what foods we ate and provide our own entertainment, using creative ways to communicate inspiring messages to the African American prison population and their families.

One memorable moment for me came in June 2012. The Black Prisoners Caucus was hosting the event, which had not happened since 2007, and a friend and I were asked to perform a few songs. It was my first vocal performance and I was extremely nervous. When we finished, my friend's 7-year-old daughter shouted from the audience, "Daddy, they killed it!" Though I didn't have any family present at the event, that little girl's endorsement etched a long-lasting smile on my heart. Her words had become a soothing balm in the face of the stress, self-doubt, depression, and anger I had felt as a prisoner throughout that year.

It’s important for the world to know that Juneteenth holds great significance for the Black bodies who are locked away in prison. But we shouldn’t forget that the 13th Amendment abolished slavery and involuntary servitude, “except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.” For the men and women who are Black and in prison, that exception connects us to our ancestors who were in chains long ago.

Antoine Davis: The conflict of celebrating freedom while in chains

I can only imagine the effect that June 19, 1865, had on the souls of those trapped in the most barbaric institution in American history. The hope for freedom, passed down from one generation to another, had finally come to pass. Tears from Black faces must have run like rivers, not from the pains of a master's lashes but from the joy of knowing that one’s momma and daddy, sons and daughters, family and friends would no longer live in bondage.

Such images of joy have run through my mind as I have celebrated Juneteenth with Black families and White families, all occupying the same space in the prison's visiting room. While our loved ones laugh and dance, eat and rejoice, the truth about what we celebrate creates for me a tension between joy and grief. The joy comes from recognizing how far we've come as a people. The grief comes from the reminder that while chattel slavery was abolished, a new form continues in a prison system that incarcerates African American people at an alarming rate.

Prisoners aren’t the only people who understand the injustice. For several decades, activists and academics have developed an analysis called “Thirteentherism,” which argues that the 13th Amendment created constitutional protection for the brutal convict-leasing system that former Confederate states created after Reconstruction and which evolved into today’s system of racialized mass incarceration.

Here’s just one statistic of many: In Washington state, 33 percent of prisoners serving a sentence longer than 15 years for an offense committed before their 25th birthday are black. Blacks make up 4.3 percent of the state's population.

The statistics that demonstrate the racialized disparities in prisons make me think of Devontae Crawford, who at the age of 20 was sentenced to 35 years in prison. Although he committed a crime with three white friends, Devontae ended up with more time than all his crime partners put together. Today, all three of them are free, and Devontae still has 30 years left to do in prison.

One of my closest friends, who asked to remain anonymous, also comes to mind. He was sentenced to 170 years in prison after his white friend shot a man during an altercation. Although his friend admitted to being the gunman, this prisoner remains incarcerated while his white friend was released after serving seven years.

Jackson/Davis: Still slaves to the system

As Black men in prison, we live the tension between celebrating the abolition of slavery and struggling inside the criminal justice system that replaced slavery. We prisoners who are left to deteriorate inside one of America's most inhumane systems are able to find joy in celebrating Juneteenth, but not without indignities.

For example, a number of us were told by the DOC that prisoners would have to pay an estimated $1,500 for this year's Juneteenth celebration—$500 for food, not including the cost to our guests, and $1,000 to pay for additional guards. Juneteenth became a national holiday in 2021, and DOC officials decided that African American prisoners should cover the overtime and holiday pay for the extra guards deemed to be necessary for us to celebrate Juneteenth with our children.

That’s a lot of money for any working folks, but consider what it means for people who make 42 cents an hour, maxing out at $55 a month. No matter what the job in prison, that’s our DOC wage. This means that if we African American prisoners want to include our children in celebrating the historical meaning behind June 19, we will be forced to give the prison facility 3,600 hours of labor. The irony is hardly subtle: Prisoners in Washington state who work at near-slave wages will have to pay to celebrate a day that represents freedom.

We live with this injustice, but we African American prisoners find a way to maintain joy in the face of adversity. It's never easy to cope with the social conditions that are designed to diminish prisoners’ sense of their own value, but we keep on keeping on. If our ancestors were able not only to survive but also sometimes thrive in the face of enslavers’ disregard for their humanity, so can we. Something as simple as a 7-year-old girl shouting encouragement after a Juneteenth performance can be enough to keep us going.

African American prisoners have learned to embrace all the positives, celebrating freedom when we can while living in modern-day chains.- Why Juneteenth Celebrations Should Acknowledge the 13th Amendment ›

- Opinion | The Holiday Season and Children’s Separation from Incarcerated Family Members | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | Juneteenth Was Not Freely Given—It Was Won | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | This Juneteenth, America Must Choose to Live Up to Its Founding Documents | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | Juneteenth and the Fight for Justice in Selma and Beyond | Common Dreams ›

Juneteenth is a bittersweet day for Black people in prison holding onto the promise of freedom.

Let’s start with history. The Emancipation Proclamation—issued by Abraham Lincoln on September 22, 1862, during the American Civil War—declared that on January 1 all slaves in the Confederacy would be “forever free.” Unfortunately, that freedom didn’t extend to the four slaveholding states not in rebellion against the Union, and the proclamation was of course ignored by the Confederate states in rebellion. For the roughly 4 million people enslaved, Lincoln's declaration was symbolic; only after the Civil War ended was the proclamation enforced.

But the end of the fighting in April 1865 didn’t immediately end slavery everywhere. As the Union Army took control of more Confederate territory during the war, Texas became a safe haven for slaveholders. Finally, on June 19, Union General Gordon Granger rode into Galveston and issued General Order No. 3, announcing freedom for those enslaved.

The end of the fighting in April 1865 didn’t immediately end slavery everywhere.

There were about 250,000 slaves in Texas when it became the last state to release African American bodies from the cruelest institution known to American history. By the end of that year, the 13th Amendment abolished slavery, mostly (more on that soon).

Darrell Jackson: My understanding of Juneteenth developed in prison

Juneteenth has long been a special day in Black communities, but I didn’t learn about it until I went to prison.

In the early 2000s, prisoners at Washington State Penitentiary in Walla Walla decided to hold a Juneteenth celebration. Because the Department of Corrections didn’t treat the day as special, Black prisoners used the category of "African American Cultural Event" (which had usually been used to celebrate Black History Month) as a platform to celebrate Juneteenth. The spirit of liberation moved through the incarcerated population, motivating other prison facilities across the state to follow suit.

It seems hard to believe, but prior to my incarceration, I knew nothing about Juneteenth. I had taken classes that included American history, but the event apparently wasn’t part of my school's curriculum. I first heard about that history from other prisoners at Clallam Bay Correction Center, where I was incarcerated in 2009, and that prompted me to learn more about the ways that African Americans mark Juneteenth. By the time I had entered the prison system, Black prisoners had expanded the celebration to include family, friends, and community members, creating an opportunity for prisoners to connect with loved ones in ways that regular visiting did not permit. We were able to choose what foods we ate and provide our own entertainment, using creative ways to communicate inspiring messages to the African American prison population and their families.

One memorable moment for me came in June 2012. The Black Prisoners Caucus was hosting the event, which had not happened since 2007, and a friend and I were asked to perform a few songs. It was my first vocal performance and I was extremely nervous. When we finished, my friend's 7-year-old daughter shouted from the audience, "Daddy, they killed it!" Though I didn't have any family present at the event, that little girl's endorsement etched a long-lasting smile on my heart. Her words had become a soothing balm in the face of the stress, self-doubt, depression, and anger I had felt as a prisoner throughout that year.

It’s important for the world to know that Juneteenth holds great significance for the Black bodies who are locked away in prison. But we shouldn’t forget that the 13th Amendment abolished slavery and involuntary servitude, “except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.” For the men and women who are Black and in prison, that exception connects us to our ancestors who were in chains long ago.

Antoine Davis: The conflict of celebrating freedom while in chains

I can only imagine the effect that June 19, 1865, had on the souls of those trapped in the most barbaric institution in American history. The hope for freedom, passed down from one generation to another, had finally come to pass. Tears from Black faces must have run like rivers, not from the pains of a master's lashes but from the joy of knowing that one’s momma and daddy, sons and daughters, family and friends would no longer live in bondage.

Such images of joy have run through my mind as I have celebrated Juneteenth with Black families and White families, all occupying the same space in the prison's visiting room. While our loved ones laugh and dance, eat and rejoice, the truth about what we celebrate creates for me a tension between joy and grief. The joy comes from recognizing how far we've come as a people. The grief comes from the reminder that while chattel slavery was abolished, a new form continues in a prison system that incarcerates African American people at an alarming rate.

Prisoners aren’t the only people who understand the injustice. For several decades, activists and academics have developed an analysis called “Thirteentherism,” which argues that the 13th Amendment created constitutional protection for the brutal convict-leasing system that former Confederate states created after Reconstruction and which evolved into today’s system of racialized mass incarceration.

Here’s just one statistic of many: In Washington state, 33 percent of prisoners serving a sentence longer than 15 years for an offense committed before their 25th birthday are black. Blacks make up 4.3 percent of the state's population.

The statistics that demonstrate the racialized disparities in prisons make me think of Devontae Crawford, who at the age of 20 was sentenced to 35 years in prison. Although he committed a crime with three white friends, Devontae ended up with more time than all his crime partners put together. Today, all three of them are free, and Devontae still has 30 years left to do in prison.

One of my closest friends, who asked to remain anonymous, also comes to mind. He was sentenced to 170 years in prison after his white friend shot a man during an altercation. Although his friend admitted to being the gunman, this prisoner remains incarcerated while his white friend was released after serving seven years.

Jackson/Davis: Still slaves to the system

As Black men in prison, we live the tension between celebrating the abolition of slavery and struggling inside the criminal justice system that replaced slavery. We prisoners who are left to deteriorate inside one of America's most inhumane systems are able to find joy in celebrating Juneteenth, but not without indignities.

For example, a number of us were told by the DOC that prisoners would have to pay an estimated $1,500 for this year's Juneteenth celebration—$500 for food, not including the cost to our guests, and $1,000 to pay for additional guards. Juneteenth became a national holiday in 2021, and DOC officials decided that African American prisoners should cover the overtime and holiday pay for the extra guards deemed to be necessary for us to celebrate Juneteenth with our children.

That’s a lot of money for any working folks, but consider what it means for people who make 42 cents an hour, maxing out at $55 a month. No matter what the job in prison, that’s our DOC wage. This means that if we African American prisoners want to include our children in celebrating the historical meaning behind June 19, we will be forced to give the prison facility 3,600 hours of labor. The irony is hardly subtle: Prisoners in Washington state who work at near-slave wages will have to pay to celebrate a day that represents freedom.

We live with this injustice, but we African American prisoners find a way to maintain joy in the face of adversity. It's never easy to cope with the social conditions that are designed to diminish prisoners’ sense of their own value, but we keep on keeping on. If our ancestors were able not only to survive but also sometimes thrive in the face of enslavers’ disregard for their humanity, so can we. Something as simple as a 7-year-old girl shouting encouragement after a Juneteenth performance can be enough to keep us going.

African American prisoners have learned to embrace all the positives, celebrating freedom when we can while living in modern-day chains.- Why Juneteenth Celebrations Should Acknowledge the 13th Amendment ›

- Opinion | The Holiday Season and Children’s Separation from Incarcerated Family Members | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | Juneteenth Was Not Freely Given—It Was Won | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | This Juneteenth, America Must Choose to Live Up to Its Founding Documents | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | Juneteenth and the Fight for Justice in Selma and Beyond | Common Dreams ›