SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

A dragonfly sits in reedbeds on the Isle of Grain on August 31, 2016 in Isle of Grain, England. (Photo: Dan Kitwood/Getty Images)

A collection of new scientific papers authored by 56 experts from around the world reiterates rising concerns about bug declines and urges people and governments to take urgent action to address a biodiversity crisis dubbed the "insect apocalypse."

"The Global Decline of Insects in the Anthropocene Special Feature," which includes an introduction and 11 papers, was published Monday in Proceedings of the National Academies of Sciences alongside a related news article. "Nature is under siege," the scientists warn. "Insects are suffering from 'death by a thousand cuts.'"

The set of studies--resulting from a symposium in St. Louis--comes as the body of research on insect declines has grown in recent years, leading to major assessments published in February 2019 and April 2020, as well as a roadmap released last January by 73 scientists detailing how to battle the "bugpocalypse."

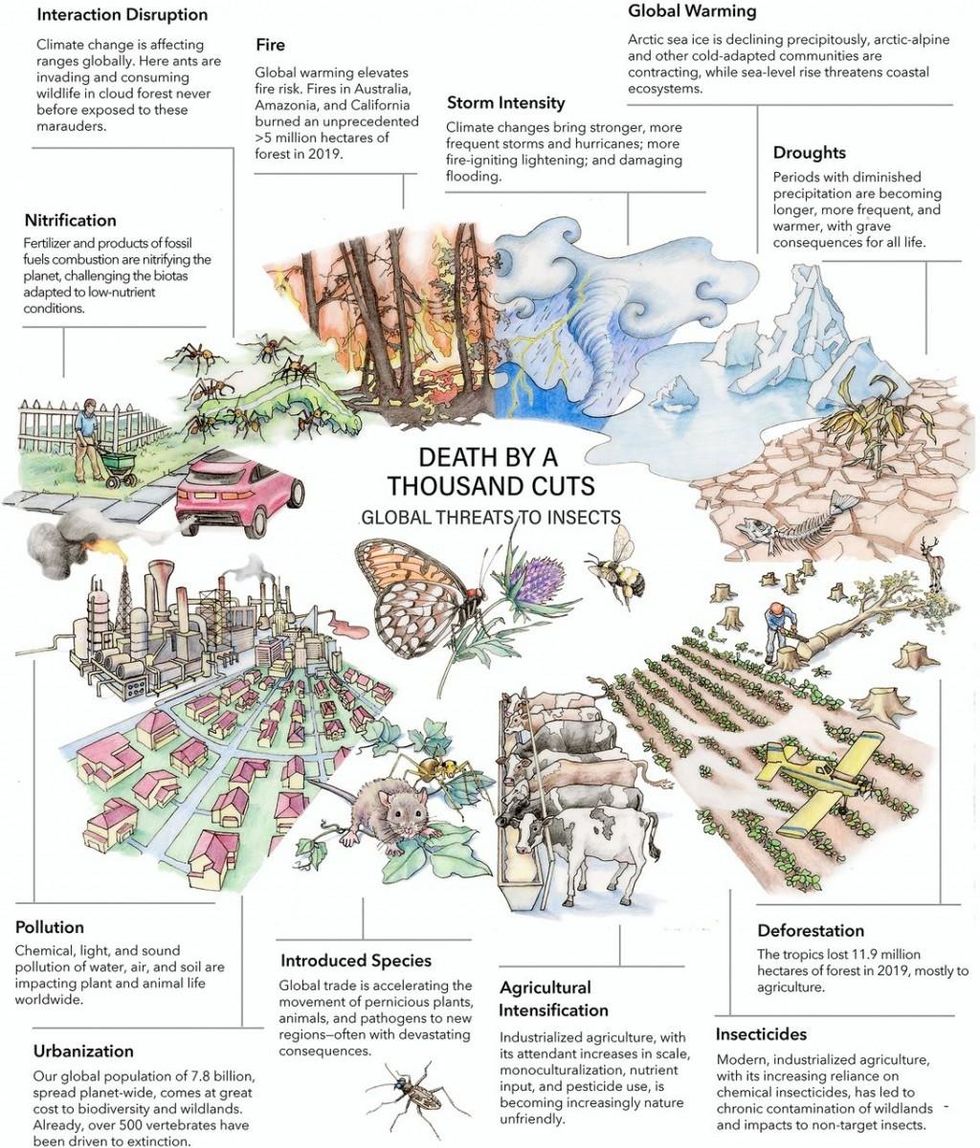

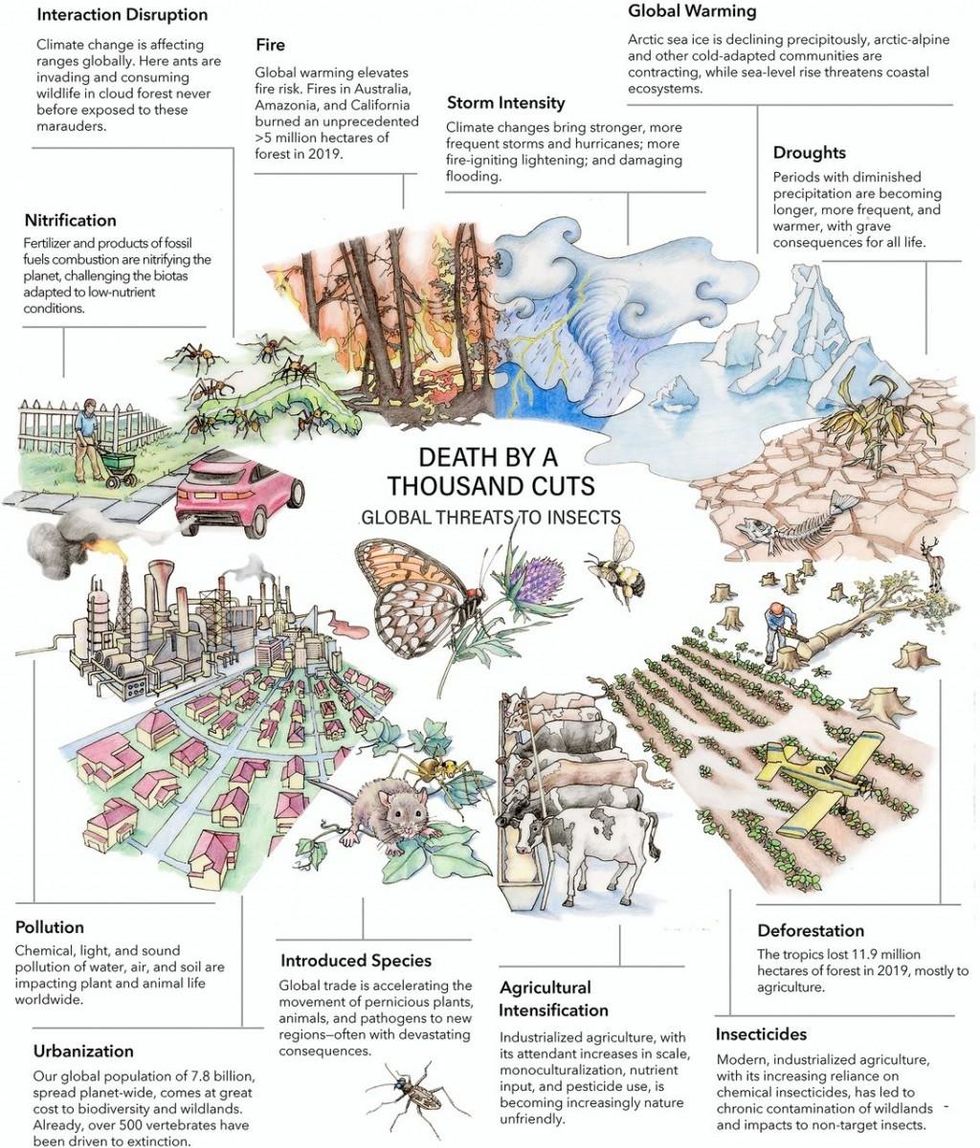

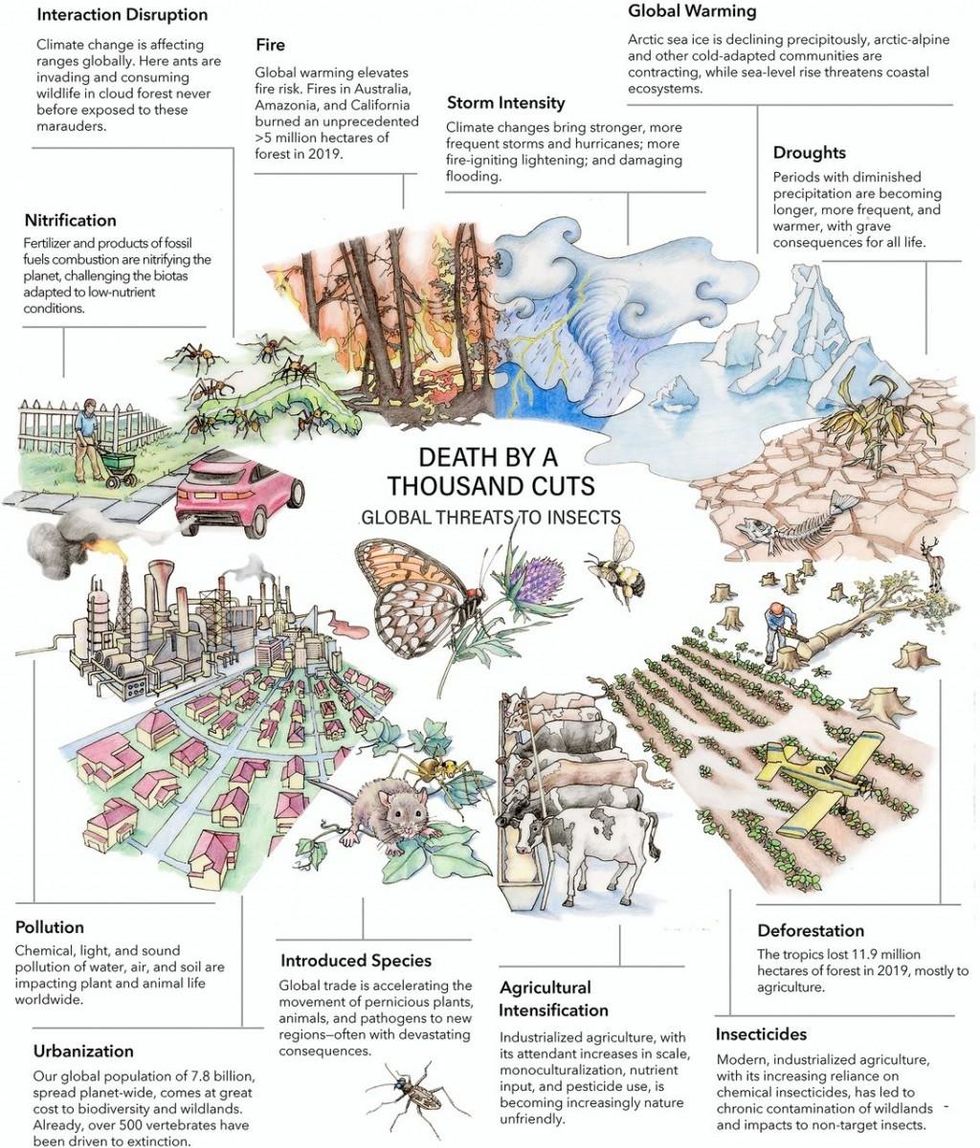

As the new package and below graphic explain, human stressors that experts have tied to bug declines include agricultural practices; chemical, light, and sound pollution; invasive species; land-use changes; nitrification; pesticides; and urbanization.

Emphasizing the consequences of such declines, University of Connecticut entomologist David Wagner, the package's lead author, told the Associated Press that insects "are absolutely the fabric by which Mother Nature and the tree of life are built."

According to Wagner, many insect populations are dropping about 1-2% per year. As he put it to The Guardian: "You're losing 10-20% of your animals over a single decade and that is just absolutely frightening. You're tearing apart the tapestry of life."

While most causes of declines are well known, "there's one really big unknown and that's climate change--that's the one that really scares me the most," he said, warning the crisis could be causing "extinctions at a rate that we haven't seen before."

Roel van Klink of the German Center for Integrative Biodiversity Research told The Guardian that "the most important thing we learn [from these new studies] is the complexity behind insect declines. No single quick fix is going to solve this problem."

"There are certainly places where insect abundances are dropping strongly, but not everywhere," he said. "This is a reason for hope, because it can help us understand what we can do to help them. They can bounce back really fast when the conditions improve."

The package's introduction points out that while much recent research and resulting news coverage focused on drops in bug populations, "four papers in this special issue note instances of insect lineages that have not changed or have increased in abundance."

"Many moth species in Great Britain have demonstrably expanded in range or population size," the paper notes. "Numerous temperate insects, presumably limited by winter temperatures, have increased in abundance and range, in response to warmer global temperatures."

Pollinators such as the western honey bee in North America, "may well thrive due to their associations with humans," the introduction adds. "Increasing abundances of freshwater insects have been attributed to clean water legislation, in both Europe and North America."

In addition to the introduction, titled "Insect decline in the Anthropocene: Death by a thousand cuts," the package includes seven perspectives:

The body of work also includes three separate research articles:

The final piece is an opinion laying out "eight simple actions that individuals can take to save insects from global declines," which features five actions to create "more and better insect-friendly habitats, the loss of which is likely a leading cause of insect declines," and three that aim to adjust public attitudes.

As Dharna Noor wrote in her coverage for Earther: "I do not like bugs. Creepy, many-legged things make my skin crawl. But as unpleasant as they are, insects are absolutely crucial for our world's ecosystems to function, and sadly, new research shows that the creatures populations are on the verge of collapse."

To boost awareness and appreciation of insects, the scientists suggest countering negative perceptions, pushing for conservation efforts, and getting involved in local political advocacy. On the habitat improvement front, they recommend converting lawns into diverse natural habitats, growing native plants, cutting pesticide use, limiting light pollution, and lessening soap runoff from washing vehicles and building exteriors as well as the use of driveway sealants and de-icing salts.

"Avoiding some behaviors or adopting others will contribute both directly and indirectly to insect conservation," the scientists note. "Further, taking actions that address issues such as climate change can synergistically promote insect diversity. Climate change is increasingly recognized as a primary factor driving local and regional plant and animal extinctions."

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

A collection of new scientific papers authored by 56 experts from around the world reiterates rising concerns about bug declines and urges people and governments to take urgent action to address a biodiversity crisis dubbed the "insect apocalypse."

"The Global Decline of Insects in the Anthropocene Special Feature," which includes an introduction and 11 papers, was published Monday in Proceedings of the National Academies of Sciences alongside a related news article. "Nature is under siege," the scientists warn. "Insects are suffering from 'death by a thousand cuts.'"

The set of studies--resulting from a symposium in St. Louis--comes as the body of research on insect declines has grown in recent years, leading to major assessments published in February 2019 and April 2020, as well as a roadmap released last January by 73 scientists detailing how to battle the "bugpocalypse."

As the new package and below graphic explain, human stressors that experts have tied to bug declines include agricultural practices; chemical, light, and sound pollution; invasive species; land-use changes; nitrification; pesticides; and urbanization.

Emphasizing the consequences of such declines, University of Connecticut entomologist David Wagner, the package's lead author, told the Associated Press that insects "are absolutely the fabric by which Mother Nature and the tree of life are built."

According to Wagner, many insect populations are dropping about 1-2% per year. As he put it to The Guardian: "You're losing 10-20% of your animals over a single decade and that is just absolutely frightening. You're tearing apart the tapestry of life."

While most causes of declines are well known, "there's one really big unknown and that's climate change--that's the one that really scares me the most," he said, warning the crisis could be causing "extinctions at a rate that we haven't seen before."

Roel van Klink of the German Center for Integrative Biodiversity Research told The Guardian that "the most important thing we learn [from these new studies] is the complexity behind insect declines. No single quick fix is going to solve this problem."

"There are certainly places where insect abundances are dropping strongly, but not everywhere," he said. "This is a reason for hope, because it can help us understand what we can do to help them. They can bounce back really fast when the conditions improve."

The package's introduction points out that while much recent research and resulting news coverage focused on drops in bug populations, "four papers in this special issue note instances of insect lineages that have not changed or have increased in abundance."

"Many moth species in Great Britain have demonstrably expanded in range or population size," the paper notes. "Numerous temperate insects, presumably limited by winter temperatures, have increased in abundance and range, in response to warmer global temperatures."

Pollinators such as the western honey bee in North America, "may well thrive due to their associations with humans," the introduction adds. "Increasing abundances of freshwater insects have been attributed to clean water legislation, in both Europe and North America."

In addition to the introduction, titled "Insect decline in the Anthropocene: Death by a thousand cuts," the package includes seven perspectives:

The body of work also includes three separate research articles:

The final piece is an opinion laying out "eight simple actions that individuals can take to save insects from global declines," which features five actions to create "more and better insect-friendly habitats, the loss of which is likely a leading cause of insect declines," and three that aim to adjust public attitudes.

As Dharna Noor wrote in her coverage for Earther: "I do not like bugs. Creepy, many-legged things make my skin crawl. But as unpleasant as they are, insects are absolutely crucial for our world's ecosystems to function, and sadly, new research shows that the creatures populations are on the verge of collapse."

To boost awareness and appreciation of insects, the scientists suggest countering negative perceptions, pushing for conservation efforts, and getting involved in local political advocacy. On the habitat improvement front, they recommend converting lawns into diverse natural habitats, growing native plants, cutting pesticide use, limiting light pollution, and lessening soap runoff from washing vehicles and building exteriors as well as the use of driveway sealants and de-icing salts.

"Avoiding some behaviors or adopting others will contribute both directly and indirectly to insect conservation," the scientists note. "Further, taking actions that address issues such as climate change can synergistically promote insect diversity. Climate change is increasingly recognized as a primary factor driving local and regional plant and animal extinctions."

A collection of new scientific papers authored by 56 experts from around the world reiterates rising concerns about bug declines and urges people and governments to take urgent action to address a biodiversity crisis dubbed the "insect apocalypse."

"The Global Decline of Insects in the Anthropocene Special Feature," which includes an introduction and 11 papers, was published Monday in Proceedings of the National Academies of Sciences alongside a related news article. "Nature is under siege," the scientists warn. "Insects are suffering from 'death by a thousand cuts.'"

The set of studies--resulting from a symposium in St. Louis--comes as the body of research on insect declines has grown in recent years, leading to major assessments published in February 2019 and April 2020, as well as a roadmap released last January by 73 scientists detailing how to battle the "bugpocalypse."

As the new package and below graphic explain, human stressors that experts have tied to bug declines include agricultural practices; chemical, light, and sound pollution; invasive species; land-use changes; nitrification; pesticides; and urbanization.

Emphasizing the consequences of such declines, University of Connecticut entomologist David Wagner, the package's lead author, told the Associated Press that insects "are absolutely the fabric by which Mother Nature and the tree of life are built."

According to Wagner, many insect populations are dropping about 1-2% per year. As he put it to The Guardian: "You're losing 10-20% of your animals over a single decade and that is just absolutely frightening. You're tearing apart the tapestry of life."

While most causes of declines are well known, "there's one really big unknown and that's climate change--that's the one that really scares me the most," he said, warning the crisis could be causing "extinctions at a rate that we haven't seen before."

Roel van Klink of the German Center for Integrative Biodiversity Research told The Guardian that "the most important thing we learn [from these new studies] is the complexity behind insect declines. No single quick fix is going to solve this problem."

"There are certainly places where insect abundances are dropping strongly, but not everywhere," he said. "This is a reason for hope, because it can help us understand what we can do to help them. They can bounce back really fast when the conditions improve."

The package's introduction points out that while much recent research and resulting news coverage focused on drops in bug populations, "four papers in this special issue note instances of insect lineages that have not changed or have increased in abundance."

"Many moth species in Great Britain have demonstrably expanded in range or population size," the paper notes. "Numerous temperate insects, presumably limited by winter temperatures, have increased in abundance and range, in response to warmer global temperatures."

Pollinators such as the western honey bee in North America, "may well thrive due to their associations with humans," the introduction adds. "Increasing abundances of freshwater insects have been attributed to clean water legislation, in both Europe and North America."

In addition to the introduction, titled "Insect decline in the Anthropocene: Death by a thousand cuts," the package includes seven perspectives:

The body of work also includes three separate research articles:

The final piece is an opinion laying out "eight simple actions that individuals can take to save insects from global declines," which features five actions to create "more and better insect-friendly habitats, the loss of which is likely a leading cause of insect declines," and three that aim to adjust public attitudes.

As Dharna Noor wrote in her coverage for Earther: "I do not like bugs. Creepy, many-legged things make my skin crawl. But as unpleasant as they are, insects are absolutely crucial for our world's ecosystems to function, and sadly, new research shows that the creatures populations are on the verge of collapse."

To boost awareness and appreciation of insects, the scientists suggest countering negative perceptions, pushing for conservation efforts, and getting involved in local political advocacy. On the habitat improvement front, they recommend converting lawns into diverse natural habitats, growing native plants, cutting pesticide use, limiting light pollution, and lessening soap runoff from washing vehicles and building exteriors as well as the use of driveway sealants and de-icing salts.

"Avoiding some behaviors or adopting others will contribute both directly and indirectly to insect conservation," the scientists note. "Further, taking actions that address issues such as climate change can synergistically promote insect diversity. Climate change is increasingly recognized as a primary factor driving local and regional plant and animal extinctions."