The big Wall Street banks have all talked a good line about supporting the Black Lives Matter movement. But that was never going to be enough for racial justice advocates.

"Stating commitments without accountability and transparency does not dismantle systemic racism," said Marc Bayard, director of the Black Worker Initiative at the Institute for Policy Studies.

Bayard is part of a coalition pushing Wall Street banks to submit to independent examinations of the impact of their policies and practices on racial inequality.

Big Wall Street banks have largely abandoned poor people of color, forcing them to rely on payday lenders and other small predatory financial firms.

The financial industry has a long history of racism, and even though protections against redlining and other discriminatory practices have been on the books for decades, the problems persist.

In fact, big Wall Street banks have largely abandoned poor people of color, forcing them to rely on payday lenders and other small predatory financial firms. According to an FDIC survey, 13.8 percent of Black households and 12.2 percent of Latino households did not have bank accounts in 2019, compared to just 2.5 percent of white households.

Another study found that for every $1 loaned out to finance residential properties in white neighborhoods in Chicago from 2012-2018, a mere 12 cents was invested in Black neighborhoods.

This spring, two labor union-related institutional investors gave executives at seven big Wall Street banks a big opportunity to show they're serious about changing course on racial inequality.

CtW Investment Group, which advises unions affiliated with the Change to Win federation, and the SEIU pension fund filed shareholder proposals asking the banks to engage civil rights organizations, employees, shareholders, and customers in a racial equity audit process. The goal: identifying and remedying the adverse impacts of bank policies and practices on non-white stakeholders and communities of color.

But instead of embracing the audit idea, all but one of the banks urged shareholders to reject the proposals.

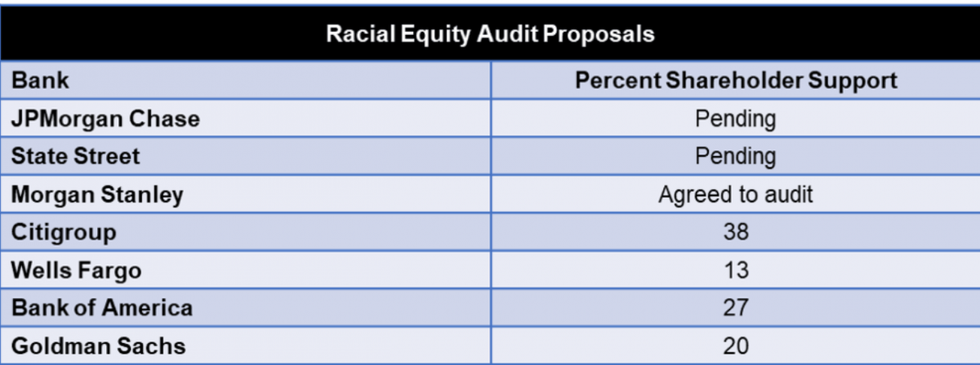

How have shareholders responded? Thus far, four of the seven banks (Bank of America, Wells Fargo, Citigroup, and Goldman Sachs) have held their annual meetings. And while none of the audit proposals received majority votes, sizeable minorities backed the idea, putting pressure on management to take notice.

A 38 percent "yes" vote at Citi was particularly encouraging, given the fact that institutional investors typically follow the corporate board's recommendation. Shareholders at JPMorgan Chase and State Street hold their meetings this week. CtW dropped the Morgan Stanley proposal after the bank agreed to conduct a racial equity audit.

Why did nearly all of the banks urge "no" votes on the audit proposals? In SEC filings, the banks argued that such analysis was unnecessary given the enormous strides they're already making on racial equity.

"Conducting a racial equity audit at this point in time would not provide us with useful additional information," states the JPMorgan proxy statement. "We believe our shareholders would be better served by the Firm's vigilant focus on building on current momentum to maintain a culture of respect and inclusion and advance racial equity."

That same proxy statement revealed that JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon earned $32 million in compensation last year. Like the chief executives of all seven of the banks in 2020, Dimon is a white man. (Jane Fraser, a white woman, took the helm of Citi in February 2021.)

Across the financial sector, the upper echelons are overwhelmingly white. At the five largest U.S. investment banks, the share of senior executives and top managers who are white ranges from 71 to 83 percent. (JPMorgan Chase: 81%, Goldman Sachs: 77%, Bank of America: 81%, Morgan Stanley: 83%, and Citigroup: 71%)

Nationwide, employees in the lucrative securities industry are 80.5 percent white, 5.8 percent Black, 11.5 percent Asian, and 8.1 percent Latino. Average pay in that industry (including bonus) was nearly $600,000 in 2019. By contrast, whites make up an estimated 55.4 percent of people in jobs that pay less than $15 per hour.

In a letter to JPMorgan CEO Dimon, the groups Transform Finance, Activest, Worth Rises, the Action Center on Race and the Economy (ACRE), the Institute for Policy Studies, and Public Accountability Initiative joined other racial justice organizations in supporting the racial equity audit proposal before JPMorgan, demanding "a commitment to long-term tangible change."

"Without a comprehensive investigation of how institutionalized racism impacts policies and business practices at these banks," says Bayard of IPS, "all their public commitments to equity will amount to empty promises."