Late last month, the latest round of United States sanctions, known as the Caesar Act, took effect against Syria, a country already in a dire situation after nine years of war and sanctions. Covid-19 and an economic crisis in Lebanon, a financial lifeline for Syrian civilians that the US has largely severed (CBS, 6/18/20), have exacerbated Syria's plight.

US media coverage has endorsed, downplayed or ignored the harm the sanctions will inflict on Syria's civilian population, and the misery years of previous sanctions have already inflicted.

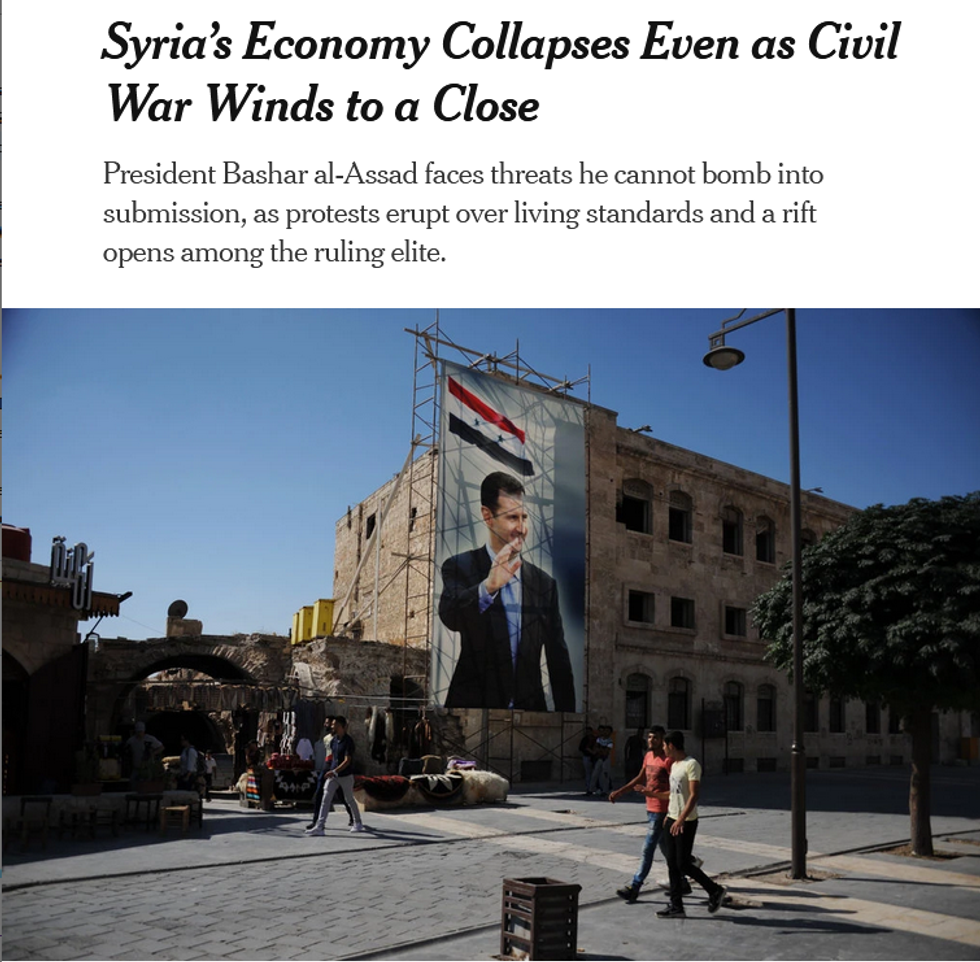

An article in the New York Times (6/15/20) noted that Syria has "an acute economic crisis" and that the Caesar Act is "likely to make matters worse," but it gives no indication that already-existing sanctions are part of that economic crisis. Reporter Ben Hubbard writes as though sanctions harming Syrians were a hypothetical possibility. For example, the article said that "last week the Syrian pound fell to 3,500 to the dollar on the black market," and that "prices for imported staples such as sugar, coffee, flour and rice have doubled or tripled," without connecting these problems to the economic war against the country.

Yet, as far back as 2012, the Danish Institute for International Studies, commissioned by the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, compiled a report that examined the effects of sanctions in place up to that point. It found that they "come at a significant socioeconomic cost to the Syrian population":

Complying and over-complying with the sanctions, international financial institutions have been highly reluctant to service Syrian nationals. This has indiscriminately presented all citizens and private businesses with bank accounts and credit cards with difficulties in performing international transactions, including transfers of remittances from abroad and external trade. As a result, private sector import and export of all types of products has been negatively affected....

As such, the sanctions have contributed to the substantial inflation that the Syrian economy is experiencing. Furthermore, by having a negative impact on the general economic activity and reducing the international confidence in the Syrian economy, the sanctions have indirectly contributed to the increasing unemployment rates, decreasing salary levels and thus the fall in purchasing power. The significant decline in purchasing power has, for example, eroded access to food across the country, though food commodities are available outside areas directly affected by the violence. Thus, through second-order effects, the sanctions add to the socioeconomic costs of the conflict and are likely to exacerbate pre-existing socioeconomic difficulties, particularly affecting the lower social strata of the population.

Therefore, while the Caesar Act is "likely to make matters worse," years of having sanctions in place is an important factor behind the "acute economic crisis" to which the Times points.

The Wall Street Journal (6/17/20) ran the absurd headline, "US Hits Assad Family With 'Caesar Act' Sanctions," as if the sanctions aim at one family rather than at decimating the country's economy. However, the wording of the legislation--which was folded into the National Defense Authorization Act for 2020--makes clear that it is intended to have far-reaching effects. It says that the US president will impose sanctions on a "foreign person" if they undertake actions that include knowingly

sell[ing] or provid[ing] significant goods, services, technology, information or other support that significantly facilitates the maintenance or expansion of the Government of Syria's domestic production of natural gas, petroleum or petroleum products.

Targeting Syria's oil and gas industries amounts to targeting the Syrian population; at the peak of pre-war production, oil generated about a quarter of government revenues (New Yorker, 10/30/19)--revenues that pay for health, education, pensions, water, electricity, and food and fuel subsidies, as even a State Department-funded outlet documents (Syria Direct, 3/18/20).

The Journal wrote that the Caesar Act "marked the first action under new powers meant to punish the regime's supporters." Even if one were to accept the untenable premise that the US has the right to punish "the regime's supporters" in countries of its choosing, the act punishes the Syrian population as a whole. The act says that the US president will impose sanctions on a "foreign person" if they "knowingly, directly or indirectly, provid[e] significant construction or engineering services to the Government of Syria." It goes on to explain that part of its "strategy" is to "deter foreign persons from entering into contracts related to reconstruction in the areas" under control of the Syrian government or its supporters from Russia and Iran, which is the vast majority of Syria. It's hard to read these clauses as anything other than attempts to ensure that this devastated country isn't rebuilt, and that Syrians have to live amid ruin irrespective of whether they are "the regime's supporters."

The Washington Post (6/23/20) published an editorial on the Caesar Act with a loaded headline of its own: "Syria's Brutal Dictatorship Suffers a Severe Setback." How could anyone not support a policy that deals a "severe setback" to such a government? It doesn't trouble the paper that this blow is being dealt by instituting more of the sanctions that have made it nearly impossible to import medical instruments and other medical supplies, and that have led to shortages of medicine.

The Post's editorial board endorses the Caesar Act, not despite its collective punishment of Syria but because of it, writing that the Syrian government's prospects of

reconstructing the economy have suffered a severe setback.... For that, some credit is due to Congress, which mandated the new economic sanctions in last year's defense bill.

Applauding US lawmakers for trying to prevent the Syrian government from "reconstructing" the disastrous economic situation in the country is akin to applauding them for seeking to maximize the pain felt by Syrians, since everyone who lives in Syria--and many Syrians who live outside of it--is necessarily affected by the country's economy.

The paper noted that "the mere prospect of [the Caesar Act] already helped crash the Syrian currency," as "the squeeze on average Syrians has led to renewed unrest in towns such as Daraa." The Post could have added that "the squeeze on average Syrians" has also led to Syrian children with cancer being unable to obtain necessary medicines (Reuters, 3/15/17).

Foreign Policy (6/17/20) ran an equally enthusiastic endorsement of blockading the largely destroyed country. Authors David Adesnik and Toby Dershowitz, both of the neoconservative Foundation for Defense of Democracies, contended that humanitarian provisions for Syria from the US and Europe belie the claim that the sanctions are cruel.

The argument that humanitarian provisions outweigh the burden that sanctions place on the Syrian masses is difficult to defend given that major humanitarian organizations operating in Syria have identified the sanctions as a cause of the country's pain. For example, in 2013, Medecins Sans Frontieres reported:

Before this conflict, Syria had a well-functioning health system. The country has trained health workers, medical expertise and a pharmaceutical industry. But today resources are depleted. Health networks are breaking down because of supply problems and drug shortages resulting from the collapse of the pharmaceutical industry, or indirectly from international sanctions imposed on Syria.

Similarly, in April 2020, the Red Crescent said that the sanctions were combining with the effects of war and a regional economic downturn to "generat[e] further hardship for many vulnerable Syrians."

Adesnik and Dershowitz's argument has already aged poorly. A mere ten days after their article was published, and after the Caesar Act went into effect, the Red Crescent reported:

The Covid-19 pandemic and recent harsher economic sanctions have exacerbated humanitarian needs, making the situation more untenable than ever before, for civilians with no stake to the conflict.

The corporate media discussed here, however, would rather keep US citizens in the dark about such injustices--when, that is, these outlets aren't actually calling for "saving" Syrians by denying them food and medicine.