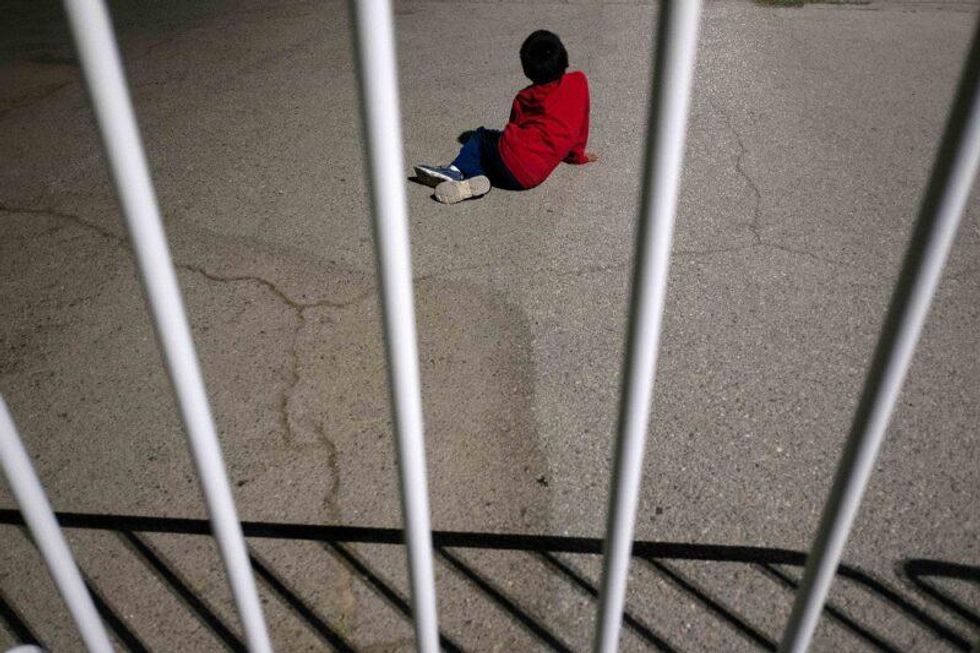

Asylum-seekers inside the Leona Vicario Federal shelter in Ciudad Juarez, October 9, 2019. (Photo: Guillermo Arias for the ACLU)

I Went to Mexico to Meet Asylum-Seekers Trapped at the Border. This Is What I Saw.

How will we respond to their suffering? Will we allow the most hateful and uncaring among us to write our history, or will we fight back and demand better?

Two weeks ago, I traveled to northern Mexico along with Mexican photographer Guillermo Arias to meet with asylum-seekers who've been trapped at the southern U.S. border by Trump Administration policies. Neither of us was prepared for what we saw there.

We visited two cities - Ciudad Juarez and Matamoros--to track down people who had been placed into the deceptively misnamed "Migrant Protection Protocols" that have slammed America's door shut to people fleeing persecution and violence in their home countries. Before we arrived, we wondered whether the stories we'd read of kidnappings, assaults, and despair were as widespread as they sounded. It didn't take long for us to get our answer.

There is--right now, at this very moment--a humanitarian crisis unfolding at our southern border. And we are not paying enough attention to it.

First, a little context. The Trump Administration has been waging an all-out war on the U.S.'s asylum system, which for more than 50 years has provided shelter for people who need protection. To accomplish this reversal of tradition, they've put into place a series of policies that have made it nearly impossible for people to quickly and safely claim asylum at the southern border. Chief among them is the forced return to Mexico program, which has trapped tens of thousands of people in dangerous cartel-controlled cities in northern Mexico while they wait for distant court dates inside the U.S.

The circumstances these vulnerable people are facing in the meantime are dire. We saw them first-hand.

Everywhere we went, people told us stories of being kidnapped or extorted while stuck in Mexico. Many were sleeping in tent encampments on the streets while safety across the border was literally within sight, but legally out of reach. Some were packed into shelters set up by the Mexican government, sleeping shoulder-to-shoulder on thin mattresses on the floor of converted warehouses. Others were living in privately-run shelters with no security protocols to prevent intruders from intimidating or preying on them.

Matamoros is a small city right across the Rio Grande from Brownsville, Texas, just along the coast of the Gulf of Mexico. It's in the Mexican state of Tamaulipas, where corruption and cartel-related violence is so bad that the U.S. state department has given it the same travel advisory as Afghanistan and Somalia. It's also become home to thousands of people who've fled Central America, South America, the Caribbean, Africa, and other parts of Mexico searching for safety.

Previously, they would have been processed through the asylum system and then either detained or released inside the U.S. while their claims were evaluated by an immigration judge. But now, they're given a sheet of paper that tells them to come back to the border months later for their first hearing. In the meantime, they're stuck, with nowhere to go and most often nobody to help them. Next to the Matamoros-Brownsville bridge, a tent camp has sprung up on a patch of pavement and dirt that around 2,000 asylum-seekers call home. The camp is growing every day.

The night before we visited, a storm system had swept through Texas, flooding the inside of the low-quality tents people were living in with rain. There was mud everywhere, and it was cold. Few people had the clothing to cope with the chilly temperatures, and the first few people we talked to were shivering, their teeth chattering as they spoke. Everywhere we looked, there were very young children sitting on curbs or hanging onto their parents.

One young man told us that in a tent nearby there was a Honduran woman with a newborn baby, so we stopped in to visit them. She'd delivered just five days earlier. Only 21 years old herself, she'd been living in the tent with her four-year-old daughter since being sent back to Matamoros by Customs and Border Protection agents. She said that when she'd first told CBP officers that she was pregnant, they suggested she get an abortion before telling her to come back for a court date over a month in the future.

The tiny child was bundled into blankets in the small tent where it was spending its first days of life. Her mother coughed when she spoke, visibly exhausted. She said that she'd fled an abusive spouse and was too afraid to return to him. Later, one of the few health responders who visits the camp regularly told me that she was fearful about whether the child would survive conditions at the camp, which she said reminded her of refugee camps she'd worked at in Bangladesh.

"If there's a cholera outbreak here, half of them could die," she said.

Further up the hill next to the camp, along a wooded grove, lies the Rio Grande. There are a few makeshift showers near the camp, but they aren't nearly enough for the entire camp to bathe, so many choose to wash and do their laundry at the bank of the river. The river is rife with pollution, and people living in the camp have developed rashes and other skin problems from bathing in it. Next to a small, muddy clearing, a series of white crosses stood in remembrance of the children who've died by drowning in the river in recent months.

A few nights before we visited the camp in Matamoros, some of its frustrated residents had staged a protest against conditions in the camp and the policies that have trapped them there, shutting down the bridge for 15 hours. "They keep telling us we have to wait longer and longer," one told Buzzfeed News. "When will it end?"

Walking among the tents and meeting their gracious and welcoming occupants, I felt the weight of my country's responsibility for their suffering. The insecurity, desperation, and discomfort of the people we were speaking with isn't a corollary effect of the policy, it's the core intent. The "Migrant Protection Protocols" were designed to make it so uncomfortable and dangerous for people who are seeking asylum that they will simply give up, exhausted and defeated, and return back to the dangerous situations they fled.

Many have, indeed, already done so.

Further along the border, in Ciudad Juarez, we visited a network of shelters that have been set up in recent months to cope with the roughly 17,000 asylum-seekers who've been returned there since mid-April. On one side of the spectrum was the newly-opened federal shelter, supervised by the Mexican government, which was housing over 500 people the week we were there. A converted warehouse with no individual rooms, people were sleeping on rows and rows of small mattresses lined up against the walls and across the middle of the large hall. Its inhabitants were there waiting for court hearings as far out as January of next year.

We met with Venezuelans who'd fled the political crisis in their country and El Salvadorans who spoke of witnessing family members gunned down in front of them. People told us they'd been dropped off on darkened streets in Juarez by Customs and Border Protection with no idea where to go or what to do. One parent told us she'd had to wrestle with a man who tried to abduct her daughter in front of her. Some spoke of the dawning realization that they might now have no choice but to return to the very danger they'd run away from to begin with.

As we walked through the shelter, a woman approached us cautiously. She broke into tears and told us that a few nights earlier she'd woken up to see a man from the shelter trying to sexually assault her underage daughter. Could we help, she asked? We passed on her story to one of the administrative staff at the shelter.

At night, people gathered in a circle to sing hymns, the glittering lights of Juarez in the distance.

The Mexican government has been providing assistance to asylum-seekers who've grown exhausted with the long wait times and difficult conditions, helping to arrange travel back to their countries of origin. A staff member showed us a list of people who'd relented and returned home. In just two months, 205 people had made use of the program and left for Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador. 97 of them were minors.

While that shelter was crowded and lacking the barest level of privacy, it did have security protocols set up to protect people living there. There were heavy gates surrounding the facility and guards who checked the names and credentials of every visitor. This was not the case in other shelters we visited.

At one, a small horseshoe of villas surrounding a decrepit playground on the outskirts of Juarez, there was no gate or security guards at all. The risks facing people stuck there were immediately apparent. Juarez is a dangerous city, and criminals there have realized that migrants have relatives who will often pay ransoms if they are kidnapped. An unsecured shelter is a prime target.

We were there to interview a woman who said she'd been kidnapped near the border by Mexican police officers. She played messages for us that the kidnappers had sent from her phone to her relatives back home. And she told us that not long ago a truck filled with masked men had driven into the shelter and slowly circled the courtyard. Since then she hadn't left her corner of the shelter very often.

As she was telling us her story, we heard crying outside. A legal aid worker who'd brought us to the shelter said that a family living next door had just received word from their son that he'd been kidnapped that day. The boy had been picked up near the shelter and was now texting his mother the ransom demands of his assailants. Our escort offered to take her to a new shelter but she declined, saying she feared that it might seem like she was abandoning her son.

In the wake of a kidnapping the victim's family may be placed under observation by the culprits, and we were told that the presence of journalists with cameras could further endanger the young man. So we quickly left.

In just a brief visit, we'd heard one detailed story of a kidnapping-for-ransom and witnessed another family living through that trauma in real time. The experience underscored the insecurity and fear that tens of thousands of asylum-seekers are being subjected to across the U.S. border right now.

Supporters of the new, punitive asylum processes say that most of the people seeking shelter at our southern border are liars who are after better work opportunities in the U.S. That simply did not gel with much of what we heard. One man said he'd been a municipal employee back home. He liked Honduras, and he hadn't wanted to leave. But a street gang had threatened to murder him and his son if the young boy didn't start selling drugs for them, so he felt they had no choice but to flee.

Another young woman from Nicaragua showed us pictures of the street demonstrations she'd participated in against President Daniel Ortega's government. One of her friends who she'd marched with was killed and others were arrested, so she fled north. Only 19, she looked like a high-school student, speaking in a soft voice with her shoulders drooping as she recounted her separation from her sister at the border.

I have covered challenging stories across the world. For both Guillermo and I, this was a particularly difficult trip. I will not soon forget the eyes of the people we spoke with, at once tired and hopeful, nor their stories of determination, horror, and resilience. The shame I felt as an American while interviewing them was profound. Our country is turning its back on vulnerable people who need our help, right at our doorstop. We have to do better.

The danger they face will not soon come to an end, either. ACLU lawyers have filed suit against every anti-asylum policy the Trump Administration has tried to implement, but the courts have allowed several policies to go forward for now while the litigation against them continues.

The attack on vulnerable people seeking asylum at our border is a political crisis, and we have to start approaching it as the matter of life-and-death that it is. We need our elected representatives - including Democrats vying for the nomination - to take a clear stand and explain what they'll do to roll back these abusive policies as soon as possible.

At stake is our identity as a country. The people asking us for help at our border are no less human than we are, and we have the capacity to help them. How will we respond to their suffering? Will we allow the most hateful and uncaring among us to write our history, or will we fight back and demand better? There are tens of thousands of eyes cast towards us at the border right now waiting for our answer.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Two weeks ago, I traveled to northern Mexico along with Mexican photographer Guillermo Arias to meet with asylum-seekers who've been trapped at the southern U.S. border by Trump Administration policies. Neither of us was prepared for what we saw there.

We visited two cities - Ciudad Juarez and Matamoros--to track down people who had been placed into the deceptively misnamed "Migrant Protection Protocols" that have slammed America's door shut to people fleeing persecution and violence in their home countries. Before we arrived, we wondered whether the stories we'd read of kidnappings, assaults, and despair were as widespread as they sounded. It didn't take long for us to get our answer.

There is--right now, at this very moment--a humanitarian crisis unfolding at our southern border. And we are not paying enough attention to it.

First, a little context. The Trump Administration has been waging an all-out war on the U.S.'s asylum system, which for more than 50 years has provided shelter for people who need protection. To accomplish this reversal of tradition, they've put into place a series of policies that have made it nearly impossible for people to quickly and safely claim asylum at the southern border. Chief among them is the forced return to Mexico program, which has trapped tens of thousands of people in dangerous cartel-controlled cities in northern Mexico while they wait for distant court dates inside the U.S.

The circumstances these vulnerable people are facing in the meantime are dire. We saw them first-hand.

Everywhere we went, people told us stories of being kidnapped or extorted while stuck in Mexico. Many were sleeping in tent encampments on the streets while safety across the border was literally within sight, but legally out of reach. Some were packed into shelters set up by the Mexican government, sleeping shoulder-to-shoulder on thin mattresses on the floor of converted warehouses. Others were living in privately-run shelters with no security protocols to prevent intruders from intimidating or preying on them.

Matamoros is a small city right across the Rio Grande from Brownsville, Texas, just along the coast of the Gulf of Mexico. It's in the Mexican state of Tamaulipas, where corruption and cartel-related violence is so bad that the U.S. state department has given it the same travel advisory as Afghanistan and Somalia. It's also become home to thousands of people who've fled Central America, South America, the Caribbean, Africa, and other parts of Mexico searching for safety.

Previously, they would have been processed through the asylum system and then either detained or released inside the U.S. while their claims were evaluated by an immigration judge. But now, they're given a sheet of paper that tells them to come back to the border months later for their first hearing. In the meantime, they're stuck, with nowhere to go and most often nobody to help them. Next to the Matamoros-Brownsville bridge, a tent camp has sprung up on a patch of pavement and dirt that around 2,000 asylum-seekers call home. The camp is growing every day.

The night before we visited, a storm system had swept through Texas, flooding the inside of the low-quality tents people were living in with rain. There was mud everywhere, and it was cold. Few people had the clothing to cope with the chilly temperatures, and the first few people we talked to were shivering, their teeth chattering as they spoke. Everywhere we looked, there were very young children sitting on curbs or hanging onto their parents.

One young man told us that in a tent nearby there was a Honduran woman with a newborn baby, so we stopped in to visit them. She'd delivered just five days earlier. Only 21 years old herself, she'd been living in the tent with her four-year-old daughter since being sent back to Matamoros by Customs and Border Protection agents. She said that when she'd first told CBP officers that she was pregnant, they suggested she get an abortion before telling her to come back for a court date over a month in the future.

The tiny child was bundled into blankets in the small tent where it was spending its first days of life. Her mother coughed when she spoke, visibly exhausted. She said that she'd fled an abusive spouse and was too afraid to return to him. Later, one of the few health responders who visits the camp regularly told me that she was fearful about whether the child would survive conditions at the camp, which she said reminded her of refugee camps she'd worked at in Bangladesh.

"If there's a cholera outbreak here, half of them could die," she said.

Further up the hill next to the camp, along a wooded grove, lies the Rio Grande. There are a few makeshift showers near the camp, but they aren't nearly enough for the entire camp to bathe, so many choose to wash and do their laundry at the bank of the river. The river is rife with pollution, and people living in the camp have developed rashes and other skin problems from bathing in it. Next to a small, muddy clearing, a series of white crosses stood in remembrance of the children who've died by drowning in the river in recent months.

A few nights before we visited the camp in Matamoros, some of its frustrated residents had staged a protest against conditions in the camp and the policies that have trapped them there, shutting down the bridge for 15 hours. "They keep telling us we have to wait longer and longer," one told Buzzfeed News. "When will it end?"

Walking among the tents and meeting their gracious and welcoming occupants, I felt the weight of my country's responsibility for their suffering. The insecurity, desperation, and discomfort of the people we were speaking with isn't a corollary effect of the policy, it's the core intent. The "Migrant Protection Protocols" were designed to make it so uncomfortable and dangerous for people who are seeking asylum that they will simply give up, exhausted and defeated, and return back to the dangerous situations they fled.

Many have, indeed, already done so.

Further along the border, in Ciudad Juarez, we visited a network of shelters that have been set up in recent months to cope with the roughly 17,000 asylum-seekers who've been returned there since mid-April. On one side of the spectrum was the newly-opened federal shelter, supervised by the Mexican government, which was housing over 500 people the week we were there. A converted warehouse with no individual rooms, people were sleeping on rows and rows of small mattresses lined up against the walls and across the middle of the large hall. Its inhabitants were there waiting for court hearings as far out as January of next year.

We met with Venezuelans who'd fled the political crisis in their country and El Salvadorans who spoke of witnessing family members gunned down in front of them. People told us they'd been dropped off on darkened streets in Juarez by Customs and Border Protection with no idea where to go or what to do. One parent told us she'd had to wrestle with a man who tried to abduct her daughter in front of her. Some spoke of the dawning realization that they might now have no choice but to return to the very danger they'd run away from to begin with.

As we walked through the shelter, a woman approached us cautiously. She broke into tears and told us that a few nights earlier she'd woken up to see a man from the shelter trying to sexually assault her underage daughter. Could we help, she asked? We passed on her story to one of the administrative staff at the shelter.

At night, people gathered in a circle to sing hymns, the glittering lights of Juarez in the distance.

The Mexican government has been providing assistance to asylum-seekers who've grown exhausted with the long wait times and difficult conditions, helping to arrange travel back to their countries of origin. A staff member showed us a list of people who'd relented and returned home. In just two months, 205 people had made use of the program and left for Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador. 97 of them were minors.

While that shelter was crowded and lacking the barest level of privacy, it did have security protocols set up to protect people living there. There were heavy gates surrounding the facility and guards who checked the names and credentials of every visitor. This was not the case in other shelters we visited.

At one, a small horseshoe of villas surrounding a decrepit playground on the outskirts of Juarez, there was no gate or security guards at all. The risks facing people stuck there were immediately apparent. Juarez is a dangerous city, and criminals there have realized that migrants have relatives who will often pay ransoms if they are kidnapped. An unsecured shelter is a prime target.

We were there to interview a woman who said she'd been kidnapped near the border by Mexican police officers. She played messages for us that the kidnappers had sent from her phone to her relatives back home. And she told us that not long ago a truck filled with masked men had driven into the shelter and slowly circled the courtyard. Since then she hadn't left her corner of the shelter very often.

As she was telling us her story, we heard crying outside. A legal aid worker who'd brought us to the shelter said that a family living next door had just received word from their son that he'd been kidnapped that day. The boy had been picked up near the shelter and was now texting his mother the ransom demands of his assailants. Our escort offered to take her to a new shelter but she declined, saying she feared that it might seem like she was abandoning her son.

In the wake of a kidnapping the victim's family may be placed under observation by the culprits, and we were told that the presence of journalists with cameras could further endanger the young man. So we quickly left.

In just a brief visit, we'd heard one detailed story of a kidnapping-for-ransom and witnessed another family living through that trauma in real time. The experience underscored the insecurity and fear that tens of thousands of asylum-seekers are being subjected to across the U.S. border right now.

Supporters of the new, punitive asylum processes say that most of the people seeking shelter at our southern border are liars who are after better work opportunities in the U.S. That simply did not gel with much of what we heard. One man said he'd been a municipal employee back home. He liked Honduras, and he hadn't wanted to leave. But a street gang had threatened to murder him and his son if the young boy didn't start selling drugs for them, so he felt they had no choice but to flee.

Another young woman from Nicaragua showed us pictures of the street demonstrations she'd participated in against President Daniel Ortega's government. One of her friends who she'd marched with was killed and others were arrested, so she fled north. Only 19, she looked like a high-school student, speaking in a soft voice with her shoulders drooping as she recounted her separation from her sister at the border.

I have covered challenging stories across the world. For both Guillermo and I, this was a particularly difficult trip. I will not soon forget the eyes of the people we spoke with, at once tired and hopeful, nor their stories of determination, horror, and resilience. The shame I felt as an American while interviewing them was profound. Our country is turning its back on vulnerable people who need our help, right at our doorstop. We have to do better.

The danger they face will not soon come to an end, either. ACLU lawyers have filed suit against every anti-asylum policy the Trump Administration has tried to implement, but the courts have allowed several policies to go forward for now while the litigation against them continues.

The attack on vulnerable people seeking asylum at our border is a political crisis, and we have to start approaching it as the matter of life-and-death that it is. We need our elected representatives - including Democrats vying for the nomination - to take a clear stand and explain what they'll do to roll back these abusive policies as soon as possible.

At stake is our identity as a country. The people asking us for help at our border are no less human than we are, and we have the capacity to help them. How will we respond to their suffering? Will we allow the most hateful and uncaring among us to write our history, or will we fight back and demand better? There are tens of thousands of eyes cast towards us at the border right now waiting for our answer.

Two weeks ago, I traveled to northern Mexico along with Mexican photographer Guillermo Arias to meet with asylum-seekers who've been trapped at the southern U.S. border by Trump Administration policies. Neither of us was prepared for what we saw there.

We visited two cities - Ciudad Juarez and Matamoros--to track down people who had been placed into the deceptively misnamed "Migrant Protection Protocols" that have slammed America's door shut to people fleeing persecution and violence in their home countries. Before we arrived, we wondered whether the stories we'd read of kidnappings, assaults, and despair were as widespread as they sounded. It didn't take long for us to get our answer.

There is--right now, at this very moment--a humanitarian crisis unfolding at our southern border. And we are not paying enough attention to it.

First, a little context. The Trump Administration has been waging an all-out war on the U.S.'s asylum system, which for more than 50 years has provided shelter for people who need protection. To accomplish this reversal of tradition, they've put into place a series of policies that have made it nearly impossible for people to quickly and safely claim asylum at the southern border. Chief among them is the forced return to Mexico program, which has trapped tens of thousands of people in dangerous cartel-controlled cities in northern Mexico while they wait for distant court dates inside the U.S.

The circumstances these vulnerable people are facing in the meantime are dire. We saw them first-hand.

Everywhere we went, people told us stories of being kidnapped or extorted while stuck in Mexico. Many were sleeping in tent encampments on the streets while safety across the border was literally within sight, but legally out of reach. Some were packed into shelters set up by the Mexican government, sleeping shoulder-to-shoulder on thin mattresses on the floor of converted warehouses. Others were living in privately-run shelters with no security protocols to prevent intruders from intimidating or preying on them.

Matamoros is a small city right across the Rio Grande from Brownsville, Texas, just along the coast of the Gulf of Mexico. It's in the Mexican state of Tamaulipas, where corruption and cartel-related violence is so bad that the U.S. state department has given it the same travel advisory as Afghanistan and Somalia. It's also become home to thousands of people who've fled Central America, South America, the Caribbean, Africa, and other parts of Mexico searching for safety.

Previously, they would have been processed through the asylum system and then either detained or released inside the U.S. while their claims were evaluated by an immigration judge. But now, they're given a sheet of paper that tells them to come back to the border months later for their first hearing. In the meantime, they're stuck, with nowhere to go and most often nobody to help them. Next to the Matamoros-Brownsville bridge, a tent camp has sprung up on a patch of pavement and dirt that around 2,000 asylum-seekers call home. The camp is growing every day.

The night before we visited, a storm system had swept through Texas, flooding the inside of the low-quality tents people were living in with rain. There was mud everywhere, and it was cold. Few people had the clothing to cope with the chilly temperatures, and the first few people we talked to were shivering, their teeth chattering as they spoke. Everywhere we looked, there were very young children sitting on curbs or hanging onto their parents.

One young man told us that in a tent nearby there was a Honduran woman with a newborn baby, so we stopped in to visit them. She'd delivered just five days earlier. Only 21 years old herself, she'd been living in the tent with her four-year-old daughter since being sent back to Matamoros by Customs and Border Protection agents. She said that when she'd first told CBP officers that she was pregnant, they suggested she get an abortion before telling her to come back for a court date over a month in the future.

The tiny child was bundled into blankets in the small tent where it was spending its first days of life. Her mother coughed when she spoke, visibly exhausted. She said that she'd fled an abusive spouse and was too afraid to return to him. Later, one of the few health responders who visits the camp regularly told me that she was fearful about whether the child would survive conditions at the camp, which she said reminded her of refugee camps she'd worked at in Bangladesh.

"If there's a cholera outbreak here, half of them could die," she said.

Further up the hill next to the camp, along a wooded grove, lies the Rio Grande. There are a few makeshift showers near the camp, but they aren't nearly enough for the entire camp to bathe, so many choose to wash and do their laundry at the bank of the river. The river is rife with pollution, and people living in the camp have developed rashes and other skin problems from bathing in it. Next to a small, muddy clearing, a series of white crosses stood in remembrance of the children who've died by drowning in the river in recent months.

A few nights before we visited the camp in Matamoros, some of its frustrated residents had staged a protest against conditions in the camp and the policies that have trapped them there, shutting down the bridge for 15 hours. "They keep telling us we have to wait longer and longer," one told Buzzfeed News. "When will it end?"

Walking among the tents and meeting their gracious and welcoming occupants, I felt the weight of my country's responsibility for their suffering. The insecurity, desperation, and discomfort of the people we were speaking with isn't a corollary effect of the policy, it's the core intent. The "Migrant Protection Protocols" were designed to make it so uncomfortable and dangerous for people who are seeking asylum that they will simply give up, exhausted and defeated, and return back to the dangerous situations they fled.

Many have, indeed, already done so.

Further along the border, in Ciudad Juarez, we visited a network of shelters that have been set up in recent months to cope with the roughly 17,000 asylum-seekers who've been returned there since mid-April. On one side of the spectrum was the newly-opened federal shelter, supervised by the Mexican government, which was housing over 500 people the week we were there. A converted warehouse with no individual rooms, people were sleeping on rows and rows of small mattresses lined up against the walls and across the middle of the large hall. Its inhabitants were there waiting for court hearings as far out as January of next year.

We met with Venezuelans who'd fled the political crisis in their country and El Salvadorans who spoke of witnessing family members gunned down in front of them. People told us they'd been dropped off on darkened streets in Juarez by Customs and Border Protection with no idea where to go or what to do. One parent told us she'd had to wrestle with a man who tried to abduct her daughter in front of her. Some spoke of the dawning realization that they might now have no choice but to return to the very danger they'd run away from to begin with.

As we walked through the shelter, a woman approached us cautiously. She broke into tears and told us that a few nights earlier she'd woken up to see a man from the shelter trying to sexually assault her underage daughter. Could we help, she asked? We passed on her story to one of the administrative staff at the shelter.

At night, people gathered in a circle to sing hymns, the glittering lights of Juarez in the distance.

The Mexican government has been providing assistance to asylum-seekers who've grown exhausted with the long wait times and difficult conditions, helping to arrange travel back to their countries of origin. A staff member showed us a list of people who'd relented and returned home. In just two months, 205 people had made use of the program and left for Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador. 97 of them were minors.

While that shelter was crowded and lacking the barest level of privacy, it did have security protocols set up to protect people living there. There were heavy gates surrounding the facility and guards who checked the names and credentials of every visitor. This was not the case in other shelters we visited.

At one, a small horseshoe of villas surrounding a decrepit playground on the outskirts of Juarez, there was no gate or security guards at all. The risks facing people stuck there were immediately apparent. Juarez is a dangerous city, and criminals there have realized that migrants have relatives who will often pay ransoms if they are kidnapped. An unsecured shelter is a prime target.

We were there to interview a woman who said she'd been kidnapped near the border by Mexican police officers. She played messages for us that the kidnappers had sent from her phone to her relatives back home. And she told us that not long ago a truck filled with masked men had driven into the shelter and slowly circled the courtyard. Since then she hadn't left her corner of the shelter very often.

As she was telling us her story, we heard crying outside. A legal aid worker who'd brought us to the shelter said that a family living next door had just received word from their son that he'd been kidnapped that day. The boy had been picked up near the shelter and was now texting his mother the ransom demands of his assailants. Our escort offered to take her to a new shelter but she declined, saying she feared that it might seem like she was abandoning her son.

In the wake of a kidnapping the victim's family may be placed under observation by the culprits, and we were told that the presence of journalists with cameras could further endanger the young man. So we quickly left.

In just a brief visit, we'd heard one detailed story of a kidnapping-for-ransom and witnessed another family living through that trauma in real time. The experience underscored the insecurity and fear that tens of thousands of asylum-seekers are being subjected to across the U.S. border right now.

Supporters of the new, punitive asylum processes say that most of the people seeking shelter at our southern border are liars who are after better work opportunities in the U.S. That simply did not gel with much of what we heard. One man said he'd been a municipal employee back home. He liked Honduras, and he hadn't wanted to leave. But a street gang had threatened to murder him and his son if the young boy didn't start selling drugs for them, so he felt they had no choice but to flee.

Another young woman from Nicaragua showed us pictures of the street demonstrations she'd participated in against President Daniel Ortega's government. One of her friends who she'd marched with was killed and others were arrested, so she fled north. Only 19, she looked like a high-school student, speaking in a soft voice with her shoulders drooping as she recounted her separation from her sister at the border.

I have covered challenging stories across the world. For both Guillermo and I, this was a particularly difficult trip. I will not soon forget the eyes of the people we spoke with, at once tired and hopeful, nor their stories of determination, horror, and resilience. The shame I felt as an American while interviewing them was profound. Our country is turning its back on vulnerable people who need our help, right at our doorstop. We have to do better.

The danger they face will not soon come to an end, either. ACLU lawyers have filed suit against every anti-asylum policy the Trump Administration has tried to implement, but the courts have allowed several policies to go forward for now while the litigation against them continues.

The attack on vulnerable people seeking asylum at our border is a political crisis, and we have to start approaching it as the matter of life-and-death that it is. We need our elected representatives - including Democrats vying for the nomination - to take a clear stand and explain what they'll do to roll back these abusive policies as soon as possible.

At stake is our identity as a country. The people asking us for help at our border are no less human than we are, and we have the capacity to help them. How will we respond to their suffering? Will we allow the most hateful and uncaring among us to write our history, or will we fight back and demand better? There are tens of thousands of eyes cast towards us at the border right now waiting for our answer.