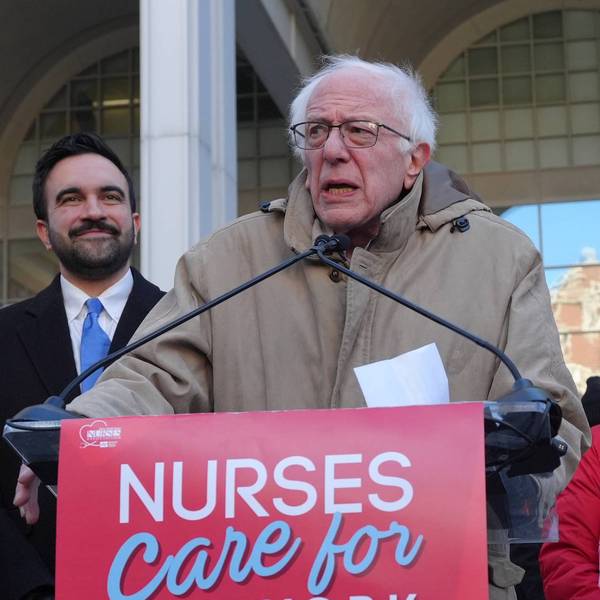

"Last week, Bernie Sanders released a plan to revitalize school integration efforts," explains Cooper. "It's both an excellent plan and brings attention to a vitally important racial justice issue." (Photo: BernieSanders.com)

Bernie Sanders Is Bringing Back the Most Underrated Education Policy

School integration has been outside the main political discussion for a long time, and it's long since time we started talking about it again.

Over the past two decades, education reform has been a major topic of debate and policymaking, from President Bush's No Child Left Behind bill to President Obama's Race to the Top initiative. Reforms have generally followed the pattern of adapting mechanisms from the for-profit business world to "fix" supposedly broken aspects of the public education system: weakening teacher unions, replacing public schools with privately-run charters, tying teacher pay to test score results, and so on.

Yet there is one idea that was once a major focus of reform efforts, but has been set aside for years: racial desegregation.

That is, until now. Last week, Bernie Sanders released a plan to revitalize school integration efforts. It's both an excellent plan and brings attention to a vitally important racial justice issue.

Historical context is important here. For a couple decades after the civil rights legislation of the 1960s, the federal government put real effort into forcing school districts to integrate their populations. The main objective was to equalize educational opportunity, particularly in the South. Stuffing black populations into crummy, under-resourced institutions was one of the major mechanisms of the Jim Crow apartheid system -- but if white and black children went to the same schools, then they should receive education of a similar quality (or at least a lot closer than before).

Because cities across the nation were (and remain) extremely segregated, and whites violently resisted any attempt to integrate actual neighborhoods, the only realistic option was using transportation to achieve a decent demographic mix. But this led to an enormous white backlash across the country.

It turned out northern schools were just as segregated as southern ones, if not worse, and northern whites were not any keener on integration than southern ones -- indeed, an integration plan in Boston sparked violent riots. Centrist triangulators like then-Senator Joe Biden (D-Del.), seized on the issue, teaming up with southern segregationists to beat back integration efforts. (In 1977 Biden wrote to Dixiecrat Senator James Eastland of Missippi: "I want you to know that I very much appreciate your help during this week's committee meeting in attempting to bring my anti-busing legislation to a vote.")

It's key to understand that the rhetoric of the anti-integration backlash was total nonsense. Biden (along with infamous racists like George Wallace and Louise Day Hicks) called integration "forced busing," portraying it as a simple defense of the traditional neighborhood school.

In reality, as historian Matt Delmont writes in Why Busing Failed, busing has always been common in schools, and had been used as a key tool of segregation itself prior to the Civil Rights Movement. Indeed, the very plaintiff in Brown vs. Board of Education was a girl who was bused 20 miles to a black school when she lived just four blocks from a white one. Integration sometimes meant children being transported to a far-off school, but not always. Conversely, long-distance busing is still common today -- nobody complains when their kid gets a slot in a high-status, distant magnet school. What whites really objected to (then and now) was their children attending school with blacks. It's a simple as that.

The educational benefits of integration are large. One study found that "for blacks, school desegregation significantly increased both educational and occupational attainments, college quality and adult earnings, reduced the probability of incarceration, and improved adult health status; desegregation had no effects on whites across each of these outcomes."

Conversely, as this Tampa Bay Times investigation shows, when one Florida county got out from under a federal desegration order in 2007, they immediately re-segregated their schools -- warehousing most of their poor black population in five schools, and starving them of resources. They quickly plunged from average or above-average in quality to some of the worst in the entire state, with 95 percent of students failing reading or math.

So what would Sanders do? He would end the prohibition on funding desegregation transport (a relic from that 1970's backlash), provide several pots of money to encourage schools to desegregate, triple funding support for the poorest schools, expand funding for minority teacher education, ramp up desegregation orders, and provide more money for school construction and maintenance, (as well as several other policies not directly related to desegregation). It's an excellent start, to say the least.

A Biden spokesman, by contrast, told CNN that Biden stands by his segregationist record.

Other 2020 Democrats have so far largely avoided the topic. Only Julian Castro has offered a plan to combat school segregation, but only through integrating neighborhoods, which while a worthy goal (ideally, both should be done) would be both more difficult and take much longer.

Now, integration is not a panacea; a disproportionate number of African-American children still come from impoverished families or face other problems rooted in systemic racism. And the biggest overall problem with American education is certainly America's hideous income inequality, as household income is very closely correlated with educational achievement. But integration does prevent them from being stuffed into essentially fake schools where rich white elites can simply let them drown -- and it doesn't harm white children either.

It's also true that the federal government's power over the school system is not that great, as most power is still exercised locally. But a committed president could still achieve a lot, and more still with the support of Congress. School integration has been outside the main political discussion for a long time, and it's long since time we started talking about it again.

Bernie Sanders deserves enormous credit for bringing it back on the national radar and offering a meaningful plan to address it.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Over the past two decades, education reform has been a major topic of debate and policymaking, from President Bush's No Child Left Behind bill to President Obama's Race to the Top initiative. Reforms have generally followed the pattern of adapting mechanisms from the for-profit business world to "fix" supposedly broken aspects of the public education system: weakening teacher unions, replacing public schools with privately-run charters, tying teacher pay to test score results, and so on.

Yet there is one idea that was once a major focus of reform efforts, but has been set aside for years: racial desegregation.

That is, until now. Last week, Bernie Sanders released a plan to revitalize school integration efforts. It's both an excellent plan and brings attention to a vitally important racial justice issue.

Historical context is important here. For a couple decades after the civil rights legislation of the 1960s, the federal government put real effort into forcing school districts to integrate their populations. The main objective was to equalize educational opportunity, particularly in the South. Stuffing black populations into crummy, under-resourced institutions was one of the major mechanisms of the Jim Crow apartheid system -- but if white and black children went to the same schools, then they should receive education of a similar quality (or at least a lot closer than before).

Because cities across the nation were (and remain) extremely segregated, and whites violently resisted any attempt to integrate actual neighborhoods, the only realistic option was using transportation to achieve a decent demographic mix. But this led to an enormous white backlash across the country.

It turned out northern schools were just as segregated as southern ones, if not worse, and northern whites were not any keener on integration than southern ones -- indeed, an integration plan in Boston sparked violent riots. Centrist triangulators like then-Senator Joe Biden (D-Del.), seized on the issue, teaming up with southern segregationists to beat back integration efforts. (In 1977 Biden wrote to Dixiecrat Senator James Eastland of Missippi: "I want you to know that I very much appreciate your help during this week's committee meeting in attempting to bring my anti-busing legislation to a vote.")

It's key to understand that the rhetoric of the anti-integration backlash was total nonsense. Biden (along with infamous racists like George Wallace and Louise Day Hicks) called integration "forced busing," portraying it as a simple defense of the traditional neighborhood school.

In reality, as historian Matt Delmont writes in Why Busing Failed, busing has always been common in schools, and had been used as a key tool of segregation itself prior to the Civil Rights Movement. Indeed, the very plaintiff in Brown vs. Board of Education was a girl who was bused 20 miles to a black school when she lived just four blocks from a white one. Integration sometimes meant children being transported to a far-off school, but not always. Conversely, long-distance busing is still common today -- nobody complains when their kid gets a slot in a high-status, distant magnet school. What whites really objected to (then and now) was their children attending school with blacks. It's a simple as that.

The educational benefits of integration are large. One study found that "for blacks, school desegregation significantly increased both educational and occupational attainments, college quality and adult earnings, reduced the probability of incarceration, and improved adult health status; desegregation had no effects on whites across each of these outcomes."

Conversely, as this Tampa Bay Times investigation shows, when one Florida county got out from under a federal desegration order in 2007, they immediately re-segregated their schools -- warehousing most of their poor black population in five schools, and starving them of resources. They quickly plunged from average or above-average in quality to some of the worst in the entire state, with 95 percent of students failing reading or math.

So what would Sanders do? He would end the prohibition on funding desegregation transport (a relic from that 1970's backlash), provide several pots of money to encourage schools to desegregate, triple funding support for the poorest schools, expand funding for minority teacher education, ramp up desegregation orders, and provide more money for school construction and maintenance, (as well as several other policies not directly related to desegregation). It's an excellent start, to say the least.

A Biden spokesman, by contrast, told CNN that Biden stands by his segregationist record.

Other 2020 Democrats have so far largely avoided the topic. Only Julian Castro has offered a plan to combat school segregation, but only through integrating neighborhoods, which while a worthy goal (ideally, both should be done) would be both more difficult and take much longer.

Now, integration is not a panacea; a disproportionate number of African-American children still come from impoverished families or face other problems rooted in systemic racism. And the biggest overall problem with American education is certainly America's hideous income inequality, as household income is very closely correlated with educational achievement. But integration does prevent them from being stuffed into essentially fake schools where rich white elites can simply let them drown -- and it doesn't harm white children either.

It's also true that the federal government's power over the school system is not that great, as most power is still exercised locally. But a committed president could still achieve a lot, and more still with the support of Congress. School integration has been outside the main political discussion for a long time, and it's long since time we started talking about it again.

Bernie Sanders deserves enormous credit for bringing it back on the national radar and offering a meaningful plan to address it.

Over the past two decades, education reform has been a major topic of debate and policymaking, from President Bush's No Child Left Behind bill to President Obama's Race to the Top initiative. Reforms have generally followed the pattern of adapting mechanisms from the for-profit business world to "fix" supposedly broken aspects of the public education system: weakening teacher unions, replacing public schools with privately-run charters, tying teacher pay to test score results, and so on.

Yet there is one idea that was once a major focus of reform efforts, but has been set aside for years: racial desegregation.

That is, until now. Last week, Bernie Sanders released a plan to revitalize school integration efforts. It's both an excellent plan and brings attention to a vitally important racial justice issue.

Historical context is important here. For a couple decades after the civil rights legislation of the 1960s, the federal government put real effort into forcing school districts to integrate their populations. The main objective was to equalize educational opportunity, particularly in the South. Stuffing black populations into crummy, under-resourced institutions was one of the major mechanisms of the Jim Crow apartheid system -- but if white and black children went to the same schools, then they should receive education of a similar quality (or at least a lot closer than before).

Because cities across the nation were (and remain) extremely segregated, and whites violently resisted any attempt to integrate actual neighborhoods, the only realistic option was using transportation to achieve a decent demographic mix. But this led to an enormous white backlash across the country.

It turned out northern schools were just as segregated as southern ones, if not worse, and northern whites were not any keener on integration than southern ones -- indeed, an integration plan in Boston sparked violent riots. Centrist triangulators like then-Senator Joe Biden (D-Del.), seized on the issue, teaming up with southern segregationists to beat back integration efforts. (In 1977 Biden wrote to Dixiecrat Senator James Eastland of Missippi: "I want you to know that I very much appreciate your help during this week's committee meeting in attempting to bring my anti-busing legislation to a vote.")

It's key to understand that the rhetoric of the anti-integration backlash was total nonsense. Biden (along with infamous racists like George Wallace and Louise Day Hicks) called integration "forced busing," portraying it as a simple defense of the traditional neighborhood school.

In reality, as historian Matt Delmont writes in Why Busing Failed, busing has always been common in schools, and had been used as a key tool of segregation itself prior to the Civil Rights Movement. Indeed, the very plaintiff in Brown vs. Board of Education was a girl who was bused 20 miles to a black school when she lived just four blocks from a white one. Integration sometimes meant children being transported to a far-off school, but not always. Conversely, long-distance busing is still common today -- nobody complains when their kid gets a slot in a high-status, distant magnet school. What whites really objected to (then and now) was their children attending school with blacks. It's a simple as that.

The educational benefits of integration are large. One study found that "for blacks, school desegregation significantly increased both educational and occupational attainments, college quality and adult earnings, reduced the probability of incarceration, and improved adult health status; desegregation had no effects on whites across each of these outcomes."

Conversely, as this Tampa Bay Times investigation shows, when one Florida county got out from under a federal desegration order in 2007, they immediately re-segregated their schools -- warehousing most of their poor black population in five schools, and starving them of resources. They quickly plunged from average or above-average in quality to some of the worst in the entire state, with 95 percent of students failing reading or math.

So what would Sanders do? He would end the prohibition on funding desegregation transport (a relic from that 1970's backlash), provide several pots of money to encourage schools to desegregate, triple funding support for the poorest schools, expand funding for minority teacher education, ramp up desegregation orders, and provide more money for school construction and maintenance, (as well as several other policies not directly related to desegregation). It's an excellent start, to say the least.

A Biden spokesman, by contrast, told CNN that Biden stands by his segregationist record.

Other 2020 Democrats have so far largely avoided the topic. Only Julian Castro has offered a plan to combat school segregation, but only through integrating neighborhoods, which while a worthy goal (ideally, both should be done) would be both more difficult and take much longer.

Now, integration is not a panacea; a disproportionate number of African-American children still come from impoverished families or face other problems rooted in systemic racism. And the biggest overall problem with American education is certainly America's hideous income inequality, as household income is very closely correlated with educational achievement. But integration does prevent them from being stuffed into essentially fake schools where rich white elites can simply let them drown -- and it doesn't harm white children either.

It's also true that the federal government's power over the school system is not that great, as most power is still exercised locally. But a committed president could still achieve a lot, and more still with the support of Congress. School integration has been outside the main political discussion for a long time, and it's long since time we started talking about it again.

Bernie Sanders deserves enormous credit for bringing it back on the national radar and offering a meaningful plan to address it.