SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

Call this elision what it is: war propaganda. (Photo: Screenshot)

The US media chorus supporting a US overthrow of the Venezuelan government has for years pointed to the country's economic crisis as a justification for regime change, while whitewashing the ways in which the US has strangled the Venezuelan economy (FAIR.org, 3/22/18).

Sister Eugenia Russian, president of Fundalatin, a Venezuelan human rights NGO that was established in 1978 and has special consultative status at the UN, told the Independent (1/26/19):

In contact with the popular communities, we consider that one of the fundamental causes of the economic crisis in the country is the effect [of] the unilateral coercive sanctions that are applied in the economy, especially by the government of the United States.

While internal errors also contributed to the nation's problems, Russian said it's likely that few countries in the world have ever suffered an "economic siege" like the one Venezuelans are living under.

While the New York Times and the Washington Post have lately professed profound (and definitely 100 percent sincere) concern for the welfare of Venezuelans, neither publication has ever referred to Fundalatin.

Alfred de Zayas, the first UN special rapporteur to visit Venezuela in 21 years, told the Independent (1/26/19) that US, Canadian and European Union "economic warfare" has killed Venezuelans, noting that the sanctions fall most heavily on the poorest people and demonstrably cause death through food and medicine shortages, lead to violations of human rights and are aimed at coercing economic change in a "sister democracy."

De Zayas' UN report noted that sanctions "hind[er] the imports necessary to produce generic medicines and seeds to increase agricultural production." De Zayas also cited Venezuelan economist Pasqualina Curcio, who reports that "the most effective strategy to disrupt the Venezuelan economy" has been the manipulation of the exchange rate. The rapporteur went on to suggest that the International Criminal Court investigate economic sanctions against Venezuela as possible crimes against humanity.

Given that de Zayas is the first UN special rapporteur to report on Venezuela in more than two decades, one might expect the media to regard his findings as an important part of the Venezuela narrative, but his name does not appear in a single article ever published in the Post; the Times has mentioned him once, but not in relation to Venezuela.

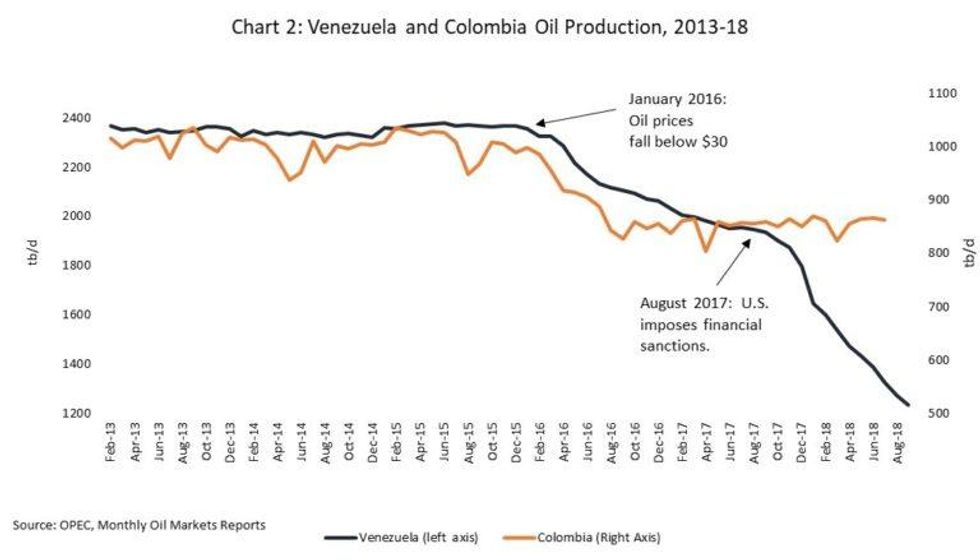

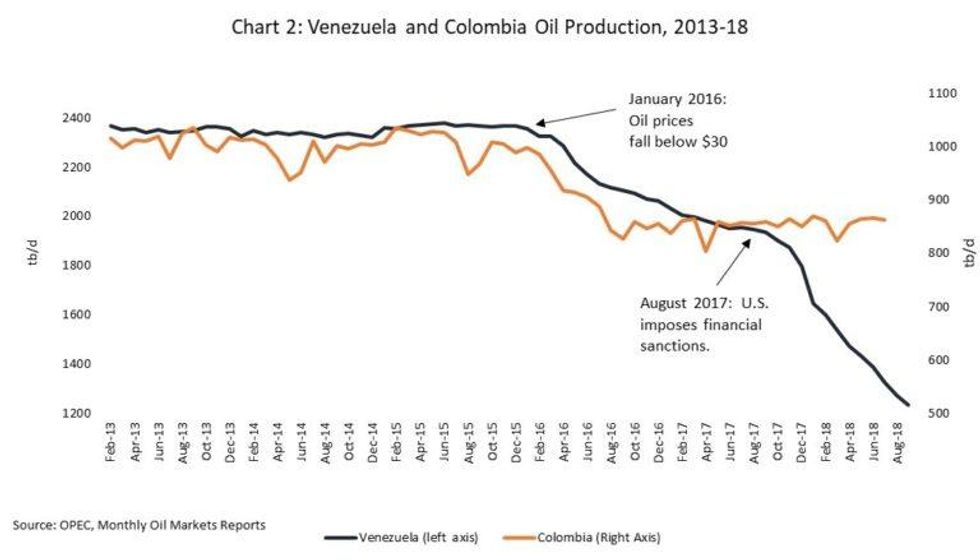

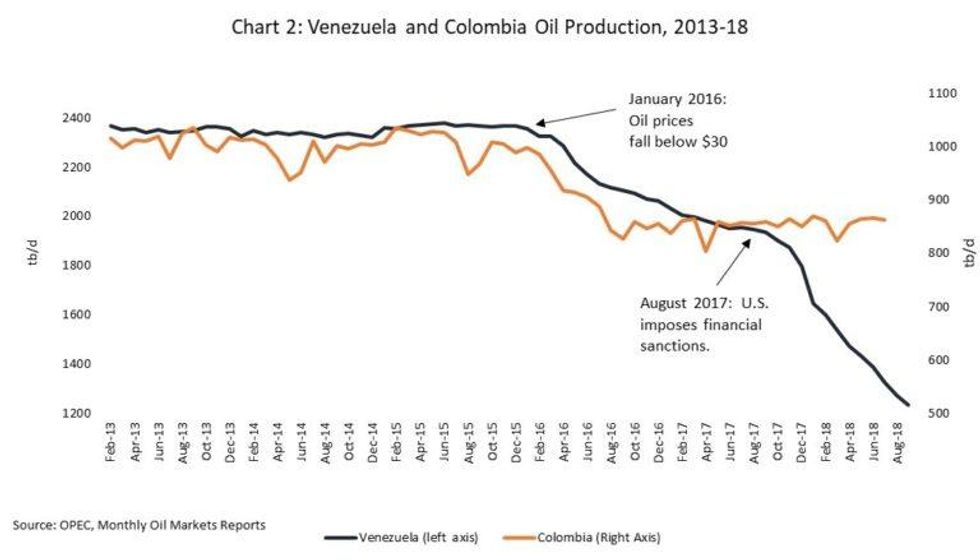

The economist Francisco Rodriguez points out that the sanctions the Trump administration issued in August 2017 prohibited US banks from providing new financing to the Venezuelan government, a key part of the "toxification" of financial dealings with Venezuela. Rodriguez notes that, in August 2017, the US Financial Crimes Enforcement Network warned financial institutions that "all Venezuelan government agencies and bodies...appear vulnerable to public corruption and money laundering," and recommended that some transactions originating from Venezuela be flagged as potentially criminal. Many financial institutions then closed Venezuelan accounts, concerned about the risk of being accused of participating in money laundering.

Rodriguez says that this handcuffed Venezuela's oil industry, the sector most crucial to its economy, with lost access to credit preventing the country from obtaining financial resources that could have been devoted to investment or maintenance. And whereas previously the Venezuelan government would raise production by signing joint venture agreements with foreign partners who would finance investment, Trump's sanctions "effectively put an end to these loans."

Mark Weisbrot (The Nation, 9/7/17) , also an economist, raised a related issue:

If we step back and look at Venezuela from a bird's-eye view, how does a country with 500 billion barrels of oil and hundreds of billions of dollars' worth of minerals in the ground go broke? The only way that can happen is if the country is cut off from the international financial system. Otherwise, Venezuela could sell or even collateralize some of its resources in order to get the necessary dollars. The $7.7 billion in gold held in Central Bank reserves could be quickly collateralized for a loan; in past years, the US Treasury department used its clout to make sure that banks who wanted to finance a swap, such as JPMorgan Chase and Bank of America, did not do so.

Sanctions have kept the Venezuelan government from accessing financing and dealing with its debt while hamstringing its most important industry. Given that US media are writing for a principally US audience, the damage done by Washington and its partners' sanctions should be front and center in their coverage. Exactly the opposite is the case.

Virginia Lopez-Glass of the New York Times (1/25/19) uses 920 words to describe the challenges facing Venezuelans, but "sanctions" isn't one of them, even as she writes about matters to which, as I've shown above, sanctions are directly relevant: "Food and medicine shortages are widespread. Hundreds have died from malnutrition and illnesses that are easily curable with the appropriate treatment."

Weaponizing hunger in Venezuela in this manner is dishonest and misleading. Christina M. Schiavoni, a doctoral researcher at the International Institute of Social Studies in The Hague, and Ana Felicien and Liccia Romero, both of whom are Venezuelan scholars, wrote in Monthly Review (6/1/18) on "overt US aggression toward Venezuela" in the form of

the intensifying economic sanctions imposed by the Obama and Trump administrations, as well as an all-out economic blockade that has made it extremely difficult for the government to make payments on food imports and manage its debt.

Bret Stephens' column in the Times (1/28/19) only mentions the word "sanctions" to complain that the media supposedly isn't blaming "socialism" for the crisis in Venezuela, alleging that

what you're likelier to read is that the crisis is the product of corruption, cronyism, populism, authoritarianism, resource-dependency, US sanctions and trickery, even the residues of capitalism itself.

After dismissing the idea that the sanctions are a key part of the problems in Venezuela, Stephens went on to advocate using them to bring about regime change in the country, writing that the Trump administration

should enhance [Guaido]'s political standing by providing access to funds that can help him establish an alternative government and entice wavering figures in the Maduro camp to switch sides. It can put Venezuela on the list of state sponsors of terrorism.

These "funds" presumably refer the money that the US has seized from Venezuela, and adding the country to list of "state sponsors of terrorism" automatically entails hitting it with further sanctions.

The editorial board of the Washington Post (1/24/19) alleged that Venezuela's government has "subject[ed] the country's 32 million people to a humanitarian catastrophe," without referring to what scholars whose research and writing focuses on Latin America--such as Laura Carlsen, Sujatha Fernandes, Greg Grandin, Francisco Dominguez, Noam Chomsky, Aviva Chomsky, Gabriel Hetland and Venezuelan-born historian Miguel Tinker Salas--describe (Common Dreams, 1/24/19) as sanctions

cut[ting] off the means by which the Venezuelan government could escape from its economic recession, while causing a dramatic falloff in oil production and worsening the economic crisis, and causing many people to die because they can't get access to life-saving medicines.

Later, the editorial said that "a US boycott of Venezuelan oil could endanger ordinary Venezuelans already coping with critical shortages of food, power and medicine," an absurd remark given that the sanctions they are occluding have had precisely these effects.

Henry Olsen in the Post (1/24/19) wrote as if sanctions are a benign tool that can be used to usher in a brighter future for Venezuelans, rather than a key reason that so many of them find themselves in such a grim condition:

Trump has many levers to pull short of military intervention to topple Maduro. He could use US pressure on the global financial system to cut off regime access to international banks, freezing access to any secret accounts that the regime -- and, probably, its highest-ranking leaders -- established offshore. He can, as Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.) has suggested, work with American oil companies that purchase Venezuelan oil to provide the profits from those purchases to accounts controlled by Guaido's National Assembly. He can also pressure China, which has a far more valuable relationship with the United States than it does with Venezuela, to withdraw its support. Any or all of these measures would ratchet up pressure directly on the regime, decreasing its ability to finance itself and buy support from security and military figures....

Odds are that increasing financial pressure on the regime will finally bring about its collapse.

Even if one momentarily sets aside that the sanctions are illegal under international law and violate the charter of the Organization of American States, and that the US has no right whatsoever to decide who governs Venezuela, these measures don't just "ratchet up pressure" on "the regime," they also kill and immiserate ordinary Venezuelans.A

The Post's Charles Lane (1/28/19) wrote:

Apologists for the regime blame US sanctions and destabilization for Venezuela's problems. The truth is that, with the exception of the George W. Bush administration's brief, halfhearted support for a coup attempt in 2002, Washington--learning the lessons of ill-fated Cold War interventions--has shown restraint in dealing with the Caracas regime.

He went on to write that, until the Trump administration announced limitations on imports of Venezuelan oil that day, "the United States had traded with Venezuela and focused economic pressure on regime leaders and key institutions," which suggests that the sanctions exclusively harm the "regime"--again, even if that were true, it would still be illegal--and amounts to a lie, given the evidence that the sanctions are crushing the Venezuelan masses.

Unlike Lane and the rest of the media's regime change choir, the US government has acknowledged what it's doing to Venezuela. Schiavoni, Felicien and Romero point to a telling remark that a senior State Department official made last year:

The financial sanctions we have placed on the Venezuelan Government has forced it to begin becoming in default, both on sovereign and PDVSA, its oil company's debt. And what we are seeing because of the bad choices of the Maduro regime is a total economic collapse in Venezuela. So our policy is working, our strategy is working and we're going to keep it on the Venezuelans.

Thus, the US government acknowledges that it is knowingly, consciously driving the Venezuelan economy into the ground, but US media make no such acknowledgment, which sends the message that the problems in Venezuela are entirely the fault of the government, and that the US is a neutral arbiter that wants to help Venezuelans.

Call this elision what it is: war propaganda.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

The US media chorus supporting a US overthrow of the Venezuelan government has for years pointed to the country's economic crisis as a justification for regime change, while whitewashing the ways in which the US has strangled the Venezuelan economy (FAIR.org, 3/22/18).

Sister Eugenia Russian, president of Fundalatin, a Venezuelan human rights NGO that was established in 1978 and has special consultative status at the UN, told the Independent (1/26/19):

In contact with the popular communities, we consider that one of the fundamental causes of the economic crisis in the country is the effect [of] the unilateral coercive sanctions that are applied in the economy, especially by the government of the United States.

While internal errors also contributed to the nation's problems, Russian said it's likely that few countries in the world have ever suffered an "economic siege" like the one Venezuelans are living under.

While the New York Times and the Washington Post have lately professed profound (and definitely 100 percent sincere) concern for the welfare of Venezuelans, neither publication has ever referred to Fundalatin.

Alfred de Zayas, the first UN special rapporteur to visit Venezuela in 21 years, told the Independent (1/26/19) that US, Canadian and European Union "economic warfare" has killed Venezuelans, noting that the sanctions fall most heavily on the poorest people and demonstrably cause death through food and medicine shortages, lead to violations of human rights and are aimed at coercing economic change in a "sister democracy."

De Zayas' UN report noted that sanctions "hind[er] the imports necessary to produce generic medicines and seeds to increase agricultural production." De Zayas also cited Venezuelan economist Pasqualina Curcio, who reports that "the most effective strategy to disrupt the Venezuelan economy" has been the manipulation of the exchange rate. The rapporteur went on to suggest that the International Criminal Court investigate economic sanctions against Venezuela as possible crimes against humanity.

Given that de Zayas is the first UN special rapporteur to report on Venezuela in more than two decades, one might expect the media to regard his findings as an important part of the Venezuela narrative, but his name does not appear in a single article ever published in the Post; the Times has mentioned him once, but not in relation to Venezuela.

The economist Francisco Rodriguez points out that the sanctions the Trump administration issued in August 2017 prohibited US banks from providing new financing to the Venezuelan government, a key part of the "toxification" of financial dealings with Venezuela. Rodriguez notes that, in August 2017, the US Financial Crimes Enforcement Network warned financial institutions that "all Venezuelan government agencies and bodies...appear vulnerable to public corruption and money laundering," and recommended that some transactions originating from Venezuela be flagged as potentially criminal. Many financial institutions then closed Venezuelan accounts, concerned about the risk of being accused of participating in money laundering.

Rodriguez says that this handcuffed Venezuela's oil industry, the sector most crucial to its economy, with lost access to credit preventing the country from obtaining financial resources that could have been devoted to investment or maintenance. And whereas previously the Venezuelan government would raise production by signing joint venture agreements with foreign partners who would finance investment, Trump's sanctions "effectively put an end to these loans."

Mark Weisbrot (The Nation, 9/7/17) , also an economist, raised a related issue:

If we step back and look at Venezuela from a bird's-eye view, how does a country with 500 billion barrels of oil and hundreds of billions of dollars' worth of minerals in the ground go broke? The only way that can happen is if the country is cut off from the international financial system. Otherwise, Venezuela could sell or even collateralize some of its resources in order to get the necessary dollars. The $7.7 billion in gold held in Central Bank reserves could be quickly collateralized for a loan; in past years, the US Treasury department used its clout to make sure that banks who wanted to finance a swap, such as JPMorgan Chase and Bank of America, did not do so.

Sanctions have kept the Venezuelan government from accessing financing and dealing with its debt while hamstringing its most important industry. Given that US media are writing for a principally US audience, the damage done by Washington and its partners' sanctions should be front and center in their coverage. Exactly the opposite is the case.

Virginia Lopez-Glass of the New York Times (1/25/19) uses 920 words to describe the challenges facing Venezuelans, but "sanctions" isn't one of them, even as she writes about matters to which, as I've shown above, sanctions are directly relevant: "Food and medicine shortages are widespread. Hundreds have died from malnutrition and illnesses that are easily curable with the appropriate treatment."

Weaponizing hunger in Venezuela in this manner is dishonest and misleading. Christina M. Schiavoni, a doctoral researcher at the International Institute of Social Studies in The Hague, and Ana Felicien and Liccia Romero, both of whom are Venezuelan scholars, wrote in Monthly Review (6/1/18) on "overt US aggression toward Venezuela" in the form of

the intensifying economic sanctions imposed by the Obama and Trump administrations, as well as an all-out economic blockade that has made it extremely difficult for the government to make payments on food imports and manage its debt.

Bret Stephens' column in the Times (1/28/19) only mentions the word "sanctions" to complain that the media supposedly isn't blaming "socialism" for the crisis in Venezuela, alleging that

what you're likelier to read is that the crisis is the product of corruption, cronyism, populism, authoritarianism, resource-dependency, US sanctions and trickery, even the residues of capitalism itself.

After dismissing the idea that the sanctions are a key part of the problems in Venezuela, Stephens went on to advocate using them to bring about regime change in the country, writing that the Trump administration

should enhance [Guaido]'s political standing by providing access to funds that can help him establish an alternative government and entice wavering figures in the Maduro camp to switch sides. It can put Venezuela on the list of state sponsors of terrorism.

These "funds" presumably refer the money that the US has seized from Venezuela, and adding the country to list of "state sponsors of terrorism" automatically entails hitting it with further sanctions.

The editorial board of the Washington Post (1/24/19) alleged that Venezuela's government has "subject[ed] the country's 32 million people to a humanitarian catastrophe," without referring to what scholars whose research and writing focuses on Latin America--such as Laura Carlsen, Sujatha Fernandes, Greg Grandin, Francisco Dominguez, Noam Chomsky, Aviva Chomsky, Gabriel Hetland and Venezuelan-born historian Miguel Tinker Salas--describe (Common Dreams, 1/24/19) as sanctions

cut[ting] off the means by which the Venezuelan government could escape from its economic recession, while causing a dramatic falloff in oil production and worsening the economic crisis, and causing many people to die because they can't get access to life-saving medicines.

Later, the editorial said that "a US boycott of Venezuelan oil could endanger ordinary Venezuelans already coping with critical shortages of food, power and medicine," an absurd remark given that the sanctions they are occluding have had precisely these effects.

Henry Olsen in the Post (1/24/19) wrote as if sanctions are a benign tool that can be used to usher in a brighter future for Venezuelans, rather than a key reason that so many of them find themselves in such a grim condition:

Trump has many levers to pull short of military intervention to topple Maduro. He could use US pressure on the global financial system to cut off regime access to international banks, freezing access to any secret accounts that the regime -- and, probably, its highest-ranking leaders -- established offshore. He can, as Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.) has suggested, work with American oil companies that purchase Venezuelan oil to provide the profits from those purchases to accounts controlled by Guaido's National Assembly. He can also pressure China, which has a far more valuable relationship with the United States than it does with Venezuela, to withdraw its support. Any or all of these measures would ratchet up pressure directly on the regime, decreasing its ability to finance itself and buy support from security and military figures....

Odds are that increasing financial pressure on the regime will finally bring about its collapse.

Even if one momentarily sets aside that the sanctions are illegal under international law and violate the charter of the Organization of American States, and that the US has no right whatsoever to decide who governs Venezuela, these measures don't just "ratchet up pressure" on "the regime," they also kill and immiserate ordinary Venezuelans.A

The Post's Charles Lane (1/28/19) wrote:

Apologists for the regime blame US sanctions and destabilization for Venezuela's problems. The truth is that, with the exception of the George W. Bush administration's brief, halfhearted support for a coup attempt in 2002, Washington--learning the lessons of ill-fated Cold War interventions--has shown restraint in dealing with the Caracas regime.

He went on to write that, until the Trump administration announced limitations on imports of Venezuelan oil that day, "the United States had traded with Venezuela and focused economic pressure on regime leaders and key institutions," which suggests that the sanctions exclusively harm the "regime"--again, even if that were true, it would still be illegal--and amounts to a lie, given the evidence that the sanctions are crushing the Venezuelan masses.

Unlike Lane and the rest of the media's regime change choir, the US government has acknowledged what it's doing to Venezuela. Schiavoni, Felicien and Romero point to a telling remark that a senior State Department official made last year:

The financial sanctions we have placed on the Venezuelan Government has forced it to begin becoming in default, both on sovereign and PDVSA, its oil company's debt. And what we are seeing because of the bad choices of the Maduro regime is a total economic collapse in Venezuela. So our policy is working, our strategy is working and we're going to keep it on the Venezuelans.

Thus, the US government acknowledges that it is knowingly, consciously driving the Venezuelan economy into the ground, but US media make no such acknowledgment, which sends the message that the problems in Venezuela are entirely the fault of the government, and that the US is a neutral arbiter that wants to help Venezuelans.

Call this elision what it is: war propaganda.

The US media chorus supporting a US overthrow of the Venezuelan government has for years pointed to the country's economic crisis as a justification for regime change, while whitewashing the ways in which the US has strangled the Venezuelan economy (FAIR.org, 3/22/18).

Sister Eugenia Russian, president of Fundalatin, a Venezuelan human rights NGO that was established in 1978 and has special consultative status at the UN, told the Independent (1/26/19):

In contact with the popular communities, we consider that one of the fundamental causes of the economic crisis in the country is the effect [of] the unilateral coercive sanctions that are applied in the economy, especially by the government of the United States.

While internal errors also contributed to the nation's problems, Russian said it's likely that few countries in the world have ever suffered an "economic siege" like the one Venezuelans are living under.

While the New York Times and the Washington Post have lately professed profound (and definitely 100 percent sincere) concern for the welfare of Venezuelans, neither publication has ever referred to Fundalatin.

Alfred de Zayas, the first UN special rapporteur to visit Venezuela in 21 years, told the Independent (1/26/19) that US, Canadian and European Union "economic warfare" has killed Venezuelans, noting that the sanctions fall most heavily on the poorest people and demonstrably cause death through food and medicine shortages, lead to violations of human rights and are aimed at coercing economic change in a "sister democracy."

De Zayas' UN report noted that sanctions "hind[er] the imports necessary to produce generic medicines and seeds to increase agricultural production." De Zayas also cited Venezuelan economist Pasqualina Curcio, who reports that "the most effective strategy to disrupt the Venezuelan economy" has been the manipulation of the exchange rate. The rapporteur went on to suggest that the International Criminal Court investigate economic sanctions against Venezuela as possible crimes against humanity.

Given that de Zayas is the first UN special rapporteur to report on Venezuela in more than two decades, one might expect the media to regard his findings as an important part of the Venezuela narrative, but his name does not appear in a single article ever published in the Post; the Times has mentioned him once, but not in relation to Venezuela.

The economist Francisco Rodriguez points out that the sanctions the Trump administration issued in August 2017 prohibited US banks from providing new financing to the Venezuelan government, a key part of the "toxification" of financial dealings with Venezuela. Rodriguez notes that, in August 2017, the US Financial Crimes Enforcement Network warned financial institutions that "all Venezuelan government agencies and bodies...appear vulnerable to public corruption and money laundering," and recommended that some transactions originating from Venezuela be flagged as potentially criminal. Many financial institutions then closed Venezuelan accounts, concerned about the risk of being accused of participating in money laundering.

Rodriguez says that this handcuffed Venezuela's oil industry, the sector most crucial to its economy, with lost access to credit preventing the country from obtaining financial resources that could have been devoted to investment or maintenance. And whereas previously the Venezuelan government would raise production by signing joint venture agreements with foreign partners who would finance investment, Trump's sanctions "effectively put an end to these loans."

Mark Weisbrot (The Nation, 9/7/17) , also an economist, raised a related issue:

If we step back and look at Venezuela from a bird's-eye view, how does a country with 500 billion barrels of oil and hundreds of billions of dollars' worth of minerals in the ground go broke? The only way that can happen is if the country is cut off from the international financial system. Otherwise, Venezuela could sell or even collateralize some of its resources in order to get the necessary dollars. The $7.7 billion in gold held in Central Bank reserves could be quickly collateralized for a loan; in past years, the US Treasury department used its clout to make sure that banks who wanted to finance a swap, such as JPMorgan Chase and Bank of America, did not do so.

Sanctions have kept the Venezuelan government from accessing financing and dealing with its debt while hamstringing its most important industry. Given that US media are writing for a principally US audience, the damage done by Washington and its partners' sanctions should be front and center in their coverage. Exactly the opposite is the case.

Virginia Lopez-Glass of the New York Times (1/25/19) uses 920 words to describe the challenges facing Venezuelans, but "sanctions" isn't one of them, even as she writes about matters to which, as I've shown above, sanctions are directly relevant: "Food and medicine shortages are widespread. Hundreds have died from malnutrition and illnesses that are easily curable with the appropriate treatment."

Weaponizing hunger in Venezuela in this manner is dishonest and misleading. Christina M. Schiavoni, a doctoral researcher at the International Institute of Social Studies in The Hague, and Ana Felicien and Liccia Romero, both of whom are Venezuelan scholars, wrote in Monthly Review (6/1/18) on "overt US aggression toward Venezuela" in the form of

the intensifying economic sanctions imposed by the Obama and Trump administrations, as well as an all-out economic blockade that has made it extremely difficult for the government to make payments on food imports and manage its debt.

Bret Stephens' column in the Times (1/28/19) only mentions the word "sanctions" to complain that the media supposedly isn't blaming "socialism" for the crisis in Venezuela, alleging that

what you're likelier to read is that the crisis is the product of corruption, cronyism, populism, authoritarianism, resource-dependency, US sanctions and trickery, even the residues of capitalism itself.

After dismissing the idea that the sanctions are a key part of the problems in Venezuela, Stephens went on to advocate using them to bring about regime change in the country, writing that the Trump administration

should enhance [Guaido]'s political standing by providing access to funds that can help him establish an alternative government and entice wavering figures in the Maduro camp to switch sides. It can put Venezuela on the list of state sponsors of terrorism.

These "funds" presumably refer the money that the US has seized from Venezuela, and adding the country to list of "state sponsors of terrorism" automatically entails hitting it with further sanctions.

The editorial board of the Washington Post (1/24/19) alleged that Venezuela's government has "subject[ed] the country's 32 million people to a humanitarian catastrophe," without referring to what scholars whose research and writing focuses on Latin America--such as Laura Carlsen, Sujatha Fernandes, Greg Grandin, Francisco Dominguez, Noam Chomsky, Aviva Chomsky, Gabriel Hetland and Venezuelan-born historian Miguel Tinker Salas--describe (Common Dreams, 1/24/19) as sanctions

cut[ting] off the means by which the Venezuelan government could escape from its economic recession, while causing a dramatic falloff in oil production and worsening the economic crisis, and causing many people to die because they can't get access to life-saving medicines.

Later, the editorial said that "a US boycott of Venezuelan oil could endanger ordinary Venezuelans already coping with critical shortages of food, power and medicine," an absurd remark given that the sanctions they are occluding have had precisely these effects.

Henry Olsen in the Post (1/24/19) wrote as if sanctions are a benign tool that can be used to usher in a brighter future for Venezuelans, rather than a key reason that so many of them find themselves in such a grim condition:

Trump has many levers to pull short of military intervention to topple Maduro. He could use US pressure on the global financial system to cut off regime access to international banks, freezing access to any secret accounts that the regime -- and, probably, its highest-ranking leaders -- established offshore. He can, as Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.) has suggested, work with American oil companies that purchase Venezuelan oil to provide the profits from those purchases to accounts controlled by Guaido's National Assembly. He can also pressure China, which has a far more valuable relationship with the United States than it does with Venezuela, to withdraw its support. Any or all of these measures would ratchet up pressure directly on the regime, decreasing its ability to finance itself and buy support from security and military figures....

Odds are that increasing financial pressure on the regime will finally bring about its collapse.

Even if one momentarily sets aside that the sanctions are illegal under international law and violate the charter of the Organization of American States, and that the US has no right whatsoever to decide who governs Venezuela, these measures don't just "ratchet up pressure" on "the regime," they also kill and immiserate ordinary Venezuelans.A

The Post's Charles Lane (1/28/19) wrote:

Apologists for the regime blame US sanctions and destabilization for Venezuela's problems. The truth is that, with the exception of the George W. Bush administration's brief, halfhearted support for a coup attempt in 2002, Washington--learning the lessons of ill-fated Cold War interventions--has shown restraint in dealing with the Caracas regime.

He went on to write that, until the Trump administration announced limitations on imports of Venezuelan oil that day, "the United States had traded with Venezuela and focused economic pressure on regime leaders and key institutions," which suggests that the sanctions exclusively harm the "regime"--again, even if that were true, it would still be illegal--and amounts to a lie, given the evidence that the sanctions are crushing the Venezuelan masses.

Unlike Lane and the rest of the media's regime change choir, the US government has acknowledged what it's doing to Venezuela. Schiavoni, Felicien and Romero point to a telling remark that a senior State Department official made last year:

The financial sanctions we have placed on the Venezuelan Government has forced it to begin becoming in default, both on sovereign and PDVSA, its oil company's debt. And what we are seeing because of the bad choices of the Maduro regime is a total economic collapse in Venezuela. So our policy is working, our strategy is working and we're going to keep it on the Venezuelans.

Thus, the US government acknowledges that it is knowingly, consciously driving the Venezuelan economy into the ground, but US media make no such acknowledgment, which sends the message that the problems in Venezuela are entirely the fault of the government, and that the US is a neutral arbiter that wants to help Venezuelans.

Call this elision what it is: war propaganda.