Last month, the Trump administration silently slashed $213.6 million from at least 81 institutions working on teen pregnancy prevention. The cuts hit a wide variety of programs: the Choctaw Nation's initiatives to reduce teen pregnancy in Oklahoma, the University of Texas' guidance for youth in foster care, and Baltimore's Healthy Teen Network's work on an app that could answer health questions from teen girls.

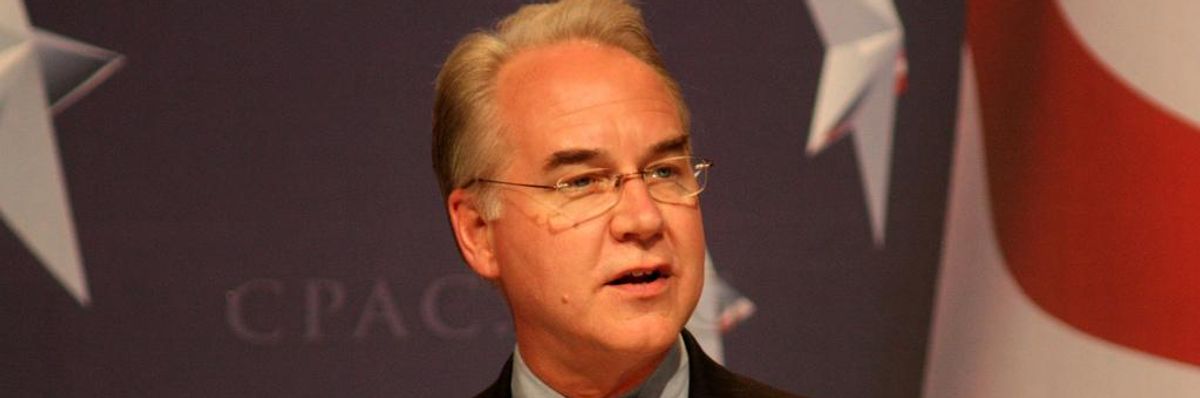

This move came at the recommendation of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), headed by Tom Price. In many ways, it's on brand with Price's career as an enthusiastic advocate for restricting women's choices: He has signed personhood acts that ban emergency contraception and abortion, opposed the Obamacare birth control mandate, tried to defund Planned Parenthood, and defended cuts to Medicaid that would deny millions of low-income women health care.

On an intellectual level, Price's cuts are frustrating because they represent another piece of a regressive puzzle the Trump administration is assembling in order to control women's choices. And personally, I'm devastated because I know what these cuts mean to the communities that they will affect.

I attended public school for my entire K-12 education in Tom Price's former district, where abstinence-only education is the norm. The single day of sex education I received promoted the idea that all sexual acts outside of a heterosexual marriage are dangerous and shameful, and did not make any distinction about whether these acts were consensual or not. It espoused gendered roles that posited women as defenders of their precious virginity, and put the responsibility on women to prevent sex from happening to them. That's perfectly in line with the content requirements for sex education in Georgia: They consciously exclude information about contraception, coercion, orientation, and HIV/AIDS, and they stress abstinence and marriage.

Because I was lucky, and because I am privileged, I was able to go to a college with real resources--extracurricular trainings, a health clinic, and actual academic courses--that helped me unlearn the detrimental sexual education I received in high school. I got the practical information that I needed, and I started unraveling my skewed concept of consent.

College gave me a second chance at sex ed, but a lot of people don't have that opportunity. For rural communities, low-income communities, and communities of color, high school sex education and community-based programs are often the only options available to acquire stigma-free, accurate education about consent, contraception, and sexual health. These populations already face myriad barriers to sex education, including culture, finances, and distance. In my home state of Georgia, there are only four Planned Parenthood clinics--one of the only affordable health centers with enough name recognition that people know to seek it out when they need help--and three of the four are located in the Atlanta metro area in the northwest corner of the state.When I attended a "Take Back the Night" rally my freshman year of college, I realized that my abstinence-only education had led me to view myself as responsible for sexual acts committed without my consent. Consequently, I felt shame instead of empowerment to take the steps I needed to recover. This is a common phenomenon for young people that experience abstinence-only education; when all expressions of sexuality are described as negative and shameful, the lines between consensual and nonconsensual acts become blurred.

Still, teen pregnancy and birth rates are at an all-time low across the country. Georgia has experienced one of the most drastic declines in these rates, from the highest teen birth rate in the United States in 1995 to the 17th in 2015. The grants that Price slashed last week were a part of that story. The target audience of all of these programs are marginalized youth who have a demonstrated need for increased education. And these are the groups that are at the greatest risk for high teen birth rates: Rural counties reported an average birth rate of 30.9 (30.9 teens per 1,000 females aged 15-19), compared with the much lower rate of 18.9 for urban counties. Similarly, black and Latino teenagers experience teen pregnancy at rates twice as high as white teenagers. For these communities, removing teen pregnancy prevention programs that these grants funded will restore the negative effects of abstinence-only education that the grants were originally provided to combat. For example, one of the programs cut was run by the Augusta Partnership for Children Inc., which focuses on reducing teen pregnancy and STI rates in four rural East Georgia counties. In one of these counties, Augusta-Richmond county, the teen birthrate is 22.9 percent higher than the state average.

It almost goes without saying that cuts to teen pregnancy prevention programs could reverse the downward trends in teen pregnancy and birth rates. And the Trump administration is attacking other lifelines marginalized groups depend on, too. Funding decreases imposed on safety net programs and Medicaid, both threatened under the Trump and congressional budgets, will significantly impact teen parents who often rely on public assistance for food, housing, and healthcare. Similarly, without sex education and community-based programs funded by HHS, teen parents and youth in general will likely need to turn toTitle X providers for contraception, abortion services, and sex education. But President Trump and congressional Republicans have been chipping away at Title X providers too, by rolling back an Obama-era regulation that prevents state and local governments from denying funding to health care providers for "political" reasons--namely, the provision of abortion services.

These cuts can't be written off as a difference in ideology. I experienced firsthand the powerlessness that results from a shaming, abstinence-focused education, and it can be a matter of life and death for communities already on the margins. I had a second chance at a more holistic education, but it was due to luck and privilege that most folks in Georgia do not have access to. And when we're talking about pregnancy, HIV/AIDS infection rates, and domestic and sexual violence, luck and privilege shouldn't be the factors we have to rely on.