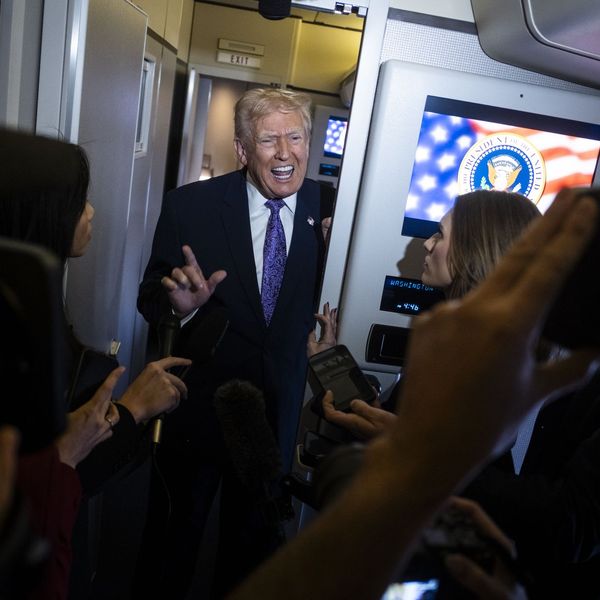

We Must Rein in President Trump's Spying Powers

It's been just over a month since Donald J. Trump assumed the enormous powers of the U.S. presidency, including the power to control the government's far-reaching surveillance of Americans and others. As we've explained elsewhere, President Trump will wield extremely broad and unconstitutional surveillance powers, with the world's most sophisticated technological tools at his disposal.

It's been just over a month since Donald J. Trump assumed the enormous powers of the U.S. presidency, including the power to control the government's far-reaching surveillance of Americans and others. As we've explained elsewhere, President Trump will wield extremely broad and unconstitutional surveillance powers, with the world's most sophisticated technological tools at his disposal. Based on his past statements and conduct, we have every reason to be concerned that he will misuse this sprawling spying apparatus.

One of these spying authorities -- Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act -- is set to expire at the end of this year, and Congress has already begun holding hearings that highlight much-needed reforms. The government uses Section 702 to examine the full contents of Americans' international emails, web-browsing, and phone calls -- all without ever getting a warrant. This surveillance violates our core rights to privacy, freedom of expression, and freedom of association guaranteed by the First and Fourth Amendments.

"Under Section 702, the government may target people who are not suspected of any wrongdoing whatsoever."

Not only does Section 702 give the government access to sensitive online communications, but this surveillance also sweeps incredibly broadly, capturing vast quantities of Americans' personal data. With the assistance of companies like Facebook, Google, AT&T, and Verizon, the government relies on Section 702 to carry out mass surveillance on U.S. soil, including both the "PRISM" and "Upstream" programs revealed by the whistleblower Edward Snowden. While the ACLU has long objected to this large-scale, warrantless spying, with President Trump now at the helm of the surveillance state, the stakes couldn't be higher. Congress must fundamentally reform this law.

To fight alongside us in demanding reform, here's what you need to know about Section 702:

Section 702 Permits the Government to "Target" Completely Innocent People

Section 702 permits the NSA, FBI, and CIA to spy on communications without a warrant when two primary conditions are met. First, the "target" of the surveillance must be a foreigner located abroad. And second, a significant purpose of the surveillance must be to gather "foreign intelligence information."

Neither of these conditions imposes a meaningful constraint on the government's ability to spy. Almost anyone abroad could be an eligible target. Indeed, Section 702 does not require the government to make any finding -- let alone demonstrate probable cause to a judge -- that its surveillance targets are agents of a foreign power, engaged in criminal activity, or even remotely associated with terrorism. (Instead, judges on a secret intelligence court approve only the general procedures that government analysts are supposed to follow.) In addition, the law defines the term "foreign intelligence" broadly -- so broadly that the surveillance could readily include communications by journalists, human rights workers, whistleblowers, and virtually anyone else talking about foreign affairs. As a result, low-level NSA analysts have tremendous discretion in selecting whom to target.

In other words, under Section 702, the government may target people who are not suspected of any wrongdoing whatsoever. Given how few constraints apply, it's hardly surprising that at last count the NSA was using this law to surveil almost 100,000 people, organizations, and groups. Americans who call or email with these thousands of targets -- whether they are family members, friends, or colleagues -- have their communications swept up too.

The Government Uses Section 702 to Conduct Bulk Searches of Our Online Communications

One other crucial feature of this surveillance was hidden from the public for years and goes far beyond what the statute permits: The government is using Section 702 to engage in bulk searches of Americans' online communications.

"There's nothing 'targeted' about a surveillance program that subjects millions of Americans to suspicionless government searches of their communications."

Under the "Upstream" program revealed by Snowden, the government is searching the contents of international internet communications in real-time, looking for references to its many targets. (This is sometimes called "about" surveillance, because it involves combing through the full text of communications in search of those that are merely about a target.) With the compelled assistance of companies like AT&T and Verizon, the NSA has installed surveillance equipment at dozens of points along the internet "backbone," the network of high-capacity cables, switches, and routers that carry your email, web browsing, and other internet communications. The NSA systematically copies and searches the contents of substantially all the international communications flowing past those surveillance devices.

This is precisely the kind of general search that the Fourth Amendment was intended to prohibit. While the government often claims this surveillance is "targeted," it's playing word games. The NSA effectively opens and reads international communications to and from everyone, in search of those that mention, for instance, a target's email address or phone number. That's essentially like opening every letter that passes through the mail in search of a particular name. There's nothing "targeted" about a surveillance program that subjects millions of Americans to suspicionless government searches of their communications.

The Government Uses Section 702 to Investigate Americans

The government justifies warrantless Section 702 surveillance on the theory that this spying is directed at foreigners -- but, once the information is collected, the government routinely trains its sights on Americans instead. The government stores hundreds of millions of communications collected under Section 702 in NSA, CIA, and FBI databases. Then, relying on what's known as the "backdoor search" loophole, analysts use Americans' names and other identifying information to retrieve and examine individuals' private communications. The government employs this technique in ordinary criminal investigations and trials that are unrelated to national security, even though the communications were collected without a warrant. In short, the backdoor search loophole functions as an end-run around the Fourth Amendment.

In the coming year, Congress can and must remedy each of these profound problems with Section 702 spying. While the ACLU is currently challenging this surveillance in civil and criminal cases, we're also fighting for reform in the legislative branch, and we'll need your help. Sign up for ACLU action alerts today, so that you can easily contact your legislators as they consider how to rein in President Trump's NSA.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

It's been just over a month since Donald J. Trump assumed the enormous powers of the U.S. presidency, including the power to control the government's far-reaching surveillance of Americans and others. As we've explained elsewhere, President Trump will wield extremely broad and unconstitutional surveillance powers, with the world's most sophisticated technological tools at his disposal. Based on his past statements and conduct, we have every reason to be concerned that he will misuse this sprawling spying apparatus.

One of these spying authorities -- Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act -- is set to expire at the end of this year, and Congress has already begun holding hearings that highlight much-needed reforms. The government uses Section 702 to examine the full contents of Americans' international emails, web-browsing, and phone calls -- all without ever getting a warrant. This surveillance violates our core rights to privacy, freedom of expression, and freedom of association guaranteed by the First and Fourth Amendments.

"Under Section 702, the government may target people who are not suspected of any wrongdoing whatsoever."

Not only does Section 702 give the government access to sensitive online communications, but this surveillance also sweeps incredibly broadly, capturing vast quantities of Americans' personal data. With the assistance of companies like Facebook, Google, AT&T, and Verizon, the government relies on Section 702 to carry out mass surveillance on U.S. soil, including both the "PRISM" and "Upstream" programs revealed by the whistleblower Edward Snowden. While the ACLU has long objected to this large-scale, warrantless spying, with President Trump now at the helm of the surveillance state, the stakes couldn't be higher. Congress must fundamentally reform this law.

To fight alongside us in demanding reform, here's what you need to know about Section 702:

Section 702 Permits the Government to "Target" Completely Innocent People

Section 702 permits the NSA, FBI, and CIA to spy on communications without a warrant when two primary conditions are met. First, the "target" of the surveillance must be a foreigner located abroad. And second, a significant purpose of the surveillance must be to gather "foreign intelligence information."

Neither of these conditions imposes a meaningful constraint on the government's ability to spy. Almost anyone abroad could be an eligible target. Indeed, Section 702 does not require the government to make any finding -- let alone demonstrate probable cause to a judge -- that its surveillance targets are agents of a foreign power, engaged in criminal activity, or even remotely associated with terrorism. (Instead, judges on a secret intelligence court approve only the general procedures that government analysts are supposed to follow.) In addition, the law defines the term "foreign intelligence" broadly -- so broadly that the surveillance could readily include communications by journalists, human rights workers, whistleblowers, and virtually anyone else talking about foreign affairs. As a result, low-level NSA analysts have tremendous discretion in selecting whom to target.

In other words, under Section 702, the government may target people who are not suspected of any wrongdoing whatsoever. Given how few constraints apply, it's hardly surprising that at last count the NSA was using this law to surveil almost 100,000 people, organizations, and groups. Americans who call or email with these thousands of targets -- whether they are family members, friends, or colleagues -- have their communications swept up too.

The Government Uses Section 702 to Conduct Bulk Searches of Our Online Communications

One other crucial feature of this surveillance was hidden from the public for years and goes far beyond what the statute permits: The government is using Section 702 to engage in bulk searches of Americans' online communications.

"There's nothing 'targeted' about a surveillance program that subjects millions of Americans to suspicionless government searches of their communications."

Under the "Upstream" program revealed by Snowden, the government is searching the contents of international internet communications in real-time, looking for references to its many targets. (This is sometimes called "about" surveillance, because it involves combing through the full text of communications in search of those that are merely about a target.) With the compelled assistance of companies like AT&T and Verizon, the NSA has installed surveillance equipment at dozens of points along the internet "backbone," the network of high-capacity cables, switches, and routers that carry your email, web browsing, and other internet communications. The NSA systematically copies and searches the contents of substantially all the international communications flowing past those surveillance devices.

This is precisely the kind of general search that the Fourth Amendment was intended to prohibit. While the government often claims this surveillance is "targeted," it's playing word games. The NSA effectively opens and reads international communications to and from everyone, in search of those that mention, for instance, a target's email address or phone number. That's essentially like opening every letter that passes through the mail in search of a particular name. There's nothing "targeted" about a surveillance program that subjects millions of Americans to suspicionless government searches of their communications.

The Government Uses Section 702 to Investigate Americans

The government justifies warrantless Section 702 surveillance on the theory that this spying is directed at foreigners -- but, once the information is collected, the government routinely trains its sights on Americans instead. The government stores hundreds of millions of communications collected under Section 702 in NSA, CIA, and FBI databases. Then, relying on what's known as the "backdoor search" loophole, analysts use Americans' names and other identifying information to retrieve and examine individuals' private communications. The government employs this technique in ordinary criminal investigations and trials that are unrelated to national security, even though the communications were collected without a warrant. In short, the backdoor search loophole functions as an end-run around the Fourth Amendment.

In the coming year, Congress can and must remedy each of these profound problems with Section 702 spying. While the ACLU is currently challenging this surveillance in civil and criminal cases, we're also fighting for reform in the legislative branch, and we'll need your help. Sign up for ACLU action alerts today, so that you can easily contact your legislators as they consider how to rein in President Trump's NSA.

It's been just over a month since Donald J. Trump assumed the enormous powers of the U.S. presidency, including the power to control the government's far-reaching surveillance of Americans and others. As we've explained elsewhere, President Trump will wield extremely broad and unconstitutional surveillance powers, with the world's most sophisticated technological tools at his disposal. Based on his past statements and conduct, we have every reason to be concerned that he will misuse this sprawling spying apparatus.

One of these spying authorities -- Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act -- is set to expire at the end of this year, and Congress has already begun holding hearings that highlight much-needed reforms. The government uses Section 702 to examine the full contents of Americans' international emails, web-browsing, and phone calls -- all without ever getting a warrant. This surveillance violates our core rights to privacy, freedom of expression, and freedom of association guaranteed by the First and Fourth Amendments.

"Under Section 702, the government may target people who are not suspected of any wrongdoing whatsoever."

Not only does Section 702 give the government access to sensitive online communications, but this surveillance also sweeps incredibly broadly, capturing vast quantities of Americans' personal data. With the assistance of companies like Facebook, Google, AT&T, and Verizon, the government relies on Section 702 to carry out mass surveillance on U.S. soil, including both the "PRISM" and "Upstream" programs revealed by the whistleblower Edward Snowden. While the ACLU has long objected to this large-scale, warrantless spying, with President Trump now at the helm of the surveillance state, the stakes couldn't be higher. Congress must fundamentally reform this law.

To fight alongside us in demanding reform, here's what you need to know about Section 702:

Section 702 Permits the Government to "Target" Completely Innocent People

Section 702 permits the NSA, FBI, and CIA to spy on communications without a warrant when two primary conditions are met. First, the "target" of the surveillance must be a foreigner located abroad. And second, a significant purpose of the surveillance must be to gather "foreign intelligence information."

Neither of these conditions imposes a meaningful constraint on the government's ability to spy. Almost anyone abroad could be an eligible target. Indeed, Section 702 does not require the government to make any finding -- let alone demonstrate probable cause to a judge -- that its surveillance targets are agents of a foreign power, engaged in criminal activity, or even remotely associated with terrorism. (Instead, judges on a secret intelligence court approve only the general procedures that government analysts are supposed to follow.) In addition, the law defines the term "foreign intelligence" broadly -- so broadly that the surveillance could readily include communications by journalists, human rights workers, whistleblowers, and virtually anyone else talking about foreign affairs. As a result, low-level NSA analysts have tremendous discretion in selecting whom to target.

In other words, under Section 702, the government may target people who are not suspected of any wrongdoing whatsoever. Given how few constraints apply, it's hardly surprising that at last count the NSA was using this law to surveil almost 100,000 people, organizations, and groups. Americans who call or email with these thousands of targets -- whether they are family members, friends, or colleagues -- have their communications swept up too.

The Government Uses Section 702 to Conduct Bulk Searches of Our Online Communications

One other crucial feature of this surveillance was hidden from the public for years and goes far beyond what the statute permits: The government is using Section 702 to engage in bulk searches of Americans' online communications.

"There's nothing 'targeted' about a surveillance program that subjects millions of Americans to suspicionless government searches of their communications."

Under the "Upstream" program revealed by Snowden, the government is searching the contents of international internet communications in real-time, looking for references to its many targets. (This is sometimes called "about" surveillance, because it involves combing through the full text of communications in search of those that are merely about a target.) With the compelled assistance of companies like AT&T and Verizon, the NSA has installed surveillance equipment at dozens of points along the internet "backbone," the network of high-capacity cables, switches, and routers that carry your email, web browsing, and other internet communications. The NSA systematically copies and searches the contents of substantially all the international communications flowing past those surveillance devices.

This is precisely the kind of general search that the Fourth Amendment was intended to prohibit. While the government often claims this surveillance is "targeted," it's playing word games. The NSA effectively opens and reads international communications to and from everyone, in search of those that mention, for instance, a target's email address or phone number. That's essentially like opening every letter that passes through the mail in search of a particular name. There's nothing "targeted" about a surveillance program that subjects millions of Americans to suspicionless government searches of their communications.

The Government Uses Section 702 to Investigate Americans

The government justifies warrantless Section 702 surveillance on the theory that this spying is directed at foreigners -- but, once the information is collected, the government routinely trains its sights on Americans instead. The government stores hundreds of millions of communications collected under Section 702 in NSA, CIA, and FBI databases. Then, relying on what's known as the "backdoor search" loophole, analysts use Americans' names and other identifying information to retrieve and examine individuals' private communications. The government employs this technique in ordinary criminal investigations and trials that are unrelated to national security, even though the communications were collected without a warrant. In short, the backdoor search loophole functions as an end-run around the Fourth Amendment.

In the coming year, Congress can and must remedy each of these profound problems with Section 702 spying. While the ACLU is currently challenging this surveillance in civil and criminal cases, we're also fighting for reform in the legislative branch, and we'll need your help. Sign up for ACLU action alerts today, so that you can easily contact your legislators as they consider how to rein in President Trump's NSA.