Sanders Challenges Neoliberal Stranglehold with Call for Free Higher Education

This campaign, and the broader movement it is helping to galvanize, has the potential to shift the terms of political debate from privileging Wall Street’s interests to concentrating the demands of working and middle-class people

The recent New York Times op-ed by N. Gregory Mankiw, "Three Reasons for Those Hefty College Tuition Bills," is pure ideological huffing and puffing of the sort we'd expect from a former chair of George W. Bush's Council of Economic Advisors. It's just a bushel of the same old free-market shibboleths typically invoked to dismiss out of hand any position that doesn't comport with the market fundamentalist perspective on the world.

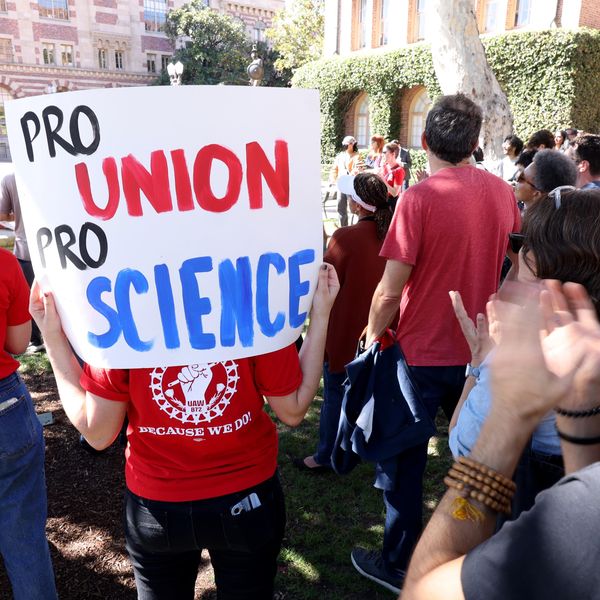

First, although this point may not seem to line up directly with the argument for free public higher education, the relationship between educational attainment and income is at best more complicated than Mankiw claims, and he is in an important sense just wrong. For most workers unionization is probably a more significant determinant of income and quality of employment than is post-secondary educational attainment. The utilitarian argument that justifies pursuit of higher education as preparation for employment is faulty partly because it rests on flimflam about the economic impact of technology. Technological innovation is at least as likely to deskill--to produce low-skill, low-wage jobs--as it is to generate new higher paying jobs with greater skill requirements. (Think of commercial "innovations" like Grubhub and delivery.com, that make it possible to get a sandwich at whim any hour of day or night with minimal human contact, or Uber; the hype of technosavvy convenience conceals the reality that what makes those services work effectively is highly exploited labor.)

"Sanders has made clear that access to higher education should be available to all, so far as interest and demonstrated performance can take them, as a right - without regard to ability to pay."

Indeed, the technological innovations in higher education that Mankiw mentions are primarily about displacing and degrading academic labor - speeding up faculty workloads and intensifying the shift to contingent, horribly underpaid and exploited adjunct faculty positions. Even he notes that these innovations do not translate into improved teaching and learning. He observes that "the ideal experience for a student is a small class that fosters personal interaction with a dedicated instructor," which is precisely the pedagogical approach those innovations, beneath a breathless patter of technofetishism, undermine.

Moreover, the utilitarian argument fails on its own terms because, although some fields--e.g., medicine, engineering, etc.--do require specialized post-secondary education as necessary preparation for operating as a professional, very many others do not.

According to a 2012 report from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), only about 20% of jobs in the American economy require a college degree, and, technofetishism notwithstanding, that percentage is projected to increase only very marginally (to 20.5%) by 2020. To reinforce the point, the BLS report estimates that the two fastest growing job categories by percentage are "personal care aides" and "home health aides," jobs that that are classified as low-skill, requiring "less than high school" educational attainment, and are paid low wages. (It is a travesty that the labor of those workers who provide direct care for people who are chronically ill, disabled and elderly is so grievously devalued, but the key issue here is that those most rapidly growing job categories do not require college attendance, much less graduation, which indeed would probably deem an applicant "overqualified.") Moreover, even when listed as a requirement for employment, possession of a higher education credential is commonly not necessary for performance of a particular job but functions instead as an employment screen, a largely arbitrary criterion for exclusion, not unlike how race and gender have functioned historically. From that perspective, the apparent connection between possession of a higher education credential and income depends on not everyone having access to college and university study. If more people had access, a college degree would lose its effectiveness as an employment screen. This contradiction in Mankiw's contention is yet another expression of free-market ideologues' ability to see only congeries of isolated individuals and not the social aggregate.

Many advocates of expanding access to higher education, including progressives, nonetheless have found the human capital argument--that college education improves earning power--seductive because it seems to provide a practical, noncontroversial justification for the importance of college, but that argument is problematic on its merits for the reasons I've indicated. And it no longer has even the rhetorical force it once seemed to have for defending higher education as a social good. At this point the utilitarian, employment-related view of higher education is deployed much more effectively by the private, non-profit entities that reduce higher education to a bogus simulacrum of job training and stimulate a race to the bottom in the higher ed field in general. In this regard, one very important feature of Senator Bernie Sanders's College For All Act (S. 1373) is that it calls for increasing numbers and percentages of full-time faculty and improved salary and working conditions for part-time or contingent faculty. Guaranteeing access to higher education as a right means not only eliminating ability to pay as a limitation; it also must mean providing the material conditions under which high quality college and university education can occur, and those include the economic and intellectual security of faculty.

Another clear illustration of Mankiw's ideological bias is that he simply dismisses the fact that the College For All Act favors "government-run over private colleges" as a weakness. Not only are there no "government-run" colleges, except perhaps the service academies; Mankiw provides no reason for his assertion, but we can only assume that his point is that public goods are by definition inferior to those produced through private market forces. He also insists that under the College For All Act tuition wouldn't be free; its cost would only be shifted from individual students to generic taxpayers. This contention is consistent with the right-wing view that government provision of public goods and services amounts to a tyrannical imposition on individuals who should be able to choose the bundles of amenities that would satisfy their needs and desires in the private market.

Mankiw's preferred alternative underscores that bias. He rehearses the proposal long advocated by the ultra-right wing Cato Institute, now apparently touted by Marco Rubio, that funding college tuition should be entirely privatized, that prospective students should appeal to venture capitalists who would lend them money for tuition against a promise to a portion of future earnings. Such a system would further marketize higher education, making ability to finance college dependent on a venture capitalist's capricious assessment of future earning power based on little more than the prestige of the institution at which prospective students intend to matriculate and the courses of study they intend to follow.

This proposal underscores what Mankiw is either ideologically blind to or disingenuously chooses not to admit. Sen. Sanders's vision of higher education is fundamentally different from and at odds with his. Sanders has made clear that access to higher education should be available to all, so far as interest and demonstrated performance can take them, as a right - without regard to ability to pay. Mankiw mentions that Sanders proposes that access to higher education should be a right, but he does not argue with that proposition or even discuss its implications. He simply responds with assertions scooped from the grab bag of free-market bromides. Either way, Mankiw's tack is unfortunate. It could be useful to have an open discussion of the different visions of the good society from which Sanders' and his approaches to improving access to higher education emerge. Instead, Mankiw concludes with the stale canard, the classic academic's obfuscation that "there are no easy answers here." He's wrong; the answers to how to address the intensifying crisis in access to higher education are almost laughably easy, and are laid out clearly in Sanders' College For All Act. It would have been interesting had Prof. Mankiw been of a mind to debate it on its merits because this is a moment that calls out in a particularly sharp way for debate over fundamental visions of how the society should be governed, which values and interests should take priority in American political life. Assessing the different approaches to interpreting and addressing the deepening crisis in access to higher provides a clear view of the contending values and priorities that face us.

"At this juncture in American politics we need to assert a political vision unequivocally animated by the spirit in FDR's Second Bill of Rights."

Prof. Mankiw sees market rationality as the only defensible social ideal. He opposes the notion that government has a responsibility for protecting and enhancing the social welfare. This is the ideal of capitalist predators, which reigned absolutely in this country until the social insurgencies of the last two-thirds of the twentieth century won protections for working people that were institutionalized as law and social policy. The fruit of those victories have been under relentless attack for nearly forty years now. That attack has been increasingly bipartisan, as both Clinton and Obama administrations have retreated from the conviction exemplified in Franklin Delano Roosevelt's Second Bill of Rights, which could be enforced and sustained only by government. These included:

- The right to a useful and remunerative job in the industries or shops or farms or mines of the nation;

- The right to earn enough to provide adequate food and clothing and recreation;

- The right of every farmer to raise and sell his products at a return which will give him and his family a decent living;

- The right of every businessman, large and small, to trade in an atmosphere of freedom from unfair competition and domination by monopolies at home or abroad;

- The right of every family to a decent home;

- The right to adequate medical care and the opportunity to achieve and enjoy good health;

- The right to adequate protection from the economic fears of old age, sickness, accident, and unemployment;

- The right to a good education.

All of these rights spell security. And after this war is won we must be prepared to move forward, in the implementation of these rights, to new goals of human happiness and well-being.

"After this war is won we must be prepared to move forward, in the implementation of these rights, to new goals of human happiness and well-being."

At this juncture in American politics we need to assert a political vision unequivocally animated by the spirit in FDR's Second Bill of Rights. It is time for us to demand an agenda that proceeds from a concrete sense of what the country would look like, what the thrust of public policy would be, if the interests and real, felt concerns of the vast majority of working and middle-class people were the central priority of our national government. Senator Sanders's campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination has put that possibility in the public spotlight. I can attest to that personally. After having spent nearly fifteen years agitating for free public higher education as a political objective, I've found it more than exciting to see that the campaign has put the issue, through the College For All Act, on the table for national discussion.

The Sanders campaign has the potential to do much more to shift the terms of political debate from privileging Wall Street's interests to focus on those of working people - among other things, to galvanize public support for postal banking and full commitment to funding the United States Postal Service, to fight for real national health care on a single-payer model, to undo erroneously named "trade" agreements that are really about strengthening corporate power and driving down workers' living standards here and elsewhere, to address the environmental crisis in a serious way, to push for massive increases in public investment to stimulate real full employment and to rebuild crumbling social and physical infrastructure, and to eliminate the hideous disgrace of mass incarceration and the terroristic forms of neoliberal policing associated with it. Only the Sanders campaign embraces those objectives forcefully and on principle, and only the Sanders campaign has the capacity to build the sort of broadly based working and middle class alliance--on the basis of frank appeal to common interests across all the other seeming bases of division--essential for this program to become a reality.The other side is aware of this potential and therefore its minions like Mankiw are stepping up attacks.

Is it possible to build a popular movement strong and serious enough to withstand those attacks, whether they come from Republicans or other Democrats? I believe it is, but only if we work for it.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Adolph Reed, Jr. is Professor Emeritus of Political Science at the University of Pennsylvania and Distinguished Visiting Professor of Politics at Mount Holyoke College. His most recent book, co-authored with Kenneth W. Warren is Black Studies, Cultural Politics and the Evasion of Inequality: The Farce This Time (Routledge, 2025). Previous books include: No Politics But Class Politics (with Walter Benn Michaels / 2023); The South: Jim Crow and Its Afterlives (2022); and Class Notes: Posing As Politics and Other Thoughts on the American Scene (2000).

The recent New York Times op-ed by N. Gregory Mankiw, "Three Reasons for Those Hefty College Tuition Bills," is pure ideological huffing and puffing of the sort we'd expect from a former chair of George W. Bush's Council of Economic Advisors. It's just a bushel of the same old free-market shibboleths typically invoked to dismiss out of hand any position that doesn't comport with the market fundamentalist perspective on the world.

First, although this point may not seem to line up directly with the argument for free public higher education, the relationship between educational attainment and income is at best more complicated than Mankiw claims, and he is in an important sense just wrong. For most workers unionization is probably a more significant determinant of income and quality of employment than is post-secondary educational attainment. The utilitarian argument that justifies pursuit of higher education as preparation for employment is faulty partly because it rests on flimflam about the economic impact of technology. Technological innovation is at least as likely to deskill--to produce low-skill, low-wage jobs--as it is to generate new higher paying jobs with greater skill requirements. (Think of commercial "innovations" like Grubhub and delivery.com, that make it possible to get a sandwich at whim any hour of day or night with minimal human contact, or Uber; the hype of technosavvy convenience conceals the reality that what makes those services work effectively is highly exploited labor.)

"Sanders has made clear that access to higher education should be available to all, so far as interest and demonstrated performance can take them, as a right - without regard to ability to pay."

Indeed, the technological innovations in higher education that Mankiw mentions are primarily about displacing and degrading academic labor - speeding up faculty workloads and intensifying the shift to contingent, horribly underpaid and exploited adjunct faculty positions. Even he notes that these innovations do not translate into improved teaching and learning. He observes that "the ideal experience for a student is a small class that fosters personal interaction with a dedicated instructor," which is precisely the pedagogical approach those innovations, beneath a breathless patter of technofetishism, undermine.

Moreover, the utilitarian argument fails on its own terms because, although some fields--e.g., medicine, engineering, etc.--do require specialized post-secondary education as necessary preparation for operating as a professional, very many others do not.

According to a 2012 report from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), only about 20% of jobs in the American economy require a college degree, and, technofetishism notwithstanding, that percentage is projected to increase only very marginally (to 20.5%) by 2020. To reinforce the point, the BLS report estimates that the two fastest growing job categories by percentage are "personal care aides" and "home health aides," jobs that that are classified as low-skill, requiring "less than high school" educational attainment, and are paid low wages. (It is a travesty that the labor of those workers who provide direct care for people who are chronically ill, disabled and elderly is so grievously devalued, but the key issue here is that those most rapidly growing job categories do not require college attendance, much less graduation, which indeed would probably deem an applicant "overqualified.") Moreover, even when listed as a requirement for employment, possession of a higher education credential is commonly not necessary for performance of a particular job but functions instead as an employment screen, a largely arbitrary criterion for exclusion, not unlike how race and gender have functioned historically. From that perspective, the apparent connection between possession of a higher education credential and income depends on not everyone having access to college and university study. If more people had access, a college degree would lose its effectiveness as an employment screen. This contradiction in Mankiw's contention is yet another expression of free-market ideologues' ability to see only congeries of isolated individuals and not the social aggregate.

Many advocates of expanding access to higher education, including progressives, nonetheless have found the human capital argument--that college education improves earning power--seductive because it seems to provide a practical, noncontroversial justification for the importance of college, but that argument is problematic on its merits for the reasons I've indicated. And it no longer has even the rhetorical force it once seemed to have for defending higher education as a social good. At this point the utilitarian, employment-related view of higher education is deployed much more effectively by the private, non-profit entities that reduce higher education to a bogus simulacrum of job training and stimulate a race to the bottom in the higher ed field in general. In this regard, one very important feature of Senator Bernie Sanders's College For All Act (S. 1373) is that it calls for increasing numbers and percentages of full-time faculty and improved salary and working conditions for part-time or contingent faculty. Guaranteeing access to higher education as a right means not only eliminating ability to pay as a limitation; it also must mean providing the material conditions under which high quality college and university education can occur, and those include the economic and intellectual security of faculty.

Another clear illustration of Mankiw's ideological bias is that he simply dismisses the fact that the College For All Act favors "government-run over private colleges" as a weakness. Not only are there no "government-run" colleges, except perhaps the service academies; Mankiw provides no reason for his assertion, but we can only assume that his point is that public goods are by definition inferior to those produced through private market forces. He also insists that under the College For All Act tuition wouldn't be free; its cost would only be shifted from individual students to generic taxpayers. This contention is consistent with the right-wing view that government provision of public goods and services amounts to a tyrannical imposition on individuals who should be able to choose the bundles of amenities that would satisfy their needs and desires in the private market.

Mankiw's preferred alternative underscores that bias. He rehearses the proposal long advocated by the ultra-right wing Cato Institute, now apparently touted by Marco Rubio, that funding college tuition should be entirely privatized, that prospective students should appeal to venture capitalists who would lend them money for tuition against a promise to a portion of future earnings. Such a system would further marketize higher education, making ability to finance college dependent on a venture capitalist's capricious assessment of future earning power based on little more than the prestige of the institution at which prospective students intend to matriculate and the courses of study they intend to follow.

This proposal underscores what Mankiw is either ideologically blind to or disingenuously chooses not to admit. Sen. Sanders's vision of higher education is fundamentally different from and at odds with his. Sanders has made clear that access to higher education should be available to all, so far as interest and demonstrated performance can take them, as a right - without regard to ability to pay. Mankiw mentions that Sanders proposes that access to higher education should be a right, but he does not argue with that proposition or even discuss its implications. He simply responds with assertions scooped from the grab bag of free-market bromides. Either way, Mankiw's tack is unfortunate. It could be useful to have an open discussion of the different visions of the good society from which Sanders' and his approaches to improving access to higher education emerge. Instead, Mankiw concludes with the stale canard, the classic academic's obfuscation that "there are no easy answers here." He's wrong; the answers to how to address the intensifying crisis in access to higher education are almost laughably easy, and are laid out clearly in Sanders' College For All Act. It would have been interesting had Prof. Mankiw been of a mind to debate it on its merits because this is a moment that calls out in a particularly sharp way for debate over fundamental visions of how the society should be governed, which values and interests should take priority in American political life. Assessing the different approaches to interpreting and addressing the deepening crisis in access to higher provides a clear view of the contending values and priorities that face us.

"At this juncture in American politics we need to assert a political vision unequivocally animated by the spirit in FDR's Second Bill of Rights."

Prof. Mankiw sees market rationality as the only defensible social ideal. He opposes the notion that government has a responsibility for protecting and enhancing the social welfare. This is the ideal of capitalist predators, which reigned absolutely in this country until the social insurgencies of the last two-thirds of the twentieth century won protections for working people that were institutionalized as law and social policy. The fruit of those victories have been under relentless attack for nearly forty years now. That attack has been increasingly bipartisan, as both Clinton and Obama administrations have retreated from the conviction exemplified in Franklin Delano Roosevelt's Second Bill of Rights, which could be enforced and sustained only by government. These included:

- The right to a useful and remunerative job in the industries or shops or farms or mines of the nation;

- The right to earn enough to provide adequate food and clothing and recreation;

- The right of every farmer to raise and sell his products at a return which will give him and his family a decent living;

- The right of every businessman, large and small, to trade in an atmosphere of freedom from unfair competition and domination by monopolies at home or abroad;

- The right of every family to a decent home;

- The right to adequate medical care and the opportunity to achieve and enjoy good health;

- The right to adequate protection from the economic fears of old age, sickness, accident, and unemployment;

- The right to a good education.

All of these rights spell security. And after this war is won we must be prepared to move forward, in the implementation of these rights, to new goals of human happiness and well-being.

"After this war is won we must be prepared to move forward, in the implementation of these rights, to new goals of human happiness and well-being."

At this juncture in American politics we need to assert a political vision unequivocally animated by the spirit in FDR's Second Bill of Rights. It is time for us to demand an agenda that proceeds from a concrete sense of what the country would look like, what the thrust of public policy would be, if the interests and real, felt concerns of the vast majority of working and middle-class people were the central priority of our national government. Senator Sanders's campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination has put that possibility in the public spotlight. I can attest to that personally. After having spent nearly fifteen years agitating for free public higher education as a political objective, I've found it more than exciting to see that the campaign has put the issue, through the College For All Act, on the table for national discussion.

The Sanders campaign has the potential to do much more to shift the terms of political debate from privileging Wall Street's interests to focus on those of working people - among other things, to galvanize public support for postal banking and full commitment to funding the United States Postal Service, to fight for real national health care on a single-payer model, to undo erroneously named "trade" agreements that are really about strengthening corporate power and driving down workers' living standards here and elsewhere, to address the environmental crisis in a serious way, to push for massive increases in public investment to stimulate real full employment and to rebuild crumbling social and physical infrastructure, and to eliminate the hideous disgrace of mass incarceration and the terroristic forms of neoliberal policing associated with it. Only the Sanders campaign embraces those objectives forcefully and on principle, and only the Sanders campaign has the capacity to build the sort of broadly based working and middle class alliance--on the basis of frank appeal to common interests across all the other seeming bases of division--essential for this program to become a reality.The other side is aware of this potential and therefore its minions like Mankiw are stepping up attacks.

Is it possible to build a popular movement strong and serious enough to withstand those attacks, whether they come from Republicans or other Democrats? I believe it is, but only if we work for it.

Adolph Reed, Jr. is Professor Emeritus of Political Science at the University of Pennsylvania and Distinguished Visiting Professor of Politics at Mount Holyoke College. His most recent book, co-authored with Kenneth W. Warren is Black Studies, Cultural Politics and the Evasion of Inequality: The Farce This Time (Routledge, 2025). Previous books include: No Politics But Class Politics (with Walter Benn Michaels / 2023); The South: Jim Crow and Its Afterlives (2022); and Class Notes: Posing As Politics and Other Thoughts on the American Scene (2000).

The recent New York Times op-ed by N. Gregory Mankiw, "Three Reasons for Those Hefty College Tuition Bills," is pure ideological huffing and puffing of the sort we'd expect from a former chair of George W. Bush's Council of Economic Advisors. It's just a bushel of the same old free-market shibboleths typically invoked to dismiss out of hand any position that doesn't comport with the market fundamentalist perspective on the world.

First, although this point may not seem to line up directly with the argument for free public higher education, the relationship between educational attainment and income is at best more complicated than Mankiw claims, and he is in an important sense just wrong. For most workers unionization is probably a more significant determinant of income and quality of employment than is post-secondary educational attainment. The utilitarian argument that justifies pursuit of higher education as preparation for employment is faulty partly because it rests on flimflam about the economic impact of technology. Technological innovation is at least as likely to deskill--to produce low-skill, low-wage jobs--as it is to generate new higher paying jobs with greater skill requirements. (Think of commercial "innovations" like Grubhub and delivery.com, that make it possible to get a sandwich at whim any hour of day or night with minimal human contact, or Uber; the hype of technosavvy convenience conceals the reality that what makes those services work effectively is highly exploited labor.)

"Sanders has made clear that access to higher education should be available to all, so far as interest and demonstrated performance can take them, as a right - without regard to ability to pay."

Indeed, the technological innovations in higher education that Mankiw mentions are primarily about displacing and degrading academic labor - speeding up faculty workloads and intensifying the shift to contingent, horribly underpaid and exploited adjunct faculty positions. Even he notes that these innovations do not translate into improved teaching and learning. He observes that "the ideal experience for a student is a small class that fosters personal interaction with a dedicated instructor," which is precisely the pedagogical approach those innovations, beneath a breathless patter of technofetishism, undermine.

Moreover, the utilitarian argument fails on its own terms because, although some fields--e.g., medicine, engineering, etc.--do require specialized post-secondary education as necessary preparation for operating as a professional, very many others do not.

According to a 2012 report from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), only about 20% of jobs in the American economy require a college degree, and, technofetishism notwithstanding, that percentage is projected to increase only very marginally (to 20.5%) by 2020. To reinforce the point, the BLS report estimates that the two fastest growing job categories by percentage are "personal care aides" and "home health aides," jobs that that are classified as low-skill, requiring "less than high school" educational attainment, and are paid low wages. (It is a travesty that the labor of those workers who provide direct care for people who are chronically ill, disabled and elderly is so grievously devalued, but the key issue here is that those most rapidly growing job categories do not require college attendance, much less graduation, which indeed would probably deem an applicant "overqualified.") Moreover, even when listed as a requirement for employment, possession of a higher education credential is commonly not necessary for performance of a particular job but functions instead as an employment screen, a largely arbitrary criterion for exclusion, not unlike how race and gender have functioned historically. From that perspective, the apparent connection between possession of a higher education credential and income depends on not everyone having access to college and university study. If more people had access, a college degree would lose its effectiveness as an employment screen. This contradiction in Mankiw's contention is yet another expression of free-market ideologues' ability to see only congeries of isolated individuals and not the social aggregate.

Many advocates of expanding access to higher education, including progressives, nonetheless have found the human capital argument--that college education improves earning power--seductive because it seems to provide a practical, noncontroversial justification for the importance of college, but that argument is problematic on its merits for the reasons I've indicated. And it no longer has even the rhetorical force it once seemed to have for defending higher education as a social good. At this point the utilitarian, employment-related view of higher education is deployed much more effectively by the private, non-profit entities that reduce higher education to a bogus simulacrum of job training and stimulate a race to the bottom in the higher ed field in general. In this regard, one very important feature of Senator Bernie Sanders's College For All Act (S. 1373) is that it calls for increasing numbers and percentages of full-time faculty and improved salary and working conditions for part-time or contingent faculty. Guaranteeing access to higher education as a right means not only eliminating ability to pay as a limitation; it also must mean providing the material conditions under which high quality college and university education can occur, and those include the economic and intellectual security of faculty.

Another clear illustration of Mankiw's ideological bias is that he simply dismisses the fact that the College For All Act favors "government-run over private colleges" as a weakness. Not only are there no "government-run" colleges, except perhaps the service academies; Mankiw provides no reason for his assertion, but we can only assume that his point is that public goods are by definition inferior to those produced through private market forces. He also insists that under the College For All Act tuition wouldn't be free; its cost would only be shifted from individual students to generic taxpayers. This contention is consistent with the right-wing view that government provision of public goods and services amounts to a tyrannical imposition on individuals who should be able to choose the bundles of amenities that would satisfy their needs and desires in the private market.

Mankiw's preferred alternative underscores that bias. He rehearses the proposal long advocated by the ultra-right wing Cato Institute, now apparently touted by Marco Rubio, that funding college tuition should be entirely privatized, that prospective students should appeal to venture capitalists who would lend them money for tuition against a promise to a portion of future earnings. Such a system would further marketize higher education, making ability to finance college dependent on a venture capitalist's capricious assessment of future earning power based on little more than the prestige of the institution at which prospective students intend to matriculate and the courses of study they intend to follow.

This proposal underscores what Mankiw is either ideologically blind to or disingenuously chooses not to admit. Sen. Sanders's vision of higher education is fundamentally different from and at odds with his. Sanders has made clear that access to higher education should be available to all, so far as interest and demonstrated performance can take them, as a right - without regard to ability to pay. Mankiw mentions that Sanders proposes that access to higher education should be a right, but he does not argue with that proposition or even discuss its implications. He simply responds with assertions scooped from the grab bag of free-market bromides. Either way, Mankiw's tack is unfortunate. It could be useful to have an open discussion of the different visions of the good society from which Sanders' and his approaches to improving access to higher education emerge. Instead, Mankiw concludes with the stale canard, the classic academic's obfuscation that "there are no easy answers here." He's wrong; the answers to how to address the intensifying crisis in access to higher education are almost laughably easy, and are laid out clearly in Sanders' College For All Act. It would have been interesting had Prof. Mankiw been of a mind to debate it on its merits because this is a moment that calls out in a particularly sharp way for debate over fundamental visions of how the society should be governed, which values and interests should take priority in American political life. Assessing the different approaches to interpreting and addressing the deepening crisis in access to higher provides a clear view of the contending values and priorities that face us.

"At this juncture in American politics we need to assert a political vision unequivocally animated by the spirit in FDR's Second Bill of Rights."

Prof. Mankiw sees market rationality as the only defensible social ideal. He opposes the notion that government has a responsibility for protecting and enhancing the social welfare. This is the ideal of capitalist predators, which reigned absolutely in this country until the social insurgencies of the last two-thirds of the twentieth century won protections for working people that were institutionalized as law and social policy. The fruit of those victories have been under relentless attack for nearly forty years now. That attack has been increasingly bipartisan, as both Clinton and Obama administrations have retreated from the conviction exemplified in Franklin Delano Roosevelt's Second Bill of Rights, which could be enforced and sustained only by government. These included:

- The right to a useful and remunerative job in the industries or shops or farms or mines of the nation;

- The right to earn enough to provide adequate food and clothing and recreation;

- The right of every farmer to raise and sell his products at a return which will give him and his family a decent living;

- The right of every businessman, large and small, to trade in an atmosphere of freedom from unfair competition and domination by monopolies at home or abroad;

- The right of every family to a decent home;

- The right to adequate medical care and the opportunity to achieve and enjoy good health;

- The right to adequate protection from the economic fears of old age, sickness, accident, and unemployment;

- The right to a good education.

All of these rights spell security. And after this war is won we must be prepared to move forward, in the implementation of these rights, to new goals of human happiness and well-being.

"After this war is won we must be prepared to move forward, in the implementation of these rights, to new goals of human happiness and well-being."

At this juncture in American politics we need to assert a political vision unequivocally animated by the spirit in FDR's Second Bill of Rights. It is time for us to demand an agenda that proceeds from a concrete sense of what the country would look like, what the thrust of public policy would be, if the interests and real, felt concerns of the vast majority of working and middle-class people were the central priority of our national government. Senator Sanders's campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination has put that possibility in the public spotlight. I can attest to that personally. After having spent nearly fifteen years agitating for free public higher education as a political objective, I've found it more than exciting to see that the campaign has put the issue, through the College For All Act, on the table for national discussion.

The Sanders campaign has the potential to do much more to shift the terms of political debate from privileging Wall Street's interests to focus on those of working people - among other things, to galvanize public support for postal banking and full commitment to funding the United States Postal Service, to fight for real national health care on a single-payer model, to undo erroneously named "trade" agreements that are really about strengthening corporate power and driving down workers' living standards here and elsewhere, to address the environmental crisis in a serious way, to push for massive increases in public investment to stimulate real full employment and to rebuild crumbling social and physical infrastructure, and to eliminate the hideous disgrace of mass incarceration and the terroristic forms of neoliberal policing associated with it. Only the Sanders campaign embraces those objectives forcefully and on principle, and only the Sanders campaign has the capacity to build the sort of broadly based working and middle class alliance--on the basis of frank appeal to common interests across all the other seeming bases of division--essential for this program to become a reality.The other side is aware of this potential and therefore its minions like Mankiw are stepping up attacks.

Is it possible to build a popular movement strong and serious enough to withstand those attacks, whether they come from Republicans or other Democrats? I believe it is, but only if we work for it.