Climate Apocalypse and/or Democracy

In the last week, a group of scientists and a prominent historian each predicted a climate apocalypse. The scientists, led by Ricarda Winkelmann of Germany's Potsdam University, issued a paper finding that, if humans burn the rest of the world's estimated fossil fuel reserves -- which might take only another 140 years at current rates of increase -- effectively all of the world's ice will melt, and sea levels will rise some 160 feet, enough to change the surface of the planet and drown, among others, New York, London, Shanghai, Buenos Aires, Tokyo, and all of Bangladesh.

Historian Timothy Snyder of Yale argued in the New York Times that climate change may bring us the next Hitler. If we ignore the warnings of science and don't start investing in clean technologies, climate shocks will push countries into panic-inducing scarcity, inspiring everything from ethnic and religious conflict in Africa and the Middle East to imperial land grabs by a hungry and worried China. The Nazi precedent is at the heart of Snyder's essay, which is titled "The Next Genocide." For him, Hitler's genocidal war for "lebensraum," or "living space" for Germans, is a paradigm of an anti-scientific response to an ecological crisis. Snyder emphasizes that Hitler rejected scientific measures to increase crop yields and called for Germans to colonize Ukraine and the rest of Europe's grain belt as protection against a food-poor future.

Taken together, these two warnings underscore the discomforting fact that the future of the planet is a political problem. The map of every coastline, the habitability or uninhabitability of the places where billions of people live today, will arise from policy decisions, as surely as if we were detonating those cities, or literally playing God and raising the seas with a word. This is only an especially vivid example of the new human condition, the Anthropocene, in which people are a geological force shaping the Earth. From now on, the world we inhabit will be the one we have made. We can't decide to stop shaping the planet, but only what shape to give it. And the only way to decide deliberately and explicitly is through politics. Nothing else can bind and direct us in the right way.

And, as Snyder emphasizes, ecological crisis can make politics horrible. It can power the worst politics imaginable, to the point of genocide. But avoiding that awful future isn't just a matter of accepting scientific guidance and opposing evil where it arises.

Instead, we can ask what kind of politics makes ecological crises less terrible. Amartya Sen, the 1998 Nobel laureate in economics, famously observed that no famine has ever taken place in a democracy. That is, a natural disaster isn't simply a matter of drought or crop failure; it is a joint product of these events and political decisions: who gets the food, whether to let people starve. No democracy has let its own people starve -- which is an abstract way of saying that democratic citizens have not let one another starve, or, more muscularly, have refused to be starved. There is a key here to a politics for the Anthropocene: a world of ecological crisis, where ecology is both a political problem and a political creation, must be democratic, or else it will be terrible.

Unfortunately, saying this states a problem more than a solution. Is there any easy, or even attractive, way to translate democracy to the global level? Not really. And isn't it democracy -- admittedly a faltering version -- that's giving so much airtime to climate deniers in the US? Yes. What a mess. It isn't that a democratic Anthropocene is a nice idea. It's just that its slim chance is better than any alternative.

Democracy is the only way we have to take responsibility for a common world while recognizing that every person is a partner in making and dwelling in the world we make together. Once you see that the planetary future is a political question, what alternative is there? German technocrats may be able to hold down Greece, but it will take democratic self-restraint to discipline energy use in the United States. No global monarchy, green or otherwise, is on the way. We may not be the people we have been waiting for, as Barack Obama used to say we were; but no one else is coming.

One of the most telling points in Snyder's essay is that the worst eco-politics isn't necessarily a response to scarcity: it can just as easily be driven by greed. Hitler's lebensraum was a bid for a thousand fat-and-happy years; Snyder quotes Nazi propagandist Joseph Goebbels as promising "a big breakfast, a big lunch, and a big dinner." Future Chinese governments are leasing land in Africa and Ukraine, not just to avoid starvation, but because their legitimacy depends on a rising standard of living. There is no finish line for a regime that rests on that basis: failing economic growth would bring down a government from Washington to Berlin to Moscow to Beijing. We produce political legitimacy by placating greed, at great and growing cost to the future.

So another way that a livable Anthropocene future would have to be democratic is this: a people would have to accept, willingly, limits on the demands they make on the natural world. They would have to accept that they have enough.

Greed is the other side of fear; sufficiency is much easier to find if you are unafraid. An economy that guarantees some measure of security and dignity to everyone will be that much more likely to cultivate the power to stop, take a breath, and stop insisting on more.

A world where people accept a common fate and try to shape it together as equals; economies that do not make people afraid. Neither of these, alas, seems to be the leading trend. But there are hints of both. The growing movement to address climate change -- from fossil-fuel divestment campaigns to kayakers blocking tankers carrying tar-sands oil -- is a try at building international political ties bonds for a global problem. These movements may be a precursor to an international democratic effort to take joint responsibility for the planet.

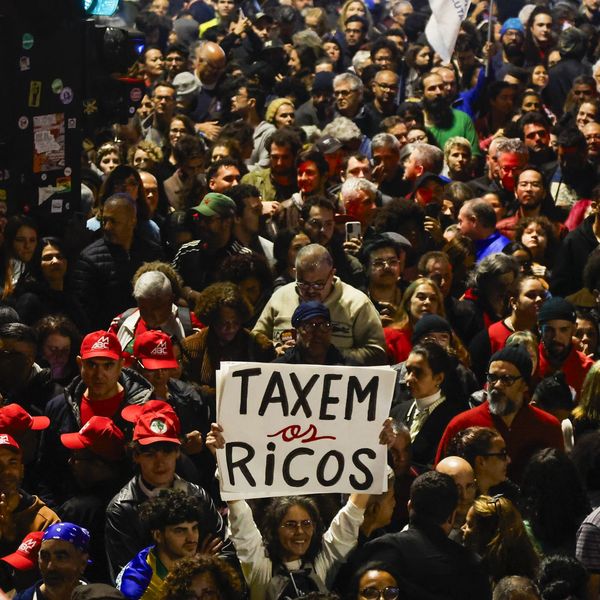

The new political concern with inequality and insecurity, which runs from Bernie Sanders's unexpected strength in the US and Jeremy Corbyn's surprise victory as head of Britain's Labor Party to the rise of anti-austerity parties in Greece and Spain, shows a determination to build a social world that is less harsh and frightening. We need both of these -- the new climate movements and the new search for shared economic security -- to have a fighting chance at a workable democratic Anthropocene.

According to Ricarda Winkelmann's climate scientists, we have less than 150 years. That is a lot longer than the time between the first meetings of abolitionist societies in England and the end of chattel slavery in the British Empire and the United States. New moral and political visions really can help people to change what is possible. This is especially true when those visions are both horrible and inspiring, helping to show the violence of how we are living and the dignity and hope in overcoming it.

That 150 years is also less than a blink in the eye of planetary time. And that eye is now a human one, looking back at us from a future that only we will make.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

In the last week, a group of scientists and a prominent historian each predicted a climate apocalypse. The scientists, led by Ricarda Winkelmann of Germany's Potsdam University, issued a paper finding that, if humans burn the rest of the world's estimated fossil fuel reserves -- which might take only another 140 years at current rates of increase -- effectively all of the world's ice will melt, and sea levels will rise some 160 feet, enough to change the surface of the planet and drown, among others, New York, London, Shanghai, Buenos Aires, Tokyo, and all of Bangladesh.

Historian Timothy Snyder of Yale argued in the New York Times that climate change may bring us the next Hitler. If we ignore the warnings of science and don't start investing in clean technologies, climate shocks will push countries into panic-inducing scarcity, inspiring everything from ethnic and religious conflict in Africa and the Middle East to imperial land grabs by a hungry and worried China. The Nazi precedent is at the heart of Snyder's essay, which is titled "The Next Genocide." For him, Hitler's genocidal war for "lebensraum," or "living space" for Germans, is a paradigm of an anti-scientific response to an ecological crisis. Snyder emphasizes that Hitler rejected scientific measures to increase crop yields and called for Germans to colonize Ukraine and the rest of Europe's grain belt as protection against a food-poor future.

Taken together, these two warnings underscore the discomforting fact that the future of the planet is a political problem. The map of every coastline, the habitability or uninhabitability of the places where billions of people live today, will arise from policy decisions, as surely as if we were detonating those cities, or literally playing God and raising the seas with a word. This is only an especially vivid example of the new human condition, the Anthropocene, in which people are a geological force shaping the Earth. From now on, the world we inhabit will be the one we have made. We can't decide to stop shaping the planet, but only what shape to give it. And the only way to decide deliberately and explicitly is through politics. Nothing else can bind and direct us in the right way.

And, as Snyder emphasizes, ecological crisis can make politics horrible. It can power the worst politics imaginable, to the point of genocide. But avoiding that awful future isn't just a matter of accepting scientific guidance and opposing evil where it arises.

Instead, we can ask what kind of politics makes ecological crises less terrible. Amartya Sen, the 1998 Nobel laureate in economics, famously observed that no famine has ever taken place in a democracy. That is, a natural disaster isn't simply a matter of drought or crop failure; it is a joint product of these events and political decisions: who gets the food, whether to let people starve. No democracy has let its own people starve -- which is an abstract way of saying that democratic citizens have not let one another starve, or, more muscularly, have refused to be starved. There is a key here to a politics for the Anthropocene: a world of ecological crisis, where ecology is both a political problem and a political creation, must be democratic, or else it will be terrible.

Unfortunately, saying this states a problem more than a solution. Is there any easy, or even attractive, way to translate democracy to the global level? Not really. And isn't it democracy -- admittedly a faltering version -- that's giving so much airtime to climate deniers in the US? Yes. What a mess. It isn't that a democratic Anthropocene is a nice idea. It's just that its slim chance is better than any alternative.

Democracy is the only way we have to take responsibility for a common world while recognizing that every person is a partner in making and dwelling in the world we make together. Once you see that the planetary future is a political question, what alternative is there? German technocrats may be able to hold down Greece, but it will take democratic self-restraint to discipline energy use in the United States. No global monarchy, green or otherwise, is on the way. We may not be the people we have been waiting for, as Barack Obama used to say we were; but no one else is coming.

One of the most telling points in Snyder's essay is that the worst eco-politics isn't necessarily a response to scarcity: it can just as easily be driven by greed. Hitler's lebensraum was a bid for a thousand fat-and-happy years; Snyder quotes Nazi propagandist Joseph Goebbels as promising "a big breakfast, a big lunch, and a big dinner." Future Chinese governments are leasing land in Africa and Ukraine, not just to avoid starvation, but because their legitimacy depends on a rising standard of living. There is no finish line for a regime that rests on that basis: failing economic growth would bring down a government from Washington to Berlin to Moscow to Beijing. We produce political legitimacy by placating greed, at great and growing cost to the future.

So another way that a livable Anthropocene future would have to be democratic is this: a people would have to accept, willingly, limits on the demands they make on the natural world. They would have to accept that they have enough.

Greed is the other side of fear; sufficiency is much easier to find if you are unafraid. An economy that guarantees some measure of security and dignity to everyone will be that much more likely to cultivate the power to stop, take a breath, and stop insisting on more.

A world where people accept a common fate and try to shape it together as equals; economies that do not make people afraid. Neither of these, alas, seems to be the leading trend. But there are hints of both. The growing movement to address climate change -- from fossil-fuel divestment campaigns to kayakers blocking tankers carrying tar-sands oil -- is a try at building international political ties bonds for a global problem. These movements may be a precursor to an international democratic effort to take joint responsibility for the planet.

The new political concern with inequality and insecurity, which runs from Bernie Sanders's unexpected strength in the US and Jeremy Corbyn's surprise victory as head of Britain's Labor Party to the rise of anti-austerity parties in Greece and Spain, shows a determination to build a social world that is less harsh and frightening. We need both of these -- the new climate movements and the new search for shared economic security -- to have a fighting chance at a workable democratic Anthropocene.

According to Ricarda Winkelmann's climate scientists, we have less than 150 years. That is a lot longer than the time between the first meetings of abolitionist societies in England and the end of chattel slavery in the British Empire and the United States. New moral and political visions really can help people to change what is possible. This is especially true when those visions are both horrible and inspiring, helping to show the violence of how we are living and the dignity and hope in overcoming it.

That 150 years is also less than a blink in the eye of planetary time. And that eye is now a human one, looking back at us from a future that only we will make.

In the last week, a group of scientists and a prominent historian each predicted a climate apocalypse. The scientists, led by Ricarda Winkelmann of Germany's Potsdam University, issued a paper finding that, if humans burn the rest of the world's estimated fossil fuel reserves -- which might take only another 140 years at current rates of increase -- effectively all of the world's ice will melt, and sea levels will rise some 160 feet, enough to change the surface of the planet and drown, among others, New York, London, Shanghai, Buenos Aires, Tokyo, and all of Bangladesh.

Historian Timothy Snyder of Yale argued in the New York Times that climate change may bring us the next Hitler. If we ignore the warnings of science and don't start investing in clean technologies, climate shocks will push countries into panic-inducing scarcity, inspiring everything from ethnic and religious conflict in Africa and the Middle East to imperial land grabs by a hungry and worried China. The Nazi precedent is at the heart of Snyder's essay, which is titled "The Next Genocide." For him, Hitler's genocidal war for "lebensraum," or "living space" for Germans, is a paradigm of an anti-scientific response to an ecological crisis. Snyder emphasizes that Hitler rejected scientific measures to increase crop yields and called for Germans to colonize Ukraine and the rest of Europe's grain belt as protection against a food-poor future.

Taken together, these two warnings underscore the discomforting fact that the future of the planet is a political problem. The map of every coastline, the habitability or uninhabitability of the places where billions of people live today, will arise from policy decisions, as surely as if we were detonating those cities, or literally playing God and raising the seas with a word. This is only an especially vivid example of the new human condition, the Anthropocene, in which people are a geological force shaping the Earth. From now on, the world we inhabit will be the one we have made. We can't decide to stop shaping the planet, but only what shape to give it. And the only way to decide deliberately and explicitly is through politics. Nothing else can bind and direct us in the right way.

And, as Snyder emphasizes, ecological crisis can make politics horrible. It can power the worst politics imaginable, to the point of genocide. But avoiding that awful future isn't just a matter of accepting scientific guidance and opposing evil where it arises.

Instead, we can ask what kind of politics makes ecological crises less terrible. Amartya Sen, the 1998 Nobel laureate in economics, famously observed that no famine has ever taken place in a democracy. That is, a natural disaster isn't simply a matter of drought or crop failure; it is a joint product of these events and political decisions: who gets the food, whether to let people starve. No democracy has let its own people starve -- which is an abstract way of saying that democratic citizens have not let one another starve, or, more muscularly, have refused to be starved. There is a key here to a politics for the Anthropocene: a world of ecological crisis, where ecology is both a political problem and a political creation, must be democratic, or else it will be terrible.

Unfortunately, saying this states a problem more than a solution. Is there any easy, or even attractive, way to translate democracy to the global level? Not really. And isn't it democracy -- admittedly a faltering version -- that's giving so much airtime to climate deniers in the US? Yes. What a mess. It isn't that a democratic Anthropocene is a nice idea. It's just that its slim chance is better than any alternative.

Democracy is the only way we have to take responsibility for a common world while recognizing that every person is a partner in making and dwelling in the world we make together. Once you see that the planetary future is a political question, what alternative is there? German technocrats may be able to hold down Greece, but it will take democratic self-restraint to discipline energy use in the United States. No global monarchy, green or otherwise, is on the way. We may not be the people we have been waiting for, as Barack Obama used to say we were; but no one else is coming.

One of the most telling points in Snyder's essay is that the worst eco-politics isn't necessarily a response to scarcity: it can just as easily be driven by greed. Hitler's lebensraum was a bid for a thousand fat-and-happy years; Snyder quotes Nazi propagandist Joseph Goebbels as promising "a big breakfast, a big lunch, and a big dinner." Future Chinese governments are leasing land in Africa and Ukraine, not just to avoid starvation, but because their legitimacy depends on a rising standard of living. There is no finish line for a regime that rests on that basis: failing economic growth would bring down a government from Washington to Berlin to Moscow to Beijing. We produce political legitimacy by placating greed, at great and growing cost to the future.

So another way that a livable Anthropocene future would have to be democratic is this: a people would have to accept, willingly, limits on the demands they make on the natural world. They would have to accept that they have enough.

Greed is the other side of fear; sufficiency is much easier to find if you are unafraid. An economy that guarantees some measure of security and dignity to everyone will be that much more likely to cultivate the power to stop, take a breath, and stop insisting on more.

A world where people accept a common fate and try to shape it together as equals; economies that do not make people afraid. Neither of these, alas, seems to be the leading trend. But there are hints of both. The growing movement to address climate change -- from fossil-fuel divestment campaigns to kayakers blocking tankers carrying tar-sands oil -- is a try at building international political ties bonds for a global problem. These movements may be a precursor to an international democratic effort to take joint responsibility for the planet.

The new political concern with inequality and insecurity, which runs from Bernie Sanders's unexpected strength in the US and Jeremy Corbyn's surprise victory as head of Britain's Labor Party to the rise of anti-austerity parties in Greece and Spain, shows a determination to build a social world that is less harsh and frightening. We need both of these -- the new climate movements and the new search for shared economic security -- to have a fighting chance at a workable democratic Anthropocene.

According to Ricarda Winkelmann's climate scientists, we have less than 150 years. That is a lot longer than the time between the first meetings of abolitionist societies in England and the end of chattel slavery in the British Empire and the United States. New moral and political visions really can help people to change what is possible. This is especially true when those visions are both horrible and inspiring, helping to show the violence of how we are living and the dignity and hope in overcoming it.

That 150 years is also less than a blink in the eye of planetary time. And that eye is now a human one, looking back at us from a future that only we will make.