SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

How many times have we heard it?

" Organic food is great for those who can afford it, but not an option for most of us."

This simplistic adage is applied to most proposals that question the cheap, processed food that is the cornerstone of this country's epidemic of diet-related diseases. Arguing in favor of organic, a movable feast of foodies tells us that we simply have to learn to pay more if we want to eat local, organic, sustainably- produced food. In the United States that leaves at least 49 million food insecure people (and much of the middle class) out of luck.

Sorry, no healthy food for you.

No one seems to ask why we need cheap food in the first place. The simple answer is that cheap food helps to keep wages down. This is especially important when a country is industrializing and needs low-paid but amply-fed workers. Later, cheap food helps free up expendable income to buy the consumer goods produced by all that industrialization. These were supposed to be stages of economic development, to be surpassed as workers accumulate wealth and climb up the economic ladder. Somehow, in our current food system both poor people and cheap food became permanent fixtures -- despite the U.S. food industry's impressive economic growth.

With over 20 million workers, the food system is the largest and fastest-growing sector in the nation. Unfortunately, with a national median wage of $9.90 per hour, the vast majority of food workers toil under the poverty line. The low minimum wage especially affects food service workers who rely on tips to make a living (waiters, bussers, runners); their minimum wage is $2.13 an hour. When totaled up, that amounts to justfor a full-time worker. There is a clear problem with this unlivable wage for food service workers, yet some still argue against increasing the minimum wage.

The central argument of opponents is that an increase in the minimum wage would result in an increase of prices for basic goods, and, as a result, would not end up helping the very low-wage workers whom the minimum wage increase is designed to help. A studydone by the Food Labor Research Center at the University of California, Berkeley looked at the impact of the minimum wage on the price of food. The study found that while the bill to raise the minimum wage, the Fair Minimum Wage Act, would provide a 33 percent wage increase for the regular worker, earnings would more than double for food service workers. As a result of these increases in wages, retail grocery store food prices would only increase by an average of less than half a percent. So what does this mean? Over the proposed three-year plan to increase the minimum wage, food prices both away and at home, would only amount to about 10 cents more per day.

America's food workers are the largest segment of the working population who desperately need an increase in the minimum wage, in order to support their families. The Food Chain Workers Alliance, a national coalition of 21 food worker organizations, is bringing awareness to this issue with International Food Workers Week during this Thanksgiving week (November 24-30) in order to educate consumers on how food gets from farms to our forks.

What out the 20 million workers in the food system need in order to buy the healthy food currently reserved for "elite" consumers is a living wage. Passing the Fair Minimum Wage Act of 2013 is a step in the right direction. Not only would this help pull us out of the current recession, it would provide a great boost to the good food movement.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

How many times have we heard it?

" Organic food is great for those who can afford it, but not an option for most of us."

This simplistic adage is applied to most proposals that question the cheap, processed food that is the cornerstone of this country's epidemic of diet-related diseases. Arguing in favor of organic, a movable feast of foodies tells us that we simply have to learn to pay more if we want to eat local, organic, sustainably- produced food. In the United States that leaves at least 49 million food insecure people (and much of the middle class) out of luck.

Sorry, no healthy food for you.

No one seems to ask why we need cheap food in the first place. The simple answer is that cheap food helps to keep wages down. This is especially important when a country is industrializing and needs low-paid but amply-fed workers. Later, cheap food helps free up expendable income to buy the consumer goods produced by all that industrialization. These were supposed to be stages of economic development, to be surpassed as workers accumulate wealth and climb up the economic ladder. Somehow, in our current food system both poor people and cheap food became permanent fixtures -- despite the U.S. food industry's impressive economic growth.

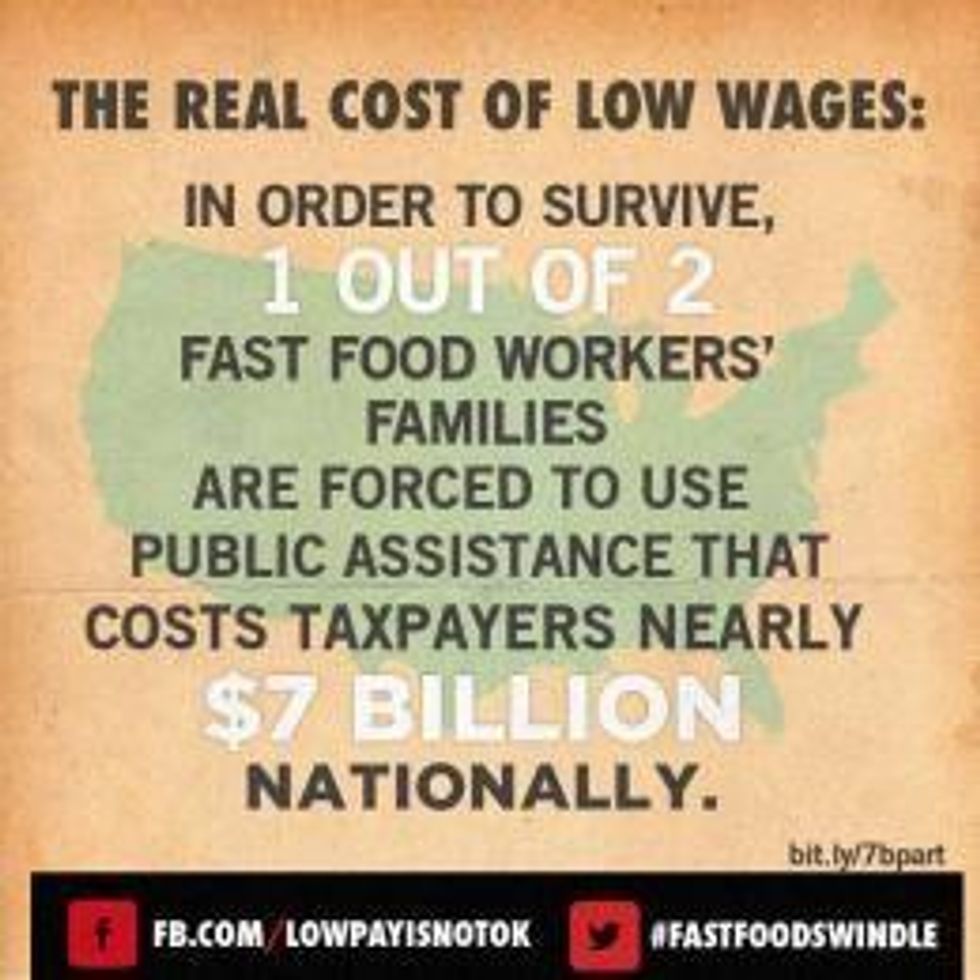

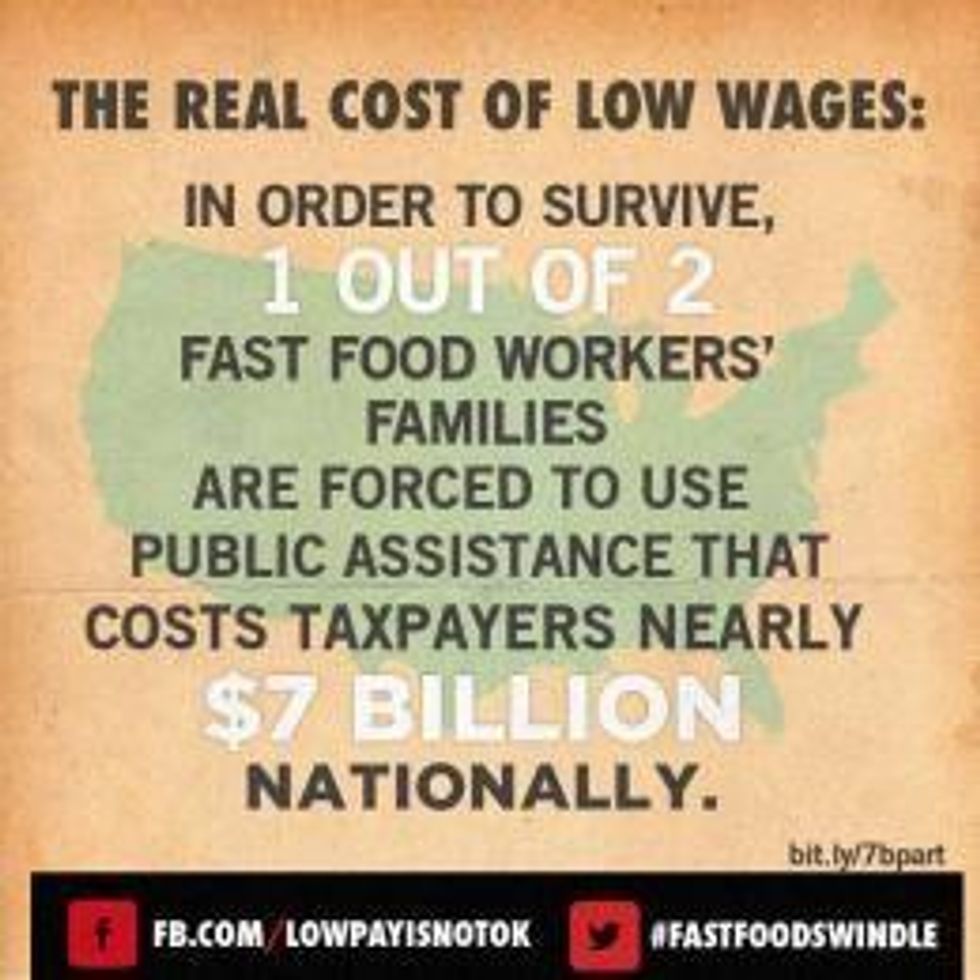

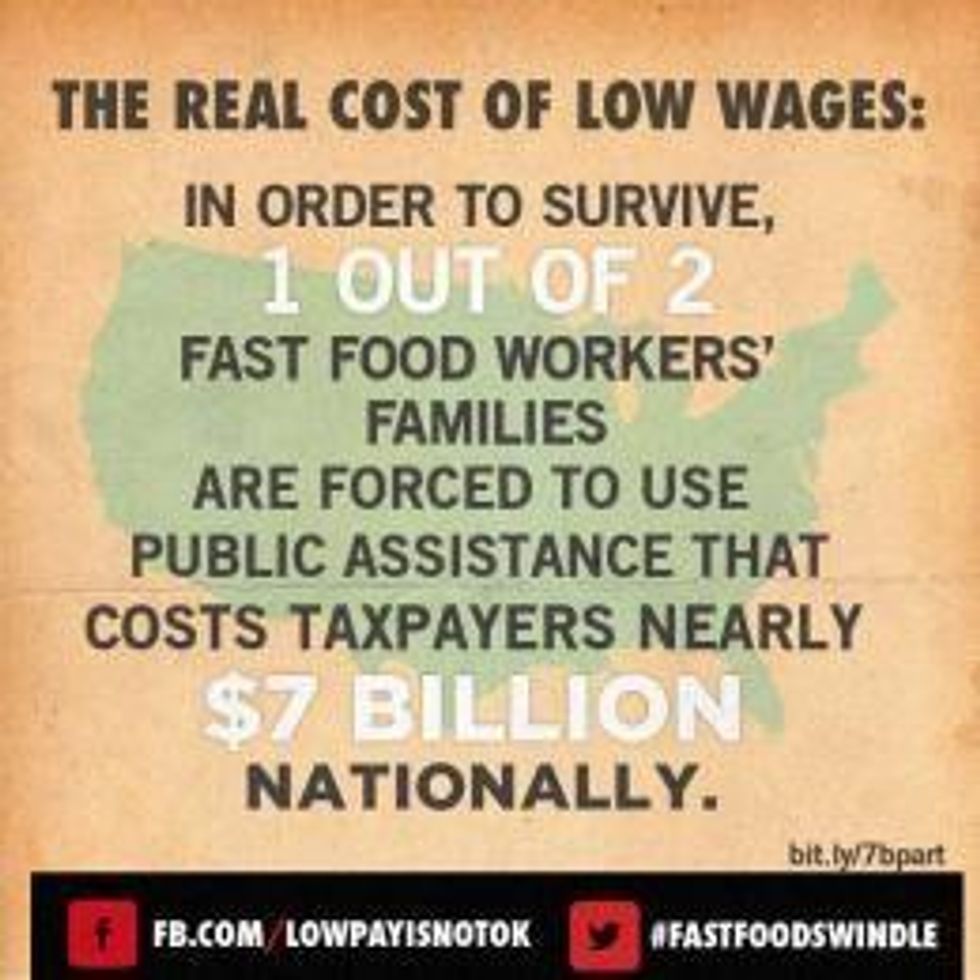

With over 20 million workers, the food system is the largest and fastest-growing sector in the nation. Unfortunately, with a national median wage of $9.90 per hour, the vast majority of food workers toil under the poverty line. The low minimum wage especially affects food service workers who rely on tips to make a living (waiters, bussers, runners); their minimum wage is $2.13 an hour. When totaled up, that amounts to justfor a full-time worker. There is a clear problem with this unlivable wage for food service workers, yet some still argue against increasing the minimum wage.

The central argument of opponents is that an increase in the minimum wage would result in an increase of prices for basic goods, and, as a result, would not end up helping the very low-wage workers whom the minimum wage increase is designed to help. A studydone by the Food Labor Research Center at the University of California, Berkeley looked at the impact of the minimum wage on the price of food. The study found that while the bill to raise the minimum wage, the Fair Minimum Wage Act, would provide a 33 percent wage increase for the regular worker, earnings would more than double for food service workers. As a result of these increases in wages, retail grocery store food prices would only increase by an average of less than half a percent. So what does this mean? Over the proposed three-year plan to increase the minimum wage, food prices both away and at home, would only amount to about 10 cents more per day.

America's food workers are the largest segment of the working population who desperately need an increase in the minimum wage, in order to support their families. The Food Chain Workers Alliance, a national coalition of 21 food worker organizations, is bringing awareness to this issue with International Food Workers Week during this Thanksgiving week (November 24-30) in order to educate consumers on how food gets from farms to our forks.

What out the 20 million workers in the food system need in order to buy the healthy food currently reserved for "elite" consumers is a living wage. Passing the Fair Minimum Wage Act of 2013 is a step in the right direction. Not only would this help pull us out of the current recession, it would provide a great boost to the good food movement.

How many times have we heard it?

" Organic food is great for those who can afford it, but not an option for most of us."

This simplistic adage is applied to most proposals that question the cheap, processed food that is the cornerstone of this country's epidemic of diet-related diseases. Arguing in favor of organic, a movable feast of foodies tells us that we simply have to learn to pay more if we want to eat local, organic, sustainably- produced food. In the United States that leaves at least 49 million food insecure people (and much of the middle class) out of luck.

Sorry, no healthy food for you.

No one seems to ask why we need cheap food in the first place. The simple answer is that cheap food helps to keep wages down. This is especially important when a country is industrializing and needs low-paid but amply-fed workers. Later, cheap food helps free up expendable income to buy the consumer goods produced by all that industrialization. These were supposed to be stages of economic development, to be surpassed as workers accumulate wealth and climb up the economic ladder. Somehow, in our current food system both poor people and cheap food became permanent fixtures -- despite the U.S. food industry's impressive economic growth.

With over 20 million workers, the food system is the largest and fastest-growing sector in the nation. Unfortunately, with a national median wage of $9.90 per hour, the vast majority of food workers toil under the poverty line. The low minimum wage especially affects food service workers who rely on tips to make a living (waiters, bussers, runners); their minimum wage is $2.13 an hour. When totaled up, that amounts to justfor a full-time worker. There is a clear problem with this unlivable wage for food service workers, yet some still argue against increasing the minimum wage.

The central argument of opponents is that an increase in the minimum wage would result in an increase of prices for basic goods, and, as a result, would not end up helping the very low-wage workers whom the minimum wage increase is designed to help. A studydone by the Food Labor Research Center at the University of California, Berkeley looked at the impact of the minimum wage on the price of food. The study found that while the bill to raise the minimum wage, the Fair Minimum Wage Act, would provide a 33 percent wage increase for the regular worker, earnings would more than double for food service workers. As a result of these increases in wages, retail grocery store food prices would only increase by an average of less than half a percent. So what does this mean? Over the proposed three-year plan to increase the minimum wage, food prices both away and at home, would only amount to about 10 cents more per day.

America's food workers are the largest segment of the working population who desperately need an increase in the minimum wage, in order to support their families. The Food Chain Workers Alliance, a national coalition of 21 food worker organizations, is bringing awareness to this issue with International Food Workers Week during this Thanksgiving week (November 24-30) in order to educate consumers on how food gets from farms to our forks.

What out the 20 million workers in the food system need in order to buy the healthy food currently reserved for "elite" consumers is a living wage. Passing the Fair Minimum Wage Act of 2013 is a step in the right direction. Not only would this help pull us out of the current recession, it would provide a great boost to the good food movement.